Introduction

We share cultures through language. In the culture

of Education, for example, there are specific ways

of using language to describe teaching and

learning. This language becomes further

differentiated within the culture of Math

Education or Music Education. In spite of such

differences, a discipline-neutral discourse of

teaching and learning has recently evolved from

the newer field of Instructional Technology where

teaching and learning are typically discussed as

generic. It is the aim of this research to

provide empirical evidence of real differences in

how disciplines conceive of and speak about

teaching and learning.

The wave of change in instructional technology

often pulls together faculty from different

disciplines. Faculty members from as diverse areas

as Engineering and Literature find themselves in

the same instructional design/technology workshops

thinking and talking about teaching and learning

as if these concepts were conceptually and

linguistically shared. This study examines the

underlying conceptual grounding that faculty from

differing disciplines bring to such discussions.

As this kind of interdisciplinary activity grows,

the issue of common language and concepts

regarding instructional practices becomes

increasingly important. We believe that clarifying

similarities and differences between disciplinary

discourses around digital learning objects can

lead to more accurate and rewarding

interdisciplinary conversations regarding

instructional practices overall. We view

evaluation of digital learning objects as

representing a unique venue for 1) examining the

different discourse patterns used by different

discipline communities; and 2) examining

convergences and divergences around teaching and

learning that both exemplify and transcend

disciplinary boundaries

Digital Learning Objects

The term ‘digital learning object’ is a relatively

new one. The term describes pieces of

instructional material typically found on the

internet. To some, “learning objects represent a

completely new conceptual model for the mass of

content used in the context of learning” (Hodgins,

2002, p.1). The development and use of this new

conceptual model can be considered part of the

larger effort on the part of instructional

technology theorists to name

discipline-independent theories of learning.

Contemporary theories of instructional design, for

example, include budding theories on the

composition and sequencing of learning objects

(Wiley, 2000), the metadata they might contain,

and standards for their design (Godwin-Jones,

2004). For others, however, digital

learning objects are merely additional curricular

material at their disposal. A conclusive

definition remains elusive as, at present, any of

the following may fall under the digital learning

object umbrella: lectures, lecture handouts, tests

and quizzes, interactive assignments, images,

slides, cases, models, virtual experiments,

simulations and reference material.

For our

purposes, learning objects are considered to be

“small, reusable chunks of instructional

media” (Wiley,

2000, p.2).

Digital

learning objects are often cataloged in learning

object repositories such as MERLOT (https://merlot.org)

from which our data is drawn.

Disciplinary Discourse

There is ample evidence of systematic variation

between the language used in academic disciplines

(e.g., Biber, Conrad, Reppen, Byrd, & Helt, 2002;

Csomay, 2005). Indeed, the fact of distinctly

different academic disciplines and their

disciplinary discourses has been likened to

tribalism (Bauer, 1990;

Becher, 1989). What contrasts one tribe

from another is the language each speaks as well

as the overall essential epistemologies concerning

the subject area (Table 1). The discourse choices

we make – how we use language within our

disciplines - match the expectations of the

community in which we are accustomed to

communicating (Meskill & Anthony, 2007).

Table 1. Disciplinary Differences

|

Humanities |

Sciences |

|

Evocative |

Analytical |

|

Social construction of knowledge |

Scientific view of truths |

|

Critical |

Empirical |

|

Evaluative |

Objective |

|

Integration |

Simplification through isolation |

In short, disciplinary differences are manifest in

widely varying epistemologies, discipline-specific

discourses, disciplinary traditions of teaching

and learning, and in students’ preferred learning

approaches and styles (Bradbeer, 1999). With

instructional technology activities in higher

education bringing these diverse groups together

to address issues of teaching and learning, one

might conclude that between-discipline

communication would be thus constrained. How do

the disciplines view and talk about their teaching

practices and their students’ learning? German

sociologist Karl Jaspers calls this the “creative

tension” that occurs when people from differing

disciplines, with different discipline-specific

ways of knowing and talking come together

(Jaspers, 1959).

Evaluating Digital Learning Objects

Evaluating digital learning objects “helps in

clarifying audiences and their values, identifying

needs, considering alternative ways to meet needs

(including selecting among various learning

objects), conceptualizing a design, developing

prototypes and actual instructional units with

various combinations of learning objects,

implementing and delivering the instruction,

managing the learning experience, and improving

the evaluation itself” (Williams, 2000, p.1).

Since 1999, the MERLOT repository (https://merlot.org)

has been collecting, curating, and subjecting to

peer review tens of thousands of high quality

digital learning objects from a wide range of

disciplines. The peer review process consists of

two faculty members within the designated

discipline providing numerical ratings and prose

reviews of the digital learning object. A

composite review is then developed by an

appropriate editorial board and posted on the

MERLOT site. This process produces a written,

publicly accessible review, the language of which

is the focus of analysis for this study.

