|

|

| MERLOT Journal of Online

Learning and Teaching |

Vol.

5, No. 4 December 2009

|

Online Teaching Experience: A Qualitative Metasynthesis (QMS)

|

Jennie C. De Gagne

Assistant Professor

North Carolina Central University

Durham, NC 27707 USA

jdegagne@nccu.edu

Kelley Walters

Associate Professor

Northcentral University

Prescott Valley, AZ 86314 USA

kwalters@ncu.edu

|

Abstract

Qualitative studies of educators who teach online are crucial to provide direction for practice and research as they offer an emic perspective. Using a qualitative metasynthesis (QMS) design, this study investigated the experience of online educators at institutions of higher education in the U. S. Discerning what activities online educators could instigate to bridge the gaps between the best practices and the present instructional realities in online teaching, this study provides an interpretive synthesis of the meaning of teaching online as represented by a body of qualitative literature on online education. The chosen theoretical framework for the study includes the model of critical thinking and community inquiry. The researcher identified nine original qualitative studies involving 203 participants in geographically diverse schools. Close reading of the nine studies identified four key themes that captured the nature and experience of online instructors: (a) work intensity, (b) role changes, (c) teaching strategies, and (d) professional development. Many of these themes were linked to each other and, therefore, contributed to a broader picture of the instructors’ experience. The results of the study substantiate previous research and can benefit all stakeholders including learners, faculty members, and leaders in colleges and universities that offer online education.

Keywords: Online teaching, qualitative study, qualitative metasynthesis, higher education, distance education

|

Introduction

E-learning, which is course content delivered electronically, has gained popularity with adult learners because it reaches people for whom traditional systems are inaccessible due to long geographical distances from traditional classrooms, or busy lives with families, a profession, or other responsibilities. The growing prominence of e-learning among academic institutions, industry, training establishments, governments, and international organizations is attributed to associated benefits. For instance, academic institutions cited cost effectiveness, resource maximization, increased enrollment, revenue enhancement, and competitive edge as reasons for promoting e-learning (Schiffman, Vignare, & Geith, 2007). Based on the growth in online enrollments (Allen & Seaman, 2007), there is a need for online training and professional development for educators; however, the specifics of such training have yet to be assessed. Using a qualitative metasynthesis (QMS) design, the purpose of this study was to examine the perceptions of educators about online teaching, specifically how faculty have altered their standard andragogy to meet the needs of e-learning students.

Background of the Study

The use of new technologies has allowed people greater potential to reach their goal of achieving an excellent education anytime and anywhere. Among the technologies available for instructional purposes, e-learning is the most significant phenomenon in contemporary education (Lowenstein & Bradshaw, 2004). As Uhlig (2002) reported, little research has focused on how e-learning has impacted faculty teaching methods, such as their ability to effectively reach out to learners with various teaching or learning styles. The transition from overhead projector and chalkboard to a virtual environment necessitates new ways of thinking and teaching, and faculty must adjust their pedagogy to effectively and efficiently facilitate learning at a distance.

Although the future of online enrollment growth is assured, faculty acceptance of online education is consistently cited as a significant barrier issue for academic leaders (Allen & Seaman, 2007). While educators are committed to putting effort and energy into technology-embedded learning environments, current technology evolves at a fast pace, leaving them, at times, overwhelmed and confused (Kim & Bonk, 2006). Additionally, they face the challenge of maintaining pedagogical integrity to keep a balance between individual needs and group interaction ( Bull, Knezek, Roblyer, Schrum, & Thompson, 2005). To overcome these obstacles, educators must be provided with continuous support that includes the necessary technology, professional development programs, and technical assistance.

Purpose and Research Question

The purpose of this qualitative study was to investigate the experience of online educators at institutions of higher education in the U. S. and to provide an interpretive synthesis of the meaning of teaching online. A preliminary review of the literature revealed that several studies have been conducted on the topic of the experience of educators with online teaching. However, the review of existing studies did not reveal any attempt for a synthesis approach that would provide a deeper level of understanding. Hence, the research question, “What have researchers discovered about the experience of teaching online in higher education?” guided the research design.

