Balancing Quality and Workload in Asynchronous Online Discussions: A Win-Win

Approach for Students and Instructors

|

Zvi Goldman

Post University

Waterbury, CT 06723 USA

zgoldman@post.edu

Abstract

The challenge addressed in this article is how to achieve a win-win balance between quality and workload for students and instructors participating in asynchronous online discussions. A Discussion Guideline document including minimum requirements and best practices was developed to address this need. The approach covers three phases: design and development, setting up expectations, and launch and management. The goals of the approach, based on a commitment shared by all full time and adjunct faculty, are high quality of education as well as retention of both students and qualified instructors.

Key Words: Adult Online Education, Asynchronous Discussion, Course Workload, Best Practices |

Introduction and Challenge

Student engagement with instructor and peers in online education, specifically over multiple discussion group sessions, is a critical factor that contributes to student learning, satisfaction, course success, and retention (Bedi 2008; Bocchi, Eastman, & Swift, 2004; Mandernach, Dailey-Hebert, & Donnelli-Sallee, 2007). Valuable and productive online discussions are not serendipitous; they need to be carefully designed and developed, communicated to students in order to convey expectations, and launched and managed (Chen, Wang, & Hung, 2009; Wang & Chen, 2008).

In many institutions the phases of designing and developing (selection of topics and delivery structures) and setting expectations (communication of requirements to students and instructors) are implemented by course designers and/or full time faculty members responsible for this task. The launching and managing phase (daily/weekly management, presence and grading of discussion sessions) is typically the responsibility of the course instructor. The focus of this article is asynchronous online discussion in the context of an accelerated Masters of Business Administration (MBA) program designed for adult practitioners.

When discussions are regarded as critical components of learning, and administered as such, they impose a significant workload on both students and instructors. In applicable programs targeting practitioner adults, discussion sessions, during which much of the evidence-based learning and experience sharing occur, can easily consume half the course workload (Goldman, 2010). The reality is that neither students nor instructors can afford to dedicate an unlimited amount of time to fulfill course requirements or teach a course. Therefore, as a matter of practicality, discussion sessions should be carefully implemented to balance pedagogic quality and workload for students and instructors alike.

The challenge is how to achieve a win-win balance between discussion quality and workload for students and instructors. At stake is the quality of education on the one hand and retention of both students and qualified instructors on the other. Overly demanding discussion sessions might discourage students and instructors, while underperforming discussion sessions might not deliver on course objectives.

The approach taken at Post University's online MBA program to meet the above challenge was inclusive and collaborative, involving a commitment shared by all teaching faculty, full-time members and adjuncts. A Discussion Guideline document, including minimum requirements and best practices was introduced which covered three phases: design and development, setting up expectations, and launch and management.

Literature Review

Since the specific topic of this paper has not yet been explored, the literature review is limited to studies that address elements related to the topic, namely discussion guidelines and best practices for online courses (Hammond, 2005; Hanover Research Council, 2009; Thompson, 2010), faculty workload implications (Conceição & Baldor, 2009), and the relationship between course workload and quality of online education (Scheuermann, 2005, part I & II).

In a presentation at a 2010 Sloan-C conference, Thompson (2010) offered a summary of an assortment of best practices for online discussions based on student feedback and a literature review. The recommended best practices included strategies to nurture a social context to the discussion, control the level of instructor engagement and student participation, and facilitate and evolve the discussion.

A more systematic view that divided the best practice expectations into phases of design and development, instructor teaching, and expectations of learners was reviewed earlier by the Hanover Research Council (2009) and Hammond (2005). No attempt was made by any of the referenced sources to prioritize the guidelines into 'must have' and 'nice to have', or examine their workload impact.

Conceição and Baldor (2009) suggested practical ways to overcome workload-related faculty barriers to online teaching. Among the activities addressed were: designing and organizing the content, course management, and teaching practices. The authors recognized the need for further debate on how to balance "faculty workload and institutional support." The discussions of workload issues were not linked to the quality and value of online education or presented relative to both instructors and learners.

