Introduction

It is an easy task to reflect back upon an

experience that was as positive as this was. It

began with apprehension, the first class I had

taken in many years, uncertainty about the

qualities of the materials and some indecision as

to wanting to dedicate the amount of time

necessary to make the process meaningful. It is

ending with a desire to continue. This has been a

rewarding experience and has been a benefit to my

role as teacher.

This was written by a 58-year old male student on

an end-of-course evaluation of an online graduate

course.

Literature Review

Information from the U.S. Census Bureau (2008)

reveals that the overall population in the United

States is aging, and their projections show that

in the next few decades the fastest growing

segment of the population will be older adults.

This holds true for the workforce as well, with

the number of workers over the age of 55

increasing at a higher rate than any other age

group (Alley & Crimmins, 2007). Additionally, we

know that our economy and workforce demand

life-long learners who continually update and

upgrade skills (Shen, Pitt-Catsouphes, & Smyer,

2007), and that late-career workers value

workplace lifelong learning (Fredericksen, 2006).

Despite the emergence of the “late-career

student,” there is scant research on the

educational needs and performance of students ages

50-65 in higher education (Paulson & Boeke, 2006).

Interestingly, the American Council on Education

recently published research results entitled

Reinvesting in the Third Age that identified

the need for higher education to focus more on

individuals aged 50 and older (Lakin, Mullane, &

Robinson, 2007 & 2008). Recommendations from this

focus group research suggested that older adults

prefer education “skill-ettes” (i.e., short,

specialized instruction focused on a particular

need) and colleges should learn more about the

interests and needs of this age group. This is

consistent with the finding that late-career

workers possessed positive attitudes toward

learning, but only if it was relevant and helped

them do their jobs better (Fuller & Unwin, 2006).

To compound matters, higher education is

experiencing a shift from traditional face-to-face

instruction to fully online courses (Grant &

Thornton, 2007; Rose, 2009). Online enrollment

continues to rise rapidly with over 20 percent of

students taking online courses (Allen & Seaman,

2008). It is expected that this shift in learning

modalities will become even more prevalent in the

next decade, so to maintain credentials and engage

in life-long learning, late-career adults will

have little choice but to attempt online

coursework. This online interaction is second

nature for digital natives (i.e., those who grew

up with computer technology), but it requires new

learning for digital immigrants (Prensky, 2001).

Additionally, this shift in instructional formats

implies that instructors must follow the process

of interaction design to create an effective

environment for diverse learners in their online

coursework (Preece, Rogers & Sharp, 2002; Tallent-Runnels,

Thomas, Lan, Cooper, Ahern, T.C., Shaw, et al.,

2006). To identify these learning needs,

instructors will need to conduct an analysis of

necessary technology support and assignment

options that match the learning styles of their

course participants.

While late-career adults are becoming more

technologically savvy, these digital immigrants

are still reluctant to take online coursework. In

2007, AARP reported that most adults (69%) aged 50

to 64 used the Internet; however, they rarely

participated in formalized online learning. When

asked why they did not participate in online

coursework, older adults most often cited poor

computer skills and loss of face-to-face

connections as the primary reasons (Lakin et al.,

2008). Contrary to the research, this study found

that more than a third of all students in the

online graduate course Introduction to

Transition Education and Services were

late-career adults. The characteristics of

the students aged 50 to 65 and their learning

outcomes from the course are the focus of this

study.

Methods

This study examined the learner characteristics,

academic performance, and satisfaction of

late-career teachers (aged 50-65) in an online

graduate course. Research questions included:

1.

Why did late-career adults choose to take this

online course?

2.

What level of content and technology knowledge did

participants have prior to the online course?

3.

How did late-career adults perform in this online

course?

4.

What level of technology support was necessary to

facilitate the learning of late-career adults in

the online environment?

5.

Were late-career adults satisfied with the online

course content and instructional methods?

Setting and Content

The asynchronous online graduate course,

Introduction to Transition Education & Services

was designed for secondary special educators who

support students with disabilities in high school.

The course was the first in a series of five

online graduate courses, each worth 1 graduate

credit hour (totaling 5 graduate credits) at a

Midwestern research university. Employing a cohort

model, course participants advanced through the

series together, with research-based interaction

design and instructional support components

embedded into each course. These included: (a) a

syllabus that outlined all assignments,

expectations, and due dates; (b) detailed

technical assistance instructions with screen

shots; (c) structured discussions with a rubric

posted on the course website; (d) a forum to post

course questions; (e) content and media options

that addressed a variety of learning styles; (f)

student choice in application activities that

related the content to their teaching; and (g) a

reflection and evaluation of the instruction and

learning experience that was used to continually

enhance the instruction and learning environment.