Theoretical Framework

As Anderson, Rourke, Garrison, and Archer (2001) posited, online teaching is an extremely complex and challenging undertaking; therefore, studies of online educators’ multifaceted functions must adopt a solid framework that can lead to a better understanding of their roles. The theory of critical thinking and community inquiry (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000) is especially useful for understanding the online teaching experience. Specifically, teaching experience illuminates the preparations online educators should make to enact their roles in the online environment. Providing a conceptual means for the study of online educators’ experience, this model consists of three elements essential for educational experience, which are (a) cognitive presence, (b) social presence, and (c) teaching presence (Garrison et al., 2000).

Cognitive Presence

Cognitive presence is the level and depth of critical thinking that is evidenced in interaction and communication among members in a learning community (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005). Manifested through the community inquiry process, cognitive presence can provide a means to access the systematic progression of knowledge acquisition (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2001). Picciano (2002) made a distinction between interaction and presence given that the quantity of interaction does not reflect the quality of cognitive presence. Rejecting interaction as unequal to cognitive presence, Garrison and Cleveland-Innes synthesized some of the literature and concluded that the interaction, or critical discourse, must be structured and cohesive for students to reach high levels of critical thinking and knowledge construction. They also claimed that online learners do not always display cognitive presence, suggesting that social and cognitive adjustments need to be made to produce positive learning outcomes. Hence, whether online or face-to-face, levels of thinking and knowledge construction are learning goals, and the higher-order learning process emerges in the system of critical thinking and community inquiry (Cleveland-Innes).

Social Presence

Social presence has been defined in various ways, but the one most often cited comes from the seminal work of Short, Williams, and Christie (1976) in social presence theory. Short et al. (1976) defined social presence as the “degree of salience of the other person in the interaction and the consequent salience of the interpersonal relationship” (p. 65). Social presence is the ability of participants within the online learning community to project their personal characteristics into the community and present themselves as real people (Garrison et al., 2001).

Social presence creates the community and sense of connectivity that is somewhat lacking in online classes (Tu & McIsaac, 2002). Recent literature has shown that social presence is one of the most significant factors in improving instructional effectiveness and building a sense of community (Aragon, 2003). This connection and feeling of being part of a learning community is important not only for satisfaction but also for effective learning outcomes. A strong sense of community reduces feelings of isolation and minimizes student burnout while promoting interaction and cooperation among peers ( Rovai, Ponton, Wighting, & Baker, 2007 ). Creating an environment to increase social presence in online learning is a way to enhance interactions between students and the instructor, dispel feelings of aloneness, and significantly increase cognitive learning (Aragon).

Facilitating the sense of community and belonging, creating a safe environment for communication, as well as building and sustaining a sense of group commitment to learning, also aim at creating social presence (Garrison et al., 2001). As Swan and Shih (2005) reported, increased social presence is directly correlated to higher student satisfaction. Through other findings, Swan and Shih demonstrated that the perceived presence of instructors may be a more influential factor in determining student satisfaction than is the perceived presence of peers. The primary role of social presence is to function as a support for cognitive presence. However, when members perceive the experience as enjoyable, satisfying, as well as personally and professionally fulfilling, they tend to interact more and remain in the cohort of learners for the duration of the program (Mykota & Duncan, 2007). Social presence therefore contributes to the overall success of the educational experience. The result of this growing field of inquiry demonstrates that the understanding of social presence theory is essential for current and prospective online educators to further the development of social presence in their teaching practice.

Teaching Presence

Teaching presence is defined as the “design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcome” (Anderson et al., 2001, p. 5). Pertinent to the design and development of the educational experience, teaching presence is primarily the responsibility of the instructor (Anderson et al.). As such, the teaching presence facilitates the overall interaction of the learning community. According to Anderson et al., the teaching presence consists of three characteristics: (a) design and administration, (b) discourse facilitation, and (c) direct instruction. The process of designing and planning online courses is usually more time-consuming because instructors must create a more explicit and transparent course in an electronic format, which requires more deliberation in designing the process, structure, and evaluation, along with the interaction components of the course (Anderson et al.). In the process of design and administration, instructors must plan some time for group activities and student project work, a very important aspect of online courses (Ko & Rossen, 2004).

Given that an increasing number of faculty members at institutions of higher education are asked to teach online, it is important to consider their perspectives on teaching adults in this environment. The theory of critical thinking and community inquiry was selected because of its direct applicability to the experience of online educators. This theoretical model is more than a social community and more than the magnitude of interaction among participants (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005). Furthermore, this framework is the integration of cognitive, social, and teaching presences, all of which address the qualitative nature of participatory inquiry consistent with the ideals of higher education (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes). In this study, the theory of critical thinking and community inquiry provided a framework for developing research questions regarding educators’ experiences in an online environment.

