|

Online

Human Touch (OHT) Instruction and Programming: A

Conceptual Framework to Increase Student Engagement and

Retention in Online Education, Part 1

|

Kristen Betts

Drexel University

School of Education

Philadelphia, PA USA

kbetts@drexel.edu

|

|

Abstract

The long-term sustainability of online degree

programs is highly dependent upon student enrollment

and retention. While national growth in online

education has increased approximately 10% between

2005 and 2006 to 3.5 million students, student

attrition in online programs remains higher than

on-campus traditional programs (Allen & Seaman,

2007). To proactively address student attrition, the

Master of Science in Higher Education Program at

Drexel University has developed and implemented the

concept of Online Human Touch (OHT) instruction and

programming. This interactive and personalized

approach to online education has resulted in high

student retention rates and high levels of student

satisfaction. This article is the first of a

two-part series that focuses on OHT in online

education.

Key words:

Online education, distance education, instruction,

engagement, retention, attrition, online

communities, work-integrated learning, and

communication

|

|

Introduction

The conceptual framework for Online Human Touch (OHT)

instruction and programming was developed in 2005 to

proactively meet the needs of a new, fully online

Master of Science in Higher Education (MSHE) Program

in the School of Education at Drexel University.

Since the student market segment for the MSHE

Program was and continues to be higher education

administrators working throughout the United States

and abroad, it was imperative that the instruction

and programming a) actively engage students, b)

incorporate work-integrated learning, c) foster and

support community development, and d) personally

connect students to Drexel University as future

alumni. Furthermore, the OHT concept was developed

to strategically assist with student retention since

national online attrition rates range from 20% to

50% (Diaz, 2002; Frankola, 2001) and even as high as

70% to 80% (Dagger & Wade, 2004; Flood, 2002).

The OHT concept asserts that students are more

likely to persist in an online program if they are

engaged in and outside of their courses and if the

educational experience is personalized. This

involves much more than simply having students

participate in discussion boards, receive emails

from faculty, or work in online groups. The OHT

concept is a holistic approach that builds upon the

program director, faculty, adjunct faculty, and

staff developing a personal connection between

Drexel University and each student. The OHT concept

begins with the first point of contact that the MSHE

Program has with a potential student during the

application process. It is a bond based on human

interaction fostered through instruction,

programming, and personalized engagement with

potential students, matriculated students, and

alumni.

Over the past 3 years, the OHT concept has continued

to evolve through the emergence of new technologies

and data collected from MSHE students, faculty,

adjunct faculty, and staff. Moreover, policies,

procedures, and guidelines that support the OHT

concept have been developed for faculty and staff to

integrate into all aspects of the MSHE Program

(i.e., recruitment, advising, orientation,

instruction, events, etc.). To date, the

implementation of OHT instruction and programming

has been successful. Since fall 2005, the MSHE

Program has grown from its first cohort of 26

students to 145 students in spring 2008. The overall

average student retention rate for the past three

years is 83% which is higher than many on-campus

programs. MSHE alumni are also actively involved in

alumni groups across the United States and often

serve as guest speakers for MSHE online courses and

events.

Review of Literature

The proliferation and increasing affordability of

technology is providing new opportunities for

individuals seeking higher education degrees. In

fact, online enrollment is outpacing overall higher

education student enrollment rates in the United

States. According to Online Nation: Five Years of

Growth in Online Learning (Allen & Seaman,

2007), the enrollment rates for online education in

fall 2006 increased 9.7% while there was only a 1.5%

enrollment increase across the entire higher

education student population. Data also reveals in

fall 2006 that nearly 20% of all higher education

students in the United States were taking at least

one online course (Allen & Seaman, 2007).

National data relating to online student attrition

is limited. According to Eduventures (2007),

“Program-level online student retention and

completion data in the public domain is almost

non-existent. Delivery mode is not a variable used

by the National Center for Education Statistics, the

main source of retention and completion data for

U.S. higher education” (p. 4).

Data regarding online student attrition varies.

Online attrition is often cited as 20% to 50% within

the literature (Diaz, 2002; Frankola, 2001).

However, the literature also reveals that attrition

can be as high as 70% to 80% (Dagger & Wade, 2004;

Flood, 2002). There are other publications that cite

online attrition to be 10% to 20% higher than

traditional on-campus programs (Angelino, Williams &

Natvig, 2007; Carr, 2000). According to the National

Center for Educational Statistics, the national

six-year graduation rate for traditional on-campus

programs is 58% for undergraduate students (Knapp,

Kelly-Reid, Ginder, & Miller, 2008) which equates to

42% attrition. By combining national undergraduate

attrition data (NCES, 2008) and online attrition

estimates (Angelino, Williams & Natvig, 2007; Carr,

2000) then the national online attrition rate would

be approximately 52% to 62%. This means that

institutions are losing half or more of all students

who enroll in online programs.

Why do online students leave? Online education

provides many challenges to students including

isolation and feeling disconnected (Angelino,

Williams, & Natvig, 2007; Bathe, 2001; Stark &

Warren, 1999). The literature also indicates that a

lack of personal interaction and support are major

reasons that lead to student attrition (Moore &

Kearsley, 1996). Additionally, online students are

not land locked to a given geographic area.

Therefore, if students are not satisfied or decide

they would like to enroll in a different program,

other nationally accredited degree programs are just

one click away.

OHT Instruction and Programming Concept

In an effort to proactively address online attrition

and create a lifelong bond with future alumni, the

OHT instruction and programming concept was

developed and implemented within Drexel University’s

MSHE Program. This personalized approach to online

education has resulted in continued program growth,

financial sustainability, high student retention

rates, active alumni participation, and national

recognition for best practices in online education

by the United States Distance Learning Association (USDLA)

in April 2008.

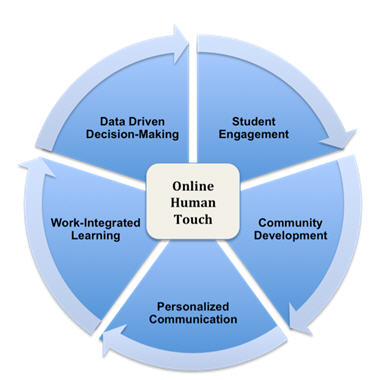

The conceptual framework supporting the development

of OHT instruction and programming builds upon five

areas of research including:

I.

Student Engagement

(Astin, 1984; Chickering & Gamson, 1987; Tinto,

1975, 1993);

II.

Community Development

(Johnson, 2001; Palloff & Pratt, 1999;

Stanford-Bowers, 2008);

III.

Personalized Communication

(Faharani, 2003; Kruger, Epley, Parker & Ng, 2003;

Mehrabian, 1971);

IV.

Work-Integrated Learning

(Boud, 1991; Kolb & Fry, 1975; Milne, 2007); and

V.

Data Driven Decision-Making

(Cranton & Legge, 1978; Scriven, 1967).

Figure 1 illustrates the interconnection between the

five areas of research that support the OHT concept.

While each area of research independently

contributes to the overall student experience, it is

when all five areas are strategically integrated

into instruction and programming that they fully

support the conceptual underpinnings of OHT.

Figure 1. OHT Instruction and Programming Concept

An overview is provided to further describe the five

areas of research that support the OHT instruction

and programming concept. Additionally, examples are

provided to illustrate how each area of research is

integrated into OHT instruction and programming to

support the conceptual framework.

