Implementing Learning-Oriented Assessment in an eTwinning

Online Course for Greek Teachers

|

Angelos Konstantinidis

Directorate of Secondary Education of Drama

Drama GREECE

akonstantinidis@sch.gr

Abstract

The Hellenic National Support Service for eTwinning provides short, intensive online courses for Greek teachers. (eTwinning is a flexible scheme that enables schools in Europe to work together on collaborative pedagogical projects using information and communication technologies.) This paper discusses the design and implementation of such a course to reflect a learning-oriented assessment (LOA) approach to teaching and learning. The aim of LOA is to strengthen the learning aspects of assessment, and it is premised on the ideas that assessment tasks should be designed as learning tasks, that students should be involved in the assessment process, and that feedback should be forward looking. Evaluation results attest to the effectiveness of the course in terms of its pedagogical design and implementation, and to the significance of the learning experience for participants. The results suggest that LOA is a promising pedagogical approach in online learning contexts for adult learners. The paper concludes with a discussion of the challenges in the implementation of LOA and the barriers to its wider acceptance, with suggestions made for future research.

Keywords: teacher professional development, e-learning, course design, assessment for learning, collaborative pedagogical school projects |

Introduction

Ensuring the quality of teaching and providing ongoing professional development for teachers constitute major challenges for the European Union and its member states (Council of the European Union, 2009). In response to the demands this presents, the Hellenic National Support Service (NSS) for eTwinning organized and ran six short, intensive online courses for Greek in-service teachers during 2010. These courses spanned a wide variety of topics – ranging from project management to Web 2.0 tools, and from teacher professional development to poverty and social exclusion – with the overarching goal being to promote the concepts and practices of eTwinning among Greek teachers.

This paper discusses the design, implementation, and evaluation of one of those courses that employed a learning-oriented assessment (LOA) strategy to teaching and learning. The rationale for adopting a LOA approach was based on the grounds that: (1) assessment should support learners in developing lifelong learning skills and attitudes (Boud, 2000); and (2) assessment tasks should promote appropriate learning since they have an influence on what learners will aim to achieve, as well as the amount of effort and time they will invest (Gibbs & Simpson, 2004-2005). The present study focuses on three questions:

- How can LOA be built into the design and delivery of a short, intensive online eTwinning course for teachers?

- How effective is the LOA approach in promoting learning, as measured in terms of participants' performance in the course?

- How do teachers perceive the experience of participating in an online eTwinning course that employs a LOA approach?

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: The next section introduces the eTwinning action as the context of the study. Next, the third section presents a description and analysis of the LOA framework. How the online course was designed and implemented is reported in the fourth section. The fifth section discusses the course assignments, explaining how they incorporate the elements of the LOA framework. An evaluation of the online course is presented in the sixth section. Finally, the concluding section provides a review and overall summary of the paper's content, along with an outline of the barriers encountered during the implementation of the course, before offering suggestions for future research.

The eTwinning Action

The eTwinning action is an initiative of the European Commission (EC) that "promotes school collaboration in Europe through the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) by providing support, tools and services to make it easy for schools to form short or long term partnerships in any subject area" (eTwinning Central Support Service [CSS], 2010, para. 1). In other words, it provides teachers across Europe with a flexible support infrastructure for implementing collaborative pedagogical school projects. Through eTwinning, teachers become "empowered to decide what to do and how to do it, with the sole requirements of exploiting ICT and collaborating with colleagues in another European country" (Crawley, Gilleran, Scimeca, Vuorikari, & Wastiau, 2009, p. 3).

The Central Support Service (CSS) for eTwinning is operated by European Schoolnet and headquartered in Brussels, Belgium. Additionally, there is a National Support Service (NSS) in each country (eTwinning CSS, 2010). Since its launch in 2005 as the main action of the EC's eLearning Programme, eTwinning has undergone tremendous growth. More than 13,000 schools were involved in eTwinning within the first year (Gilleran, 2006), and by 2008, over 50,000 teachers were registered for the initiative (Crawley et al., 2009). Six years after its launch, nearly 30,000 projects had been developed between two or more schools across Europe, with the total number of registered teachers being close to 130,000 and the number of participating schools exceeding 90,000 (eTwinning NSS desktop, 2011).

