|

Introduction

Much has been done in the way of studying the trends

of on-campus cheating. There have been thorough

examinations of those who cheat and the methods that

they employ. Significantly less research has been

done on cheating methods and trends in online

education. The recent emphasis on online student

authentication has generated a discussion about

academic integrity within the university distance

education community. The role of technology in

cheating, as well as cheating tendencies in online

courses, is beginning to be investigated.

Longitudinal research shows cheating, in general,

has been an ongoing problem within academia (McCabe,

Treviño, & Butterfield, 2001). With the advancement

of technology come both educational opportunities

and obstacles for students and faculty members.

Educational opportunities include distance education

programs that provide an alternative to the

traditional classroom for students needing

flexibility, and a seemingly endless supply of

resources and information. Educational obstacles are

found in the form of advanced electronic gadgets

that could double as cheating tools, the blurred

line between acceptable and unacceptable study

practices such as approved group study versus

unapproved collaboration, and the increasing

occurrence of cut-and-paste Internet plagiarism.

This paper discusses two studies done within the

University of

Texas System.

Researchers investigated the beliefs of faculty

members who teach both online and on-campus. These

experienced faculty members were asked to compare

opportunities for and the likelihood of student

cheating in online and on-campus courses, along with

the ability to implement each of three approaches to

encouraging academic integrity: the virtue,

prevention, and policing approaches (Hinman, 2002;

Olt 2002).

This research was done on behalf of the UT

TeleCampus (UTTC), the distance education utility

for the

University of

Texas System.

Launched in 1998, UTTC has facilitated more than

65,000 enrollments and has a course inventory that

contains approximately 330 courses (UT TeleCampus,

2008).

The proposed 2006 Higher Education Opportunity Act (Boehner,

2006), included a requirement that accreditors

assure that any institution offering distance

education programs has “processes by which it

establishes that the student who registers in a

distance education course or program is the same

student who participates, completes academic work

and receives academic credit.” This requirement

inspired the staff at UTTC to begin looking at ways

to encourage academic integrity within the courses

offered by the 15 campuses within the UT System via

UTTC. This effort was timely as the proposed

legislation was recently passed and will go into

effect in July 2010 (Epper, Gilcher, McNabb, &

Lokken, 2008).

Gallant proposes the following five categories of academic

dishonesty, stating that these “terms

transcend group boundaries and roles” (Gallant,

2008, p. 10):

1.

“Plagiarism—using another’s words or ideas without

appropriate attribution or without following

citation conventions;

2.

Fabrication—making up data, results, information, or

numbers, and recording and reporting them;

3.

Falsification—manipulating research, data, or results

to inaccurately portray information in reports

(research, financial, or other) or academic

assignments;

4.

Misrepresentation—falsely representing oneself,

efforts, or abilities; and,

5.

Misbehavior—acting in ways that are not overtly

misconduct but are counter to prevailing behavioral

expectations.”

It

is important to note that only one category,

Misrepresentation, is addressed if the emphasis of

an academic integrity effort is focused solely on

student authentication. Instead, UTTC staff members

wanted to consider the issue of academic integrity

and how to encourage it more broadly. This led them

to inquire about the beliefs of the faculty members

teaching online through UTTC, as well as a desire to

develop resources and recommendations for faculty

members wanting to integrate academic integrity

efforts within their curriculum.

Literature Survey

Academic Integrity in Higher Education

Bill Bowers conducted the first published

large-scale study on student cheating in 1964, and

reported that three-fourths of higher education

students engaged in cheating (McCabe et al., 2001).

Thirty years later, similar studies were conducted.

These later studies indicated no significant

increase in the amount of overall cheating (McCabe

et al., 2001; Brown & Emmet, 2001). The researchers

did identify increases in cheating on tests and

exams, but no significant differences in regards to

written assignments (McCabe et al., 2001).

One suggested reason for the long-term consistency in

self-reported cheating on written assignments is the

change in perception of plagiarism by students. For

example, many students today do not recognize

un-cited paraphrasing as plagiarism (McCabe et al.,

2001), nor may they recognize information taken from

the Internet as intellectual property needing to be

cited (Lee, 2003).

Another area in which the line between right and wrong has

been blurred in the minds of students is that of

collusion. This is indicated by the substantial

increase in self-reports of unpermitted

collaboration from 11% of students surveyed by

Bowers, to 49% in 1993 (McCabe, 2005).

Hinman (2005) reported that students typically fall into one

of three categories of behaviors and values. The

first group, students who never cheat, needs a

campus culture that supports their values. On the

opposite end of the spectrum are chronic cheaters,

for whom preventive measures should be in place.