In a brief interview, Scheuermann (2005) commented on the relationship between the instructor's workload and the quality of online discussions, and suggested a few design and management strategies to maintain both. The following strategies were mentioned: manage the level of instructor participation and presence, evolve and grow the discussion with secondary/related topics, allow students to initiate discussions on related topics, and ask students for feedback and evaluation. The balance of workload and quality for students was not addressed or related to the instructor's workload.

The purpose of the present study is to offer an integrated approach which attempts to balance discussion workload and quality in online asynchronous discussions for both students and instructors, approach not addressed in previous studies.

Approach and Solution

a. Discussion - Guideline Goals The primary goal of the Discussion Guideline document is to help implement an optimal balance between learning experience, quality, and workload for all involved. Additional goals are:

-

Achieve program consistency: institute a single reference guideline throughout the program, common to all teaching staff and students.

-

Support a culture of excellence and continuous improvement: encourage all to develop and share best practices to harness the practical experience of the entire teaching staff.

b.

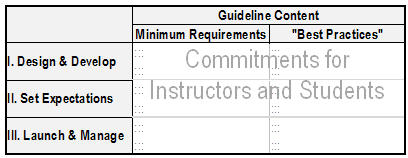

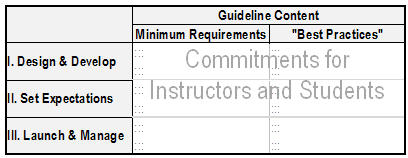

Discussion - Guideline Structure The content of the Discussion Guideline document is divided into three sections: design and development, setting up expectations, and launch and management, as shown in Figure 1. The design and development section addresses the design of discussion topics as integral components of teaching units to promote student engagement, sharing, and learning. The setting up expectations section addresses communication to students regarding emphasis on discussion and instructor’s commitment, expectations, and grading. The launch and management section demonstrates instructor presence, involvement, and delivery of end-value to students. The guideline content is comprised of minimum requirements and best practices recommendations. Minimum requirements are the required minimum standards and actions of all instructors, which promote all of the Discussion Guideline’s goals. Best practices are tested practices and behaviors, which exceed the minimum requirements and further promote all of the Guideline’s goals.

Figure 1. Content of the Discussion Guideline document

c. Discussion - Guideline Minimum Requirements

Design and development phase: Design discussion topics as integral components of the teaching units to promote student engagement, sharing and learning. Practice the following:

Install a non-graded thread for non-course-related communication. |

Develop 2-4 discussion threads for each week. |

Include threads for general questions at critical junctures of the course. |

Integrate discussion topics related to or reflective of concurrently addressed weekly content. |

Design many evidence-based discussions (supported by students' experience and/or research). |

Articulate the topics to promote critical thinking and argumentation. |

Allocate at least 25 percent of the total course grade to discussions. |

Include the discussion grading rubrics based on the expectations below in the syllabus. |

|

Setting up expectations phase : Communicate to students the emphasis on discussion and clarify instructor’s commitment, expectations, and grading approach. Inform students of the following expectations (in course information and announcements):

Read all postings. |

Start posting within three days of topic posting on each weekly discussion thread. |

Show substantive presence on discussions at least three days a week. |

Respond to the original/seed question and all other questions directly addressed to student. |

Post at least four substantive contributions on each discussion thread. |

Offer evidence-based support (of own experience and/or cited research) at least once per thread. |

Demonstrate course knowledge and critical thinking. |

Apply normative/proper English and grammar (no texting or abbreviations). |

|

Launch and management phase: Manage discussions to demonstrate presence, care and value, and practice the following:

Greet students during the first discussion week and facilitate introductions. |

Respond to all questions addressed to the instructor within 24 hours. |

Draw lagging students in and inform student advisors of no-shows (missing a week of discussions). |