Methods

This study adopted a Qualitative Metasynthesis Study (QMS) design, generating new interpretive findings from existing qualitative studies related to online teaching in higher education. By analyzing published articles in peer-reviewed journals and doctoral dissertations, a comprehensive chronicle of the phenomena of online educators’ teaching experience was explored. The following were set for the inclusion criteria for the studies: (a) Qualitative studies that explored the meaning or experience of teaching online in a higher education institution, (b) studies that used qualitative data analysis methods such as content analysis, narrative analysis, or an unspecified qualitative analysis, (c) studies published in English that contain qualitative data, and (d) articles published in peer-reviewed journals and doctoral dissertations between 2003 and 2008.

Sample Strategies

Searching multiple databases is a must for retrieving all relevant qualitative studies and is the most commonly used technique (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007). Nevertheless, appropriate manipulations of search terms require searchers’ knowledge about the basic mapping patterns of a database (Sandelowski & Barroso). As Patton (2001) noted, purposeful sampling is the dominant strategy in qualitative research, which seeks information-rich cases that can be studied in depth. In retrieving samples relevant to the topical parameter, purposeful sampling was conducted using electronic bibliographic databases such as ProQuest, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), PsycINFO, and Academic Search Premier.

To minimize bias against non-published research literature, a search through Dissertation Abstracts International and ProQuest Dissertation and Theses was also conducted. Limiting searches to English-language literature excluded studies conducted in the U.S. but reported in non-English language environments. Because this study was targeting online educators who teach in the U.S., one dissertation that investigated Argentina faculty’s perception of their teaching was excluded.

Initially, the search terms online teaching and asynchronous teaching as well as their variations and combinations were used to identify potential studies for use in this study. Wildcard versions as well as multiple versions of these terms, for example, e-teaching, distance teaching, teaching online, or Web-based instruction, were also used. Author searching, citation searching (i.e., descendancy approach), and footnote chasing (i.e., ancestry approach) were utilized. Finally, a hand search of relevant journals (e.g., Innovative Higher Education, Journals of Technology and Teacher Education) was conducted to identify articles that may have been overlooked in the previous procedures. This rather large initial pool was then narrowed to studies based on (a) scholarly research, (b) qualitative studies, (c) English-written studies, and (d) studies about experiences of educators who teach online. The final data set consists of 9 reports that contain 4 published and 5 unpublished reports .

Data Analysis

Noblit and Hare’s (1988) meta-ethnographic methodology is appropriate for QMS studies in that the methodology of meta-studies has many similarities with meta-ethnography because both are integrative approaches in the phenomenological tradition (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007). This inductive and integrative approach draws a systematic comparison through seven phases as listed below.

Step 1. Getting started and deciding on a phenomenon of study : This first step is to identify an area of interest worthy of synthesis. The experiences of teaching online were chosen as the area of interest in this study.

Step 2. Deciding what qualitative studies and interview data are relevant to the initial interest : This phase involves conducting a literature search for studies and interviews to include in the analysis. Relevant studies were reviewed to narrow down the selection based on the inclusion criteria stated earlier.

Step 3. Reading the qualitative data : This step allows for the extraction of interpretive metaphors. All data must be read and re-read to identify key metaphors, themes, or concepts. Detailed notes were kept on these themes, concepts, and metaphors.

Step 4. Determining how the data are related to each other : Lists of key phrases, themes, concepts, or metaphors from the data are listed and juxtaposed. Preliminary assumptions were made in regard to the relationships between data.

Step 5. Translating the data into one another : Translations are written based on the tentative assumption derived from the previous phase. Metaphors of the individual findings and their relationship remain intact but allow the comparison of results from one finding to those in the other data.

Step 6. Synthesizing the translations : This step is a second level of synthesis used when a large number of data is involved, allowing for a higher level of abstraction. At that point, the study was reviewed and the translations were synthesized, which involved “putting together” a whole that revealed more than the sum of all individual data.

Step 7. Expressing the synthesis in written words : In this final phase, the synthesis is expressed in a form that communicates effectively with the target audience (Noblit & Hare, 1988, pp. 26-29).