Methodology

For the purposes of this study the archived texts

of 1,691 MERLOT peer reviews were saved as text

files and included in the corpus of one of the

three focal discipline groups: Education,

Humanities or Hard Sciences. The Education group

is comprised of 321 texts that reviewed learning

objects in education. The Humanities group

includes 478 reviews in history, music and world

languages. 892 reviews in biology, chemistry and

physics comprise the Hard Sciences group.

Corpus-based concordancing methodologies (see

Biber, Conrad & Reppen., 2002) were utilized to

capture linguistic characteristics of the

disciplinary discourses. The Concordance software,

developed by R.J.C. Watt

(http://www.concordancesoftware.co.uk),

served as the primary data analysis tool.

The quantitative analysis of data was

complimented by the qualitative study of the

context in which words are utilized in each of the

discipline groups.

The following research questions guided the

analysis of the texts under examination:

-

What are the differences and similarities in

vocabulary choice of reviewers in Education,

Humanities and Hard Sciences? Do disciplines

differ in the frequency and contextual usage of

lexicon items often found in the selected texts?

-

Do there exist any distinct variations in who is

seen as performing the teaching and the learning

with the learning objects being reviewed? Who

is the primary agent (doer) of the instructional

process – the teacher, the student, or the

learning object?

-

Do disciplinary discourses differ in their

syntactical organization?

Finally, through our analyses we wished to probe

the larger question of how corpus-based analysis

of disciplinary discourses might inform the fields

of instructional design, cross-/inter-disciplinary

studies, and/or other fields.

Results

Most Frequent Words

Investigating the frequency of words provides

valuable insight into the language peculiarities

of a given text and enables comparison with other

texts (Biber, Conrad, & Reppen, 2002). For our

initial analysis we first focused on the most

frequent words that occur in texts composed by

reviewers in Education, Humanities and the Hard

Sciences. Table 2 shows the top ten most

frequently used words in each disciplinary group.

Here and later in the article we use “word” to

refer to a lemma, i.e. “ the base form of a

word, disregarding grammatical; changes such as

tense and plurality” (Biber, Conrad, & Reppen,

2002, p.29). Thus in tables and discussions each

word represents a word family where each member is

derived from the same root.

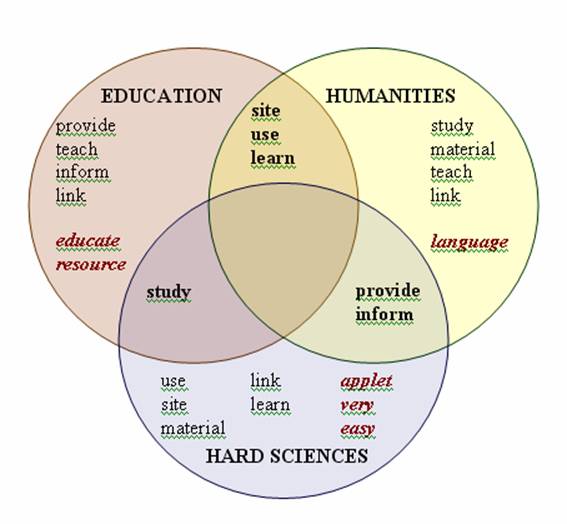

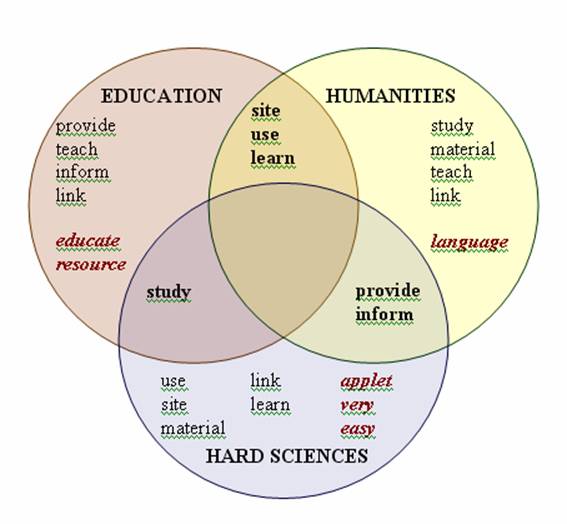

The three disciplinary groups share 7 out of 10

words (70%) from the list of 10 most frequently

used words. Each group also includes one or two

words that are not frequent in the other two

discipline groups (see shaded cells in Table 2 and

italicized words in red ink in Figure 1). Not

surprisingly, reviewers in Education often use

words with the common root educate. Those

in Humanities often talk about languages

and French in particular, which could be

explained by the large number of learning objects

related to language learning and teaching.

