Introduction

The

proliferation of learning/course management systems

(L/CMS) over the past decade has occurred in

multiple sectors: K-12, higher education, government

and the business workplace. Distributed learning

systems originated within a Fordist framework

(uniform, mass produced and delivered) and

transitioned to a neo-Fordist model in the late 20th

century with more customization and innovation

(Edwards, 1995). System design and delivery

mechanisms have been historically unique across

sectors, targeting a specific audience. However, the

needs of the learners and the learning intentions of

the organization are similar across sectors, but

there has been little market overlaps among L/CMS,

although this appears to be changing. Therefore in

the lifetime of a learner, there is an implicit

expectation that a new system will be learned and

used to support educational and then workplace

learning. The authors argue that with the advent of

Web 2.0 applications and the open knowledge paradigm

(Norris, Lafrere, & Mason, 2003), the notion of

“system” as a framework for learning is now

inadequate in a post-Fordist world that provides for

flexible processes, dynamic innovation, and

authority of content by the user. A survey of

learning professionals ranking the top tools for

learning (Centre for

Learning & Performance Technologies, 2007) reveals

that only one CMS is perceived to meet the

requirements for authentic learning: Moodle™.

However, perception and applied theory can be at

odds. This study analyzes the use of primary

L/CMS used in secondary and higher education to (a)

examine the functional differences between systems

and (b) analyze the implicit learning designs

situated in functional and interface designs. This

formative analysis provides an insight into how

current systems do or not reflect a post-Fordist

perspective that we believe is situated in current

learning theory. From this the authors illustrate

how future technological frameworks can be conceived

to address learning across the life of the learner.

An often-missing component in the decision to

implement distributed learning is an evaluation of

effectiveness research to determine if the selected

technology has the ability to address institutional

goals and concerns. The literature in this area

looks at “satisfaction” in a way that does not

always address actual learning outcomes. Overall

there exists a lack of empirical studies showing

that the use of instructional technology actually

improves learning (Arbaugh, 2002; Buckley, 2002;

McClelland, 2001; McGorry, 2003; Neal, 1998).

Studies conclude that the full potential of

instructional technology is reached only by a full

transformation of the learning process, faculty

development, and institutional systems (Buckley,

2002; Jamieson, Fisher, Gilding,

Taylor, & Trevitt, 2000; Moore, 2002). The research

on the effectiveness of distributed learning

programs indicates several areas of concern:

problems with student-instructor communication, lack

of socialization both with the instructor and other

students, student engagement and interaction,

innovation in teaching, and technical difficulties

or support (McGorry, 2003; Salisbury, Pearson,

Miller, & Marett, 2002). Finally, the instructor’s

actual technological expertise (Lea, Clayton, Draude,

& Barlow, 2001; Webster & Hackley, 1997) along with

their inability to overcome interaction problems

(Berger, 1999) has been found to be important both

in an instructor’s decisions to adopt instructional

technology and in students’ satisfaction and

learning outcomes. These findings are at odds

with return on investment (ROI) arguments that

distributed education can serve large populations

without denigrating effectiveness, a trend seen in

higher education.

Technology has shifted the nature of traditional

learning and training by removing the learner from

contexts, such as school and workplace through

Internet-facilitated learning. Three primary models

have conceptualized distributed learning:

web-enhanced classroom, hybrid/blended, and 100%

online (NCAT). However, these models focus on

delivery of instruction and don’t address the

learning designs that can be offered through

distributed learning.

Taylor‘s framework (2001) describes the shift

in distributed learning from linear and print-based

to flexible and modular/digital based:

-

The “correspondence model” relies on print-based

resources.

-

The “multimedia model” provides learning resources

through a variety of media including print.

-

The “tele-learning model” incorporates modes of

presentation of materials to include audio or

video-conferencing and broadcast TV or radio.

-

The “flexible learning model” requires that

students engage in interactive, online

computer-mediated resources and activities.

-

The “intelligent flexible learning model” is the

next generation model in which the learner

accesses learning processes and resources through

portals.

These models reflect the shift in learning theory

that has paralleled quickly evolving technological

systems that support distributed learning, as well

as the Fordist perspectives that have evolved over

the past century.

Fordism, neo-Fordism, Post-Fordism

It

is the authors’ contention that current L/CMS have

been conceptualized, designed, and utilized at the

enterprise level to reflect late 20th and

early 21st century models of

industrialization that can be compared to similar

thinking about teaching and learning. As current

learning theory indicates a need for pedagogical

approaches that support individualized, constructive

learning so are the frameworks of distance education

shifting from centralized one-size-fits all

productions of learning to personalized and

customized learning experiences, so has learning

theory.