Findings

The goal of this study was to investigate the experience of online educators at institutions of higher education in the U.S. In conducting the QMS, the first step was to construct a table of metaphors for each of the studies. Using the search procedures and inclusion criteria previously described, nine original reports of qualitative study about the experience of online educators were identified. Demographics and methodological characteristics of all the studies included in this QMS are provided in Tables 1 and 2. Table I shows that these reports involved 203 participants working in geographically diverse schools. As seen in Table 2, various qualitative designs were used in these studies, and the most frequently used qualitative design was a descriptive design that included phenomenology and an exploratory descriptive study (n = 6), followed by a case study (n = 2) and one grounded theory (n = 1). The disciplines or fields represented by the selected studies were Education (n = 4), Curriculum and Instruction (n = 2), Psychology (n = 1), Information Systems and Technology (n = 1), and Nursing (n = 1).

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

Title of Study |

Author/Year |

Publication/Data Source |

Number of Individuals in Study |

Individual Variables

(e.g., age, nationality, and gender) |

Faculty lived experience in the online environment |

Conceição/2006 |

Adult Education Quarterly |

10 |

- 5 females, 5 males

- Teaching different disciplines in various academic institutions

|

Online teaching as experienced by teachers |

Gudea/2005 |

Unpublished doctoral dissertation |

44

|

- Representing 32 educational institutions

- 66% males, 34% females

- Representing a wide range of teaching modalities and various subject areas and specializations

|

Understanding online learning through a qualitative description of professors’ and students’ experiences |

Lao & Gonzales/ 2005

|

Journal of Technology and Teacher Education |

6 |

- No gender or nationality identified

- Teaching the same discipline in the same school

|

The preparation of faculty to teach online |

Lewis/2007 |

Unpublished doctoral dissertation |

6

|

- No gender or nationality identified

- Representing different subject matters

|

Implementing effective online teaching practices |

Lewis & Abdul-Hamid / 2006 |

Innovative Higher Education |

30 |

- 17 undergraduate and 13 graduate instructors

- Teaching various subject areas and specialization but from the same institution

|

Disembodiment for the sake of convenience |

Meyer/2004 |

Unpublished doctoral dissertation |

3 |

- 2 males, 1 female

- Representing the same educational institution but teaching different subject matters

|

Teaching at a distance |

Oliver/2004 |

Unpublished doctoral dissertation |

17 |

- 35% males, 65% females

- More than 70% are over 46 years old

- More than 80% have over 11 years of teaching experience at college level

- All interviewees received training for the design and the development of online courses

|

Roles of faculty in distance learning and changing pedagogies |

Ryan, Carton, & Ali /2004 |

Nursing Education Perspectives |

19 |

- Participants drawn from 8 nursing schools

- No gender or nationality identified

|

Voices of faculty and student |

Turner/2005 |

Unpublished doctoral dissertation |

68

|

- n = 57 (faculty face-to-face focus group participants)

- n = 11 (faculty asynchronous focus group participants)