Learning-Oriented Assessment Framework

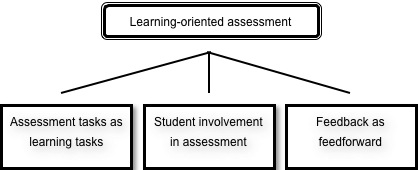

The term "learning-oriented assessment" (LOA) was coined by Carless, Joughin, and Mok (2006b) to refer to an approach to assessment that seeks to bring to the fore the aspects of assessment that encourage and support learning. The core concepts of LOA are illustrated in Figure 1, and they are each explained in greater detail below.

The key cornerstone of LOA is assessment task design, and its proponents emphasize the concept of "assessment tasks as learning tasks" (Carless, 2007, p. 59). In line with the principle of constructive alignment as advocated by Biggs (2003), in LOA it is stressed that "when assessment tasks embody the desired learning outcomes, students are primed for deep learning experiences by progressing towards these outcomes" (Carless, 2007, p. 59). A salient characteristic of LOA is the setting of germane assessment tasks – tasks that are very much related to authentic problems, that require transfer of learning from one context to another, and that call for students to apply knowledge and skills to demonstrate understanding (Knight, 2006). Promoting cooperation rather than competition, sustaining student effort and attention throughout the course, and allowing students some freedom of choice in assessment (Keppell & Carless, 2006) are secondary but nonetheless still important characteristics of assessment tasks in LOA.

Figure 1. The LOA framework

The second LOA concept, as illustrated in Figure 1, is student involvement in the assessment process (Carless, 2007). Central to this is the need for the process to be transparent to students. The importance of student involvement in and transparency of assessment is underpinned by the fact that students need to be aware of the learning goals and have access to clear and specific criteria in order to understand the purpose of the assessment and what is expected of them, as well as to be familiar with what constitutes good performance (Keppell & Carless, 2006). For this to be achieved, it is essential to engage students in activities that encourage critical reflection, peer feedback, and self-evaluation (Keppell & Carless, 2006). Typical examples of such activities include those that expose students to work samples or models/exemplars, those that involve them in identifying, drafting, or revising the criteria to be used in judging their performance, and those that require them to carry out peer assessment and peer editing tasks (see, for example, Cooper, 2000; Hendry, Bromberger, & Armstrong, 2011; Liu & Sadler 2003; Orsmond, Merry, & Reiling, 2002). It is especially important to note that although assessment is commonly seen as the practice of assigning marks or grades, in LOA the primary aim is to engage students in a process of refining and improving their own work as well as that of their peers; marks and grades are a peripheral part of the process (Carless et al., 2006a). Moreover, it is argued that placing the emphasis on marks during peer assessment can be detrimental to learning (Liu & Carless, 2006).

Lastly, as depicted in Figure 1, feedback is a vital component of LOA. However, simply providing feedback in of itself does not promote learning; several requisite conditions have to be met (Gibbs & Simpson, 2004-2005), and good feedback practices as identified in the literature (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006) need to be followed. Carless (2007) highlights the importance of supplying feedback that is timely (i.e., provided while it still matters to students), performance focused (i.e., focusing on evidence of learning instead of students' characteristics), and able to be used as feedforward (i.e., crafted and positioned with application to future tasks in mind). At this point it should be mentioned that LOA favors both the vertical (learners progressing through a hierarchy of cognitive skills and knowledge) and horizontal (what learners can do at any given level) dimensions of development (Knight, 2006). Although the value of feedback is acknowledged in LOA, even greater value is placed on feedforward as it leads to more effective horizontal transfer of learning (Knight, 2006). While feedback is typically provided by tutors, peers can also be a source of timely feedback (Carless et al., 2006a). In fact, peer feedback is highly regarded in LOA as it facilitates peer learning, stimulates reflection on standards achieved, and encourages self-regulated learning (Liu & Carless, 2006).

In short, the LOA framework involves three principles:

- Principle 1: Assessment tasks should be designed to stimulate sound learning practices amongst students.

- Principle 2: Assessment should involve students actively engaging with criteria, quality, their own and/or peers' performance.

- Principle 3: Feedback should be timely and forward-looking so as to support current and future student learning. (Carless, 2007, pp. 59-60)

There is much to be gained from adopting a holistic approach to LOA, rather than dealing with each of these three principles in isolation. For example, when assessment tasks are well aligned with the learning outcomes being targeted and when students are engaged in self and peer assessment, students are more likely to develop an understanding of the criteria and use feedback to improve their future performance. Ultimately, the real power of LOA lies in how it seamlessly guides and supports students in achieving the desired learning outcomes (Carless et al., 2006a).