I. Student Engagement and OHT Strategies

The OHT concept builds upon Tinto’s theory of

student departure (1975, 1993). Tinto’s (1975)

research reveals that the more students are engaged

in the college community, the less likely they are

to depart. Tinto identifies lack of social and

academic integration into the college community as

factors that lead to student attrition. Further

research into student departure (Chickering & Gamson,

1987; Tinto 1993) reveals the more opportunities

provided for student engagement within the college

community, the more likely students will become

engaged and connected which consequently can lead to

greater student persistence.

Research by Chickering and Gamson (1987) identifies

frequent faculty-student contact in and outside the

classroom as the most important factor in student

motivation and involvement. However, for fully

online programs, the lack of on-campus physical

attendance provides distinct challenges since this

limits opportunities for student engagement and

involvement. This is of particular concern since

Astin’s (1975) theory of involvement reveals that

student departure is associated with noninvolvement

on-campus.

The OHT concept extends the work of Tinto (1975,

1993, 2006), Chickering and Gamson (1987) and Astin

(1984) by asserting that online students must be

involved strategically in the campus community

through instruction and programming to increase the

likelihood of student involvement. Therefore, online

programs need to identify ways in which they can

bring the campus to the students through

innovative and personalized instruction and

programming.

According to Angelino, Williams and Natvig (2007),

challenges to online education include physical

isolation, lack of support, and feeling

disconnected. Therefore, the OHT concept promotes

the development of proactive strategies that engage

students in the online environment even prior to

matriculation to encourage and foster student-campus

connectivity. Furthermore, the OHT concept promotes

integrating academic and social networking

activities into courses and programming to support

ongoing student-campus connectivity.

The OHT concept is employed by MSHE faculty, adjunct

faculty, and staff throughout the two-year program

(i.e., recruitment, advising, orientation,

instruction, events, etc.). However, there is

particular emphasis on student engagement and

personal connection to Drexel University during the

first two quarters. Since the majority of student

attrition in the MSHE Program occurs within the

first two quarters (87%), connecting students early

to peers, faculty, adjuncts, staff, and Drexel

University is critical.

Included below are four examples of how student

engagement is integrated into OHT instruction and

programming.

Student Recruitment:

Potential students who submit inquiries and

enrollment applications to the MSHE Program receive

personalized email invitations to participate in

Live Open Houses similar to on-campus programs. The

Live Open House sessions support human

interaction through personal

introductions to the MSHE Program Director, Academic

Advisor, current students, and alumni. Through an

interactive PowerPoint presentation, potential

students are engaged in polling, asking programmatic

questions, and talking with other potential

students, current MSHE students, and MSHE alumni.

These Live Open House sessions are particularly

important to cultivating a connection with potential

students since less than half of the MSHE students

(47%) reside in Pennsylvania and only 20% of all

MSHE students reside in Philadelphia. For the

majority of the MSHE students, their first time on

campus is at graduation.

Student Support Services:

The MSHE Program strategically integrates student

support services into courses. For introductory

courses, students are invited in Week 2 to attend a

Horizon Wimba Live Classroom lecture where they

introduce themselves to their classmates (optional

voice, text, or video) and they are personally

introduced to student support services staff at

Drexel University who discuss academic services

offered by their program or division. Support

services staff include (a) the Information Services

Librarian, (b) an Online Learning Support

Specialist, and (c) a representative from the

Writing Center. Each support services specialist

shares a short PowerPoint presentation highlighting

their departments’ services and then answers

questions. As students progress through the MSHE

Program, they are personally introduced

through their courses to additional student support

services specialists representing the Steinbright

Career Development Center, Office of Research

Compliance, Office of Information Resources &

Technology, and Institutional Advancement.

Links to Online Campus Events:

To further connect and engage students in the campus

community, students are invited by the MSHE Program

Director several times during the year to

participate in on-campus events that are offered

online through streaming video accessible by

electronic links. In fall 2007, students were

invited to watch the United States Democratic debate

held on Drexel University’s campus. In spring 2008,

students were invited to electronically attend an

educational technology conference held on-campus. In

June 2008, MSHE students were invited to watch

Drexel University’s graduation through a live link

to support their graduating peers. This link enabled

MSHE students who were graduating the opportunity to

share this exciting event with family members and

friends who were unable to attend the graduation

ceremony in person but wanted to be part of the

celebration.

On-campus Annual Conference:

The MSHE Program offers a one-day conference at

Drexel University to provide students with an

opportunity to physically come to the Philadelphia

campus and meet classmates, faculty, adjuncts,

staff, and administrators (Dean, Vice Presidents,

Associate Vice Presidents, and Directors). This

one-day conference includes a welcome breakfast

where all attendees introduce themselves. There are

two panel presentations. The first panel

presentation includes current students and alumni

who discuss their experience in the MSHE Program as

well as answer questions from the audience. The

second panel presentation includes faculty,

adjuncts, and administrators who discuss current and

emerging issues in higher education. Additionally,

there is a series of workshops presented throughout

the day on topical issues relating to Drexel

University (student and academic resources), the

MSHE Program, and the MSHE academic areas of

specializations (Higher Education Administration & Organizational Management;

Institutional Research & Planning; Enrollment

Management; and

Academic Development, Technology & Instruction).

Students in the MSHE Program also have an

opportunity to present workshops. The conference

concludes with a campus tour and a networking

reception. Students who are unable to come to campus

are able to watch and participate in the panel

sessions and workshops through Mediasite Live.

Recorded sessions are made available to all students

through the MSHE Resource Portal. The MSHE

conference is being expanded to include additional

online programs so students are able to academically

and socially network with students outside of the

MSHE Program to further foster ongoing student

engagement and connectivity to Drexel University.

II. Community Development and OHT Strategies

The OHT concept asserts that community development

is critical to student engagement, connectivity to

the institution, and retention in online education.

Therefore, administrators and faculty need to

develop strategies to promote and support academic

and social community development for online

students. With on-campus programs there is a natural

integration of students into freshmen seminars, core

courses, or assigned rooms in resident halls that

typically support community development. However, in

the online environment, community development must

be strategically integrated into instruction and

programming. As stated by Palloff and Pratt (1999):

It is really up to those of us involved with the use

of technology in education to redefine community,

for we truly believe we are addressing issues here

that are primal and essential to the existence of

electronic communication in the educational arena.

(p. 23)

The OHT concept builds upon the research of

Johnson (2001) and Stanford-Bowers (2008).

Literature for on-campus traditional education

programs indicates that student retention is linked

to student integration into the campus community and

the first year experience (Angelo, 1997; Tinto,

1982; Kuh, 2003). According to Johnson (2001),

student retention is linked to engagement in the

learning environment beginning the first month

on-campus. Furthermore, Johnson (2001) states, “The

chances of staying beyond the first year rise as

connections are made and academic and social

integration are achieved” (p. 220). Within online education, research by Stanford-Bowers (2008)

indicates that building community online is crucial

for influencing student persistence but just being

part of an electronic learning environment does not

guarantee community.

The OHT concept extends the research by Johnson

(2001) and Stanford-Bowers (2008) and asserts that

community development begins with the recruitment

process and continues through matriculation and

graduation. Moreover, the OHT concept purports that

students should be engaged in numerous academic and

social communities throughout their enrollment to

create a sense of inclusion. These diverse

communities increase online student involvement and

connectivity which can increase retention and

ultimately alumni engagement.

The OHT concept asserts that students must be

presented with community development opportunities

through courses and extra curricular activities.