- Representing various subject areas and specializations

|

Table 2. Methodological Characteristics of Included Studies

Study |

Discipline Published in |

Geographical Location of Study |

Qualitative Research Design |

Data Collection Method |

Data Analysis Method |

Conceição (2006) |

Education |

USA, Canada |

Phenomenological study |

Semi-structured interviews |

Qualitative descriptive |

Gudea (2005) |

Information Systems and Technology |

USA |

Grounded theory |

Interviews |

Constant comparative |

Lao & Gonzales

(2005) |

Education

|

USA |

General descriptive design |

Structured interviews |

Qualitative descriptive |

Lewis &

Abdul-Hamid (2006) |

Education

|

USA |

General descriptive design |

Interviews; focus group discussion |

Constant comparative |

Meyer (2004) |

Education

|

USA |

Case study |

Interviews; focus group discussion |

Thematic analysis |

Oliver (2004) |

Psychology |

USA |

Case study |

Surveys and interviews |

Qualitative descriptive |

Ryan, Carton, &

Ali (2004) |

Nursing

|

USA, Canada |

Exploratory descriptive study |

Interviews; focus group discussion |

Constant comparative |

Turner (2005) |

Curriculum and Instruction |

USA |

Exploratory descriptive study |

Focus group discussion |

Constant comparative |

Emerging Themes

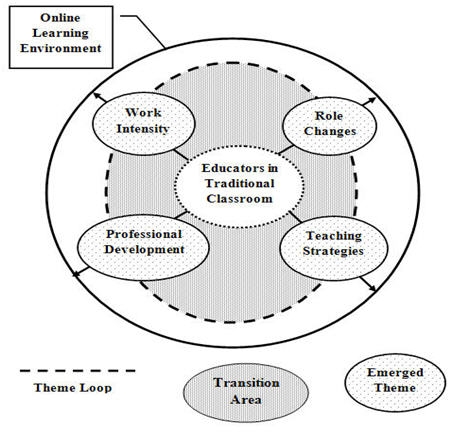

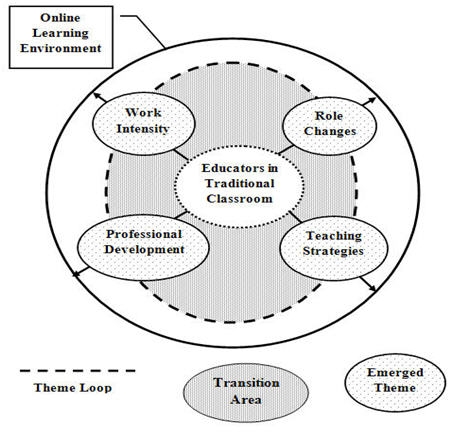

Close reading of the nine studies identified four key themes that captured the nature and experience of online instructors: (a) work intensity, (b) role changes, (c) teaching strategies, and (d) professional development. Many of these themes were linked to each other and, therefore, contributed to a broader picture of the instructors’ experience. Below is a descriptive and interpretive report of the lived experiences of online educators under each of the four overarching themes.

Theme 1: Work intensity . All of the included studies documented work intensity. More preparation was needed when teaching online and successful instructors greatly relied on preparedness and organization skills. Online educators felt that online teaching was challenging because they spent more time on planning, designing, delivering, and evaluating online instruction. The perception of workload may have been affected by the “non-stop” nature of online teaching, “constant” feedback and clarification, and higher expectations from learners. In many cases, online educators had to rearrange their daily routines so that they could become more accessible to their students who expected instantaneous responses. Class sizes also affected online instructors’ workload because, when they had more students, they needed more time to check their students’ assignments and more time to post discussions. Not only was class size a big concern, but so was the type of teaching level (i.e., undergraduate or graduate) and the number of classes allotted in a particular semester.

Across all the investigations, online faculty members expressed concerns about the increased workload, which might have been lessened had there been an integration of a face-to-face component ( Conceição ; 2006; Lewis, 2007; Turner, 2005). As Thompson (2004) argued, there is little empirical literature showing that online teaching is less time-intensive than face-to-face teaching. This assertion has been supported by an emerging theme, work intensity. The consistency of this metaphor provides evidence for conformity of thought across the studies.

Theme 2: Role changes. Using various approaches, all nine studies were conducted in different times and places, and yet there was unanimity among those studies about role changes. Online educators felt they were like a coach, facilitator, conductor, director, mentor, or co-learner. One of the most significant transformations was from lecturer to guide, from knowledge dispenser to resource provider, and from authority to facilitator. As a facilitator, online educators were trying to encourage their learners to introduce themselves, exchange with their peers, and share their background and professional experiences. In doing so, they were able to initiate an engaging and welcoming virtual learning environment. In some cases, online educators felt their relationship with students became stronger, more comfortable, and even enduring (Ryan et al., 2004).

As illustrated in the section of theoretical framework, this study adopted the model of critical thinking and community inquiry (Garrison et al., 2000). Among the three concepts in this model, teaching presence is closely related to the second theme, role changes, as it is geared to attain personally and educationally worthwhile learning results. Indeed, teaching presence is primarily the responsibility of the instructor, creating explicit and transparent courses and discoursing facilitation (Anderson et al., 2001). Participants in the studies redefined their roles, echoing that their roles had been transformed in a way that they empowered their students via promoting critical thinking and active learning in the classroom.

Theme 3: Teaching strategies . A number of participants in the studies involving teaching online expressed the urgency of strategizing their teaching skills. The main domains where faculty wanted to develop and improve in the online learning environment were the access and familiarity with technology, while promoting reflection skills and collaboration among students. Some instructors were concerned about the difficulty in using some of the technology available to them, finding it to be excessively complicated from time to time.

Support for Lao and Gonzales’ (2005) construct is echoed in the majority of studies in this synthesis. For example, Lewis (2007) observed that technically less prepared faculty heavily relied on course developers and designers to build their courses, while technically more prepared faculty focused more on the actual teaching of their courses than on the technical aspects. A participant in Meyer’s (2004) study expressed that keeping up with technical changes is like “chasing the wind” (p. 142). There was also an indication that faculty’s receptivity to online teaching was closely related to their background and proficiency in using technology in class (Lao & Gonzales).