Reviewers in the Hard Sciences often use the word

applet to refer to learning objects in

their discipline group. Educators also use the

descriptor resource to describe the

electronic materials, while their colleagues in

the Hard Sciences choose to review learning

objects descriptively utilizing such words as

very and easy.

Sharing individual words, however, does not mean

that disciplines coincide in the whole corpus of

vocabulary used. Z-tests (confidence interval >=

95%, p<=0.05, 2-tailed) revealed statistically

significant differences between the usage of all

shared vocabulary: no word is used at the same

frequency rate in all three discipline groups,

though some words could be used at the same rate

in two disciplines (see Figure 1). For example,

word groups derived from site, use

and learn are used at the same rate in

Education and Humanities; the lemma study

is as common in Education as in the Hard Sciences,

while inform and provide showed no

difference in frequency when Humanities and the

Hard Sciences were compared.

Table 2. Ten Most Frequently Used Words (Lemmas)

in Each Disciplinary Group

|

Education

N=218,731 |

Humanities

N=262,225 |

Hard Sciences

N=436,004 |

|

Site 150 (3281) |

Site 148 (3892) |

Use160 (6998) |

|

Use130 (2837) |

Use 136 (3567) |

Study117 (5110) |

|

Teach 123 (2680) |

Study 105 (2757) |

Site 81 (3548) |

|

Study 121 (2643) |

Learn 73 (1911) |

Applet 64 (2777) |

|

Learn/learner 75 (1637) |

Material 49 (1293) |

Material 42 (1837) |

|

Educate 72 (1575) |

Language 48 (1271) +

French 25 (665) |

Provide 41 (1781) |

|

Provide 59 (1280) |

Teach 47 (1224) |

Link 37 (1600) |

|

Inform 56 (1225) |

Link 45 (1175) |

Learn 32 (1405) |

|

Link 53 (1162) |

Provide 44 (1166)

|

Very 32 (1391) +

Easy 30 (1301) |

|

Resource 50 (1088) |

Inform 31 (823) |

Inform 30 (1311) |

Note:

Frequency per 10,000 words, raw number in

brackets. Shaded are cells that include words

specific for a discipline group.

Figure 1. Most Frequently Used Words: Points of

Convergence and Divergence

Thus, while disciplines may share commonly used

words, when the whole body of vocabulary used in

each discipline is taken into account, we see

differences in frequencies. It seems that it is

the genre of review, as well as the similarity of

objects being analyzed, that make the top 10 list

identical in 7 out of 10 instances. However,

differences in disciplinary discourses surface

when close statistical analysis is carried out.

The Not Too Surprising Category

While the top 10 list mostly consists of words

common to the three disciplines, further analysis

reveals a number of words whose use is unique to

the discipline. Closer examination allowed us to

determine those words that we include in the Not

Too Surprising category (see Table 3). As the

category title indicates, this category consists

of words that one would expect to find in a given

discipline.

Overall, the words belonging to the Not Too

Surprising category can be described as:

-

a primary subject of the discipline (education,

culture, language)

-

an object of study (vocabulary, concept)

-

learning stakeholders (teachers, students

with disabilities)

-

teaching/learning tools (rubric, audio,

applet, animation)

-

ways of presenting and acquiring knowledge (design,

discuss, scaffold, guide, practice,

conceptualize, see, structure).

Table 3 below visually compares these vocabularies

across the three discipline groups. All words

included in the table show statistically

significant differences in the rate at which they

are used by one of the three discipline groups

when compared with the other two groups. Some of

these words are virtually non-existent in the

other disciplines. For example, the word

scaffold seems to be familiar only for

reviewers in Education, while parameter is

used almost exclusively in the Hard Sciences.

These words could be described as professional

jargon. Still, a number of words, though belonging

to the common lexicon, find their home in one

discipline group while being rare guests in

others. These words reveal a unique worldview in

which some phenomena are more valued and more

often talked about than others. This is supported

not only by the high frequency of a lemma in

general, but also by the variety of derivatives

that belong to the same word family. For example,

the lemma culture has 22 derivatives in the

Humanities, 11 derivatives in the Hard Sciences

(including agriculture and horticulture)

and only 8 word family members in Education, which

shows the importance of this concept in the

Humanities.