Despite the fact that LOA seeks to accentuate and bring to the fore the learning features of assessment, it does not neglect its role in certification or credentialing. Instead, LOA seeks to reconcile those two functions of assessment, and to direct and target all forms of assessment toward "engineering appropriate student learning" (Carless, 2007, p. 59). Nevertheless, Knight (2006) warns that "if learning-oriented assessment is to be taken seriously, warranting needs to be subordinate to it" (p. 448).

Course Design and Implementation

Course Overview

The theme of the course was devoted to the 2010 European Year, the year for combatting poverty and social exclusion. The course was run over 10 days, from November 25 to December 3, 2010.

The course was designed to attract both primary and secondary school teachers who were keen to develop an eTwinning project relating to poverty and social exclusion. Based on this aim, the learning objectives of the course were to enable participants to: (1) demonstrate a critical understanding of poverty and social exclusion issues; and (2) assess the potential pedagogical and social benefits of developing an eTwinning project on poverty and social exclusion.

The course was announced on the Hellenic NSS website, and applications were invited from eTwinning members through the eTwinning newsletter. All Greek in-service teachers were eligible to apply, but the main target audience was those experienced in using ICT and developing eTwinning projects. Applications were received from 110 teachers, of whom 106 completed the registration procedure.

The course was delivered asynchronously, largely through the Moodle platform. A website and a private wiki were also set up, with the purpose of the former being to house the syllabus and the course material, and the purpose of the latter being to provide an additional opportunity for participants to upload drafts of their work and obtain peer feedback before submitting the final version. (The course website is accessible via the Hellenic NSS's main site at http://www.etwinning.gr/.) The course was organized into three sections. The first section aimed to raise participants' general awareness about poverty and social exclusion. A unique combination of up-to-date source material, video clips, and interactive exercises encouraged participants to think critically about and actively discuss poverty and social exclusion issues, vulnerable groups, and national policies/strategies for combatting the problem. The second section began with an overview of the eTwinning action, eTwinning projects, and the criteria used for evaluating eTwinning projects. Following this, exemplar lesson plans on poverty and social exclusion suitable for use in eTwinning projects were showcased to the participants, who were given the opportunity to analyze and critique the exemplars, considering how these could be used in their classes. The third and final section of the course aimed to stimulate and support participants in designing their own lessons on poverty and social exclusion that integrated ICT and involved collaboration over the Internet with another given school. In order to facilitate dialogue relevant to each participant's context, they were divided into four groups, each comprising 18-34 participants, according to their school type (primary school, secondary school, high school, or vocational/other school). Each participant designed a lesson plan that was subjected to critique and discussion by others in the group.

Profile of Participants

Most of the participants in the course (78 or 73%) were female. The participants had different levels of teaching experience, with the typical participant having taught for 11-20 years. The participants were working in a range of school types, and were teaching in a variety of subject areas. A large proportion of them were based in secondary schools (35 or 33%), primary schools (31 or 29%), or high schools (18 or 17%), and their predominant teaching subject areas were foreign literature (31 or 29%), primary school (22 or 21%), Greek literature (12 or 11%), and ICT (12 or 11%). More than half of the participants (55 or 52%) were newly registered in the eTwinning action, and almost three-quarters (77 or 73%) had yet to accomplish an eTwinning project. Nearly nine out of 10 of the applicants (94 or 89%) claimed to possess a "good" or "very good" level of ICT literacy.