These academic and social communities should

encourage and support student interaction on a

weekly, monthly or quarterly basis depending upon

the particular community. In an online environment,

community development relies heavily on programming,

course design, and instruction. Community

development is not simply developing a virtual

campus or an online resource portal that includes an

infinite number of electronic links to student

resources and chat rooms. Online administrators must

design meaningful opportunities for students to

interact with their peers, faculty, adjuncts, and

staff in a supportive and inclusive

environment.

Included below are four examples of how community

development is integrated into OHT instruction and

programming.

Audio/Text Introductions:

To foster community development among newly

matriculated MSHE students, students and faculty are

required to post audio/voice and text

self-introductions in the core courses the first

week of class. The self-introductory topics include

name, place of residence (city/town and state),

place of employment, academic background,

professional focus/expertise, research interests,

and hobbies/interests. Students are then asked to

respond to at least two classmates during the first

week of class. It is common to have over 100 posts

in the first week by students who are connecting and

bonding with new classmates.

Weekly Discussion Boards:

To further extend community development

opportunities among students, weekly discussion

boards have been designed to provide unique

opportunities for students to respond to sets of

questions relating to current issues or to actively

participate in asynchronous text or audio/voice

debates and/or role-plays. Students are required to

respond to classmates following their initial

posting. Through these interactive discussions,

academic and social communities begin to emerge as

students engage with peers who share similar

academic and professional interests.

Virtual Teas:

Virtual teas are held through Horizon Wimba Live

Classroom or in Second Life. Typically students from

two or more classes are invited to discuss

current/emerging higher education issues or they are

introduced to new technologies. Students are sent an

email invitation to attend the virtual tea. Students

also are sent a signed invitation in the mail with a

sachet of tea so they can join their classmates for

the virtual tea. The virtual teas provide an

informal opportunity for students, faculty, and

adjuncts to interact in a relaxed environment that

supports learning, engagement, and community

development. Students are able to speak and

text-chat with faculty, adjuncts, guest speakers,

and/or their classmates while they enjoy their

tea.

Group Assignments & Presentations:

Throughout the MSHE Program students must complete

group assignments that require asynchronous or

synchronous presentations. In some MSHE courses

students are placed in groups of two or three based

on their area of professional expertise or research

interest while in other courses students are able to

select group participants. Assignments are

“real-life” scenarios in which students must conduct

research and present findings to various assigned

“audiences” in a simulated role-play scenario such

as the Board of Trustees, President, students,

national conference, etc. Students use Camtasia or

Impatica for the asynchronous presentations. Horizon

Wimba Live Classroom is used for the “live”

(synchronous) presentations which enables presenting

groups to answer questions from the defined

audience. The group assignments and presentations

provide students with extensive opportunities to

expand their academic and social networks.

III. Personalized Communication and OHT Strategies

Communication and engagement are essential to

connecting students to an institution and increasing

student persistence. According to Tinto (2006), “Frequency

and quality of

contact with faculty, staff, and students has

repeatedly

been shown to be an

independent

predictor of student persistence” (p. 2).

Moreover, Chickering and Gamson (1987) state that

knowing faculty and faculty concern assist students

get through challenging times and enhance students’

intellectual commitment. However, in online

education, frequency and quality of contact need to

be defined and outlined for faculty, adjuncts, and

staff. Online policies and guidelines need to be

developed to establish expectations for

faculty-to-student and staff-to-student

communication. Additionally, faculty, adjuncts, and

staff need to be trained on inherent differences

between face-to-face and online communication.

Interaction in a face-to-face classroom is

predominately based on verbal and nonverbal

communicative behaviors (Farahani, 2003). However,

in an online program communication is primarily text

oriented and email is a primary form of

communication. According to Mehrabian, author of

Silent Messages (1971) and Non-Verbal Communications

(1972), face-to-face communication is broken down

into three categories: 55% is non-verbal, 38% is

tone and 7% is words. Over the telephone

communication is broken down into two categories:

86% is tone and 14% is words (International Customer

Management Institute, 2008; Lockwood, 2008). These

percentages for communication are important when

considering course development for online programs

particularly since non-verbal communication and tone

can be limited or non-existent in asynchronous

programs.

In terms of email, communicating may not be as easy

as type and send. Kruger, Epley, Parker and

Ng (2005) conducted research to examine

communication and interpretation of tone in emails.

The research showed that participants who sent

emails overestimated their ability to communicate by

e-mail and that participants who received emails

overestimated their ability to interpret e-mail.

According to Winerman (2006), the study by Kruger,

Epley, Parker and Ng (2005) revealed that

participants who sent emails predicted about 78% of

the time their partners would correctly interpret

the tone. The data revealed that only 56% of the

time the receiver correctly interpreted the tone.

Moreover, the receivers “guessed that they had

correctly interpreted the message's tone 90% of the

time” (Winerman, 2006, p. 16). While email is a

common form of correspondence in online education,

ensuring the correct message or intended message is

being sent is imperative.

The OHT concept asserts that personalized

communication creates a supportive, nurturing, and

respectful learning environment. Moreover, the OHT

concept stresses that faculty, adjuncts, and staff

must be trained on how to effectively communicate

online. Policies and guidelines must be developed to

provide a foundation and framework that supports

frequency and quality of personalized feedback using

multiple modes of online communication (i.e., text

email, audio/voice email, text discussion boards,

audio/voice discussion boards, podcasts, text

announcements, audio/voice announcements, phone

calls, etc.). Instituting high expectations for

communication, particularly personalized

communication, is essential to connecting students

to an institution and increasing student

persistence.

Included below are four examples of how personalized

communication is integrated into OHT instruction and

programming.

Congratulations and Welcome Calls:

When applicants are accepted to the MSHE Program,

each student receives a personal phone call from the

MSHE Director welcoming them to Drexel University

and congratulating them on their acceptance. Within

one week, another personal phone call is placed by

the MSHE Academic Advisor. These calls are placed to

personally connect the potential student to

the MSHE Program and Drexel University.

Using Names in All Correspondence:

MSHE policies and guidelines reinforce the

importance of making students feel they are truly

individuals in the MSHE Program and not just a

number or attached to a cohort. The policies and

guidelines strongly recommend and encourage faculty,

adjuncts, and staff to refer to students by their

first name in all correspondence (i.e., text

email, audio/voice email, discussion boards, podcast

critiques, phone calls, letters, etc.). The use of

personal names in all correspondence is much like

eye contact, a handshake, a friendly smile, or a

head nod that students often naturally see in a

face-to-face classroom. Developing a connection and

bond with students early in their enrollment is very

important since students work with the MSHE faculty,

adjuncts, and staff over a two-year period.

Individualized Feedback on All Graded Assignments:

MSHE faculty and adjuncts are required to provide

individualized comments throughout submitted graded

assignments (i.e., typed comment boxes/tracking

using Reviewing in Microsoft Word or written

comments using a tablet PC). These personal comments

provide students with an opportunity to see what

they have done well and what they need to modify.

Faculty and adjuncts are also advised to use a

constructive layered approach to providing

individualized feedback on graded assignments in an

effort to leave little chance for possible negative

interpretation by students. The constructive layered

approach provides students with (a) positive

comments on overall aspects of the document, (b)

constructive criticism citing specific areas that

need modification, and (c) summative constructive

comments that provide recommendations for the

document and/or upcoming assignments. The

personalized comments on each student’s assignment

are intended to (a) engage students in the learning

and evaluation process, (b) identify areas that need

improvement, and (c) motivate students to utilize

the feedback.