Table 3. Not Too Surprising Category

|

Words |

Education

N=218,731 |

Humanities

N=262,225 |

Hard Sciences

N=436,004 |

|

disability |

10 (215)* |

0 (1) |

0 (0) |

|

design |

23 (505)* |

18 (481) |

13 (570) |

|

discuss |

14 (310)* |

10 (273) |

8 (363) |

|

educate |

72 (1575)* |

8 (204) |

8 (333) |

|

evaluate |

9 (192)* |

2 (50) |

1 (48) |

|

guide |

13 (284)* |

9 (240) |

6 (281) |

|

rubric |

9 (195)* |

1 (19) |

0.1 (5) |

|

scaffold |

1 (15)* |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

|

teach |

131 (2862)* |

47 (1224) |

14 (629) |

|

audio |

4 (97) |

20 (537)* |

2 (93) |

|

culture |

5 (114) |

31 (802)* |

1 (57) |

|

French |

0 (1) |

25 (665)* |

0 (8) |

|

history |

7 (152) |

31 (800)* |

5 (226) |

|

language |

8 (181) |

48 (1271)* |

3 (146) |

|

music |

1 (28) |

25 (650)* |

0 (14) |

|

practice |

12 (267) |

16 (427)* |

5 (203) |

|

vocabulary |

2 (41) |

17 (448)* |

1 (53) |

|

animate |

3 (71) |

5 (131) |

26 (1114)* |

|

applet |

2 (52) |

5 (124) |

64 (2777)* |

|

concept |

14 (312) |

5 (140) |

26 (1122)* |

|

cover |

3 (75) |

5 (142) |

10 (440)* |

|

interactive |

9 (188) |

11 (289) |

21 (902)* |

|

parameter |

0 (1) |

0 (7) |

8 (341)* |

|

see |

6 (131) |

6 (153) |

12 (530)* |

|

structure |

6 (110) |

5 (121) |

9 (399)* |

|

understand |

21 (468) |

13 (334) |

27 (1191)* |

Note:

Frequency per 10,000 words, raw number in

brackets. Shaded are cells with words that are

more frequent for a specific discipline group.

*Significantly different proportions as compared

to the other two disciplinary groups (confidence

interval >= 95%, p<=0.05,

2-tailed), based on Z-test for two proportions

http://www.dimensionresearch.com/resources/calculators/ztest.html

Thus, the Not Too Surprising category provides

additional evidence that speaks to divergences

among disciplinary discourses. The selection of

words used reveals discipline-specific ways of

speaking about MERLOT digital learning objects

which illustrate significant differences in

disciplinary traditions of teaching and learning.

Descriptors

To further explore discipline-specific lexicons,

we examined descriptors selected based on their

frequency and compared the frequency of words in

two groups: Education vs. the Hard Sciences and

Humanities vs. the Hard Sciences.

The results indicated that out of 89 words

selected, only 8 showed no significant difference

in usage between all three disciplines: easy,

useful, most, particular, visual, major, main,

better.. In 29 instances only one group -

Education or Humanities - showed significant

difference when compared to the Hard Sciences;

these are such descriptors as high, various,

comprehensive, engaging, etc. Judging by the

words selected, in 67% of cases reviewers choose

different descriptors to describe and evaluate

MERLOT learning objects (see Table 4).

The analysis shows that each discipline uses

descriptors that could be included into the Not

Too Surprising category as they represent

adjectives that are particular to the discipline.

For example:

Education = educational, instructional,

professional (development), social, etc.

Humanities = cultural, historical, musical,

grammatical, etc.

Hard Sciences = mathematical, physical,

numerical, quantitative, etc.

Still some frequently used adjectives yield

surprising results. Reviewers in Education, for

example, tend to use the adjective scientific

twice as often as their colleagues in the Hard

Sciences. We might interpret this to be in keeping

with current U.S. federal policy in Education that

stress this term. It is important to note in this

regard that the MERLOT peer reviewers in Education

are all U.S. born native speakers of English.

Another anomalous use of adjectives is in the

Humanities where reviewers use the descriptor

human far less often than their colleagues in

Education and the Hard Sciences.

It is interesting to note that in the Hard

Sciences a wide range of words is used to evaluate

learning objects; notable in that the

stereotypical view of scientists involves their

being less verbal than their Humanities

counterparts. Some of the frequently used

adjectives in the Hard Sciences, such as good,

excellent, nice could be

characterized as subjective evaluation words.

Reviewers in the Hard Sciences more frequently

than other disciplines also use words that

describe objective parameters related to a)

accuracy – accurate/inaccurate, correct, b)

size– small, large, little, and c)

parameters – limited, detailed. Comparative

adjectives – different/similar – are also

frequently employed as are terms that indicate

level of difficulty – introductory, basic,

simple, difficult. The evaluation of learning

objects in the Hard Sciences also seems to include

potentiality indicators such as potential

and possible.