Simonson, Smaldino, Albright, and Zvacek (2003) put

forth that although there is no consensus that

distance education in the 21st century is

appropriately framed within a production model,

there is evidence that this a viable and accurate

interpretation. Derived from economic and industrial

sociology, the three Fordist models have been used

to explain and describe how distance education has

come to be designed and delivered. Simonson, et al,

note that there was much debate about the

industrialization of distance education in the

mid-1990’s (see Zanoni &

Janssens, 2005) that has seemingly quieted in

this century.

Fordism suggests a “fully centralized, single-mode,

national distance education provider, gaining

greater economies of scale by offering courses to a

mass market, thereby justifying a greater investment

in more expensive course materials” (Simonson, et

al, 2003, p. 49). Such an approach is characterized

by a high degree of administrative control and a

clear division of work as the system is successful

due to the efficient reproduction of each area of

teaching and learning. Organizations that deliver

the same instruction via identical modalities to

varied audiences fit this model characterized by

uniformity, consistency, and separation of

instructional design from the instructor. Thus mass

produced courses are handed over to the teacher who

then acts only as a presenter. This model has worked

well for the military and large corporate training

where the values of uniformity and consistency are

critical to the mission and goals of the

organization. This is the TV dinner view of

distance education.

Neo-Fordism differs from Fordism in that it allows “

much higher levels of flexibility and diversity, and

by combining low volumes with high levels of product

and process innovation”

(Simonson, et al, 2003, p. 49). Neo-Fordism still

relies on mass production in a centralized approach

with specific divisions of production and labor.

Organizations that provide centralized mechanisms of

delivery and curriculum fit this approach while

allowing localized control at some level, be it

administrative, managerial, or instructive. This

model has worked well for for-profit producers and

delivers of distance education where consistency is

important, but uniformity is less important that

meeting specific needs – disciplinary, geographic,

professional, etc. This is the cafeteria view of

distance education.

It

is important to note that both Fordism and neo-Fordism

focus on mass production and limit control and input

from those who are actually engaged in teaching and

learning. Post-Fordism involves “high levels

of product innovation, process variability, and

labor responsibility” (p. 50), thereby focusing on a

skilled pool of workers working within a

decentralized community operating to adapt and

adjust to the needs of the learner. This approach is

probably most represented in institutional or

individual efforts of a department or program where

oversight is minimal and revisions and alternatives

can readily applied given the small populations

served. This reflects the corner bistro model of

distance education.

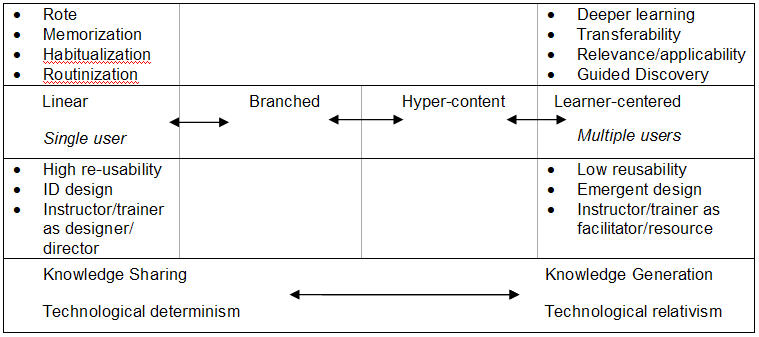

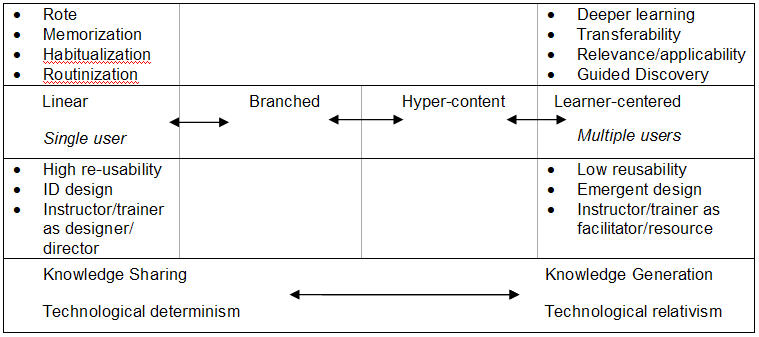

The

three perspectives indicate a continuum of teacher

vs. learner-centered instructional experiences as

noted in Figure 1.