Description of Course Assignments

There were three summative assessment tasks in the course, all of which resolved around the design of eTwinning activities: (1) critical review of activities (25% weighting); (2) activity planning (50% weighting); and (3) activity evaluation (25% weighting). The "critical review of activities" assignment was set during the second section of the course, and required participants to write a brief article (around 200 words) discussing the advantages and disadvantages of one or two of the sample activities, suggesting ways in which they could be improved or enhanced. The "activity planning" assignment was the centerpiece of the course, wherein participants needed to design an eTwinning activity relating to poverty and social exclusion, presenting their design in the form of a lesson plan. Participants were advised to reflect on the characteristics of their school (e.g., cooperation among staff, access to computer labs), their class (e.g., domain of the lesson, number of lessons per week), and their students (e.g., age, socioeconomic status, foreign language and ICT competence, Internet access from home) while tackling the task. This task was originally meant to be submitted by the end of the course, but in response to participants' requests to be given more time to work on the exercise, a three-day extension was granted. Lastly, the "activity evaluation" assignment entailed participants peer reviewing one another's lesson plans. To be allowed to partake in this optional task, students had to have submitted the previous assignment (activity planning) on time. Each participant was asked to provide anonymous feedback on the lesson plans produced by two other members of the cohort. Participants were informed that this task was neither mandatory nor would it affect the award of their course certification (since they had already successfully completed the two core assignments). They were urged, nonetheless, to join in to benefit from one another's insights and expertise.

In addition to the summative tasks, participants also undertook several formative assignments as they progressed through the course. Firstly, they were asked to post on the course discussion forum a brief personal introduction (including their name, hometown, teaching area, school, and something about themselves), along with a description of their perspective regarding the broad issue of poverty (e.g., what is poverty, who are considered to be poor people, etc.). They also had to comment on at least three other posts. Participants were free to choose the specific aspects of poverty to discuss in their posts, and were allowed flexibility in the presentation format (e.g., lyrics, photo, collage, etc.). Secondly, the course material on poverty and social exclusion contained an assortment of self-check quizzes and other forms of interactive content that played a formative assessment role. Thirdly, participants were asked to critically evaluate the sample activities on poverty and social exclusion, and to discuss their reactions and thoughts with their peers. Fourthly, they were asked to post a draft of the activity they had devised on their group forum, and to comment on at the draft activities of at least three of their peers. Participants also had the option of uploading their drafts to the course wiki to assist one another in refining their work.

Discussion of Course Assignments

This section discusses the rationale behind the course assignments and explains how the assessment practices in the course supported and reinforced learning in line with the principles of the LOA framework.

- Principle 1: Assessment tasks as learning tasks. First and foremost, the assessment tasks were well aligned with course aims and learning objectives. As stated earlier, the central aim of the course was to help teachers develop eTwinning projects on the topic of poverty and social exclusion. Short but structured formative exercises, each covering several concepts and issues, helped participants develop their understanding of the topic, while assessment tasks revolved around the design of eTwinning activities. By studying exemplars, novices learned the "whats" and "hows" of eTwinning activities, and they subsequently applied their newly acquired knowledge to demonstrate their understanding, with reference to their own teaching contexts. The assessment tasks were well sequenced to allow participants to build on previous learning, and were spread out evenly in an attempt to sustain participants' effort and attention throughout the course. A decision was made to avoid team-based assignments due to the short timeframe available, yet participants still had ample opportunities to assist one another with their work and contribute to the collective advancement of the cohort. Lastly, participants were afforded autonomy in terms of being able to choose which of the sample activities to review for the first assignment, in hope of promoting learning that was interesting and relevant to them personally.

- Principle 2: Student involvement in assessment. A major concern of the course was how to involve participants in the assessment process so that it would be more transparent to them. To this end, the "critical review of activities" assignment engaged participants in studying work samples or exemplars, the "activity evaluation" assignment encouraged them to undertake peer assessment, and the optional task of uploading their drafts to the course wiki sought to engage them in peer editing. The course tasks were designed to cultivate purposeful thinking and critical reflection, and they served as vehicles for participants to elaborate knowledge and insight into the nature of assessment. Finally, most of the formative assignments involved participants in a process of giving and receiving peer feedback that helped them develop a better understanding of the learning goals, and of what constitutes good performance.

- Principle 3: Feedback as feedforward. Peer and tutor feedback formed an integral part of the course. Above all, deliberate efforts were made to create an atmosphere conducive to constructive dialogue, self-esteem, and mutual respect. The main purpose of the formative assignments was to foster discussion around course concepts. In other words, participants were expected to give feedback to one another, while the tutor's role was to stimulate greater levels of interaction along the way. Participants therefore received regular, ample feedback from both their tutor and peers about their work and how it could be improved. Prior to final submission of their assignments, participants had the ability to act upon the feedback to address deficiencies in their performance. In addition, each participant was provided with in-depth, personalized feedback from the tutor following submission of the "critical review of activities" assignment. Careful attention was paid to the content and wording of the opening paragraph of the feedback message so as to assure participants that the feedback was an evaluation of their performance in context, not of themselves as individuals. Similarly, the closing statement of the message was written in a way that was motivating and encouraged dialogue around learning. Participants also had the opportunity to use the tutor's feedback on the "critical review of activities" assignment as feedforward, to improve their performance in the "activity planning" assignment. Last but not least, those who opted to participate in the "activity evaluation" assignment had yet another opportunity to receive even more peer feedback in preparation for their future practice, including the possible implementation of their lesson plans in their classes.