In addition to the frequencies indicated in Tables

4, we randomly examined the contexts in which

frequently used adjectives occurred within the

actual texts and found that each discipline group

tend to use descriptors in different semantic

contexts. For example, in Education the focus of

the descriptor “appropriate” are learners as it

describes such nouns as grade level, age,

or curriculum; in the Humanities reviewers

talk about appropriate material, sites, resources,

while in Hard Sciences they focus on the mechanics

or specific features of the learning objects (variables,

design features, labels, questions, for course,

locations, vocabulary, functions, level, gene

therapy).

Thus, the quantitative and qualitative analysis of

descriptors suggests that while academic

disciplines may utilize identical lexicon items,

they often do so at different rates and in

different contexts.

Table 4. Most Frequent Descriptors

|

Descriptor |

Education

N=218,731 |

Humanities

N=262,225 |

Hard Sciences

N=436,004 |

|

appropriate |

10 (213)* |

7 (175) |

7 (301) |

|

valuable |

6 (125)* |

3 (69)* |

1 (49) |

|

educational |

12 (269)* |

2 (64)* |

3 (110) |

|

instructional |

10 (225)* |

2 (62)* |

1 (38) |

|

professional |

9 (188)* |

1 (33) |

1 (41) |

|

social |

4 (91)* |

3 (77)* |

0 (12) |

|

specific |

13 (286)* |

6 (149)* |

8 (360) |

|

helpful |

9 (199)* |

6 (150) |

7 (285) |

|

new |

10 (218)* |

7 (196)* |

4 (181) |

|

national |

8 (184)* |

2 (45)* |

1 (38) |

|

best |

6 (133)* |

5 (120)* |

3 (114) |

|

scientific |

4 (84)* |

0 (8)* |

2 (99) |

|

multiple |

5 (106)* |

2 (65)* |

3 (143) |

|

authentic |

2 (37)* |

6 (148)* |

0 (3) |

|

native |

0 (6) |

5 (125)* |

0 (13) |

|

individual |

4 (87) |

6 (148)* |

4 (161) |

|

external |

1 (23) |

5 (141)* |

1 (47) |

|

primary |

4 (93)* |

8 (199)* |

2 (83) |

|

advanced |

3 (57)* |

11 (279)* |

5 (197) |

|

cultural |

2 (52)* |

10 (263)* |

0 (11) |

|

intermediate |

0 (10)* |

8 (210)* |

1 (34) |

|

historical |

2 (50)* |

7 (196)* |

1 (35) |

|

musical |

0 |

3 (83)* |

0 |

|

grammatical |

0 (3) |

3 (79)* |

0 (14) |

|

traditional |

1 (21) |

3 (79)* |

1 (56) |

|

independent |

3 (57)* |

6 (161)* |

2 (102) |

|

great |

4 (77) |

6 (156)* |

4 (177) |

|

clear |

7 (158)* |

14 (355)* |

11 (470) |

|

rich |

2 (40 )* |

3 (84)* |

1 (47) |

|

technical |

3 (60)* |

4 (98)* |

2 (103) |

|

mathematical |

2 (45) |

0 (1)* |

5 (215) |

|

physical |

2 (54)* |

0 (6)* |

3 (152) |

|

numerical |

0 (3)* |

0 (2)* |

3 (146) |

|

quantitative |

0 (4)* |

0 (2)* |

3 (125) |

|

graphical |

0 (6)* |

0 (2)* |

4 (168) |

|

potential |

3 (75)* |

2 (65)* |

6 (244) |

|

possible |

2 (52)* |

3 (82)* |

5 (199) |

|

limited |

3 (65)* |

2 (56)* |

5 (228) |

|

accurate |

2 (54)* |

3 (86)* |

6 (259) |

|

correct |

1 (24)* |

3 (75)* |

4 (188) |

|

interactive |

7 (161)* |

10 (254)* |

17 (738) |

|

effective |

6 (141)* |

5 (123)* |

8 (356) |

|

good |

11 (243)* |

11 (299)* |

16 (715) |

|

excellent |

9 (188)* |

10 (263)* |

14 (615) |

|

nice |

1 (26)* |

2 (62)* |

6 (275) |

|

different |

10 (216)* |

10 (275)* |

13 (588) |

|

similar |

2 (34)* |

2 (43)* |

3 (144) |

|

introductory |

2 (37)* |

2 (42)* |

9 (414) |

|

basic |

10 (213)* |

10 (261)* |

14 (592) |

|

simple |

5 (101)* |

6 (153)* |

13 (549) |

|

difficult |

4 (84)* |

4 (116)* |

7 (297) |

|

detailed |

2 (45)* |

3 (90)* |

4 (171) |

|

large |

3(64)* |

5(133)* |

9(377) |

|

little |

3 (56)* |

3 (85)* |

5 (210) |

|

small |

2 (50)* |

2 (52)* |

4 (155) |

Note:

Frequency per 10,000 words, raw number in

brackets.