Figure

1. Learning Designs in Distributed Learning Systems

(Diaz & McGee, 2005)

The

focus of this study is on a system. Although

post-Fordism suggests that systems are not a

complete solution to distributed learning, and

indeed there is evidence that user-centric tools are

more appropriate supports for distributed learning,

the L/CMS is now the primary mechanism for delivery

of instruction. Given these three perspectives, we

can ask the following question about L/CMS: How do

the top five L/CMS used in secondary and higher

education reflect current learning theory that is

situated in Fordist models of course delivery?

Learning Theory and distributed technology:

Secondary education

The coupling of two trends in secondary education is

creating new learning environments for millennial

learners.

First, the development of networked information

communication technologies has enabled the emergence

of distributed learning or “virtual high schools.”

Second, instructional design in these programs tends

to emphasize constructivist philosophies where

students take charge of their learning and construct

their understanding of content. Proponents of

distributed learning argue that online pedagogies

should be grounded in constructivist perspectives

(Bonk & Cunningham, 1998; Jonassen, 2000).

Although online distance education has been more prevalent in

higher education and business, virtual learning

environments are emerging as an option in secondary

education. Two dozen states have already created

state-run virtual high schools (Tucker, 2007).

Nationwide, approximately 700,000 students were

enrolled in virtual schooling in the 2005-2006

school year (Picciano & Seaman, 2007). Moreover, new

high school graduation requirements in

Michigan mandate the class of 2011 to complete an

online learning experience as part of graduation

requirements (Moser, 2006).

Constructivism is a theoretical framework that has gained

standing in secondary education in the late 20th

century (Flynn, 2004; Westerberg, 2007; Foote,

Vermette, & Battaglia, 2001). Cambre and Hawkes

(2004) assert that constructivism creates a shift in

instructional design from “standardization to

customization” (p. 50). According to Adams and Burns

(1999),

...constructivism is characterized by the following

principles: (a) learners bring their personal prior

knowledge and experiences to the learning situation;

(b) learning is internally controlled and mediated;

(c) tools, resources, experiences, and contexts help

in the construction of knowledge in multiple ways;

(d) learning occurs through a process of

accommodation and assimilation when old mental

models are challenged to create new ones; (e)

learning is an active and reflective process; and

(f) social interaction provides multiple

perspectives to create knowledge. Key components of

constructivist-compatible online learning

environments include: a)

active learning, b) authentic instructional tasks,

c)collaboration among students, and d) diverse and

multiple learning formats (Partlow & Gibbs, 2003).

The evolution

of course management systems over time has resulted

in systems with the capacity to create dynamic

online learning communities in secondary education

based on constructivist learning theories. Although

constructivism is based on a broad range of theory,

the emphasis is on the learner actively building

knowledge and meaning from their experiences.

Doolittle (1999) posits eight principles of

constructivist pedagogy necessary for learners to

constructing knowledge in online education:

1.

Learning should take place in authentic and

real-world environments

2.

Learning should involve social negotiation and

mediation.

3.

Content and skills should be made relevant to the

learner.

4.

Content and skills should be understood within the

framework of the learner's prior knowledge.

5.

Students should be assessed formatively, serving to

inform future learning experiences.

6.

Students should be encouraged to become

self-regulatory, self-mediated, and self-aware.

7.

Teachers serve primarily as guides and facilitators

of learning, not instructors.

8.

Teachers should provide for and encourage multiple

perspectives and representations of content.

Doolittle’s analysis of these principles in online

contexts concludes that it is not is not whether or

not the potential for implementing constructivism in

online education exists, but rather, whether or not

the potential will be actualized. Table 1

illustrates how constructivist principles apply to

L/CMS and Fordist perspectives.

Learning Theory and distributed technology: Higher

education

In

the 21st century our ability to anytime

access information and people allows us to learn

informally without traditional structures (Lankshear

& Knobel, 2003). We have seen changes in tools, ways

of thinking about knowledge, the learner, and how we

view learning and knowing. Technology also allows us

to locate, save, locate again, and share information

in ways that have not previously been possible (Rennie

& Mason, 2004). Given that we can learn when we want

or need, in ways that are most comfortable and

suitable, we find that learning is increasingly

initiated and organized by the learner through

discovery and self-construction. Many have argued

that how the system is designed influences how the

system is used (Johnson, 2000; Kersten, Kersten, &

Rakowski, 2002). Ullman

and Rabinowitz

(2004) argue that systems have been designed to

supplement or manage instruction and that this

structures use.