Some instructors in the studies reported that learning more about their students beforehand was very helpful in that they could better address their strengths and weaknesses. In creating this type of mutual learning community, participants in the studies claimed the utilization of discussions as one of the most effective teaching strategies. In many respects, online instructors liked to use case studies because they perceived that such real-life examples could draw student interest and motivation, which ultimately promotes active learning (Gudea, 2005; Ryan et al., 2004; Turner, 2005). Facets of the needs or importance of developing online teaching skills were revealed in all the included studies. The basis of the third metaphor or theme, teaching strategies, is underpinned by the belief that collaborative learning processes would allow students to achieve deeper levels of knowledge generation. It has been synthesized from the included studies that the creation of shared exploration of meaning-making and the reflective learning process is the foundation of teaching effectively online.

Theme 4: Professional development. Although there was consensus that online teaching is time and work intensive, online teaching was perceived as stimulating and satisfying for many of the study participants because of the opportunity offered for professional growth. Comments from Ryan et al.’s (2004) study were: “As a teacher, I feel exhilarated;” “There is a lot of synergy in the group, and especially a commitment to work together;” “I’m excited about the new possibilities;” “I like to be doing cutting-edge stuff” (p. 78). Nonetheless, just as not all students should consider taking online courses, not all faculty members were keen on teaching online.

Meyer (2004) extensively discussed in her study that the lack of physical presence was a source of dissatisfaction for many online educators. She defined this isolation in cyberspace as disembodiment because online educators felt detached from their peers and from students, which led to a sense of unreality and disassociation. Nonetheless, those who hold negative feelings about teaching online admit that the move to online technological applications as a trend is inevitable. Therefore, both positive and negative aspects of teaching online must be acknowledged and greater attention should be paid to how administrative support can boost online instructors’ professional development. Findings in the included studies revealed that instructors wanted to have more administrative assistance in terms of curriculum advising and guidelines, as well as more peer collaboration to share best practices. Given that most institutions of higher education will deliver at least a portion of their course offerings online, there will still be room for both those who choose to teach in a traditional classroom and online.

The last emerged theme, professional development, indicates that online educators need ongoing faculty development and training. That is, online educators must be provided with continuous support that includes the necessary technology and professional programs, which has been echoed by participants in the included studies. As researchers concluded in their studies (Gudea, 2005; Meyer, 2004), training and faculty development should not focus on the technology itself but on increasing interactivity in online classes, delivering course content in an innovative way, and on empowering learners. To prepare faculty to teach successfully online, administrators must be able to articulate how their support relates to professional growth of online educators who teach online. The following diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the four themes emerging from the meta-synthesis of qualitative studies about online educators’ teaching experiences.

Limitations of the Research Findings

The present study contains certain limitations of the research findings that need to be taken into account when considering the study and its contributions. First, the representativeness of the study sample cannot be determined through the population of 203 participants in the QMS. Even though QMS studies provide a mechanism with which to go beyond interpretation through the integration of multiple studies, they are nonetheless limited to the findings of studies included in the research. In addition, the results of qualitative studies about online educator’s experiences may have shown that differences existed not only among studies (e.g., theoretical framework, methodology, and analysis) but also among the events in participant’s real experiences, as well as in their narratives of those events. Therefore, it was imperative to construct a plan to create reliable empirical integrations of qualitative research findings.

Figure 1. Four overarching themes from QMS study. This drawing illustrates how online educators perceived online teaching through their personal experience synthesized in the nine included studies. Although faculty had their unique experience while teaching online, they all made some transition from teaching traditional classroom to online environment.

Conclusions and Recommendations

As today’s learners are seeking more economical and convenient ways of earning a degree in higher education, online educators must understand their needs, as well as the implications of using technology in education. While providing well-developed and cost-effective learning materials to e-learners is essential, educators must develop new technology skills for course design, delivery, and evaluation in online environments (Schiffman et al., 2007). The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of educators who teach online at an institution of higher education in the U.S. By integrating a synthesis of literature, the study aimed at providing a comprehensive chronicle of the phenomena of online teachers’ perceptions. Conducting the qualitative metasynthesis (QMS) study, this researcher identified nine original qualitative studies about the experience of online educators. These reports involved 203 participants working in geographically diverse schools of higher education in the U.S. Different designs of qualitative studies were used in these archives, and the disciplines taught by the participants also varied. The following section is to discuss the implications of findings, limitations of the study findings, and recommendations for future research.