Shaded are cells with words that are more frequent for a specific

discipline group.

*Significantly different proportions as compared

to Hard Sciences

(confidence interval >= 95%, p<=0.05, 2-tailed),

based on Z-test for two proportions

http://www.dimensionresearch.com/resources/calculators/ztest.html

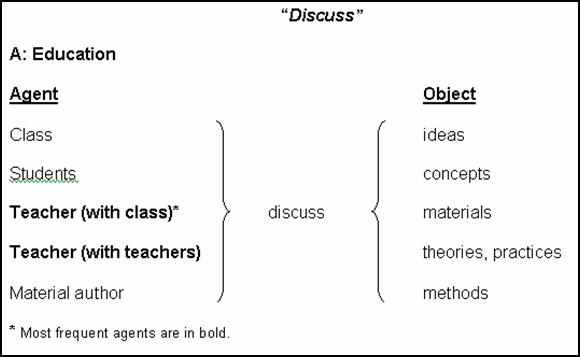

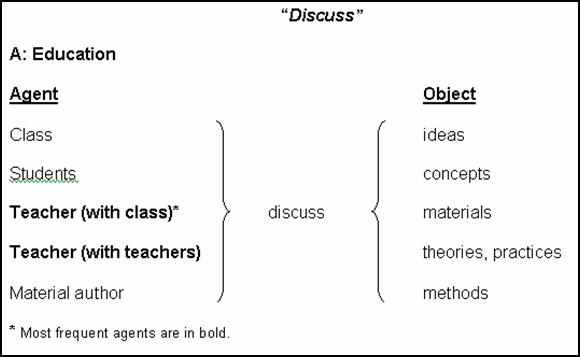

Processes and Agency

We use the Processes and Agency category to

document how the different disciplines use

language to describe processes and outcomes of

teaching and learning. This category focuses on

the action (e.g., teaching, learning, interacting,

etc.) and the agent of the action, the one

who performs the action. The English language can

express the agent of an action explicitly (SHE

learned her lesson) or implicitly through use of

the passive construction (The lesson was learned

(by HER) or by implication (materials for

discussion (by STUDENTS)). By examining the

contexts in which the most frequently used lemmas

that denote teaching and learning actions

appeared, we attempt to establish whether

differences exist in who is seen as performing the

teaching and the learning with the learning

objects being reviewed and, by extension, each

discipline’s priorities for agency in the

instructional processes.

Indeed, through examining the contexts of

use for the most frequently used actions across

the three disciplines, we see distinct differences

in terms of how and by whom instructional

processes are undertaken. A typical illustration

of this concerns the use of discuss:

Typical context:

The resulting printouts are rich and can be

used in a variety of ways to discuss teacher

dispositions, the classroom teaching environment,

the school work environment, etc.

As illustrated above, the lemma discuss most

frequently carries teacher as agent. Discuss was

also frequently used in the context of discussion

boards (used by teachers), ways to facilitate

class discussions, and the roles for discussion in

teaching and learning methods. In the vast

majority of cases, the action of discussing

carried teachers as the agents of the action. As

most learning objects in the Education discipline

of MERLOT are geared toward teacher education and

teacher support materials, the teacher as agent

makes sense as the most common form of agency,

especially in light of the fact that contemporary

Education generally sees the agency of teaching

and learning primarily with the professional

educators who undertake instructional practices.

The vast majority of actions are in the context of

teacher learning, professional dialog and

professional development.

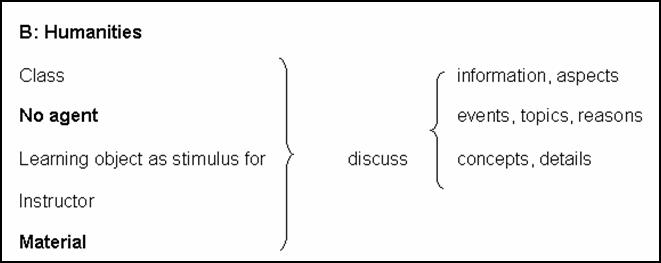

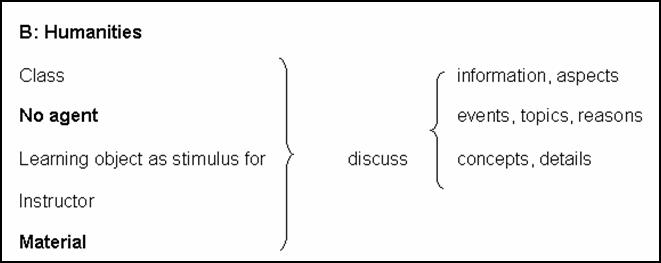

As compared to Education, we can see that the main

source of agency in the Humanities learning object

reviews tends to be null; that is, the passive

form with no apparent doer of the action.