Acknowledge individuals with notable contributions and interrupt/stop improper/unprofessional online behaviors. |

Manage the discussion quality to benefit all students - discourage superficial comments and irrelevant postings. |

Direct, facilitate, evolve and maintain the discussions to focus on stated weekly objectives (Limit serendipitous discussions to be contained within course objectives). |

Show substantive presence (facilitative, informative/teaching, and social) at least four days a week, including one week-end day. |

Challenge students to think deeper, differently and critically. |

Share your own knowledge and experience in measure (teach, don't control the discussion). |

Identify and manage (off-line) students with sub-par language skills. |

Grade discussions by the third day of the following week. |

Report to faculty in charge on important issues (no-shows, plagiarism, failed discussion topic, misconduct, etc.) |

|

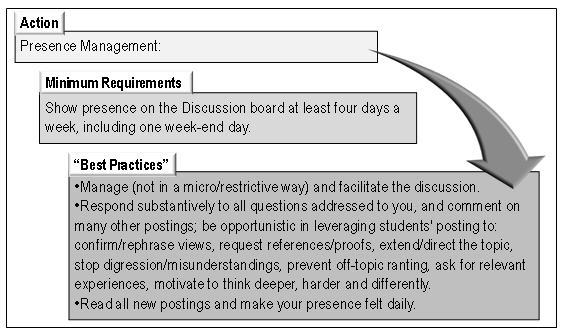

d. Illustration of Best Practices

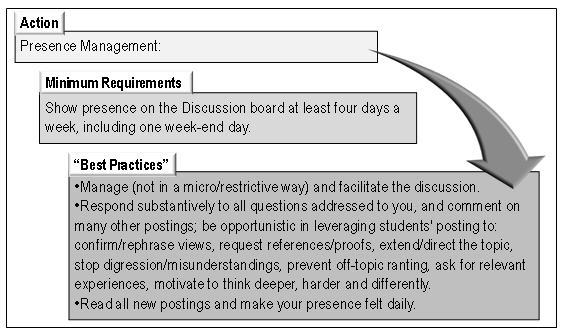

The complete list of best practices is available in Appendix A. Figure 2 illustrates how a set of best practices is associated with one of the minimum requirements for the launch and management phase. Each minimum requirement may be associated with many best practices that have been adopted by at least one instructor.

The exemplified minimum requirement item is "Show substantive presence (facilitative, informative/teaching, and social) at least four days a week, including one week-end day." The instructor's presence should include teaching, informative and social aspects. The best practice, supported by students' comments and feedback, indicates that it may not be best to administer all of these within the 'business' discussion threads. Attempting to do this may present a challenge in maintaining educational value and quality versus social interactions. Instead, additional and ongoing non-course objectives-related threads should be established and monitored.

Discussion

The purpose of the Discussion Guideline document's minimum requirements proposed in this article is to engage students and facilitate learning and critical thinking through evidence-based sharing of research and experience. The listed minimum requirements are in line with many other suggested discussion guidelines and best practices, emphasizing a high level of facilitation and engagement (Bruning, 2005; Kienle & Ritterskamp, 2007; Murchu & Muirhead, 2005; Shea, Li, Swan & Pickett, 2005; Spatariu, Quinn & Hartley, 2007; Walker, 2005).

Figure 2. How a set of best practices is associated with one of the minimum requirements for the launch and management phase.

Figure 2. How a set of best practices is associated with one of the minimum requirements for the launch and management phase.

Implementation of the above approach occurred as a direct result of requests from both students and instructors to ensure that time spent on discussions be productive and valuable. This common request was not surprising given commonalities between the instructors and adult students in this program, namely that most are practicing professionals who need to balance work, social/family life and education (see Appendix B for details). As the adult online education segment for students within the 25-40 years old age range is projected to grow faster than others (Magda, 2010), institutionalizing the 'engagement rules' for the balance between quality and workload will only increase in importance and visibility.