Audio/Voice Announcements, Emails, Discussion Boards

& Podcasts:

MSHE faculty and adjuncts are trained to integrate

audio/voice communication into the courses to

personalize instruction and feedback. Audio/voice

communication includes announcements, emails,

discussion boards, and podcasts. MSHE policies

require faculty to post several weekly announcements

for students. These announcements can be a

preliminary overview of the weekly lecture,

commentary regarding current issues relating to the

weekly lecture, reminders about upcoming

assignments, a weekly wrap up that highlights the

lecture and discussion board, etc. The MSHE Program

encourages augmenting text announcements with

audio/voice announcements since this provides

faculty and adjuncts with an opportunity to speak

to the students in the classes and adds a human

touch to an online course that could easily be

completely text-based. Individual audio/voice emails

are typically sent to students by faculty and

adjuncts in the first week of class to welcome

students to the course. This is much like the

personalized welcome students receive when they come

to class on campus correlating to a virtual smile,

eye contact, and handshake. Audio/voice emails are

also used to provide individual and group feedback

on assignments to augment written comments. It

should be noted that that MSHE faculty, adjuncts,

and staff are expected to respond to student emails

(text or audio/voice) within 24 to 36 hours as

stated in the MSHE policies and guidelines.

Audio/voice discussion boards are integrated into

all MSHE courses and support student debates and

role-plays. Audio podcasting is a requirement for

some graded assignments. For example, students are

put into groups of two prior to submitting a final

paper. They exchange final drafts of their papers

and then record an audio podcast of their comments

with detailed feedback regarding the paper. Students

then send the audio podcast to their partner. The

audio podcasts allow students to provide

individualized and personalized feedback to their

partner page by page which is similar to working in

groups in a classroom setting.

IV. Work-Integrated Learning and OHT Strategies

Work-integrated learning builds upon the

experiential learning model developed of Kolb and

Fry (1975) that includes four points: concrete

experience, observation and reflection, formation of

abstract concepts, and testing in new situations.

While Kolb and Fry (1975) state that the learning

cycle can begin at any of the four points of the

model, they recommend that the learning process

start with an individual identifying an action that

will be carried out and observing the effects as

they relate to the action within the selected

environment.

Boud’s (1991) research on self-assessment and reflective learning builds upon Kolb and Fry’s point on observation and reflection . According to Boud (1991) self-assessment challenges

students to think critically about what they are

learning and to select appropriate performance

standards to use in their work. Boud (1991) states

that “Self-assessment encourages students to look at

themselves and to other sources to determine what

criteria should be used in judging their own work

rather than being dependent solely on their teachers

or another authorities” (p. 1).

Milne (2007) developed a model for work-integrated

learning in which academics and mentors collaborate

to provide student learning experiences. This

work-integrated learning model expands the work of

Alderman and Milne (2005), Boud (1991), Kolb (1984),

and Murray (1991). According to Milne (2007):

As properly planned, designed and monitored learning

experiences that expose students to professional

culture and workplace practice they ensure an easier

transition from study to employment as well as

developing knowledge, skills, and attributes that

are difficult to foster with academic studies alone.

(p. 1)

Building upon the research of Milne (2007), Kolb and

Fry (1975), Boud, (1991), the OHT concept asserts

that work-integrated learning applied to online

instruction and programming increases a student’s

involvement in their courses. This meaningful

involvement, increases the value of the program to

the students and thus increases student engagement

and retention.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there

are

an estimated 6,000 jobs in higher education

administration that will need to be filled through

2014 as a result of the growth and retirement within

higher education (Leubsdorf, 2006). With the growing

number of professional opportunities in higher

education, there is a need for skilled

administrators to fill these positions. Therefore,

the MSHE Program has incorporated work-integrated

learning into instruction and programming to provide

students with the knowledge, skills, and experience

needed to fill employment opportunities. OHT

strategies include real-life work-based assignments,

mock interviews, ePortfolios, and reflective

journals and papers.

Included below are four examples of how

work-integrated learning is integrated into OHT

instruction and programming.

Practice-Based Assignments:

All graded assignments for the MSHE Program are

developed by higher education administrators and

require students to address current and emerging

issues through individual and group assignments.

Assignments often require students to conduct

strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat (SWOT)

analyses or environmental scans relative to a

particular issue. Additionally, students must

develop PowerPoint presentations to share their

findings with classmates through Horizon Wimba Live

Classroom similar to when administrators or

committees present to faculty, staff, the public, or

the Board of Trustees. These practice-based

assignments allow students to apply the skills and

knowledge they are acquiring from the MSHE courses

to actual problems within higher education and

challenge students to identify or develop solutions.

ePortfolios:

In the EDHE 606: Higher Education Career Development

course, MSHE students are required to identify a

“real” job posted in the Chronicle of Higher

Education that would be considered their next

professional career step upon completion of the

MSHE Program. Students develop an ePortfolio that

includes a cover letter for the position, resume,

and professional biography. They are required also

to include three to five sample documents (e.g.,

projects from their current employment position,

papers or projects from the MSHE Program, etc.), and

a list of three references. The ePortfolio is

submitted to Drexel University’s Steinbright Career

Development Center (SCDC). Students receive detailed

feedback from SCDC staff and the EDHE 606 professor

regarding the ePortfolio. The ePortfolio is later

required to be updated and submitted by all students

as part of the MSHE master’s defense. The

development of the ePortfolio provides students with

an opportunity to prepare for career advancement or

transition into higher education.

Learning Simulation:

As part of the EDHE 606: Higher Education Career

Development course, MSHE students are required to

participate in a mock interview using Horizon Wimba

Live Classroom or Second Life. This simulated

assignment builds upon the ePortfolio that is

required for EDHE 606. Once students send their

ePortfolios to the SCDC, they receive an email from

the SCDC stating they are finalists for the position

for which they applied. The email also states

students are required to present a PowerPoint

presentation as part of the final interview process

to serve as (a) a self-introduction, (b) highlight

their professional skills and experience, and (c)

state why they are the best candidate for the job.

This mock interview includes a search committee

comprising of the professor teaching EDHE 606 and a

representative from the SCDC. During the mock

interview, the search committee asks specific

questions relating to the advertised position, the

student’s background, and submitted ePortfolio. The

search committee completes two evaluations following

the simulated interviews covering (a) the content

and (b) the interview/presentation. The search

committee members then send each student their two

evaluations with personalized text comments and an

audio/voice email providing constructive feedback.

Reflective Journals and Papers:

In several of the MSHE courses, reflective journals

or reflective papers are required. The reflective

assignments provide students with an opportunity to

share with faculty their academic and professional

development throughout the course. The reflective

journals provide a more informal and personalized

format that enables students to self-evaluate their

own learning. An evaluation criteria for the

journals provides students with an outline of what

to include in the reflective, self-assessments

including meeting expected outcomes, the acquisition

of knowledge and skills from course lectures, newly

honed skills from experiential learning, etc.

V. Data Driven Decision-Making and OHT Strategies

The OHT concept builds upon research by Cranton and

Legge (1978) and Scriven (1967) that focuses on the

importance of evaluation and need for data driven

decision-making in higher education. According to

Cranton and Legge (1978), “evaluation can be

discussed along two major dimensions: formative

versus summative and internal versus external” (p.

464).