Typical contexts:

The elemental level is discussed very

briefly. (Music)

The exception to this trend is in the World

Languages reviews where students/learners are the

most frequent agents of the action discuss:

Students can write to each other and discuss

topics that interest them such as experiences with

learning English… (World Languages)

In the case of this action, discuss/discussion,

there is a clear difference between the

disciplines within the Humanities. Unlike Music

and History where the agent is typically null or

the materials themselves, in World Languages, a

discipline for which emphasis on active student

communication is key, students are most often the

agents. Where there were no instances of student

agency attendant to the lemma discuss and its

derivative in the History and Music reviews, in

World Languages there are 83 instances out of 167

where students are written of as the agents, the

actors of discuss: e.g., class/student discussion,

discussion questions, discussion groups,

springboard/catalyst/stimulus for discussion.

Finally, in the other two Humanities categories,

Music and History, the construct whereby agency is

given to the learning object itself (“allows for

discussion”) occurs frequently throughout.

C: Hard Sciences

Where there are 363 instances of some form of the

lemma discuss in the Hard Sciences data,

there is not one instance of the active tense with

student nor instructor acting as agent of the

action. Every instance is either passive “is

discussed” whereby agency is absent entirely, or

with inanimate subjects such as sites (“the site

discusses”), texts (“the text discusses”), page

(“the page discusses”), the researcher (“the

researcher discusses”). The exception is thirteen

instances of the phrase “for class discussion” and

four instances of “discussion point” both implying

agency on the part of instructors and students;

participation in the former, accessing in the

latter.

There are, therefore, differences, some salient,

some subtle between the three disciplinary

categories in terms of how teaching and learning

gets done; specifically between the sources of

agency and the guiding of instructional processes.

In writing their reviews of digital learning

objects, Education faculty see the agency of

teaching as lying with teachers, less with

materials and less with what learners see and

interact with on the computer screen. Contrary to

this trend, Humanities faculty imbue materials

with the agency of teaching and learning with the

Hard Sciences attributing the acts of teaching and

learning to the computer application per se. It is

clearly the case that there are distinct ways of

perceiving and expressing the activities of

teaching in learning as reflected in this corpus.

Syntactic

Features

The syntax used in the different disciplinary

discourses could be equally as suggestive as the

choices of vocabulary. Moreover, examination of

the reviews’ syntactic features can distinguish

features among registers including those that are

characteristic of the particular academic

discipline. The length of the text, relative

organization of the sentences inside the text, as

well as the sentence internal structure that

reveals the relationship between parts of speech,

characterize the discourse explicating its

individual features. Biber and his co-authors, for

example, show that corpus-based linguistic

analysis of syntax may contribute to

characterizing texts on such dimensions as

involved versus informational production,

narrative versus non-narrative

discourse, or impersonal versus

non-impersonal styles (Biber, Conrad, & Reppen,

2002, pp. 135-171).

For the purposes

of our study, we examined three syntactic features

of the texts: 1) text and sentence length; 2)

passive constructions; and 3) bulleted

constructions. In each of the three discipline

groups a number of texts were randomly selected.

30 texts each were extracted from the Education

and Humanities groups with 45 texts comprising the

randomly selected texts in the Hard Sciences.

Figure 2

summarizes the results obtained after the selected

reviews undergone concordancing, hand coding and

descriptive statistical analysis.

Figure 2. Syntactic

Features by Discipline

Text and

sentence length

The calculations

reveal that reviews in Education are on average

lengthier: here an average review comprises of 44

sentences as compared to 33 and 34 sentences in

the Humanities and the Hard Sciences respectively.

At the same time, the sentence length in all three

disciplines is similar: the average sentence in

Education is comprised of 19 words, in Humanities

– 18 words, in the Hard Sciences – 17 words.

The results suggest that while reviewers

in Education are wordier and choose to provide

lengthier evaluations of their digital learning

objects, they tend to express their thoughts in

sentences that are as long as sentences selected

by their colleagues in the Humanities and the Hard

Sciences. It seems that educators, being very well

versed in assessing teaching tools, are more

verbose when reviewing MERLOT learning objects,

activity that requires the assessment of the

learning object’s potential effectiveness as a

teaching/learning tool.