The demanding workload involved in online education is somewhat mitigated by the flexibility of the asynchronous teaching model. Practitioner instructors and students can choose the time of day to engage in the discussion. To meet the busy schedules of both adult students and instructors, structured engagement is practical and manageable for all involved. The minimum requirements should define and establish the workload expected of both instructors and students. Based on this, the retention and development of teaching staff should be more straightforward and easier for the governing institution. Also, as indicated in the Introduction section, student satisfaction and retention (impacted by quality and structured engagements) should also be positively affected by having minimum requirements set in place.

It is necessary, however, to recognize that the issue of student retention is complicated and involved, extending beyond course or discussion engagement alone. All student contacts with the teaching institution must be harmonized and integrated to optimize the learning experience and produce students who are vested in the process (Hill, 2009). Substantive asynchronous discussion, as exercised here and elsewhere, is not the only valid approach to improve online learning and student retention. Although high engagement is generally perceived to be beneficial (Kelly, 2009), the improvement of learning outcomes and student retention can certainly be achieved through other means as well (i.e. frequent announcements, innovative assignments, group projects, etc.).

Any set of minimum requirements has the potential to be too restrictive, limiting the free flow of opportune ideas and participation. On the other hand, adult students and instructors expect that course objectives will be satisfied in an efficient manner; discussion quality and workload should be balanced and discussion content and style should be conducive to achieving this outcome. Further, to meet the busy schedules of both adult students and instructors, a structured engagement governed by a minimal requirement set seems practical and manageable for all involved. The degree to which the minimum requirements and the overall Discussion Guideline document approach proposed in this article accomplish the desired balance between quality and workload is in the process of being assessed, as discussed below.

Conclusions and Next Step

The Discussion Guideline document proposed here is in line with the many, previously suggested online discussion 'rules'. The collaborative and integrated approach of required minimum requirements and suggested best practices is the essence of the present paper. The proposed approach of the Discussion Guideline document amounts to a necessary 'professional/courteous governance agreement' between all adult stakeholders sharing the class, instructors and students. The win-win outcome of this Discussion Guideline document approach should be measured by value perception, satisfaction and retention of students and instructors.

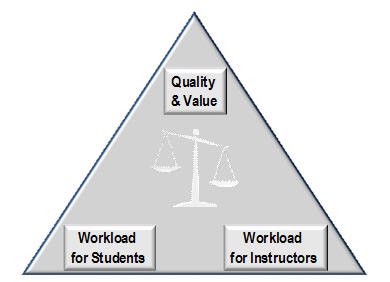

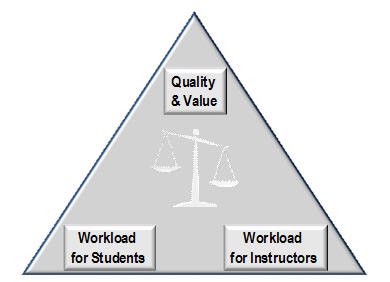

The Discussion Guideline document approach proposed here attempts to balance discussion workload and quality in asynchronous online discussions for both students and instructors. This approach seems to be missing from the public debate and is the focus of the present article. The follow-up to this approach, including the monitoring of the balance between quality and workload is ongoing. Adjustments to the implemented guideline will be introduced if and when they are necessary. Surveyed data of perceived discussion workload and quality from instructors and students will be presented in a future article. Data are being analyzed according to structure shown in Figure 3. The aim is to identify a 'sweet spot' of perceived quality for students and instructors under reasonable workloads.

Figure 3. Structure under which data are being analyzed.

Acknowledgments

The minimum requirements were collaboratively developed by the entire full-time faculty of Post University online MBA. Best practices contributions were made by the entire teaching staff.

References

Bedi, K., (2008). Best practices of faculty in facilitating online asynchronous discussions for higher student satisfaction. U21Global Working Paper Series, No. 005/2008.

