Introduction

The asynchronous discussion has become an important and widely-used component of online courses. Research indicates that these discussions foster learning when assessed using conventional exams (Althaus, 1997; Steimberg, et al., 2004; Webb et al., 2004; Wu & Hiltz, 2004) and student surveys (Dennen, 2005;Northrup, 2002; Swan, et al., 2000; Young & Norgard, 2006). Learning is dependent, however, on student participation, which can vary substantially depending on the format employed, the instructor’s participation, and student interest in the subject matter or question under consideration (Dennen, 2005; Northrup, 2002 ; Picciano, 2002; Ormrod, 2008; Vonderwell, et al, 2007; Wu & Hiltz, 2004).

The importance of generating student interest in online discussions is widely acknowledged and has been extensively studied (Andresen, 2009; Dennen, 2005; Northrup, 2002; Picciano, 2002 ), but relatively little research has been conducted to empirically test the hypothesis that there exists an optimal level of participation, which can readily be exceeded. It is recognized, nonetheless, that a vigorous discussion can add hours of work to an already heavy course load and potentially distract students from more important coursework. It is also understood that many students find pleasure in using technologies that allow for instant communication, and that some students may find it difficult to disengage from an online discussion in time to prevent it from becoming an undesirable distraction.

For some students, excessive Internet use is unquestionably a serious problem. It has been proposed, in fact, that “Internet addiction” be added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) (Block, 2008). One symptom of Internet addiction is excessive time devoted to Internet use. Unfortunately, little data has been published that can help instructors define normal and excessive rates of participation in asynchronous online discussions.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between participation in asynchronous discussions and course success in an entirely online environmental biology course. The data collected may prove helpful in determining the range of participation rates beneficial to learning and the point at which participation is likely to become excessive. Excessive participation defined, for the purposes of this study, as a level of participation that is extensive enough to interfere with learning, as measured by performance on a conventional final written exam.

Methods

Eighty-seven community college students, enrolled in an online environmental biology course during the 2008-09 academic year, participated in the study. Students ranged in age from approximately 17– 50. The ratio of male to female students approximated 1:2. Students that dropped the class prior to participating in any discussions were not counted as participants.

The same instructor taught three offerings of the course, using the same textbook, final exam, and course format. The course was built and administered on the Desire to Learn platform (versions 8.3.1 and 8.4.0).

Asynchronous discussions were initiated at the beginning of the 2nd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, and 15th weeks of the 16-week course. Threaded asynchronous discussions were adopted, in part, because research indicates the threaded asynchronous format encourages higher levels of participation than unthreaded and/or synchronous formats (Dennen, 2005; Vonderwell et al 2007).

Students were required to make a minimum of three “substantive” posts during each discussion. Additional posts were encouraged, but were not rewarded with additional points. The discussions were scheduled to run for one week. They were not formally closed, however, and activity in some discussions continued past the scheduled end date.

Research indicating that timely and substantive instructor feedback enhances student participation in online discussions (e.g., Dennen, 2005) was incorporated into the course. The instructor and several “peer-educators” monitored the discussions and attempted to enhance participation by asking for clarification, posting follow-up questions, and assuring that the majority of initial student posts received at least one reply. The peer-educators were students who had previously taken the course and volunteered to be discussion facilitators. The instructor read all discussion posts, attempted to clarify inaccurate statements that went unchallenged, and answered all questions directed at the instructor, in particular.

The instructor was mindful of research indicating that instructor participation can attenuate learner-learner interaction ( Guldberg and Pilkington, 2007; Paloff and Pratt, 2001) and generally allowed the discussions to develop for several days before becoming extensively involved. The peer-educators were also instructed to let the discussions develop.

An initial post was due by the third day of discussion. The remaining posts were due by the seventh day of discussion.

A post was considered “substantive” if, in the eyes of the instructor, it demonstrated an understanding of the subject and contained one or more of the following:

- Germane reference to a passage in the assigned reading, or an outside source.

- Important insight (e.g., an insight concerning the relationship of the question posed to another topic in environmental biology).

- Appropriate correction to another participant’s post.

- Thoughtful answer to a follow-up question from the instructor or a peer-educator.

- Related question of interest or concern.

“Substantive” was not defined in terms of word length, and some students earned full credit for participating in a discussion by posting fewer than 300 words. While it is impossible to identify a typical post and response, the following unedited example may be considered representative of a substantive post and proper response.

Question: What changes, if any, should be made with respect to U.S. energy policy?

Student’s Response: Kayla's idea of allowing each household a certain amount of energy in accordance to how many people are living under that roof sounds great hypothetically but I don't think it's practical because it will be impossible to determine the amount of energy one needs. If possible, I would rather make a policy that would mandate a certain limit of GHG each household can produce in a certain period of time. Also, Empire State Building has shown a very positive example with its $100 million "green" project which would reduce 38% of total energy consumption by the building saving $4.4 million every year on energy. I believe, In a city like New York where commercial buildings are responsible for 79% of carbon emissions, an energy policy that would require all the commercial buildings to implement "green" projects like that of Empire State Building would make a huge contribution towards developing renewable engergy and thus reducing GHG's.