These students require that a campus community be

ever vigilant in its attempts to prevent cheating

and catch cheaters. The third group, those who

occasionally cheat, are the students whose behavior

is most likely to be impacted by campus and faculty

efforts to encourage academic honesty. Hinman writes

that this group—students who sometimes cheat—are the

ones most likely to be affected by the ease with

which students can cheat with the aid of educational

technologies.

Technology and Academic Integrity

Technology and the Internet can both facilitate

cheating. Students taking online exams can benefit

from collaborating with others, access to resources,

and the ability to have someone take an assessment

on their behalf (Eplion & Keefe, 2007). Students

plagiarizing assignments can buy papers from paper

mills or get content for free from digital

libraries, online journals and reference materials,

or online news (Sterngold, 2004).

There is evidence that, although cheating is not on the rise,

cheating with technology is increasing. In 2005,

McCabe wrote that campus administrators had growing

concerns about Internet plagiarism. Only 10% of

students reported participating in cut-and-paste

Internet plagiarism in 1999 (McCabe, 2005). By 2005,

this number rose considerably to 41%.

Academic Integrity and Online Education

While many studies have been conducted to determine

the state of cheating in traditional courses, few

have focused solely on online classes. Many believe

that an online class lends itself more easily to

cheating due to the lack of face-to-face contact

between the students and instructor. Researchers

have indicated, however, that the reasons given for

cheating are not different for the two delivery

methods. Varvel (2005, p. 2) concluded, “no evidence

currently is found to support that a student is more

likely to cheat online.”

In

an effort to determine whether cheating is more

prevalent in online classes, as opposed to

on-campus, a study was performed in 2002 in which

796 undergraduate online students completed surveys

regarding their experience in their online courses.

The results of the survey showed that the level of

cheating in an online course was consistent with

that of an on-campus class during a single semester

(Grijalva, Nowell, & Kerkvliet, 2006). The

researchers’ conclusion supports Varvel when

stating, “as online education expands, there is no

reason to suspect that academic dishonesty will

become more common” (Grijalva, et al., 2006, p.

184).

On

the other hand, there is a shared perception among

many students and faculty members that it is easier

to cheat in an online environment than in an

on-campus class. In a recent study, both groups were

asked about the ease of cheating when learning

online. Results indicated that the majority of both

students and faculty members believed that an online

environment was more conducive to cheating.

Noteworthy, however, is that the majority of

students and faculty members surveyed had never been

involved in an online course. Of those who had taken

or taught an online course, the percentage that

believed it easier to cheat was reduced (Kennedy,

Nowak, Raghuraman, Thomas, & Davis, 2000).

The

Center for Academic Integrity (1999) in its report,

“Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity,” proposes

a definition of institutional academic integrity

that encompasses honesty, trust, fairness, respect,

and responsibility:

“An

academic community of integrity advances the quest

for truth and knowledge by requiring intellectual

and personal honesty in learning, teaching,

research, and service (p. 5); fosters a climate of

mutual trust, encourages the free exchange of ideas,

and enables all to reach their highest potential (p.

6); establishes clear standards, practices and

procedures and expects fairness in the interactions

of students, faculty and administrators (p. 7);

recognizes the participatory nature of the learning

process and honors and respects a wide range of

opinions and ideas (p. 8); and, upholds personal

accountability and depends upon action in the face

of wrongdoing” (p. 9).

A

useful approach for addressing academic integrity

was outlined by Hinman (2002) and applied to online

education by Olt (2002). This three-part effort

includes the policing, prevention, and virtue

approaches. The goal of the policing approach is to

catch and punish students engaging in academic

dishonesty. The prevention approach’s goal is to

limit opportunities for student cheating as well as

the pressure to cheat. The goal of the virtue

approach is to encourage students to strive for

academic excellence and integrity.

UTTC Research Study

Using the Center for Academic Integrity’s definition

of academic integrity and Hinman’s (2002) three-part

approach as a framework, this study presents the

results of an examination of the beliefs of faculty

members regarding academic integrity in online

courses, and ways in which faculty members have

successfully developed communities of integrity in

online courses. The questions were approached

through two research sub-projects, one quantitative

on faculty beliefs and one qualitative on ways to

develop communities of integrity.

The

research questions were as follows: (a) How do

faculty members perceive the differences between the

likelihood of and opportunities for students to

cheat in online courses as compared to on-campus

courses?; (b) How do faculty members perceive the

ease with which the policing, prevention, and virtue

approaches can be implemented in online courses as

compared to on-campus courses?; and (c) What are

ways in which faculty members are successfully

creating communities of integrity in online courses?