This standardized format enabled learners to

master the learning format during the first course

and then continue to use these newly-acquired

skills in the subsequent courses.

As the first course in the series, Introduction

to Transition Education & Services was offered

during the fall and summer semesters using the

open-source course management platform Moodle

(http://moodle.org/). One week prior to the start

date, students received access to the course and

login instructions so they could explore the

website freely. The course website provided

students the syllabus, grading rubric, information

about technical formats, and all necessary

resources needed for successful completion.

Students submitted all assignments on the course

website and e-mails could be sent to the

instructor through the website or via students’

personal e-mail accounts.

Participants

In 2007-2009, 136 graduate students completed

Introduction to Transition Education & Services.

Two state Departments of Education (one Midwestern

and one

Eastern State) offered limited stipends to high

school special education teachers in their state

who chose to take the course. The course was

customized with state-specific content for the

cohorts in these states. Other participants

enrolled online through the university’s

continuing education division and paid full

tuition. The results of this study reflect the

data from the seven cohorts of students who

participated in Introduction to Transition

Education & Services between 2007 and 2009

(see Table 1).

Table 1: Cohorts

|

Year |

Cohort |

Number of Students |

Percentage of Students aged 50 and above |

|

2007 |

State A, Cohort 1 |

17 |

53% |

|

2008 |

State A, Cohort 2 |

28 |

43% |

|

|

State B, Cohort 1 |

19 |

26% |

|

|

National, Cohort 1 |

13 |

46% |

|

2009 |

State A, Cohort 3 |

24 |

38% |

|

|

State B, Cohort 2 |

23 |

26% |

|

|

National, Cohort 2 |

12 |

33% |

|

Total |

|

136 |

38% (51 students) |

While the program did not intentionally recruit

late-career adults, 51 individuals aged 50-65

chose to enroll. These students were primarily

female (82%) and the majority held a master’s

degree or higher (67%). Job titles of these older

adults included: special education teacher (30),

transition specialist (7), related-services

provider (6), administrator (3), college faculty

(2), community agency consultant (2), and parent

of a child with a disability (1). Most of these

individuals had a long-term career in the field of

education (i.e., 74% for 10+ years, 16% for 7-9

years, 6% for 4-6 years, and 4% for 1-3 years).

Measures

Several quantitative and qualitative measures were

implemented throughout the online graduate course

to collect background information on the

participants and assess their change in knowledge,

attitude, and skill. Furthermore, data were

archived throughout the course to continually

improve the course content and instructional

strategies. These measures are described next.

Demographic Survey.

Prior to starting the course, participants

completed a survey that gathered demographic

information as well as their use of and comfort

with technology. Descriptive and comparative

analyses were used to develop a detailed picture

of the course participants.

Competency Survey.

The competency

survey was based on the transition specialist

indicators identified by the Council for

Exceptional Children’s Division on Career

Development and Transition (2000). Participants

were asked to rate their current aptitude on 40

indicators using a 4-point Likert scale. This

pre-assessment survey enabled course content to be

tailored to meet the needs of the participants.

Case-based Learning Pre/Post Assessment.

During the second week of the course, participants

completed a case-based learning experience on

transition education compliance and best practice

(Morningstar,

Gaumer Erickson, Lattin & Wade, 2008). This

learning experience utilized performance-based

assessments that required participants to apply

their learning to case study examples and their

own students. The pre/post assessment consisted of

a 20-item multiple-choice test on key points of

the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

(2004).

Satisfaction Survey.

After completing the case-based learning

component, participants were asked to rate their

satisfaction with the interactive content and

online learning in general on a 20-item survey

using a 5-point Likert scale. Questions on this

survey evaluated the time required to complete the

learning experience, comfort with technology,

components of the case-based learning experience

that were most beneficial, and future uses for the

information gained through the learning

experience.

Discussion Forums.