Table 1 Secondary Education: Constructivism.

|

Constructivist Principle |

Description |

Application in L/CMS |

Fordist |

|

1.

Learning should take place in real

world environments |

L/CMS must provide “complex, culturally

relevant, ill-structured domains within which

the user can operate and “live” (Doolittle,

1999, p. |

Simulations, role play, manipulation of real

world data. Team work areas that replicate

authentic places with ICT, storage, sharing and

exchange, note taking |

Post Fordist |

|

2.

Learning should involve social

negotiation and mediation. |

Learners and instructors interact, react, and reflect upon

there actions, thinking, decisions, and

positions. |

Asynchronous and synchronous communication tools: chat,

discussion, IM, blogs, wikis, whiteboards, etc.;

peer critique and annotation functions |

Post Fordist |

|

3.

Content and skills should be made

relevant to the learner |

L/CMS makes “vast amounts of very diverse

information, knowledge, and skills available to

the learner….learner is able to self-select a

relevant topic, process, or skill (Doolittle,

1999) |

L/CMS should support the teacher in providing

multiple paths for the learner to take.

Functions that provide choices in assignment

products, intelligent agent that remember

choices and progress. |

Post Fordist |

|

4.

Content and skills

should be understood within the framework of the

learner’s prior knowledge. |

L/CMS probes student understanding of topic at

the beginning of instruction and adapts

presentation of content and skills to student

understandings. |

Intelligent agent that responds to choices,

decisions, and previous interactions; pre-post

test attached to assignments. |

Post Fordist |

|

5.

Students should be assessed

formatively. |

Periodic, learner and instructor initiated

assessments and benchmarks. |

“Self-check” quizzes that assess students

during various parts of instruction and inform

student about progress. |

Post Fordist

Neo-Fordism |

|

6.

Students should be encouraged to become self

regulatory, self-mediated, and self-aware. |

Students know where they are in accomplishing

established learning outcomes. |

Learner can evaluate their work in relation to

others through anonymous reporting of class

progress by individual; timelines and deadlines

countdown and appear in multiple areas. |

Post Fordist

|

|

7.

Teachers serve primarily as guides and

facilitators of learning not instructors. |

Learners make decisions and control their

environment with an ability to go beyond or in a

different direction than a prescribed path. |

Alter interface, bookmark, annotate, create new

knowledge objects. Self-pacing, open entry open

exit modules; intelligent agents remind, prod,

and support |

Post Fordist

|

|

8.

Teachers should provide for and encourage

multiple perspectives and representations of

content. |

Focus on diverse perspectives and ways of

interacting in the world. |

Guest accounts, |

Post Fordist |

Siemens (2004) proposes a new theory of learning

that is specific to the information age. He

stipulates that chaos has become a norm for the 21st

century adult worker and learner – making sense of

the volumes of information available requires

reliable and connected networks that assist us in

determining patterns of the information that often

overwhelms us. Through self-organized networks,

Siemens puts forth, the 21st century

learner allows us to question, explore, validate,

and construct knowledge in new ways. In this way the

learner can better determine what is important and

what is unimportant. The principles of connectivism

and their application in L/CMS are illustrated in

Table 2.

Table 2 Higher Education: Connectivism

|

Connectivist Principle |

Application in L/CMS |

Fordist |

|

1.

Learning and knowledge rests in diversity of

opinions. |

Open discussion, peer critique, self-critique,

learner generation of products, publication

internal and external to system. |

Neo-Fordism

Post-Fordism |

|

2.

Learning is a process of connecting specialized

nodes or information sources. |

Learner-generated interactions (discussion,

chat, whiteboard, etc), learner-centered social

network/resources/community. |

Post-Fordism |

|

3.

Learning may reside in non-human appliances. |

Learner and instructor linkage to external

personal services (e.g. blog, wiki, social

network, photos, video, etc.); ePortfolio |

Fordism

Neo-Fordism

Post-Fordism |

|

4.

Capacity to know more is more critical than what

is currently known. |

Self-evaluation and critique; developmental

assessment (e.g. against standards, prior

learning, etc.); ePortfolio |

Neo-Fordism

Post-Fordism |

|

5.

Nurturing and maintaining connections is needed

to facilitate continual learning. |

Email can be controlled through the L/CMS; voice

mail; VOIP; assignment notes and annotations;

assessment feedback; |

Fordism

Neo-Fordism

Post-Fordism |

|

6.

Ability to see connections between fields,

ideas, and concepts is a core skill. |

Visual mapping; bookmarking; instructor and

learner self-customization of content; learner

generated glossary; learner generated objects |

Neo-Fordism

Post-Fordism |

|

7.

Currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the

intent of all connectivist learning activities. |

Expert evaluation; learner publication of

objects external to system; |

Post-Fordism |

Decision-making is in itself a learning process.

Choosing what to learn and the meaning of incoming

information is seen through the lens of a shifting

reality. While there is a right answer now, it may

be wrong tomorrow due to alterations in the

information climate affecting the decision.

Therefore, a connectivist approach to learning

design must rely on internal and external

corroboration and verification, two conditions

problematic within current L/CMS that ‘close the

door’ to outsiders and deny access once the course

concludes.

Method

Given the lack of study of system functionality and

learning design, this study utilizes a descriptive

method. We argue that L/CMS

offer the same type

of fluid, observable, and hidden learning

experiences as can occur in a classroom. Rather than

examine the phenomenology of the instructor and

learner experiences in specific L/CMS delivered

classes, we focus on the system as designed to

support teaching and learning. The very focus on

‘management’ in the name reflects a conscious and

purposeful framework of learning. We draw on

conceptual frameworks to analyze the system and in

doing so declare the lens through we view these

systems. We encourage others to take other lenses

and replicate our work, to better understand the

varied designs, implementations, and experiences

enacted through L/CMS.

First, we determine the nature of an L/CMS that

relate directly to teaching and learning. In

general, L/CMS have been seen to have three high

level functions: authoring, community, and data

management, see Table 3.

Table 3: CMS

Functions and learning principles (from

Ullman & Rabinowitz, 2004)

|

|

Instructor Actions |

Learner Actions |

Learning principle |

Fordist connection |

|

Authoring/ Publishing |

Create new content; link to content, resources;

create tests and quizzes |

Read information; access course resources;

complete assessments |

Learner construction and generation |

Learners have access to identical information

and instructions |

|

Virtual community |

Present information, chat, IM, whiteboard,

discussion |

Review and discuss information |

Interaction, facilitation, feedback |

Learners are directed and managed by instructor

with possible modifications |

|

Data Management |

Grades; registration list |

Access grades; access course |

Assigned roles, Inform learner of progress |

Instructor is in charge |

However, these features don’t directly address

teaching and learning and therefore the authors

adopted interpretations of pedagogical features

articulated by the National Learning Infrastructure

Initiative (NLII). In 2003 NLII conducted a focus

session that resulted in seven clearly articulated

features of L/CMS that relate to teaching and

learning. The NLII took these features and

constituted a Next

Generation Course Management System Workgroup from

which an analysis of CMS features that support

learning was produced. We use these functions to

frame our analysis of L/CMS because of they were

vetted through consensus of experts keeping teaching

and learning in the forefront.

This study focuses on learning theory; therefore, we

are less interested in the high level abilities of

CMS functions but rather the affordances that are

possible in a system that provide both instructor

and learning options, control, and variations on

their actions within a CMS. Therefore, the authors

each drew upon their respective principles of

learning derived from constructivism and

connectivism and the NLII functional analysis to

articulate a observational tool that articulates

technology-mediated conditions best suited to

support learning according to learner ability within

the following categories:

-

Actively control functions and manage their own and

group generated content.

-

Construct knowledge individually or with others through

interaction, production, organization of

information, and critical review.

-

Interact with others (peers, instructor, and external

individuals) in multiple ways.

-

Observe and review records of assessment, historical

records, and feedback from others (both peer and

instructor).

-

Share information, materials, production, and identity.

-

Access course materials and expert knowledge as needed

and desired.

The 35

items were all observable and situated in learner

action through system functions so that little was

left up to the observer’s interpretation. For

example one item was “learners

can set up/initiative discussion, edit, share,

delete, and compile discussions” and ”Content can be

accessed from other technology (phone, PDA, Chumby™,

etc.).” Each item was rated according to

evidence of support for a learning principle on a

scale of one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly

agree). Results were coded to identify patterns of

principles, and patterns of systems. Additional,

total scores were generated to reveal the highest

scoring system.

Through publications (edutools™; Jaschik, 2007;

Wicks & Hitchcock, 2007; Wyles, 2004), evaluation

system (EduTools), and L/CMS subscription

information (e.g., Angel™, Blackboard™,

Desire2Learn™, eClassroom™, Educator™, Moodle™,

Sakai™, UCompass™, WebCT™), five L/CMS were

identified as the most prominently utilized systems

in K-20 education. These include: Angel™,

Blackboard™, Educator™, Moodle™, and WebCT™.