Discussion and Implications of Findings

It is concluded from the present study that the concepts of learner-centeredness and social presence are important to faculty teaching online. While teacher-centered education allows educators to make all decisions without learners’ input, learner-centered education facilitates students’ participation in making decisions about their own learning (Allen, 2005; Savery, 2005). In line with the learner-centered approach, social presence was identified in this study as the essence of building trust and promoting a sense of community. Consistently illuminated across the findings of the study, the identification of a social presence concept implies that online teachers must be visible so that students are able to ‘see’ and ‘hear’ their instructors. It is easy to assume that if students felt their instructors were non-participative, they would perceive them as not interested in teaching, which could lead students to take a passive role (Savery). Therefore, online teachers must be aware of the notions of learner-centeredness and social presence, both of which promote learners’ active learning, fully integrating these best practices into their existing teaching styles. The implication of this finding for practice is that a solid learner-centered environment and instructor visibility will lead to greater participation, teamwork, respect, and commitment from teachers and students.

Results also indicate that there is unanimity among online instructors about role changes, which was articulated as references of coach, facilitator, conductor, director, or mentor. Such role changes perceived by online educators are well documented in numerous literature resources and were also addressed in this study. This finding implies that the recognition of transition from lecturer to guide, knowledge dispenser to resource provider, and authority figure to facilitator (Ko & Rossen, 2004; Ryan et al., 2004), is significant for online teaching because a lack of clarity about roles and expectations is likely to precede failure. By a cknowledging a reallocation of power in the classroom, online educators instill a learner-centered learning environment in which students become empowered to take charge of their own learning and achieve greater learning outcomes.

Finally, the results of this study suggest that online teachers believe in a wide range of leadership roles that help build and maintain high-quality online teaching. Although there is a limit to what leadership can do to help teachers improve their pedagogy, supportive measures sought by online teachers are: (a) administrative support, such as offering professional development programs, (b) detailed training including technical support, and (c) performance-based incentives. Researchers underscore that educators must master new sets of skills and knowledge when teaching online. In addition to their existing repertoire of teaching skills, educators must understand the nature of online education, the characteristics of online learners, the design of Web courses, and diverse online teaching strategies (Tu, Yen, Corry, & Ianacone, 2003). Contrary to the assumption that teachers should know how to teach online since they are actually doing it, the findings of this study suggest that faculty need to be provided with continuous support that includes appropriate technology, ongoing training, and technical assistance in making the transition to the online environment.

Recommendations

The results of this study substantiate previous research, which could benefit all stakeholders including learners, faculty members, and leaders in colleges and universities that offer online education. The results of this study provide the following recommendations for the practice of online teaching at institutions of higher education.

- Considering a learner-centered approach and experiential learning, online educators must re-conceptualize their roles and develop interpersonal relationships with their students. The key to success in online teaching is not only students’ knowledge acquisition but also their construction of a meaningful and rich experience.

- Online educators must be aware of social presence and fully integrate this concept into their practice. Their visibility in an online class plays a critical role in greater participation, teamwork, respect, and commitment from students.

- Online educators must instill a learner-centered learning environment in which students become empowered to take charge of their own learning and achieve greater learning outcomes.

- Online teaching requires more time and effort than face-to-face education. Administrators must assess and evaluate faculty workload, holding shared responsibility in creating the finest and most effective e-learning environment.

- The goal of online faculty development must go beyond remediation of deficient skills. Along with pre-existing skills, online educators must be provided with opportunities to build teaching strategies that promote active learning.

Suggestions for Future Research

Although diligent attempts have been made in this study to gain insight and practical knowledge about the experiences of educators who teach online, important information is still lacking. More research may be needed to substantiate the findings of this study. Additional research on the following topics could help to shape and enhance online teaching practice.

- This study should be replicated with similar faculty populations to determine the robustness and generality of the findings of this study.

- Research into personal characteristics or teaching styles should be conducted to find out if there are specific types that are better suited to teach online than in a face-to-face classroom.

- More research is needed in support of online faculty development programs. One study could be a set of modules based on the recommendations made in this study to evaluate its practicality and efficacy.