Asynchronous discussions were utilized during two

of the four weeks of the course. A topic in the

first week’s discussion asked participants to

introduce themselves and share their hopes and

concerns related to the course. In addition to the

week-long discussion, the instructor asked

participants to post their questions about course

content in a forum titled, “General Class

Questions.” This enabled the instructor to post

responses that could be accessed by all course

participants. For this study, discussions from

both Week 1 and General Class Questions

were analyzed. These qualitative data were

collected, printed, and coded to reveal themes

related to the comfort with technology and reasons

for pursuing the course. It was then quantified

revealing the number of posts for each course

participant related to the themes.

E-mail Communication.

All e-mail communication with the instructor was

archived. While many students posted their

questions to the General Class Questions

discussion forum, others felt more comfortable

sending an e-mail directly to the instructor.

These e-mails were coded through the same

procedure as described above for the discussion

forums.

Course Reflection.

During the last week of the course, participants

were asked to reflect on the course content.

Specifically they were asked to:

Write a 1-2 page single-spaced reflection on this

online learning experience. Be sure to identify:

(a) information, resources, & activities you found

most useful, (b) how you will use the information

to improve transition services in your school or

community, and (c) suggestions for improving this

online learning experience.

A random sample of twenty-five reflections from

participants aged 50-65 were coded and themed to

identify the course content that they found to be

most beneficial and the application activities

they planned to undertake based on their learning.

Additionally their suggestions for improving the

online experience were analyzed to identify

overarching support needs of this age group.

Quantitative data analyses consisted of

descriptive statistics (i.e., mean and standard

deviation), analysis of variance (ANOVA), and

paired-samples t tests. For all analyses,

the course participants were divided into three

groups (early-career participants aged 21-35;

mid-career participants aged 36-49; and

late-career participants aged 50-65). ANOVA

procedures evaluated the relationship between

factors and the dependent variable (e.g., the

relationship between technology skills and the age

of participants). Because each ANOVA included

variables with more than two levels, they were

followed with pairwise comparisons (i.e., Dunett’s

C if variances were unequal or the least

significant difference (LSD) procedure if

variances were not statistically different). A

paired-sample t test evaluated the

performance across time with two data points

(i.e., case-based instruction pre/post test

performance). The a priori level of 0.05 was set

for all statistical tests (Green & Salkind, 2003).

Results

Throughout the results section, course

participants are compared using three groups.

Those aged 50-65 are termed late-career; aged

36-49 termed mid-career; and aged 21-35 termed

early-career. Because the vast majority of

individuals who participated in the course were

practicing teachers, these employment terms

accurately represent the participants.

Why did late-career adults choose to take this

online course?

When asked why they chose to take the course,

late-career participants cited two main reasons:

1) their interest in the topic and 2) the ability

to earn recertification credits. As one student

noted, “I see the courses as a great opportunity

to learn knowledge and skills that will better

equip my students to meet their post-secondary

goals.” Others described the appealing layout,

“This seemed to be a good way to learn more about

the field in an efficient and timely manner” and

“I like the opportunity to gain new information in

a short period of time. I also like the intensive

focus on one topic at a time.”

What level of content and technology knowledge did

participants have prior to the course?

The subject-area competency was similar across all

age groups. When asked to rate competency on 40

transition-related skills, the mean scores of

late-career participants ranged from 1.90 (not

prepared) to 3.70 (very prepared), with an average

rating of 2.5 (somewhat prepared). This was

similar to their mid- and early-career

counterparts. These means reveal that on average

the course participants, regardless of their age,

felt that they had a moderate level of competency

related to the course content prior to enrolling

in the course (see Table 2).

Thirteen of the 51 late-career adults (25%) had

previously completed an online course. A one-way

analysis of variance was conducted to evaluate the

relationship between the number of online courses

taken and age of the student. Error rates on

follow-up analyses were controlled for using the

LSD approach. These analyses found that previous

online course-taking of late-career participants

was significantly lower than the online

course-taking of early-career participants (see

Table 2). The online course-taking for mid-career

participants was between that of early- and

late-career participants and thus not

statistically different from either group.