Collectively the authors have used all but Angel™

and Educator™. The authors were able to login to

course shells to ‘observe’ and record their

findings. A decision was made not to consider

plug-ins or add-ons that might expand capacity to

limit the complexity of the analysis. The L/CMS was

considered to be a basic classroom that could be

enhanced but just as brick and mortar classrooms,

might often not be. The authors also intentionally

did not visit active courses – it was intended that

the focus was on the system and not the

instructional designs or user actions.

Once the researchers had analyzed all L/CMS, they

compared scores and revisited disagreements of more

than one degree. Once agreement was reached, totals

were tallied and patterns across systems were

analyzed and described.

Findings

Two

systems were foremost in supporting both

constructivst and connectivist theoretical learning

frameworks: Angel™ and Educator™. Both systems

scored highest in giving the learner a degree of

control of what they experienced in the L/CMS;

providing opportunities for learners to connect with

each other through communication and interaction

functions; giving the learner access a variety of

content types, and allowing for learner

contributions to group processes and organizations.

These two systems were the only ones not used by

either author. It is possible that the authors may

have a bias toward the L/CMS hat they have used,

knowing more deeply the limitations of the systems

with which they are most

familiar. However, both authors were unaware

of some features of the systems with which they had

experience and therefore we believe that bias was

limited.

General limitations

All

systems scored low on items related to peer

critique, individual reflection of progress over

time (e.g., as document in collected work with

feedback as in an electronic portfolio. Angel™ was

the exception), expert review or participation, peer

critique or review, performance directed learning

paths, automated response to performance, and

integration of external learning resources (such as

Second Life™ or other Web 2.0 applications). None of

the systems except Angel™ offered a function that

would allow learners to make their work publicly

available. None offered a mechanism to allow former

students back into a course (an administrative

decision) or a function that would attribute

intellectual property or meta- tagging of learner

productions. It is possible of course to add these

components into a system, but, given the basic

system, none were built to accommodate these

functions.

General support for learning principles

All

systems had multiple interactive communication

functions, some more than others including chat,

discussion, and whiteboard. Educator™ included more

advanced capabilities such as IM, virtual office

hours and who’s online. All systems offered some

form of content repository through which files could

be stored, published within the L/CMS, and for some,

shared with others. Only Educator™ offered a form of

branching paths for learners based on their

performance. Although this ability can be programmed

into the other systems, it is not a basic component.

Cognitive supports such as book marking and

note-taking were also limited or missing. All

offered a variety of assessment tools that provided

the instructor an opportunity to integrate

assessment but except for Educator™ that offers

practice assessments and directs the learner to

content after they have completed an assessment.

Discussion and Conclusions

For

the most part, all of the L/CMS represent neo- and

post-Fordist frameworks of education. Their progress

may reflect their history and originations:

·

Angel™ – Conceptualized by Ali Jafari at

Indiana University-Purdue

University Indianapolis (IUPUI) and offered as

OnCourse, as an institutional CMS, and then it was

released by the newly formed CyberLearning Labs,

Inc. in July 2000 and subsequently renamed ANGEL

Learning.

·

Blackboard™ – Founded in 1997, it offered its first

software package to

Cornell University in 1998. The company began by

producing consulting services to the

IMS Global Learning

Consortium.

·

Educator™ – Conceptualized by Ed Mansouri at

Florida State University, Educator™ was first

released in 1999.

·

Moodle™ – Designed by

Martin Dougiamas while he was at Curtain

University, it was first released in 2002

and supported through an

active users and designer group who are committed to

improving this open source system.

·

WebCT™ – Conceptualized in the mid-1990s by

Murray W. Goldberg

at the

University of

British Columbia

from which the company was formed and the system

released in 1996-1997.

All

of the systems were ‘born’ in the late 20th

century when traditions of Fordism were starting to

fade and constructivist pedagogical practices were

beginning to be situated in K-20 instructional

practices. However the pre-cursors of the L/CMS were

web pages and discussion boards, a poor model for

constructive and connected learning. As we continue

to move towards increasingly open, seamless, mobile,

social, and transparent learning, L/CMS as systems

are hard pressed to change the very architecture

that has contributed to the remarkable

transformation of online courses are offered – all

in a 10 year period. Web 2.0 applications are

serving as a further irritant particularly as the

sophistication of graphic user interface designs

that far out distance the seemingly archaic

interfaces of the L/CMS. Additionally, the

user-centeredness of Web 2.0 applications is so

compelling, that it is difficult to foresee how

administrator and instructor-driven L/CMS can afford

truly support effective and efficient learning

designs that can compete with the allure of these

tools. It is lazy for the authors to suggest that

L/CMS should drive their functions from a learning

principle directive because as an institutional

mainstay they have solved many organizational and

infrastructure challenges that cannot be overlooked.