Peer-Educator’s Response: Could we use a carbon tax to get others to follow the Empire State Building’s lead?

The following unedited response to the same question received only partial credit, and is fairly representative of those posts considered deficient: I am not sure that making laws is going to be the best idea. I believe it is important that people just make the effort to turn lights off, unplug unused appliances, and do more things outside that do not require as much energy if any. Laws would help but that takes away the freedom in America. I am afraid of a communist state.

The questions posed by the instructor were intended to be provocative and no “correct” answers were assumed to exist. Most of the questions concerned specific environmental policy decisions and all of the questions allowed for multiple perspectives and lines of argument. Such questions have been found to give students the greatest opportunity to engage in discussion (Andresen, 2009; Guldberg and Pilkington, 2007; Picciano, 2002).

The word count feature in Microsoft Word was used to count the number of words posted. No effort was made to edit contributions to the discussion prior to performing word counts. The D2L software program tabulated the number of posts opened by each student and the instructor tabulated the number of posts made by each student.

Learning was assessed using a comprehensive final exam. All students were administered the same final exam and were required to take the exam in a proctored setting. The instructor graded all exams. Names were withheld from the instructor until exam grading was completed.

The final exam took the following form:

- Multiple Choice Questions: 40 x 2 points each.

- Written Definitions: 7 x 3 points each.

- Short Essay Questions: 5 x 5 points each.

- Long Essay Questions: 2 x 15 points each.

The exam was worth a total of 156 points and accounted for 44.57% of the final grade (excluding a minor amount of extra credit).

In addition to the final exam, student course grades were based on online quiz results, position paper scores, discussion participation, and a small amount of extra credit. Final exam performance was chosen as the sole measure of learning achievement because the exam produced quantifiable results and was assumed to provide the most objective measure of success. Regression analysis showed that the final exam scores were quite closely correlated with the total number of points earned, minus the final exam score. The R2 value was .5725 (Ho P-value < .001).

Results

Twenty-six of the 87 students that participated in the study dropped the class after participating in at least one discussion, but prior to taking the final exam. There was a statistically significant difference in discussion participation rates (α = .05 ). Students that dropped the class averaged 349 words per discussion joined, while those that completed the class averaged 779 words. Ninety-five percent of those students averaging more than 500 words per discussion completed the course while only 47% of students contributing fewer than 500 words per discussion joined completed the course.

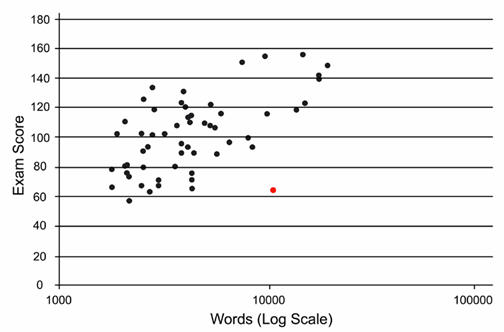

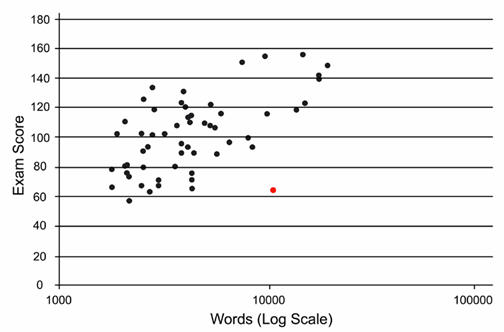

Participation rates for students that completed the course ranged from 1,716 words to 19,683 words. Final exam scores ranged from 58 to 156, with a mean of 101.3. See Figure 1. Gender differences were analyzed and male students were found to score somewhat higher on the final exam than predicted based on participation rates, but the difference was not statistically significant at α = 0.20.

Figure 1. Scatter plot of exam scores versus words posted.

Students that contributed more extensively to the discussions than their peers tended to open significantly more posts ( α = .05 ). The number of posts opened ranged from 18 to 4,490.

The data obtained by the authors were subjected to simple linear regression analysis to test for a relationship between participation rates and final exam scores. To address any deviations from normalcy in the distribution of test scores, the data were also evaluated via Spearman’s Rank Correlation. A statistically significant positive correlation was found to exist (p < 0.001 via regression analysis; p < 0.001 via SRC).

The relationship between discussion participation and final exam scores was evaluated using three different mathematical models: linear, logarithmic, and quadratic. All produced trendlines with positive slopes over the entire range of participation values encountered (p slope = 0 < 0.001). The line of best fit was determined for each model (See Table 1).

Participation, as measured by the number of words posted, was determined to account for 33% – 35% of the variance in test scores using all three models (i.e., 0.337 < R2 < 0.345). The R2 values increased to approximately 40% when the outlier at 10,551 words was removed (Red point in Figure 1.). This outlier was associated with a foreign student who made an unusual number of short posts expressing little more than agreement with her peers (e.g., “I was going to write something similar and think what you wrote is true.”). Other high-participation students tended to write longer, more substantive posts.