Faculty Member Beliefs

Methodology

Invitations to participate in a survey were sent to

256 faculty members who had taught or were teaching

online via UTTC. Seventy-six surveys, or about 30%,

were completed. The UTTC faculty survey investigated

faculty members’ beliefs about the behaviors of

undergraduate and graduate students in on-campus and

online courses. The questionnaire asked the UTTC

faculty members about the likelihood of UT System

students participating in academic dishonesty.

Faculty members were also asked to compare on-campus

and online courses in relation to: (a) the

likelihood that students will cheat; (b) the ease

with which students can cheat; and (c) the ability

to police cheating, prevent cheating, and create

communities in which students do not want to cheat

(the virtue approach).

Results

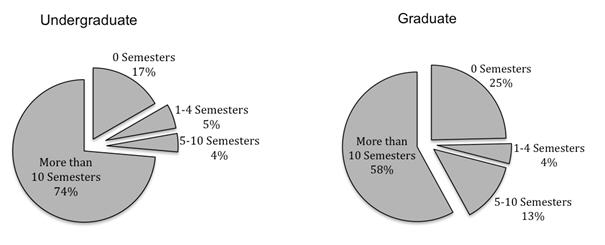

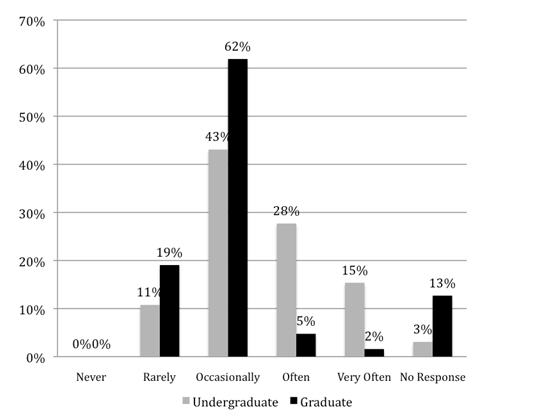

Overall, 83% of respondents had experience teaching

on-campus undergraduate courses and approximately

three-quarters had experience teaching graduate

courses on-campus. Participants’ experience teaching

on-campus is detailed in Figure 1. A majority of the

faculty members surveyed were very experienced

on-campus educators; about three-quarters reported

more than 10 semesters of experience teaching

undergraduates and 58% had more than 10 semesters of

experience teaching graduate students.

Figure 1. On-campus Teaching Experience of UTTC

Faculty Survey Participants

Figure 1. On-campus Teaching Experience of UTTC

Faculty Survey Participants

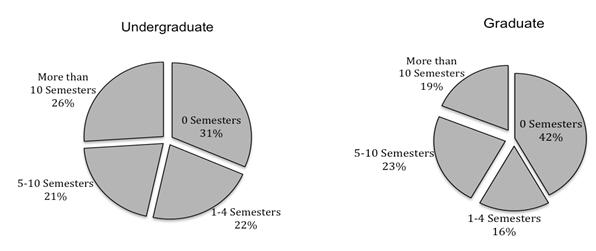

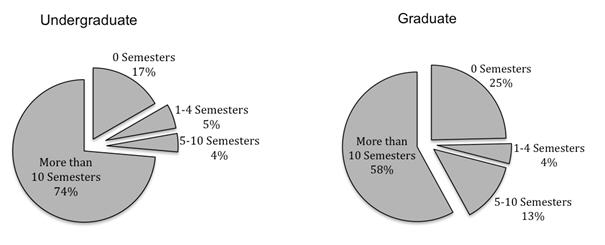

It

is important to note that, as all the survey

participants taught via UTTC, all had online

teaching experience. Specifically, 69% of the

faculty members surveyed had online teaching

experience with undergraduate courses. A smaller but

significant number—58%—of faculty members had the

same experience with graduate courses. Participants’

experience with online teaching is detailed in

Figure 2.

Figure 2. Online Teaching Experience of UTTC Faculty Survey

Participants

Outcomes

Whether the survey question was about the likelihood

of students cheating, the opportunities students

have to cheat, policing cheating, preventing

cheating, or creating communities averse to

cheating, most respondents did not believe that

there was a difference between on-campus and online

courses. Additionally, for every question, the

participants who did not believe that the

environments were the same were most likely to

believe that an on-campus environment is superior to

an online environment.