Formative evaluation is conducted during a program

to assist with development and improvement (Scriven,

1967). Summative evaluation is conducted at the end

of a program to measure effectiveness and value (Scriven,

1967). According to Cranton and Legge (1978), “it is

often the case that formative evaluations are

internal and summative evaluations are external;

however, this division is by no means necessary” (p.

465). Formative internal evaluations are typically

conducted by faculty involved in the program while

summative external evaluations are conducted by

employees outside of the program and tend to be for

the purpose of accountability (Cranton and Legge,

1978). The data garnered from program evaluation in

higher education is critical for assessing content,

value, engagement, and outcomes that ultimately

support data driven decision-making. Data driven

decision-making has and continues to serve as a

cornerstone in the development and continuous

quality improvement of the MSHE Program. According

to Microsoft (2004), “With effective data driven decision making capabilities, higher

education administrators and staff can more

accurately identify trends, pinpoint areas that need

improvement, engage in scenario-based planning and

discuss fact-based decision making options and

likely outcomes” (p. 1).

Data driven decision-making is not new to education.

“Notions of data driven decision-making (DDDM) in

education are modeled on successful practices from

industry and manufacturing, such as Total Quality

Management, Organizational Learning, and Continuous

Improvement, which emphasizes that organizational

improvement is enhanced by responsiveness to various

types of data” (Marsh, Pane & Hamilton, 2006, p. 2).

Included below are four examples of how data driven

decision-making is integrated into OHT instruction

and programming.

MSHE Annual Student Survey:

The MSHE Annual Student Survey is conducted at the

end of each spring quarter and provides critical

benchmarking data relating to student engagement,

retention, academics, satisfaction, and professional

development. While the core of the survey is

consistent annually, a portion of the survey is

modified each year to collect data on new OHT

initiatives or ideas that have been or will be

incorporated into instruction or programming.

Key Learning Points:

During Weeks 5 and 10 in all courses, students are

required to post Key Learning Points through an

audio/voice discussion board. Students are provided

3-4 minutes to summarize and articulate the

knowledge and skills they have acquired and applied

during the first five and last five weeks of the

course. Through this reflective assignment, students

often share accolades and challenges they have

experienced in the program or at their place of

employment as they relate to the lectures.

Additionally, students share with faculty new

relationships they have acquired through discussion

boards, Live Classrooms, or virtual teas. These

personal accounts provide faculty an opportunity to

assess student involvement in the lectures as well

as connect to students through their shared

experiences.

Exit interviews for Non-degree Completers:

Students who decide to leave the MSHE Program

without completing the degree are first contacted by

the MSHE Academic Advisor to discuss their reasons

for leaving prior to graduating. This preliminary

exit interview provides the Academic Advisor with

the opportunity to personally reach out to the

student and share options for continuing enrollment.

For students who make the final decision to leave

the MSHE Program, a second interview is set up with

the MSHE Director. This discussion with the MSHE

Director provides an additional opportunity to reach

out to students and to identify specific reasons as

to why they are leaving the MSHE Program. Attrition

data is collected and added to the MSHE Program

database to identify and monitor current or emerging

enrollment issues.

Continuous Quality Improvement and Innovation:

The MSHE Program works closely with the Office of

Research Compliance throughout the academic year to

conduct quantitative and qualitative research

relating to continuous quality improvement and

satisfaction with new instructional strategies

and/or new technologies. Instead of surveying the

entire MSHE student population on all studies,

select courses throughout the year are chosen for

the implementation of new instructional strategies

and use of new technologies. At the end of the

courses, students complete electronic surveys and/or

participate in focus groups regarding their

experience. Based on the collected feedback, the

instructional strategies and/or new technology are

implemented on a larger scale or across the entire

program. Past studies have shown this mixed methods

approach to be very important and cost effective.

For example, two dynamic technology platforms

that have garnered national attention received very

poor reviews from MSHE students; therefore, they

were not implemented on a full program scale.

Student surveys revealed the platforms were

extremely cumbersome and difficult for students to

use in the courses. Conversely, there have been

instructional strategies applied across three to

four courses that were extremely successful and

later implemented across all courses.

Results of OHT Instruction and Programming

Data collected from the MSHE Program over the past

three years supports the value of OHT and the

ongoing development of this dynamic and evolving

concept. Comparative data is not available since the

OHT instruction and programming concept was

developed in fall 2005 to support the launching of

the new online MSHE Program which did not and still

does not exist as an on-campus program. Descriptive

data and feedback garnered from three types of

evaluation will highlight the critical role of OHT

instruction and programming in the MSHE Program: (a)

2008 Annual MSHE Student Survey; (b) 2008 course

evaluations; and (c) student feedback from

reflective papers and reflective journals.

2008 MSHE Annual Student Survey

In June 2008, the MSHE annual student survey was

sent to 144 students enrolled in the MSHE Program in

spring quarter 2008. Over half of the students

(N=75) responded representing a 52% response rate.

The purpose of the annual survey is to collect

student data relating to student engagement,

retention, academics, satisfaction, and professional

development.

The results of the 2008 survey indicate students

feel highly connected to MSHE faculty and adjuncts

as well as students in their cohort (see Table 1).

While MSHE students feel less connected to the

School of Education and Drexel University, they feel

least connected to MSHE students outside of their

cohort.

MSHE students are actively engaged in educational

activities that are integrated into instruction and

programming. MSHE data revealed high levels of

student engagement in weekly discussion boards,

group assignments, and Horizon Wimba Live lectures

(see Table 2). However, students are less engaged in

the audio/voice chat rooms and text chat rooms that

are supplementary and not integrated into courses.

Text and audio/voice communication and feedback are

important in connecting students to the MSHE

program. The majority of students indicated that

text comments on graded assignments made them highly

connected to the MSHE Program. Furthermore, the data

revealed that weekly discussion boards,

announcements, emails, and “live” classroom lectures

connect students more to the MSHE Program than

recorded video lectures or recorded voiceover PPT

presentations (see Table 3).

Table 1. Question:

As an online student in the MSHE Program how

connected do you feel to the following constituent

groups?

|

|

Connected |

Very connected |

Total |

|

Faculty and adjuncts |

51% |

18% |

69% |

|

Your cohort |

55% |

12% |

67% |

|

School of Education |

35% |

11 % |

46% |

|

Drexel University |

32% |

10% |

42% |

|

MSHE students outside of your cohort |

12% |

1% |

13% |

Likert scale: Very connected, Connected, Neutral,

Disconnected, Very Disconnected

Table 2. Question:

As an online student how engaged are you with the

following course activities?

|

|

Engaged |

Very engaged |

Total |

|

Weekly Discussion Boards |

39% |

53% |

92% |

|

Group Assignments |

26% |

62% |

88% |

|

Horizon Wimba Live Classroom lectures offered by

faculty and adjuncts |

42% |

45% |

87% |

|

Audio/voice Chat Rooms |

24% |

19% |

43% |

|

Text Chat Rooms |

21% |

12% |

33% |

Likert scale: Very engaged, Engaged, Neutral,

Disengaged, Very Disengaged

Table 3. Question: Rate the level to which each educational activity makes you feel connected as a student to the MSHE Program.

|

Connected |

Very connected |

Total |

Text comments on graded assignments |

41% |

53% |

94% |

Weekly Discussion Boards (text) |

45% |

47% |

92% |

Text announcements |

46% |

43% |

89% |

Text email |

52% |

36% |

88% |

Audio/voice announcements |

45% |

39% |

84% |

Live Classroom lectures presented by faculty and adjuncts |

35% |

49% |

84% |

Live Classroom lectures presented by individual students and groups for graded assignments |

40% |

43% |

83% |

Audio/voice comments on graded assignments |

30% |

48% |

78% |

Audio/voice email |

34% |

42% |

76% |

Weekly Discussion Boards (Audio/Voice) |

33% |

43% |

76% |

Video lectures by faculty/adjuncts |

30% |

27% |

57% |

Voiceover PPT/Camtasia presentations by faculty/adjuncts |

34% |

23% |

57% |

Likert scale: Very connected, Connected, Neutral, Not very connected, Not connected at all

MSHE data revealed that 100% of the students

identified quality of instruction and academic rigor

of courses as important and very important to their

overall master’s degree experience. Academic support

from faculty and adjuncts as well as accessibility

also had high ratings of importance to students. In

addition, students indicated technical support,

quality and accessibility of academic advising, and

connecting with faculty and MSHE students were of

high importance to their overall master’s degree

experience (see Table 4).