There are many questions to ponder, and the answers will continue to elude researchers for some time because the landscape of online teaching is still evolving as technology changes and becomes more omnipresent in education. Technology is developing so rapidly that it is nearly impossible to predict what innovations will emerge tomorrow. Researchers must accept this reality while exhibiting intellectual curiosity, tolerance for ambiguity, and a willingness to admit mistakes to provide sounder and more productive studies. As online teaching is still a new and growing area in academe, research efforts are likely to increase and continue .

|

References

Allen, K. (2005). Online learning: Constructivism and conversation as an approach to learning. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 42(3), 247-256.

Allen, E. L., & Seaman, F. (2007, October). Online nation: Five years of growth in online learning. Needham, MA: Sloan Foundation. Retrieved May 18, 2008, from http://www.sloan-c.org/publications/survey/pdf/online_nation.pdf

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2), 1-17.

Aragon, S. R. (2003). Creating social presence in online environments. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2003(100), 57-68.

Bull, G., Knezek, G., Roblyer, M. D., Schrum, L., & Thompson, A. (2005). A proactive approach to a research agenda for educational technology. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 37(3), 217-220.

Conceição , S. C. O. (2006). Faculty lived experiences in the online environment. Adult Education Quarterly, 57(1), 26-45.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education.The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 1-19.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence and computer conferencing in distance education.American Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 7-23.

Garrison, D. R., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: Interaction is not enough. Journal of Distance Education, 19(3), 133-148.

Gudea, S. F. W. (2005). Online teaching as experienced by teachers: A grounded theory perspective. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. The Claremont Graduate University. Claremont, CA.

Kim, K-J., & Bonk, C. J. (2006). The future of online teaching and learning in higher education. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 29(4), 22-30. Retrieved May 18, 2008, from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/EQM0644.pdf

Ko, S., & Rossen, S. (2004). Teaching online: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin .

Lao, T., & Gonzales, C. (2005). Understanding online learning through a qualitative description of professors and students’ experience. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 13(3). 459-474.

Lewis, T. O. (2007). The preparation of faculty to teach online: A qualitative approach. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA.

Lewis, C. C., & Abdul-Hamid, H. (2006). Implementing effective online teaching practices: Voices of exemplary faculty, Innovative Higher Education, 31(2), 83-98.

Lowenstein, A. J., & Bradshaw, M. J. (2004). Fuszard’s innovative teaching strategies in nursing (3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

Meyer, K. R. (2004). Disembodiment for the sake of convenience: An exploratory case study of student and faculty experiences and a nursing program's technology initiative. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of St. Thomas Minnesota. Saint Paul, MN.

Mykota, D., & Duncan, R. (2007). Learning characteristics as predictors of online social presence. Canadian Journal of Education, 30(1), 157-170.

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Oliver, C. (2004). Teaching at a distance: The online faculty work environment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. The City University of New York, NY.

Patton, M. Q. (2001). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Picciano, A. G. (2002). Beyond student perceptions: Issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 21-40.

Rovai, A. P., Ponton, M. K., Wighting, M. J., & Baker, J. D. (2007). A comparative analysis of student motivation in traditional classroom and e-learning courses. International Journal on E-Learning, 6(3), 413-432.

Ryan, M., Carlton, K. H., Ali, N. S. (2004). Reflections on the role of faculty in distance learning and changing pedagogies. Nursing Education Perspectives, 25(2), 73-80

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer.

Savery, J. R. (2005, Fall). BE VOCAL: Characteristics of successful online instructors. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 4(2), 141-152.

Schiffman, S., Vignare, K., & Geith, B. (2007). Why do higher-education institutions pursue online education? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(2), 61-71.

Short, J.A., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Swan, K., & Shih, L. F. (2005). On the nature and development of social presence in online course discussions. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks,9(3), 115-136.

Thompson, M. M. (2004, June). Faculty self-study research project: Examining the online workload. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 8(3), 84-88.

Tu, C. H., & McIsaac, M. S. (2002). The relationship of social presence and interaction in online classes. The American Journal of Distance Education, 16(3), 131-150.

Tu, C., Yen, C., Corry, M., & Ianacone, R. (2003). Collaborative evaluation of teaching. In G. Richards (Ed.). Proceedings of world conference on e-learning in corporate, government, healthcare, and higher education 2003 (pp. 325-330). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Turner, C. W. (2005). Voices of faculty and students: Exploring distance education at a state university. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM .

Uhlig, G. E. (2002). The present and future of distance learning. Education, 122, 670-673.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|