More to the point it may be that L/CMS companies

look to the innovative companies who want and do

design add-ons that sometimes are and certainly can

support the learning theory that is so amiss in most

systems. Is this a symbiotic market generator that

may or may not nurture more and

improved learning.

We began this study by arguing that there is a disconnect between L/CMS

across the life of the learner. However, we conclude

that the disconnect is between the institutional

market and what we know about teaching and learning.

We are stuck in the era of the TV-dinner approach to

distributed learning; the cafeteria and bistro

approaches are slow to be supported by current

systems. Perhaps it is the need for companies to

re-think their mission and purpose in higher

education, and for clients to carefully examine for

what purposes, through what instructional designs,

and resulting in what outcomes these systems are

used. It is not really an issue of vendor +client

relations. As we have discovered, these more

prominently used systems for the most part require

active and informed instructional designers to make

what happens inside the system work. Institutions

must invest in understanding, supporting, and

accounting for the quality and rigor of learning

that should not be sacrificed for a one-stop course

in a box solution.

References

Adams, S., &

Burns, M. (1999). Connecting student learning and

technology. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational

Development Laboratory.

Arbaugh, J. (2002). Managing the on-line classroom-a

study of technological and behavioral

characteristics of Web-based MBA courses. Journal

of High Technology Management Research, 13(2),

203-223.

Berger, N. (1999). Pioneering experiences in

distance learning: Lessons learned. Journal of

Management Education, 23 (6), 684-690.

Bonk, C. J., & Cunningham, D. J. (1998). Searching

for learner-centered, constructivist, and

sociocultural components of collaborative

educational learning tools. In C. J. Bonk & K. S.

King (Eds.), Electronic collaborators:

Learner-centered technologies for literacy,

apprenticeship, and discourse (pp. 25-50).

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Buckley, D. (2002, January/February). In pursuit of

the learning paradigm: Coupling faculty

transformation and institutional change. EDUCAUSE

Review, 37(1), 28-38. Retrieved October 25, 2004,

from

http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/erm0202.pdf

Cambre, M., & Hawkes, M. (2004). Toys, tools &

teachers the challenges of technology. Lanham,

Md: ScarecrowEducation.

Centre for Learning & Performance Technologies.

(2007).

http://www.c4lpt.co.uk/recommended/top100.html

Diaz, V., & McGee, P. (2005). Managing knowledge:

Learning objects and digital repositories in higher

education. In Metcalfe, A. (Ed.) Knowledge

Management and Higher Education: A Critical

Analysis. IDEA Group Publishing.

Doolittle, P. E. (1999). Constructivism and

Online Education. Retrieved December 12, 2007

from http://edpsychserver.ed.vt.edu/workshops/tohe1999/pedagogy.html.

Dutch, M.,& Muddiman, D. (2000) Information and

communication technologies, the public library and

social exclusion, in D. Muddiman (Ed) Open to

All? : the Public Library and Social Exclusion,

chapter 15, Vol.3, pp. 106-127.

London:

Resource: The Council for Museums, Archives and

Libraries.

Edwards R. (1995). Different discourses, discourses

of difference: Globalisation, distance education and

open learning. Distance Education, 16 (2),

241-255.

Flynn, P. (2004). Applying standards-based

constructivism a two-step guide for motivating

elementary students. Larchmont, NY: Eye On

Education.

Foote, C. J., Vermette, P. J., & Battaglia, C.

(2001). Constructivist strategies meeting

standards and engaging adolescent minds.

Larchmont, N.Y.: Eye on Education

Jamieson, P., Fisher, K., Gilding, T., Taylor, P., &

Trevitt, A. C. F. (2000). Place and space in the

design of new learning environments. HERDSA

(Higher Education Research and Development), 19

(2), 221-237.

Jaschik, S. (2007). Shakingup the market. Inside

Higher Ed.retrieved December 17, 2007 from

http://insidehighered.com/news/2007/05/15/ecollege.

Johnson, (2000). GUI bloopers: Don’ts and do’s

for software developers and Wed designers.

Morgan Kaufmann..

Jonassen, D.H. (2000). Computers as

mindtools for schools: Engaging critical thinking

(2nd Ed.).

Upper Saddle River: Merrill.

Kersten, G. E., Kersten, M. A., and Rakowski, W. M.