Students were asked to rate their professional

skills prior to enrolling in the MSHE Program and

then their current skills since enrolling in the

MSHE Program. The data revealed that students

increased their skill level between 9% and 45% since

enrolling in the MSHE Program (see Table 5).

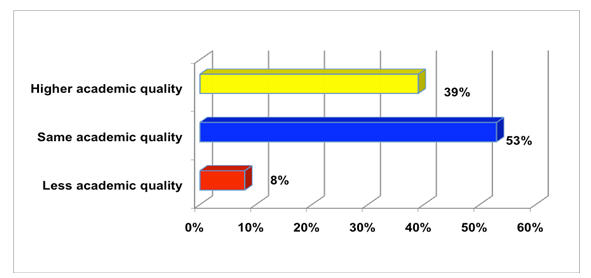

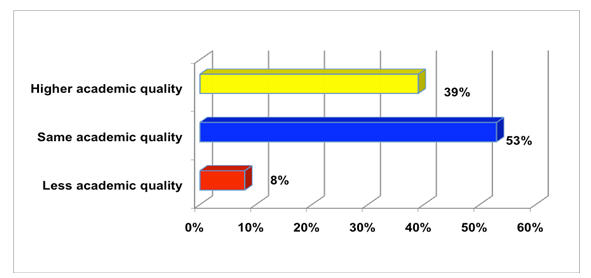

Students stated that the MSHE Program offers the

same (53%) or higher academic (39%) quality courses

than on-campus programs in which they had attended

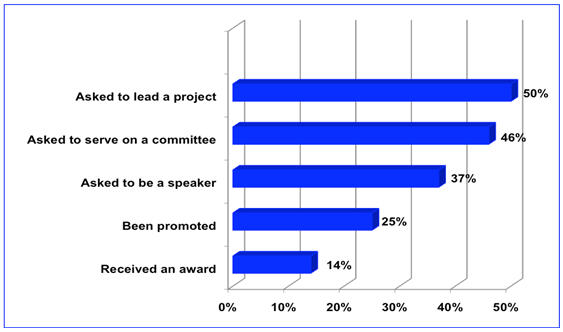

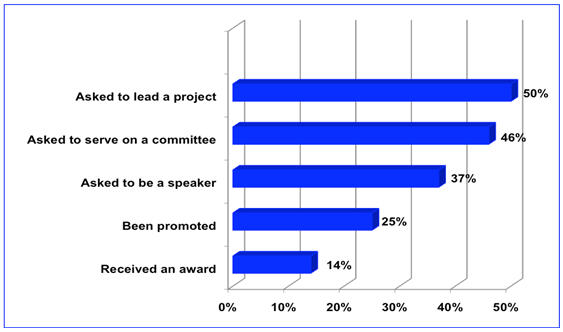

(see Figure 2). One quarter (25%) of the students

stated they had been promoted since enrolling in the

MSHE Program. Additionally, over one-third to half

of the students stated they have been asked to be a

speaker (37%), asked to serve on a committee (46%),

asked to lead a project (50%), and have received an

award (14%) since enrolling in the MSHE Program (see

Figure 3).

Almost all of the students (96%) stated they would

recommend the MSHE Program to individuals seeking to

advance their career in higher education.

Additionally, 92% stated they would recommend the

MSHE Program to individuals seeking to transition

into higher education.

Table 4. Rate the level of importance of each item to your overall

master’s degree experience.

|

|

Important |

Very important |

Total |

|

Quality of instruction |

22% |

78% |

100% |

|

Academic rigor of courses |

42% |

58% |

100% |

|

Academic support from faculty and adjuncts

|

26% |

73% |

99% |

|

Accessibility to faculty and adjuncts |

38% |

56% |

94% |

|

Technical Support |

34% |

59% |

93% |

|

Quality of academic advising |

44% |

45% |

89% |

|

Accessibility to academic advisor |

49% |

40% |

89% |

|

Opportunities to connect with faculty and

adjunct |

43% |

44% |

87% |

|

Opportunities to professionally network |

44% |

41% |

85% |

|

Opportunities to connect with students in the

MSHE Program |

40% |

43% |

83% |

|

Accessibility to library resources |

38% |

44% |

82% |

|

Student Support Services |

43% |

26% |

69% |

|

Feeling connected to Drexel University |

41% |

28% |

69% |

Likert scale: Very important, Important, Neutral,

Not very important, Not important at all

Table 5.

Prior

to enrolling in the MSHE Program, how would you rate

your previous skills in the following areas? and

Since enrolling in the MSHE Program, how would you

rate your current skills in the following

areas?

|

|

|

NA |

Very weak |

Weak |

Moderate |

Strong |

Very Strong |

Strong & Very Strong |

|

Writing |

Previous skills |

0% |

1% |

3% |

25% |

41% |

30% |

71% |

|

Current skills |

0% |

1% |

0% |

11% |

43% |

45% |

88%

(+17%) |

|

Online communications (email, text chat rooms) |

Previous skills |

0% |

1% |

1% |

19% |

35% |

44% |

79%

|

|

Current skills |

0% |

0% |

0% |

7% |

39% |

54% |

93%

(+14%) |

|

Oral communication (audio/voice boards,

presentations) |

Previous skills |

0% |

0% |

3% |

22% |

57% |

18% |

75% |

|

Current skills |

0% |

0% |

0% |

15% |

53% |

32% |

85%

(+10%) |

|

Conducting research (i.e., SWOT analysis,

environmental scan, literature review, etc.) |

Previous skills |

4% |

1% |

19% |

36% |

25% |

15% |

40% |

|

Current skills |

3% |

0% |

4% |

18% |

48% |

27% |

75%

(+35%) |

|

Working in groups |

Previous skills |

0% |

0% |

1% |

27% |

47% |

25% |

72% |

|

Current skills |

0% |

0% |

3% |

14% |

44% |

39% |

83%

(+11%) |

|

Serving as a leader |

Previous skills |

0% |

0% |

8% |

27% |

39% |

26% |

65% |

|

Current skills |

0% |

1% |

1% |

11% |

52% |

35% |

87%

(+22%) |

|

Decision making |

Previous skills |

0% |

0% |

0% |

23% |

52% |

25% |

77% |

|

Current skills |

0% |

0% |

0% |

14% |

51% |

35% |

86%

(+9) |

|

Developing PowerPoint (PPT) Presentations |

Previous skills |

0% |

6% |

10% |

27% |

41% |

16% |

57% |

|

Current skills |

0% |

1% |

0% |

11% |

52% |

36% |

88%

(+31%) |

|

Delivering PPT Presentations |

Previous skills |

0% |

4% |

11% |

40% |

28% |

17% |

45% |

|

Current skills |

0% |

1% |

0% |

19% |

44% |

36% |

80%

(+45%) |

Figure 2. Question:

How does the academic quality of the online MSHE

courses compare to

on-campus programs you have attended?

|

|

Figure 3. Question:

Since enrolling in the Higher Education Program,

identify how you have been

recognized professionally by the institution or

organization where you are employed?