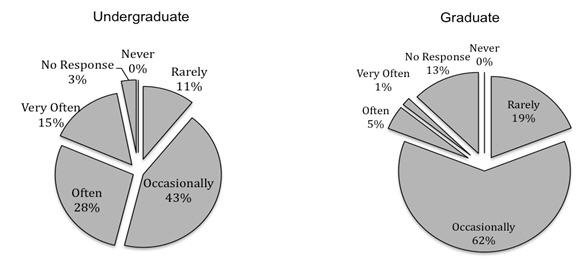

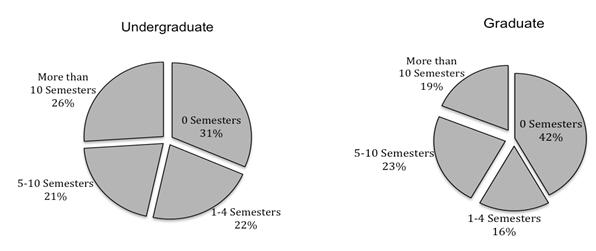

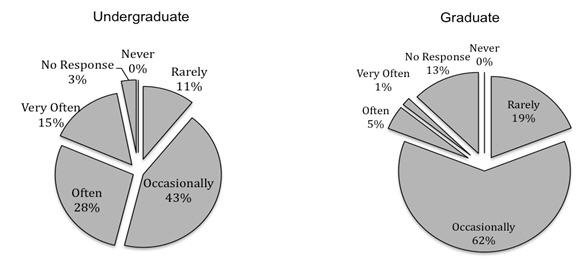

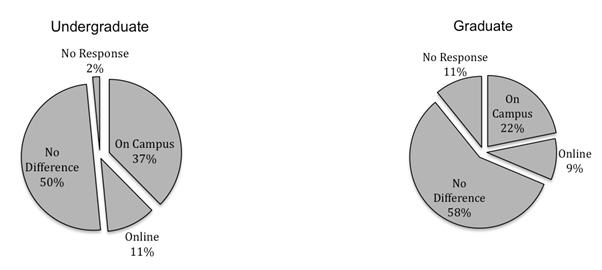

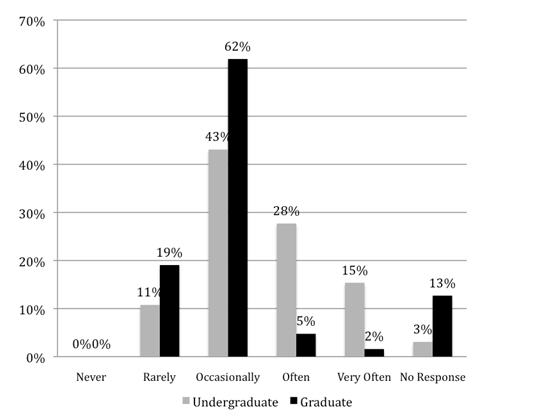

Beliefs regarding the frequency with which students in the UT

System engage in academic dishonesty.

The majority of the faculty members surveyed

believed that students within the UT System—studying

by any medium—engage in academic dishonesty at least

occasionally. More than 60% of the faculty members

surveyed agreed that graduate students cheat

occasionally. On the other hand, a majority of the

faculty members did not agree about their

perceptions of the frequency of cheating among

undergraduate students.

UTTC faculty members were significantly more likely

to believe that undergraduate students participate

in academic dishonesty than they were to believe the

same about graduate students. While 43% of the

faculty members believed that undergraduate students

cheat often or very often, only 6% believed the same

about graduate students. Responses to the question,

“How frequently do you believe students in the UT

System engage in academic dishonesty?” are detailed

in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Faculty Member Beliefs Regarding the

Frequency with which Students in the UT System

Engage in Academic Dishonesty

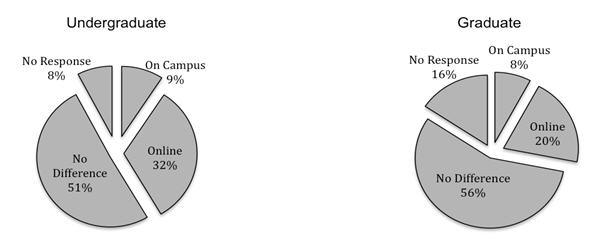

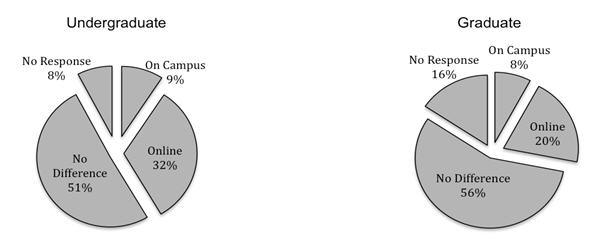

Beliefs regarding opportunities students have to engage in

academic dishonesty.