Bocchi, J., Eastman, J. K., & Swift, C. O. (2004). Retaining the online learner: Profile of students in an online MBA program and implications for teaching them. Journal of Education for Business, March/ April, 245-253.

Bruning, K. (2005). The role of critical thinking in the online learning environment. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(5), 21-31.

Chen, D., Wang, Y., & Hung, D. (2009). A Journey on Refining Rules for Online Discussions: Implications for the Design of Learning Management Systems. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, v20 n2, 157-173.

Conceicao, S, & Baldor, J. (2009). Faculty Workload for Online Instruction: Individual Barriers and Institutional Challenges. Presented at the Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, Community and Extension Education, Northeastern Illinois University, Chicago, IL, October 21-23.

Goldman, Z. (2010). An Online Discussion Forum Guideline: Win-Win-Win for Students, Instructors and the University. Presented at the 16th Sloan-C International Conference on Online Learning. November 3-5, Orlando Florida.

Hammond, M. (2005, October). A review of recent papers on online discussion in teaching and learning in higher education. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(3), 9-23.

Hanover Research Council - Academy Administration Practice (2009). Best Practices in Online Teaching Strategies.

Hill C., Editor (2009). Strategies for Increasing Online Student Retention and Satisfaction. Faculty Focus Special Report.

Kelly R., Editor (2009). Synchronous and Asynchronous Learning Tools: 15 Strategies for Engaging Online Students Using Real-time Chat, Threaded Discussions and Blogs. Faculty Focus Special Report.

Kelly R., Editor (2009). Strategies for Increasing Online Student Retention and Satisfaction. Faculty Focus Special Report.

Kienle, A., & Ritterskamp, C. (2007). Facilitating asynchronous discussions in learning communities: The impact of moderation strategies. Behaviour & Information Technology, 26(1), 73–80.

Magda, A. (2010), Eduventures. Trends, Forecasts, Implications; The Adult and Online Higher Education Market. Presented at the 16th Sloan-C International Conference on Online Learning. November 3-5, Orlando Florida.

Mandernach, J., Dailey-Hebert, A., & Donnelli-Sallee, E. (2007). Frequency and Time Investment of Instructors' Participation in Threaded Discussions in the Online Classroom. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 6 (1), 1-9.

Murchu, D., & Muirhead, B. (2005). Insights into promoting critical thinking in online classes. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(6), 3-18.

Scheuermann, M. (2005). Course Quality and Instructor Workload : Pt. 2. Distance Education Report, 9 (2), 4-6.

Scheuermann, M. (2005). Course Quality and Instructor Workload : Pt. 1. Distance Education Report, 9 (1), 4-7.

Shea, P., Li, C. S., Swan, K., & Pickett, A. (2005). Developing learning community in online asynchronous college courses: The role of teaching presence. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 9(4), 59-82.

Conceição, S. & Baldor, M. J. (2009). Faculty Workload for Online Instruction: Individual Barriers and Institutional Challenges. Presented at the Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, Community and Extension Education, Northeastern Illinois University, Chicago, IL, October 21-23.

Spatariu, A., Quinn, L., & Hartley, K. (2007). A Review of Research on Factors that Impact Aspects of Online Discussions Quality. Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 51 (3), 44-45.

Thompson, J. (2010). Best Practices in Online Discussions: Insights From 10 Years' Experience Teaching Online Courses. Presented at the 16th Sloan-C International Conference on Online Learning. November 3-5, Orlando Florida.

Walker, G. (2005). Critical thinking in asynchronous discussions. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(6).

Wang, Y., & Chen, V. (2008). Essential Elements in Designing Online Discussions to Promote Cognitive Presence - A Practical Experience. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12 (3-4).

Appendix A

Best Practices

Minimum Requirements |

Best Practices |

Develop & develop the discussion topics and questions |

Install a non-graded thread for non-course-related communication. |

Provide student with an outlet to communicate about the program in general and other topics of their choice. This forum still needs to be monitored by the instructor. |

Develop 2-4 discussion threads for each week (seed questions). |

Balance the overall weekly course workload; design for more/fewer discussion threads on lighter/heavier weekly loads. Map/plan the discussions for the entire class in advance. |

- Include threads for general questions at critical junctures of the course.