Course Evaluations

The OHT concept integrates student and faculty

interaction into course design to increase learning

and satisfaction. Therefore, it is important to

review course evaluations as a measurement for

student engagement and satisfaction on a quarterly

basis. Two course evaluations from winter 2008 are

provided in Table 6. The evaluations include eight

questions using a 5-point Likert scale (Outstanding,

Above Average, Average, Below Average, and

Unacceptable). The evaluations from both courses

indicate high levels of course satisfaction.

However, it is recognized that the evaluation

instrument does not provide robust feedback with

specific indicators to overall engagement,

assignments, and learning outcomes.

Table 6. Course Evaluations for Winter 2008

|

|

EDHE 606: Higher Education Graduate Co-op |

EDHE 715: Higher Education

Career Development |

|

Rigor of the course |

88% Outstanding

12% Above Average |

83% Outstanding

17% Above Average |

|

Stimulation of my thinking |

88% Outstanding

12% Above Average |

83% Outstanding

17% Above Average |

|

Teaching Method |

88% Outstanding

12% Above Average |

83% Outstanding

17% Above Average |

|

Instructor’s Knowledge |

88% Outstanding

12% Above Average |

100% Outstanding |

|

Support and Feedback |

88% Outstanding

12% Above Average |

100% Outstanding |

|

Value of Course |

71% Outstanding

29% Above Average |

67% Outstanding

33% Above Average |

|

Overall Rating of Course |

79% Outstanding

21% Above Average |

67% Outstanding

33% Above Average |

|

Overall Rating of Instructor |

100% Outstanding

|

85% Outstanding

15% Above Average |

Note: While the samples for the evaluations are

small, the MSHE Program typically does not have more

than 20-25 students in an online course and less

than 20 students in specialization courses in its

commitment to support community development.

Response rates for EDHE 715 was 64% (7 /11 students)

and EDHE 606 was 50% (6/12 students).

It should be noted that MSHE course evaluations were

outsourced from fall 2005 to winter 2008. During

this time course evaluations were modified several

times providing distinct challenges for

benchmarking. In 2007/08, three of the four quarters

had different course evaluations which provided very

limited comparative data. However, course

evaluations will be brought in house to the

School of Education in June 2008. Recognizing the

importance of data driven decision-making, the MSHE

Program has utilized other types of formative and

summative data for data driven decision-making.

Reflective Papers and Journals

Reflective papers and journals provide qualitative

feedback on engagement and learning. Sample feedback

collected from reflective papers in EDHE 606: Higher

Education Career Development and reflective journals

in EDHE 715: Higher Education Career Development are

provided in Tables 7 and 8. The overwhelming

positive comments relating to engagement,

self-esteem, and the acquisition of skills highlight

the positive impact of OHT instruction and

programming.

In EDHE 606, students are required to develop

ePortfolios, apply for an real position

posted in the Chronicle of Higher Education but send

the application to Drexel’s Steinbright Career

Development Center. They then participate in a Live

Mock Interview with a search committee as described

previously. In EDHE 715-716, students participate in

a 20-week Higher Education Graduate Co-op. The Co-op

requires students to develop and lead an action

research project based on an actual

problem within their place of employment. The

faculty who teach EDHE 715/716 also serve as mentors

for the students on these projects. As part of the

course, students are required to submit reflective

journals every two weeks during the 20-week period.

Furthermore, students are required to submit a full

co-op report that includes five chapters similar to

a master’s thesis or abbreviated doctoral

dissertation.

Table 7. Comments Shared in Reflective Papers from

EDHE 606 (Winter 2008)

|

The Live Classroom Mock Interview helped me

formulate a plan to present my best self

in an interview setting and answer questions

thoroughly yet spontaneously. Receiving feedback

brought to my attention areas where I can

improve my performance in interviews. |

|

The mock interview left me with a greater

understanding of what is expected in the

professional world. I have been on several

interviews in my lifetime and I have to say that

the mock interview helped me better prepare for

future professional endeavors. |

|

The verbal responses from the faculty were

beneficial because they allowed me to receive

criticism, positive feedback, and they also

allowed me to further understand the point of

view of others. In the future, I will be more

responsive to others and will use verbal

responses as a means to communicate with my

professional peers and colleagues. It was also

easier to comprehend points made by faculty when

hearing their verbal response versus having to

try to figure out their point of view through

writing. |

|

The higher education career

development course was filled with practical

information that one could utilize in his or her

career. The most valuable experience for me was

the e-Portfolio experience because all the

documentation was electronic, the required

documentation was of practical relevance, and

the follow-up mock interview and feedback helped

identify strengths and weaknesses in this

process. |

|

Due to my experience in this course, I know that

I will be a great leader. I believe that

leadership is the ability to assist others in

reaching their goals and setting an example of

how to be a leader simultaneously. |

Conclusion

The OHT instruction and programming conceptual

framework builds upon five areas of research:

student engagement, community development,

personalized communication, work-integrated

learning, and data driven decision-making. This

dynamic and evolving concept provides students with

a personalized educational experience that brings

the campus to the online environment. Data and

feedback collected over the past three years in the

MSHE Program at Drexel University indicates that OHT

instruction and programming positively affects

student engagement, connectivity, and retention.

Online students seek strong academic programs that

offer opportunities for personal interaction. This

is illustrated by MSHE students placing a high level

of importance on the quality of instruction and

academic rigor of courses while also placing a high

level of importance on their personal interaction

and engagement with faculty, adjuncts, academic

advisors, and students. Additionally, MSHE data

reveals that OHT strategies that emphasize frequent

and quality personal interaction influence student

connectivity to an online program.

Online education offers extensive opportunities for

students to acquire new skills and knowledge from

courses through work-integrated learning. While most

students in online programs do not come to campus,

MSHE data indicates that students can greatly

augment professional skills through OHT instruction

and programming. The integration of practice-based

assignments and reflective learning personalize the

educational experience for students as well as

prepare students for promotion, to serve as

speakers, to lead projects, and to serve on

committees.

Lastly, community development is important for

building and fostering a lifelong connection between

the university and online students. The OHT concept

emphasizes the importance of student engagement

across academic and social communities since this

has an affect on the overall student experience.

Since many online students will never step foot on

campus, interaction may be limited to the online

classroom. Therefore, community development must go

beyond the online classroom and engage students

across all cohorts to extend networking

opportunities and support ongoing student-campus

connectivity.

Table 8. Comments Shared in Reflective Papers from

EDHE 715-716 (Winter & Spring 2008)

|

As we are approaching the end of this term, I

look back at the work done and the

accomplishments up to date. This term was very

challenging but also very rewarding. I see how

the hard work is shaping into a co-op project

that will help me grow in my current position,

develop my knowledge to help me further in my

career, and will add to the literature. The

support and help from the professor was

extremely helpful in giving me direction. Her

feedback and suggestions kept me on track with

the project. I understand the importance of

having an advisor that provides feedback and

direction. |

|

Since my last journal entry, I have received

feedback from the professor on my Literature

Review. I invested a lot of sweat equity

in writing my review, and was not sure I was on

the right track, so hearing that it was well

done and that I should be so proud of my work,

was a HUGE boost to my ego and my confidence.