Passive

constructions

It is

generally accepted that passive forms are more

often used in formal documents and are frequently

featured in science texts. Passive constructions

make a text sound more impersonal (Biber, Conrad,

& Reppen, 2002), that is, more objective. While

taking in to account that the academic nature of

reviews under analysis implied a certain degree of

formality, we hypothesized that this degree could

vary between the different discipline groups. The

results, however, contradicted our predictions as

seen in Figure 2. With 167 instances of passive

forms per 10,000 words in Education, 157 instances

in the Humanities, and164 instances in the Hard

Sciences, we can not claim that any discipline

group tends to use passive constructions

considerably more frequently

The findings suggest that reviewers in

different discipline groups use passivization at a

similar rate. Apparently, shared understanding of

the target audience and purpose of the texts they

produce, make reviewers of digital learning

objects select similar syntactic constructions.

Bulleted

constructions

While collecting

data to describe syntactic peculiarities, we

noticed that many reviews in the Hard Sciences

contain bulleted constructions. Reviewers in this

discipline group often prefer to describe learning

objects not in paragraphs of connected sentences

but rather in bulleted shorthand. Thus, some of

these constructions do not represent fully

developed sentences with subjects and predicates.

Additionally, reviewers tend to mix complete

sentences and those where some important parts of

speech are omitted but easily derived from the

sentence stem. Even when writing in full

sentences, reviewers may omit a part of the

predicate – usually the linking verb “to be”. For

example, when describing the quality of content,

one of the reviewers writes the following:

Quality of Content: (4.60)(4.00) = 4.3

·

Layout fairly

well designed

·

Material complete

allowing many factors to be tested in a single

simulation

·

Accurate with

excellent references to justify simulations

Such bulleted constructions allow for quick and

concise verbalization of the observation. They

save time over developing text cohesion and

worrying about such relatively insignificant

elements as linking verbs or punctuation marks for

sentence meaning. The fact that bulleted

constructions are much more frequent in reviews in

the Hard Sciences could be explained by the

non-narrative (factual, informational) concerns of

texts in ‘pure’ science (Biber, Conrad, & Reppen,

2002).

Bullets also

allow for visual separation of thoughts, so

important in the information era where visuals

assume a leading role in providing information.

Wide usage of bulleted constructions could also be

explained by gradual penetration into academic

writing of language features we tend to associate

with electronic communication – e-mailing, instant

messaging, presenting information in PowerPoint

format. It would probably be safe to say that the

acceptance of bulleting means that the electronic

“version” of academic writing has become more

democratic, less formal and more graphical (Tufte,

2003).

Implications

Like Motta-Roth’s study of book reviews from three

disciplines, a study which revealed distinct

differences between discipline-specific

methodological approaches, this study finds that

variation in faculty use of language in composing

digital learning object reviews is distinct. In

the Motta-Roth case, implications were drawn for

the teaching of English to non-native speakers. We

too see the need for both native and non-native

speakers to be made aware of the differing uses of

the language of teaching and learning between

disciplines as part of advanced academic

preparation; e.g., the professoriate in training,

policy/administrative staff.

Additionally, the growing field of instructional

technology design and support for technology-using

faculty would also benefit from understanding and

perhaps making use of these differences

productively in their work with faculty from

varying disciplines. Finally, the complex

conceptual frames and accompanying discourses used

by each discipline can potentially enrich one

another through productive, collaborative and

synergistic work around instruction in general and

the evaluation of digital learning objects in

particular.

Conclusion

As the world of information grows more dense and

complex, so too do academic disciplines. As a

result, disciplinary language becomes increasingly

compartmentalized with a loss of mutual

intelligibility between and across disciplines

becoming more than a remote possibility. Such

divisions have often been cited as limiting

intellectual growth and discovery due to lack of

communication between groups. “Disciplinary

specialization inhibits faculty from broadening

their intellectual horizons—considering questions

of importance outside their discipline, learning

other methods for answering these questions and

pondering the possible significance of other

disciplines’ findings for their own work” (Stober,

2006, p.317). With faculty from diverse

disciplines now finding themselves in mixed venues

for the purpose of developing instructional

technologies, opportunities for broadening their

instructional horizons through

cross-disciplinary conversations abound.

We share the view that learning about or forming

connections between fields of knowledge is an

essential educational need for success in the 21st

century (Caine & Caine, 1991; Dwyer, 1995; Jacobs,

1989; Martinello & Cook, 1994). Using digital

learning objects as catalysts for productive

discussion of instructional practices represents a

promising beginning. Where Bradbeer (1999)

encourages the dissolution of disciplinary

discourse barriers through movement toward

commonality, we suggest quite the opposite: an

awareness building and promotion of mutual respect

for one another’s epistemologies and practices as

expressed in what is ostensibly a common language

of teaching and learning.