The critical point associated with the inverted U-shaped model (i.e., quadratic) was calculated via differential calculus and determined to be located at 27,778 words. This point represents the point where additional participation begins to detract from learning, if the assumptions of the model are valid.

Table 1. Regression equations and statistics for the linear, logarithmic, and quadratic models, respectively .

The Regression Equation |

sb |

se |

t

(df = 55) |

R2 |

F |

P |

ES = 0.0034w + 83 |

0.000639 |

21.0 |

5.29 |

0.337 |

27.98 |

<0.001 |

ES = 23.2 ln(w) – 93 |

4.32 |

20.9 |

5.38 |

0.345 |

28.94 |

<0.001 |

ES = -9x10-8 w2+ 0.005w + 79 |

0.191 |

21.0 |

5.35 |

0.342 |

28.58 |

<0.001 |

Discussion

The results obtained by the authors strongly support previous research findings concerning the pedagogical value of participation in asynchronous online discussions. Students that contributed little to the discussions (i.e., fewer than 500 words per discussion) were ten times more likely to not complete the course than their more involved peers. Students that completed the course, but contributed less to the discussions, also scored lower on the final exam than their more active peers. Unlike studies that failed to find a statistically significant correlation between discussion postings and performance on exams (e.g., Picciano, 2002), the results reported in this study were found to be statistically significant at alpha levels well below 0.05.

No evidence was found to support the hypothesis that high levels of participation in asynchronous online discussions can have a negative impact on learning. All three of the models used to evaluate the relationship between participation rates and final exam scores produced a best fit line with positive slope over the entire range of participation rates encountered. The significance of this finding must be judged relative to the range of participation rates encountered, which was substantial.

Students that completed the final exam contributed from 1,716–19,683 words during seven weeks of discussion. To put this range in perspective, 19,683 words equates to approximately 26 pages of single-spaced, 10-point, Arial font, on pages having 1.0” margins.

Students that averaged greater than 1,000 words per discussion also opened an average of 329 posts contributed by their peers. Assuming these students spent an average of just 2-3 minutes reading these posts, the highest discussion participants spent approximately 11-16.5 hours reading the contributions of their peers. They unquestionably spent several more hours composing and posting their own thoughts. These estimates are supported by the results of the course survey that was administered during the last week of class. Twenty percent of the students reported spending more than 12 hours per week on class activities. One noted that he spent in excess of 20 hours per week participating in the discussions.

A logarithmic model produced the highest R2 value, suggesting the relationship between participation, as measured by total word count, and achievement, as measured by final exam score, is one of diminishing returns over the range of counts observed. The differences in the R2 values associated with the models employed are small, however, and far from compelling.

The true nature of the relationship between discussion participation rates and learning is impossible to discern from the data collected. However, it can be reasonably assumed that participation becomes excessive and measurably counterproductive, with respect to exam performance, at some point. If it is further assumed that the relationship is characterized by an inverted U-shaped curve, this critical point can be estimated based on the line of best fit produced by the quadratic equation used to model the relationship in this study. This point occurs at 27,778 words.

Clearly, the above calculation rests on several questionable assumptions concerning the nature of the relationship between participation and learning, and the figure produced must be regarded as a very rough estimate. Any critical point that exists will, furthermore, vary across academic disciplines, courses, and institutions. The data from this study clearly suggests, however, that participation in asynchronous online discussions can be very robust (i.e., 2,800 – 4,000 words/week) without having a discernable negative impact on exam scores.

Although the authors found no evidence that robust participation in asynchronous discussions can harm student exam performance below 4,000 words posted per week, it is important to recognize that enthusiastic participation may have adverse effects that fall on the peers of the most active discussion participants. Some students may feel overwhelmed by the amount of information being posted by their peers, for instance, and respond by withdrawing from the discussions and/or the course (Palloff & Pratt, 1999). To address this concern, the authors believe it is important to let students know that they are not required to read every post. Instructors may also wish to flag particularly important posts for their students, or have their teaching assistants do so, if no limits are placed on participation.

Conclusions

The finding of a strong correlation between online discussion participation and exam performance is not surprising. Research indicates that students enrolled in courses demanding familiarity with a large number of subject-specific terms and concepts are likely to benefit from conceptual and subject-related online discussions (e.g., Kortemeyer, 2006). Because environmental biology students are commonly introduced to hundreds of unfamiliar terms and related concepts, participation in online discussions might reasonably be expected to be of exceptional and readily observable benefit. Certainly, the students who most actively participated in the above described discussions were disproportionately exposed to the terms and concepts that had to be mastered in order to do well on the final examination.

Excessive participation in online discussions may occasionally inhibit learning by drawing time away from other important course activities, but the risk of excessive participation appears to be very small in comparison to the benefits associated with robust participation. Instructors should certainly monitor the online discussions they initiate and make an effort to identify students that are spending an excessive amount of time in the discussion forum, or withdrawing from the discussion as a result of being overwhelmed. The authors do not recommend placing restrictions on participation, however. Internet addicted students are not likely to reduce their time on the Internet, and creating an interesting forum where students feel comfortable expressing their thoughts ad libitum clearly seems to promote success. The results of this study indicate that this is true both in terms of learning and course completion rates.