Approximately one-half of the faculty members

surveyed believed that opportunities for

undergraduate students to cheat are equivalent in

on-campus and online courses, and those beliefs

varied little between those about undergraduate as

opposed to graduate students. Nevertheless, many

faculty members did not agree; about one-third

believed that, for undergraduate students, an online

course is most conducive to cheating. Specifics

regarding beliefs about opportunities to cheat in

both on-campus and online courses are shown in

Figure 4.

Figure 4. Faculty Member Beliefs Regarding the

Opportunities Students Have to Engage in

Academic

Dishonesty in Online and On-Campus Courses

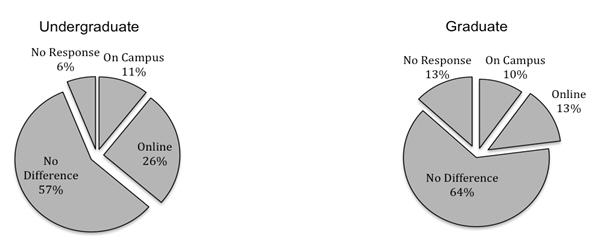

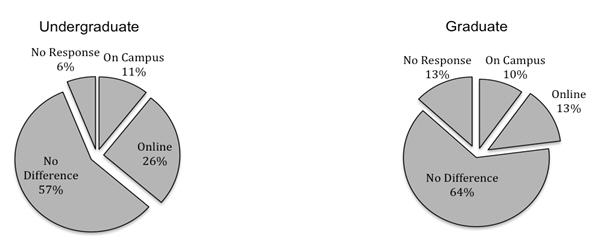

Beliefs regarding the likelihood that students will engage in

academic dishonesty.

When asked about the possibility that students will

engage in academic dishonesty, 57% and 64% of

faculty members saw no difference between the

delivery methods, when teaching undergraduate and

graduate students respectively. Of the faculty

members who did not consider the two methods to be

equivalent, most believed online classes to be

inferior.

This is especially true of faculty perceptions of

undergraduate students; about one-quarter of the

faculty members believed that undergraduates are

most likely to cheat in an online course.

Information on faculty member beliefs regarding the

likelihood that students will cheat is shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 5. Faculty Member Beliefs Regarding the

Likelihood Students will Engage in Academic

Dishonesty in Online and On-Campus Courses

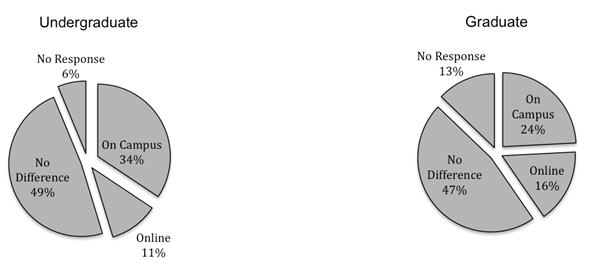

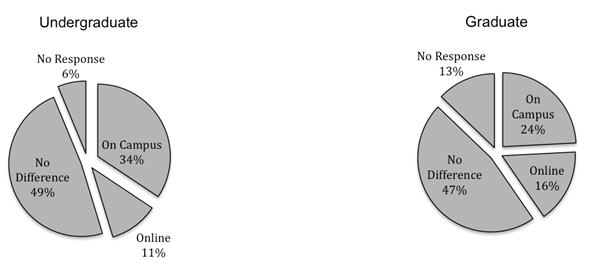

Beliefs regarding the ease with which academic

dishonesty can be identified (the policing approach).

Almost one-half of survey participants believed that

the ability to catch cheaters is the same in either

an on-campus or online course. Other faculty

members—34% for undergraduate and 24% for graduate

courses—thought an on-campus environment is a better venue in which

to identify cheating. A look at beliefs regarding

the effectiveness of the policing approach in

on-campus and online courses is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Faculty Member Beliefs Regarding the Ease

with which Academic Dishonesty can be Indentified

in Online and On-Campus Courses

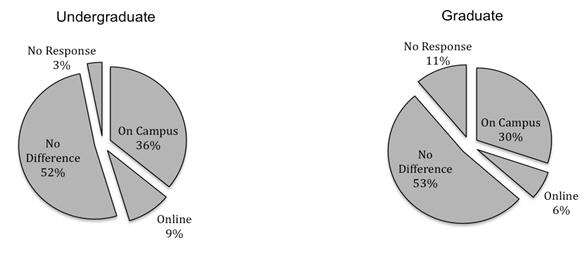

Beliefs regarding the ease with which academic

dishonesty can be prevented (the prevention

approach).

Survey results regarding prevention of cheating are

in Figure 7. Approximately one-half of the faculty

members surveyed believed that it is as easy to

prevent cheating in an online course as it is to

prevent it on-campus. Nevertheless, approximately

one-third thought it was easier to prevent cheating

in an on-campus course.