(2002). Software and culture: Beyond the

internationalization of the interface. Journal of

Global Information Management, 10 (4), 86-101.

Retrieved on

April 10, 2004 from

http://interneg.org/interneg/research/papers/2001/01.html.

Lankshear, C. & Knobel, M. (2003). Do we have

your attention? New literacies, digital,

technologies and the education of adolescents.

In D. Alvermann (Ed.), New literacies and

digital technologies: A focus on adolescent

learners. New York: Peter Lang.

Lea, L., Clayton, M., Draude, B., & Barlow, S.

(2001). The impact of technology on teaching and

learning. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 24(2), 69-70.

McClelland, R. J. (2001). Web-based administrative

supports for university students. The

International Journal of Education Management, 15

(6) 2001, 292-302.

McGorry, S. Y. (2003). Measuring quality in online

programs. The Internet and Higher Education, 6

(2), 159 – 177.

Moore, G. (2002). A Personal View:

Distance Education, Development and the Problem of

Culture in the Information Age. In Reddy, V. and

S. Manjulika

(Eds.) Towards Virtualization: Open and Distance

Learning. (633-640). New Delhi, India: Kogan

Page.

Marlowe, B. A., & Page, M. L. (1998). Creating

and sustaining the constructivist classroom.

Thousand Oaks, Calif: Corwin Press.

Moser, K. (2006, March 30). Online courses aren't just

for home-schoolers anymore. Christian Science

Monitor, p. 14.

National Center for Academic Transformation (NCAT).

See http://www.center.rpi.edu/.

Neal, E. (June 1998). Does using technology in

instruction enhance learning? or, The artless state

of

comparative research.. The Technology Source.

Retrieved from

http://technologysource.org/?view=article&id=86.

Norris, D., Mason, J., & Lefrere, P. (2003). A

revolution in the sharing of knowledge: Transforming

e-Knowledge. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Society for

College and University Planning.

Partlow, K. M., & Gibbs, W. J. (2003). Indicators of

constructivist principles in Internet based courses.

Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 14

(2), 68-97.

Picciano, A. G. & Seaman J. (2007). K–12 online

learning: A survey of

U.S. school district administrators.

Needham, Mass: The Sloan Consortium.

Rennie, F., & Mason, R. (2004). The connecticon: Learning

for the connected generation.

Greenwich, Conn.: Information Age Publishing.

Salisbury, D., Pearson, R., Miller, D. & Marett, K.

(2002). The limits of information: A

cautionary tale about one course delivery experience

in the distance education environment. e-Service

Journal, 1 (2) 65-81.

Taylor, J. C. (2001). Fifth generation distance

education. Higher Education Series, 40.

Retrieved June 15, 2004 from http:// www.dest.gov.au/highered/hes/hes40/hes40.pdf

Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory

for the digital age. International Journal of

Instructional Technology and Distance Learning.

Retrieved on June 23, 2007, from http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm

Simonson, M., Smaldino, S., Albright, M., & Zvacek,

S. (2003). Teaching and learning at a distance:

Foundations of distance education (2nd Ed.). Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall,

Smith, R., & Marx, L. (1994). Does technology

drive history? The dilemma of technological

determinism.

Massachusetts:

MIT Press.

Tucker, B. (2007). Laboratories of

reform: Virtual high schools and innovation in

public education [Monograph]. Education Sector

Reports. Retrieved March 25, 2008, from

http://www.educationsector.org/usr_doc/Virtual_Schools.pdf

Ullman, C. & Rabinowitz, M. (2004). Course

management systems and the reinvention of

instruction. T.H.E. Journal. Retrieved

December 16, 2007 from

http://thejournal.com/articles/17014.

Webster, J. & Hackley, P. (1997). Teaching

effectiveness in technology mediated distance

learning.

Academy

of

Management Journal, 40 (6), 1282-1309.

Westerberg, T. (2007). Creating the high schools

of our choice. Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education.

Wicks, M., & Hitchcock, T. (2007, November 4).

Transforming learning management systems into

effective learning environments. Preconference

session presented at Virtual School Symposium,

Louisville,

Kentucky.

Wyles, R.

(2004).

Shortlisting of learning management system software.

Open Source-Learning Environment and Community

Platform Project.

Zanoni, P., & Janssens, M. (2005). Diversity

management as identity regulation in the Post-Fordist

productive space. In S. Clegg & M. Kornberger (Eds.)

Space, Organizations and Management Theory,

92-112.

Copenhagen:

Liber & Copenhagen Business School Press.