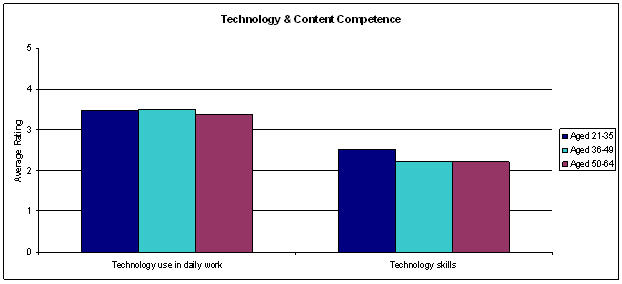

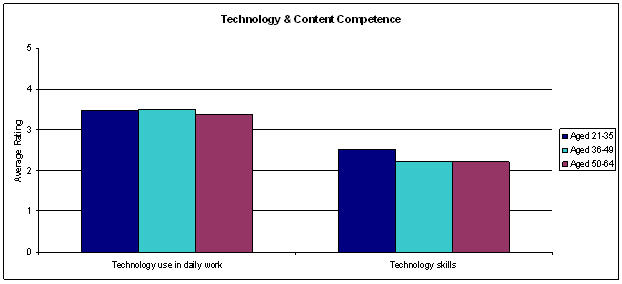

Late-career adults identified having a moderate

level of technology skills and used technology

moderately in their daily work. While their

technology usage rated at the same level as early-

and mid-career participants, the mid- and

late-career participants felt less experienced

technologically than the early-career participants

(see Figure 1). A one-way analysis of variance was

conducted to evaluate the relationship between

technology skills and age of the student. Because

Levene’s test found that equal variance could not

be assumed, error rates on follow-up analyses were

controlled for using the Dunnett C approach. There

was no statistical difference between the

technology skills of mid- and late-career

participants, but both groups rated their

technology skills statistically lower than the

early-career participants (see Table 2).

Figure 1: Technology Use and Skill

How did late-career adults perform in this online

course?

Late-career adults had high levels of success in

this online course. All (100%) late-career

participants successfully completed the course

requirements. Students receiving graduate credit

were graded on an A-F system with 22 earning an A

(90-100%) and 2 earning a B (80-89%). Other

participants chose to earn Continuing Education

Units (CEUs) with a pass/fail system through which

the remaining 27 participants earned a passing

grade.

The case-base learning pre/post assessment

reinforced the data from the competency survey

that identified similar levels of proficiency in

the subject area for all age groups. On the

pre-test, late-career participants averaged 62%

and increased their scores to 80% on the

post-test. No significant differences were found

in either the pre- or post-test scores when

compared to their younger counterparts. A

paired-samples t-test was conducted to evaluate

the increase in knowledge from the pre-test to the

post-test. The results for late-career

participants indicated that the mean score on the

post-test (M=80.42, SD=11.56) was significantly

higher than the mean score on the pre-test

(M=61.59, SD=15.57). Results for mid- and

early-career participants also showed significant

increases in knowledge.

What level of technology support was necessary to

facilitate the learning of late-career adults in

the online environment?

The discussion forum and e-mail analyses revealed

that students aged 50-65 ask more

technology-related questions than their younger

counterparts. These questions included asking for

directions regarding posting comments, submitting

assignments, and accessing online resources.

Approximately 40% of the late-career adults asked

a technology-related question. An ANOVA followed

by a Dunett’s C test revealed that late-career

participants asked significantly more

technology-related questions than early-career

participants. Results for mid-career participants

were not significantly different from either of

the other age groups (see Table 2). Other

discussion forum and e-mail analyses did not

reveal significant differences among the age

groups. The themes included asking course content

questions, expanding learning by discussing other

transition-related topics, and providing

technology-related support to peers on the

discussion forums.

Were late-career adults satisfied with the online

course content and instructional methods?

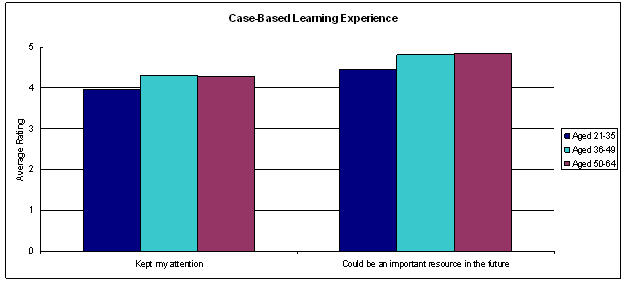

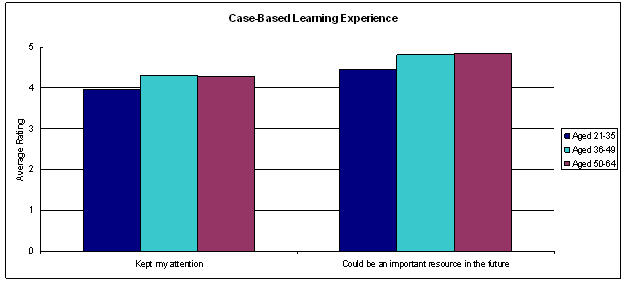

Some variance was identified among the age groups

on the satisfaction survey. Late-career

participants spent more time completing the

case-based learning experience, but they also gave

higher ratings to the following statements: (a)