Figure 7. Faculty Member Beliefs Regarding the Ease

with which Academic Dishonesty can be Prevented

in Online and On-Campus Courses

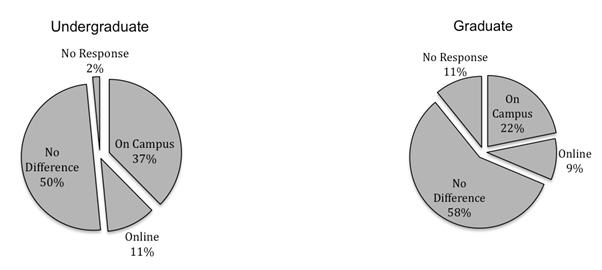

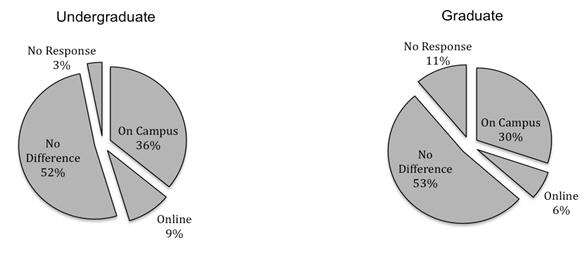

Beliefs regarding the ease with which a community of

integrity can be created (the virtue approach). One-half of the faculty members believed that there is no difference between an

on-campus and online course when creating an

academic community of integrity in an undergraduate

course and slightly more had the same confidence

about the delivery methods when teaching graduate

courses. Nevertheless, a significant number—37%—felt

that an on-campus course is best for creating a

community of integrity with undergraduate students,

and 22% percent indicated the same belief about

graduate students. A look at beliefs regarding the

ability to create communities of integrity in

on-campus and online courses is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.Faculty Member Beliefs Regarding the Ease

with which a Community of Integrity can be Created

in Online and On-Campus Courses

To summarize the responses to questions about the

policing, prevention, and virtue approaches, about

one-half of faculty member respondents thought that

any of the three approaches are equally likely to be

effective in either type of course, however a

significant number of faculty members had concerns

about online courses. This is especially true when

teaching undergraduate students; about one-third of

the faculty members believed that an on-campus

course is more effective in implementing any of the

three approaches with undergraduate students.

Developing Communities of Integrity

Methodology

Using the Center for Academic Integrity’s definition

of a community of integrity, a one-question survey

was developed in which participants were asked to

share an idea for creating a community of integrity

in an online course. This anonymous survey was

announced on listservs frequented by faculty and

staff members involved in online education.

Fifty-nine individuals responded. The research team

reviewed the responses from the online survey and

grouped like ideas together, forming six categories.

Two focus groups were held in which each group of

participants was asked to review half of the

categories and rank the ideas presented. The focus

group participants consisted of faculty and staff

members involved in online education. They

represented eight academic campuses and four medical

branches within the UT System.

Results

Input from the focus group discussions regarding the

presented ideas were analyzed for commonalities.

Three distinct themes emerged from the discussions

into which the ideas were grouped, namely design,

communication, and collaboration. The rankings of

the presented ideas were tallied and prioritized.

The twelve ideas with the highest ranking were

selected, with each of the three established themes

being represented.

Outcomes

Below is a summary of the focus group findings for

each of the three categories, along with the twelve

corresponding ideas generated.

Course, assignment, and assessment design.

Focus group participants believed that some

assignment and test designs lend themselves to

cheating more than others. In addition, a faculty

member can design tasks that challenge and interest

students, require team collaboration, and provide

opportunities for students to contribute on a

personal level, all of which facilitate student

honesty. Participants also believed that a clear

understanding of the grading criteria, in the form

of a rubric, helps students comprehend the level and

type of participation needed in order to succeed. In

other words, taking away the guesswork allows

students to focus more on learning and less on the

mystery of achieving the desired grade. Following

are the top responses within the area of design:

-

Incorporate critical thinking discussions into online

classes, allowing students to contribute their

experiences, successes, and problems pertaining to

the topic being discussed.

-

Have assignments and activities in which appropriate

sharing and collaboration is essential to

successful completion.

-

Foster a community of integrity by choosing authentic

learning tasks that require group cohesiveness and

effort. This includes posing authentic questions

for students; creating assignments that are

distinctive, individual, and non-duplicative, or

about what individual students self-identify as

their personal learning needs; and, helping

students turn their attention to exploring an

issue, rather than focusing on grades.

-

Provide rubrics, or detailed grading criteria, for all

assignments at the beginning of the course so that

learners can know and understand how they will be

scored.