- Integrate discussion topics related to or reflective of concurrently addressed weekly content.

|

The discussion topics could specifically complement issues from the current or most recent week, reflect on knowledge integrated so far during the course, or, set the stage/mindset for a follow-up assignment (reading or project). Vary slightly the nature and workload of the discussion throughout the course including focused explorations, integrated questions and reflective summaries. Design follow-up questions to further engage students along the progression above. Clearly state the relevance of all discussion questions. Use discussion topics from the master course and consult with the responsible full-time faculty when you wish to deploy better topics/questions. |

Design for many evidence-based discussions (supported by students’ own experience and/or research). |

Students should be encouraged to share their own experience, conduct research, and substantiate their major points. Design for about one hour of work to respond to each original/seed question. |

Articulate the topics to promote critical thinking and argumentation. |

Design the discussion thread to evolve from responding to the original seed question and immediate follow-ups, to expressing views, referencing ideas, responding to peers, and offering own experience. Ask open-ended questions to stimulate critical and 'out of the box' thinking, and carry the discussion to necessary directions and depths. Set the conduct rules for collegial argumentation. Some topics call for a healthy and formal debate: Develop 'role playing' and group collaboration exercises (mock trials, etc.). |

Allocate at least 25 percent of the total course grade to discussions. |

A range of 25-40 percent should be suitable for most courses. Capstone (i.e. heavy writing, self-executed projects) may not need such high emphasis on discussions. |

Include on syllabus the discussion grading rubrics based on the expectations below. |

Plan to communicate extensively the discussion expectations and grading policies in the syllabus, general course information space, and introductory announcements. |

Set up expectations for discussions with students |

Inform students of the following expectations (in Course Information and Announcements):

- Read all postings.

- Start posting no later than the third day into the week on each weekly discussion thread.

- Show substantive presence on discussions at least three days a week.

- Respond to the original/seed question and all other questions directly addressed to them.

- Post at least four substantive contributions on each discussion thread.

- Offer evidence-based support (of own experience and/or cited research) at least once per thread.

- Demonstrate course knowledge and critical thinking.

- Apply normative/proper English and grammar (no texting or abbreviations).

|

Encourage learner attitude and expression style, respect and tolerance of all ideas, support de-personalized debates, explain the instructor role and commitments (facilitator, moderator, stimulator, teacher, etc.). Inform students that:

- The more/earlier participation, the better

- Last minute (Sunday), fly-by and tail-gating responses should be avoided.

- Instructors and students are expected reply within 24 hours to any direct question.

- Relaxed APA style should be employed (normative English and grammar, no online/short/icon, abbreviated language.)

|

Launch & manage the discussions during class |

Greet students on the first discussion week and facilitate introductions. |

Devote one question during the first week for all students to introduce themselves. Ask students to use the non-graded personal discussion thread for all non-course-related communications. Collect, consolidate and share a summary of all students in the class (picture, workplace, experience, management level, interests/ventures, etc.). As a 'cheat sheet', it will become handy during the course in asking students the specific/customized follow-up questions. |

Respond to all questions addressed to the instructor within 24 hours. |

Inform students on how to access the instructor in emergencies (i.e. when response is critically needed within hours). |

Draw lagging students in and inform Student Advisors of no-shows (missing a week of discussions). |

Look for and respond to 'Early Birds' and 'Late Comers'. Greet respondents on their first posting on a new question/week. All students should be on the discussions by EOD Wednesday. If a student is absent for a week, send him/her an email and inform the Student Advisor. Look for the early responses, praise them, leverage their postings to re-direct or deepen the discussion, invite others to respond. Email late responders (on Thursday) and encourage them to get involved earlier in the week. |