the case-based learning experience kept my

attention and interest; and (b) the case-based

learning experience could be an important resource

to me in the future. These items on the

satisfaction survey were analyzed using a one-way

analysis of variance. Post-hoc procedures included

the LSD approach when variance was assumed (i.e.,

the case-based learning experience kept my

attention and interest) and the Dunnet’s C

approach when variance could not be assumed (i.e.,

the case-based learning experience could be an

important resource to me in the future). The

analyses revealed that the ratings of mid- and

late-career participants were significantly higher

than those of early-career participants when asked

if the case-based learning experience kept their

attention. On the item that asked if the

case-based learning experience could be an

important resource in the future, the ratings of

late-career participants were significantly higher

than those of early-career participants. The

ratings of mid-career participants fell between

the early- and late-career participants, and thus

were not statistically different from either group

(see Figure 2). Table 2 provides mean scores,

standard deviations, and p-values.

Figure 2: Satisfaction with Case-Based Learning

Experience

Upon completion of the course, participants were

asked to reflect on the course content. These

reflections revealed that participants aged 50-65

highly valued the applicability of the course

content to their jobs and the array of resources

provided throughout the course. All late-career

participants sampled identified the resources

(articles, videos, and website) as contributing to

their learning. Most also felt that the case-based

learning experience (76%) and discussions (68%)

were beneficial. These participants expanded on

the information by identifying ways they would use

their newly-acquired knowledge. Responses included

disseminating information to colleagues and

parents, improving the transition education

processes for students, and advocating for

increased collaboration and additional services in

schools.

“I have been utilizing what I have learned as I

have assisted students in their transition

planning. It has been invaluable, enriching

experience. I have allowed the students to take

more control so they feel more confident.”

“I have printed out the articles and some of the

information from the websites, and have

incorporated them into a note book with

information that can be used in the transition

planning process. I have also notified my

colleagues that I have this information, which

will be located in our special education

office/library. I have also e-mailed a list of

websites to them.”

“I would also like to begin sending out brochures

to parents or guardians before the IEP

[Individualized

Education Program] meetings so that they

come to the meetings better informed.”

“I actually called my Special Education Director

to tell her, ‘This is the first time transition

goals for a student felt individualized and

real!’”

“My e-mail has been busy sending new and seasoned

special educators in the school bits and pieces of

this class.”

“I am already using the information garnered in

this course in my IEP meetings.”

When asked how they would improve the online

learning experience, half of the late-career

adults (50%) reiterated their satisfaction with

the course. Others identified technology, time

commitment, and discussion forum strategies.

“As to areas of improvement, my more traditional

habits of learning cause me to seek out more topic

specific discussion forums.”

“Time commitment to do the activities continues to

be a concern to me, but the information is

invaluable.”

“The lack of programs to view some of the videos

is a bummer but being able to read the text is

some consolation.”

Overall late-career adults came into the course

with moderate levels of prior knowledge and showed

stellar performance on all assignments. They

required higher levels of technology support, but

once they became proficient in the technology

requirements, they found the course content and

format to be highly beneficial and applicable to

their work. This satisfaction was evident in the

enrollment rate of the next course with 94% of the

late-career participants in the Introduction to

Transition course enrolling in the second

online course in the series.

Discussion & Implications

The course was not designed for or specifically

marketed to late-career adults, but many

individuals chose it as their first online

learning experience. While one study found that

25% of teachers in the

United States

are over the age of 50, 38% of participants in

this online course were in that demographic

(Miller, Sen, Malley, & Burns, 2009). This

reaffirms research that older adults prefer highly

specific, short-term learning opportunities based

on their interests and job requirements (Fuller &

Unwin, 2006; Lakin et al., 2008; Shen et al.,

2007; Tallant-Runnels, Thomas, et. al., 2006).

Teacher re-certification requirements and employer

expectations also encouraged participation in this

professional development opportunity. Teachers

must participate in professional development

throughout their teaching career, but they

typically have extensive flexibility in the

professional development options they choose,

including school and district in-services,

workshops, conferences, and coursework (National

Center for Education Statistics, 1999). All course

participants could have met re-certification

requirements without participating in online

training, but it is unlikely that face-to-face

training options would have been as specialized as

that provided in this course. While the teacher

re-certification requirements should be considered

when generalizing the results of this study, it’s

important to note that this online course was

sought out specifically by late-career teachers to

meet these requirements.