Communications with students. Focus group participants identified the most ideas used to

create a community of academic integrity in the area

of communication, making it clear that communication

is an integral component in successfully creating

the community. The focus group participants viewed

successful communication to be the responsibility of

the faculty member, since most of the responses

within this category focus on information provided

by the faculty member to the students, rather than

two-way communication. The top ideas within the

communication category are:

-

Clearly state your expectations for the students as well

as what they should expect from you.

-

Include a statement in the syllabus encouraging honest

work, so that students can contribute their own

unique perspective to the class. This allows

students to understand that differing points of

view enhance the learning experience for everyone.

-

Develop a class honor code and ask students to commit to

it.

-

Provide a definition of academic integrity and cheating.

Clearly explain what is considered dishonest and

unacceptable behavior.

-

Create an awareness of campus policies that include

stating the academic honesty policy within the

online learning environment and discussing it in

the early stages of the course. It is also

important to provide a link to the campus website

on academic integrity.

-

Create an environment where opinions are valued and

grading is unbiased. This welcomes all ideas, and

encourages participation by dispelling fears of

giving an incorrect answer.

Collaboration between students.

While the role of collaboration was believed to be

significant in creating a community of academic

integrity, focus group participants found it to be

the most difficult on which to elaborate. Of the

twelve ideas presented for all three categories,

only two fit into the category of collaboration.

Participants viewed successful collaboration as

involving students as stakeholders in the process of

creating the desired community, as well as valuing

respect for others. The top ideas within the

collaboration category are:

-

At the start of the course, ask students for their input

on how to create a community of integrity. This

establishes the students as stakeholders in the

community through the process of its formation.

-

Require students to acknowledge and further each other’s

work. By respecting the contributions of others

and actively working to help others learn,

students develop a sense of team and ownership.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that faculty

members do not see significant differences in online

and on-campus courses when it comes to academic

integrity. Additionally, the researchers identified

best practices for creating communities of integrity

in online courses, and found that they can be

developed in online classes through means very

similar to those for on-campus courses.

Faculty Member Beliefs Regarding Academic Integrity within

the UT System

The majority of the faculty members surveyed

believed that students within

the UT System engage in academic dishonesty at least

occasionally. Nearly half believed that

undergraduate students cheat either often or very

often. As can be seen in Figure 9, UTTC faculty

members were significantly more likely to believe

that undergraduate students participate in academic

dishonesty than they were to believe the same about

graduate students.

Hard, Conway and Moran found that faculty members'

beliefs about the frequency of student academic

misconduct, “were significantly closer to student

self-reports of academic misconduct” than were

estimated by students (Hard et al., p. 1074). If

UTTC faculty members are equally insightful

regarding their students, cheating by undergraduates

is a considerable problem in both online and

on-campus courses, and extra efforts should be made

to address undergraduate cheating within the UT

System.

Faculty Member Perceptions Regarding Academic Dishonesty in

Online and On-Campus Courses

Regardless of whether they were asked to consider

the opportunities for or the likelihood of cheating,

or the ability to successfully implement one of the

three suggested approaches to developing a community

of integrity (policing, prevention, or virtue) there

was remarkable consistency in the faculty member

responses.

The

most likely response by a faculty member was to

express a belief that there is no difference between

online and on-campus courses when it comes to

academic integrity. At least 50% of faculty members

expressed that belief for each of the five research

areas (likelihood of cheating, opportunities to

cheat, the policing approach, the prevention

approach, and the virtue approach).

Of the faculty members who did not believe online and

on-campus learning environments are equally

effective for creating communities of integrity,

most preferred on-campus courses, especially for

undergraduate students. This belief was consistent

across all issues investigated. Faculty members were

particularly likely to prefer an on-campus course

when implementing the virtue approach.

Figure 9. Comparison of Faculty Member Beliefs

Regarding the Frequency with which Undergraduate

and Graduate Students Engage in Academic Dishonesty

within the UT System

The

number of faculty members who prefer an online

course is small, but not insignificant. Further, in

each of the five research areas, at least 60% of

faculty members believe that an online course is as

effective or more effective than an on-campus course

when encouraging academic integrity.

As

this study only encompassed online educators, it is

difficult to know if the opinions of the faculty

members surveyed are reflective of the entire UT

System. There is some evidence that there are

correlations between experience with teaching online

and beliefs about cheating in online courses (Hard

et al., 2006; Kelley & Bonner, 2005). Additionally,

it is important to note that all the faculty members

surveyed taught via the UT TeleCampus and have

shared experiences such as faculty training, course

quality standards, instructional technologies, and

student and faculty member supports. Therefore, the

faculty members surveyed were a relatively

homogeneous group.