It also provided some incentive to soldier on

with this project. |

|

Overall, I feel that the research project helped

me to not only learn how to do research but also

will help my program in a very positive way.

Although I work, on a daily basis, with many of

the issues surrounding the functioning of the

program, the research project provided me with

deeper insight on how to make curriculum

development more effective. Examination through

SWOT analysis, environmental scan, and gathering

student data helped me to gain important

information that can help guide our program for

success in the future. While my co-op research

project will be ending soon, I plan to continue

to implement the recommendations that were

developed through the data that was gathered

through this valuable research. |

|

Since the last journal entry, I've received

helpful feedback on my literature review from a

classmate and the professor. I need to

incorporate suggestions into my final document

before this month ends.

Finally, I've noticed that my experience in this

co-op, and especially in this higher education

program generally, has made profound positive

contributions to my new job. This happens both

in what I know and how I express it. |

|

My professor has looked at numerous drafts of my

Capstone project, and always provided me with

great feedback. It is actually amusing in one

regard because a colleague of mine is in a

masters program and she received a paper back

from her professor and there were very few

comments. I asked her where the comments from

the professor were. I am so used to receiving

such constructive and rich feedback, that if I

do not receive that on a project, they must have

not read it. Another thing I have learned is

that feedback is good, and to take it and

improve upon the project at hand. |

|

It is an extraordinarily valuable experience. It

is an exercise in what I've done in the HE

program to day. It is training for future work

assignments when I may be able to follow a

similar project. After this, I'm also interested

in finishing my doctorate in the future. |

|

The entire Drexel online experience has been one

I would never exchange. I was skeptical, and

hesitant, at first about earning this degree

completely online. In comparing this program to

that of my peers at other institutions, however,

I feel as if I went through a higher ed program

that was more challenging and more engaging than

theirs, despite the distance in proximity. |

Recommendations

The OHT concept can be integrated into online and

hybrid/blended programs. However, the implementation

of the concept must be supported by standards and

guidelines for faculty, adjuncts, academic advisors,

and staff. Furthermore, data driven decision-making

is quintessential for the sustainability of the OHT

instruction and programming. Data and feedback on

OHT strategies must be collected as part of an

evaluation process to monitor affects on student

engagement, connectivity, and retention.

Since the development and implementation of the OHT

instruction and programming concept into the MSHE

Program in fall 2005, the results include continued

student growth, financial sustainability, high

student retention rates, active alumni

participation, and national recognition. However,

continued research is needed as the OHT concept

evolves. Furthermore, comparative research with

hybrid/blended and on-campus programs is recommended

to expand the OHT literature.

References

Allen, E. & Seaman, J. (2007). Online nation: Five

years of growth in online learning. The Sloan

Consortium. Babson Survey Research Group. Retrieved

April 20, 2008, from

http://www.sloanc.org/publications/survey/pdf/online_nation.pdf

Astin, A. W. (1975). Preventing students from

dropping out. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Astin, A.W. (1984). Student involvement: A

developmental theory for higher education.

Journal of College Student Personnel, 24 (4),

297-308.

Angelino, L. M., Williams, F. K., & Natvig, D.

(2007). Strategies to engage online students and

reduce attrition rates. The Journal of Educators

Online, 4 (2),1-14. Retrieved

May 6, 2008,

from

www.thejeo.com/Volume4Number2/Angelino%20Final.pdf

Bathe, J. (2001). Love it, hate it, or don’t

care: Views on online learning. ERIC database.

ERIC Document Number ED463805.

Boud, D. (1991). Implementing student

self-assessment. Campbelltown, New South Wales:

The Higher Education Research and Development Society

of Australasia (HERDSA).

Carr, S. (2000). As distance education comes of age,

the challenge is keeping the students. The

Chronicle of Higher Education, 23, A39 .

Retrieved May 20, 2008, from

http://chronicle.com/free/v46/i23/23a00101.htm

Chickering, A. W. & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven

principles for good practice in undergraduate

education." AAHE Bulletin, 39 (7), 3-7.

Cranton, A. & Legge, L. H. (1978). Program

evaluation in higher Education.

The Journal of Higher Education,

49 (5), 464-471. Ohio State University Press.

Dagger, D. & Wade, V. P. (2004) Evaluation of

adaptive course construction toolkit (ACCT).

Retrieved May 5, 2008, from

http://wwwis.win.tue.nl/~acristea/AAAEH05/papers/6a3eh_daggerd_IOS_format_v1.1.pdf

Diaz, D. P. (2002). Online drop rates revisited.

The Technology Source. Retrieved April 10, 2008,

from

http://technologysource.org/article/online_drop_rates_revisited/

Faharani, G.O. (2003). Existence and importance of

online interaction (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia

Polytechnic Institute, 2003). Retrieved May 8, 2008,

from

http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-04232003

202143/unrestricted/Gohar-Farahani-Dissertation.pdf

Flood, J. (2002) Read all about it: online learning

facing 80% attrition rates, Turkish Online

Journal of Distance Education, 3 (2). Retrieved

May 15, 2008, from

http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/tojde6/articles/jim2.htm

Frankola, K. (2001). Why online learners drop out.

Workforce, 80, 53-58.

International Customer Management Institute (2008).

ICMI’s Queue Tips. Retrieved May 12, 2008, from

http://www.icmi.com/WebModules/QueueTips/Question.aspx?ID=182

Johnson, J. (2001). Learning communities and special

efforts in the retention of university students:

What works, what doesn't, and is the return worth

the investment? Journal of College Student

Retention: Research, Theory and Practice, 2 (3),

219-238. Retrieved May 1, 2008, from

http://baywood.metapress.com/app/home/contribution.asp?referrer=parent&backto=issue,4,6;journal,29,35;linkingpublicationresults,1:300319,1

Knapp, L., Kelly-Reid, J., Ginder, S., & Miller, E.

(2008). Enrollment in postsecondary institutions,

fall 2006; Graduation rates, 2000 & 2003 cohorts;

and financial statistics, fiscal year 2006. National

Center for Educational Statistics. U.S. Department

of Education. Washington, DC. Retrieved July 9,

2008, from

http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2008/2008173.pdf

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning:

Experience as the source of learning and

development, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey:

Prentice Hall.

Kolb, D. A. & Fry, R. E. (1975). Toward an applied

theory of experiential Learning. In Cooper, C.

(Ed), Theories of group processes. London:

Wiley Press.

Kruger, J., Epley, N., Parker, J., & Ng, Z. (2005).

Egocentrism over email: Can we communicate as well

as we think? Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 89, 925-936.Retrieved May 9,

2008, from

http://faculty.chicagogsb.edu/nicholas.epley/html/publications.html

Kuh, G. D. (2003). What we’re learning about student engagement

from NSSE. Change, 35 (2), 24-32.

Retrieved

May 10, 2008, from

http://cpr.iub.edu/uploads/Kuh (2003) What We're

Learning About Student Engagement From NSSE.pdf

Leubddorf, B. (2006). Boomers' retirement may create

talent squeeze. The Chronicle of Higher Education,