These late-career adults used technology for their

work (primarily teaching) at similar levels as

their younger colleagues, but they reported that

they did not feel as skilled in technology use.

This was substantiated by both their self-ratings

of technology skills and use, as well as the

number of technology-related questions posed

during the course. While many of the late-career

adults entered the course concerned about their

technology skills, they were willing to work

through the barriers with the instructor because

they valued the information. This interaction

required higher levels of “invisible” labor by the

instructor (Blair & Hoy, 2006), but it also

produced an online learning community that

extended the learning opportunities within the

course (Grant & Thornton, 2007).

Table 2: Performance and Perception by Age Group

|

|

Participants

Aged 21-35 |

Participants

Aged 36-49 |

Participants

Aged 50-64 |

|

|

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

p |

|

Number of online courses

|

2.12 |

2.01 |

1.28 |

1.85 |

1.12 |

1.79 |

0.05 |

|

Technology use in daily work |

3.48 |

0.51 |

3.50 |

0.51 |

3.36 |

0.53 |

0.37 |

|

Technology skills

|

2.52 |

0.51 |

2.20 |

0.69 |

2.20 |

0.49 |

0.03 |

|

Subject-area competency

|

2.53 |

0.39 |

2.55 |

0.42 |

2.50 |

0.30 |

0.83 |

|

Satisfaction – Case-based learning experience

kept my attention |

3.97 |

0.73 |

4.30 |

0.61 |

4.28 |

0.57 |

0.05 |

|

Satisfaction – Case-based learning experience

could be an important resource in the future |

4.45 |

0.83 |

4.80 |

0.41 |

4.84 |

0.37 |

0.01 |

|

Number of technology-related questions |

0.17 |

0.45 |

0.49 |

0.84 |

0.88 |

1.51 |

0.01 |

It is interesting to note that late-career adults

gave higher satisfaction scores to some components

of the course, specifically the case-based

learning experience that required participants to

read research-based content and then apply the

information to case study examples. Hypotheses for

these higher ratings could be that digital

immigrants have a high appreciation for content

that is directly applicable to their jobs or that

digital natives expect more active interfaces

(i.e., game-like atmospheres) in online

environments (Zemke, Raines & Filipczak, 2001). In

addition, the case-base learning followed a

standardized format with a balance of content and

application. This “learning-while-applying”

approach has been found to be effective for

late-career learners (Charness, Czaja, & Sharit,

2007, pp. 233).

Additional research is needed on the perceptions

and performance of late-career adults in online

learning environments. Because these individuals

prefer highly specialized courses, additional data

need to be collected by institutes of higher

education on their continuing education course

participants. Older adults are continuing to grow

as a market niche in education, so to maintain a

competitive edge, institutes must identify the

needs, interests, and necessary online supports of

this age group.

Institutions of higher education should reflect on

their online course content and delivery systems.

The course in this study was unique in that it was

completed over a four-week duration. Additionally,

it was content-specific with direct application to

the job requirements of the participants. This

level of specificity and application was found to

be highly valued by late-career adults. As

institutions of higher education expand their

online course offerings, they should undergo a

rigorous evaluation process addressing the

context, interactions, and desired outcomes for

students (Preece et al., 2002; Ruhe & Zumbo, 2009;

Scanlon, Jones, Barnard, Thompson, & Calder,

2000). Foresight in course design can then lead to

higher levels of learning for individuals of all

ages.

Finally, the “invisible” labor of faculty teaching

online courses must be understood and valued. When

the instructor of the course in this study was

asked about instructional time, she responded:

Even after teaching this course seven times, it

still requires more of my time than any

face-to-face course I teach. In addition to

updating assignments and grading, I access the

course at least five days per week to respond in

weekly discussions and to answer questions from

students. Once students understand the course

layout and technology requirements, my

instructional time decreases substantially in the

four courses that follow Introduction to

Transition Education & Services.

This is aligned with research that identifies

student-staff contact and prompt feedback as core

principles in effective online teaching (Grant &

Thornton, 2007; Stein & Glazer, 2003). Many

students, especially late-career students, could

benefit from an introductory course that exposes

them to the online learning environment and

subject-area content prior to participating in

advanced online courses.