Acknowledge individuals with notable contributions and interrupt/stop unprofessional online behaviors. |

Be quick, personal and public in parsing student accomplishments. Discourage unwanted behaviors (not individuals) in public; use the private email channel to personally address individuals in extreme cases (i.e. disruptive behavior to the class, sub-par language skills, etc.). Don't wait till the end of the week just to grade the discussion; provide some interim clues on what you judge to be notable postings. Posting and emails (written communication in general) may cause misunderstandings and ill-feelings. Reach out to students and try to resolve behavior problems or sub-par performance issues in person or over the phone. |

- Manage the discussion quality to benefit all students - discourage superficial and irrelevant postings.

- Direct, facilitate, evolve and maintain the discussions to focus on stated weekly objectives (Limit serendipitous explorations to be contained within course objectives).

|

Discussions are not free flowing rambling. Manage (not in a micro/restrictive way) and facilitate the discussion. Enforce the overall direction/quality/depth of the discussion. Start with the original question/topic and maintain the discussion within the boundaries determined by the week's objectives. Always address your postings to all students, even when responding to a specific comment. Acknowledge students initiating question and invite the others to respond. If/when an unexpected opportunity arises to cover/discuss a very important business issue not necessarily/directly related to the week but still relevant to the course, open a new thread to follow-through and capture that topic. Add one question thread at mid-course and at the end to specifically solicit students' views on how the course is going for them, and solicit suggestions on improvement. Inform the faculty in charge of any better question emerging from the progressing discussions. |

Show substantive presence (facilitative, informative/teaching, and social) at least four days a week, including one week-end day. |

Read all new postings at least once a day and try to show a daily presence on discussions. Respond substantively to all questions addressed to the instructor, and comment on many other postings. Be opportunistic in leveraging students' postings to: confirm/rephrase views, request references/proofs, extend/direct the topic, stop digression/misunderstandings, prevent off-topic ranting, ask for relevant experiences, and motivate to think deeper, harder and differently. Provide a quick summary to students in each week's opening announcement, especially if there were particularly useful or insightful discussion postings. |

- Challenge students to think deeper, differently and critically.

- Share your own knowledge and experience, measurably (teach, don't control the discussion).

|

Treat own opinion as one among equals to encourage learning, argumentation and sharing. Stress the fact that there is always more than one possible approach and relevant example to most cases or issues. Indicate a 'right or wrong' answer in not sought, but rather advocate critical thinking and argumentation. Start contributing your own views, opinions and summaries late on the week, in order to avoid stifling the free-flowing discussion. |

Identify and manage (off-line) students with sub-par language skills. |

Don’t allow "texting" lingo and abbreviated language in discussions. Don't kick a 'language problem can' down the road…students are not helped in that manner. Consistently assess the language and communication skills of students, and provide an example of corrected language. |

Grade discussions by the third day of the following week. |

Use a continuous grading system and provide discussion grading on Monday. Summarize the main/problematic points on your weekly Announcement. Give individual students constructive feedback on discussions during the first couple of weeks. |

Report on important issues (no-shows, plagiarism, failed discussion topic, misconduct, etc.) |

Provide a “heads-up” to responsible faculty members regarding any performance and management issue that might require intervention that goes beyond the instructor's responsibility. |

Appendix B

Post University online MBA program profile

Program and discussion characteristics:

- Accelerated, eight week course program.

- Each week constitutes one unit within the course.

- Significant portion of student’s final grade (typically 30-40 percent) determined based on discussions.

- Discussions graded on critical thinking, evidence-based quality (supported by own research and/or professional experience), and engagement level over the week.

- Discussions facilitated and directed at all times.

Students and Instructors common characteristics:

- Professionals & practitioners.

- Have substantive work experience.

- Need to balance work/career, teaching/education and family life.

Typical weekly workload ranges for students and instructors:

- Course overall (including discussion): 16-18 hours.

- Discussions: 9-11 hours.