Researchers have detected a predictable cycle

regarding faculty members’ perceptions of cheating

and action taken by them. Hard, Conway, and Moran

(2006) found that faculty members who believe that

cheating is isolated are less likely to engage in

prevention or policing efforts, while Kelley and

Bonner (2005) found that faculty members who

perceive cheating to be pervasive are more likely to

view academic dishonesty to be a serious problem in

their class. If faculty member beliefs drive similar

actions within the UT System, it would indicate a

strong interest in and motivation to encourage

behaviors of integrity by students, especially in

undergraduate courses where the perceived level of

academic dishonesty is highest.

The

results of this study suggest that levels and types

of academic dishonesty are similar in an online

environment to that found on-campus, and that

successful efforts to encourage integrity are

similar regardless of whether the course is online

or on-campus. This may indicate that online

classrooms should be integrated into the campus

academic integrity program, rather than separate

programs being created specifically for online

courses.

Additionally, as campuses create policies and

procedures to encourage academic integrity in online

classes, the effectiveness of those efforts may be

undermined by differing opinions regarding cheating

in online classes between faculty members who have

taught online and faculty members and administrators

who do not have experience with online teaching.

This study found that faculty members engaged in

teaching online believed that academic dishonesty is

no different in online and on campus courses. Other

researchers have found that faculty members who do

not teach online believe academic dishonesty is more

likely to occur in an online course (Hard et al.,

2006; Kelley & Bonner, 2005).

There is evidence of awareness that faculty members

teaching online may have opinions about online

classrooms that differ from their peers and others.

When discussing the new student authentication

requirements for online courses, a representative of

the Department of Education noted that while “many

faculty members are confident that they know their

online students as well as or better than students

in their face-to-face classes,” it is important to,

“understand that the congressional delegations are

less clear about what happens in distance education

courses and they are concerned the online

environment provides greater opportunity for

fraudulent behavior” (Epper, et al., 2008). This

discrepancy in opinions is also reflected in studies

conducted within the UT system that found that

administrators are, “more concerned about

controlling academic honesty in Web-based courses

than in the traditional classroom” (Olsen & Hale,

2007).

The

most effective way to determine which of the

prevailing opinions regarding cheating in online

courses within the UT System is correct would be to

determine the cheating behaviors of students in

online classes as compared to on-campus. The

researchers recommend a study aimed at student

perceptions of cheating, in an attempt to verify the

differences, if any, in the degree of self-reported

cheating between online and on-campus courses.

Strategies for Creating Communities of Integrity in Online Courses

There is evidence that the design of an online

course can contribute to any of the three

approaches—policing, prevention, and virtue—and

facilitate academic honesty (Olt, 2002). Studies

also show that students want faculty members to

communicate expectations, focus on learning rather

than grades, and encourage the development of good

character in their classrooms (McCabe & Pavela,

2004). Additionally, research has shown that a

student who perceives that they have a positive

relationship with their instructor is not only more

likely to learn, they are also less likely to cheat

(Stearns, 2001).

The

findings of the UTTC study mirror conclusions from

other researchers (Olt, 2002; McCabe & Pavela,

2004). The three main areas of design,

communication, and collaboration have been shown in

previous studies to be influential in creating

communities of integrity in the classroom. These

same areas were identified as the driving forces

behind the classroom successes of the UTTC faculty

members, as they discussed and ranked the ideas

gleaned from the listserv survey when developing the

list of twelve strategies for creating a community

of integrity.

The

strategies generated in this study for creating an

environment of academic integrity within an online

class are not unique to an online environment but

rather are best practices that can be applied to

both online and on-campus environments. The way in

which assignments and assessments are designed,

students participate in class and interact with one

another, and honest and open communication is

encouraged are effective for both online and

on-campus classes. The researchers believe that the

methods and strategies developed for creating an

environment of academic integrity are useful for

either venue.

The

best practices generated in this study relate to the

area of virtue and creating an environment where

students will not want to teach. The researchers

recommend additional research be conducted to

generate similar best practice lists for the areas

of policing and prevention.

Conclusion

The

results of this study can be expressed with the old

saying: “as much as things change, they stay the

same.” The researchers found that online educators

within the UT System do not see significant

differences between online and on-campus courses

when it comes to academic dishonesty or efforts to

encourage academic integrity.

Additionally, the development of a list of best

practices to encourage communities of integrity in

online courses is a useful tool for faculty members

who are striving to develop learning environments

based on honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and

responsibility. Even though the recommended ways in

which to implement the twelve ideas were intended to

be unique to the online classroom, they are equally

useful in an on-campus course.

|