Evaluation of the Course

In this section, an evaluation of the effectiveness of the course is presented. Five sources were drawn upon to inform this evaluation, namely the three assignments completed by the participants, the online discussions, and feedback elicited through an online questionnaire. Additionally, issues relating to both the tutor's and participants' workload are discussed.

Assignments

The assignments helped the tutor to monitor participants' progress throughout the course and to gauge their understanding of the concepts that were covered. The tasks required higher-order thinking – that is, they called for participants to conceptualize, synthesize, and articulate their ideas. In the first assignment (critical review of activities), participants were required to analyze and evaluate exemplar lesson plans appropriate for implementation in eTwinning projects. Despite their efforts to tackle that task, approximately 60% of the participants failed to fully understand the importance of inter-school collaboration and ICT integration in eTwinning projects. For example, when providing suggestions on how to improve the exemplar lesson plans, they often failed to suggest ways of facilitating inter-school collaboration through the use of technology. However, this was not entirely surprising, since the majority of participants were newly registered in the eTwinning action and had not previously undertaken an eTwinning project. Nevertheless, the results in the second assignment (activity planning) point to substantial improvements in participants' knowledge and understanding. Practically all of the participants created lesson plans that integrated ICT and involved inter-school collaboration while focusing on the poverty and social exclusion issue. Finally, the high participation rate (65%) in the third, non-compulsory, assignment suggests that the course was effective in captivating participants' interest and engaging them in learning. The learning benefits arising from this assignment were twofold: participants were actively involved in commenting on the work of their peers as well as in considering their peers' comments about their own lesson plans. This process of peer and self-assessment necessitated deep engagement with the assessment criteria. Peer feedback provided through this assignment was constructive and encouraging; a content analysis revealed that 81% of the reviews identified strengths and 44% identified weaknesses of the lesson plans, with 63% of them containing suggestions for improvement.

Online Discussions

The online discussions provided a means for the tutor to continually appraise participants' engagement in the course, their understanding of the concepts, and their readiness to progress on to further content and tasks. According to statistics from the Moodle platform, participants who completed the course wrote, on average, 15 posts in the discussion forums. In the course evaluation questionnaire (covered in greater detail in the next subsection), participants, on average, self-reported each spending a total of nearly 12 hours taking part in the online discussions (including both reading others' posts and writing their own posts). This means a typical participant is likely to have written multiple posts and spent in excess of one hour per day in the discussion forums over the course's duration. Again, this is a testament to participants' interest and engagement in the course. Even more encouraging was the liveliness and thought-provoking nature of the discussions. As one participant commented:

I liked the discussions very much... I had the opportunity to exchange opinions with other people, with whom I was sharing an interest for the subject... Without necessarily agreeing with everyone, I was interested in "hearing" what was important for them and maybe also be "heard." I think that this is the most successful part of the course.

The discussions played a central role in developing participants' understanding of key eTwinning concepts. The tutor's efforts to establish a cordial and supportive atmosphere had a major, positive impact on the discussions as it served as a basis for mutual sharing of ideas and knowledge among participants. While all participants stood to gain knowledge and understanding, immersion in the discussions was especially beneficial for those who were new to eTwinning. For instance, one participant, an eTwinning novice, expressed the opinion that the greatest strength of the course was the discussions, which assisted her in acquiring fundamental knowledge regarding eTwinning:

Exchange of views through discussions gave me the opportunity to understand what exactly a[n eTwinning] project is and how I can design it and organize it.

Participants with some experience in eTwinning often stepped forward to serve as mentors for their novice peers, which gave rise to learning benefits for all involved. A participant who was experienced in eTwinning voiced her thoughts in this regard:

The greatest benefit for me was that the course organization taught me many things about my future engagement with eTwinning projects. I learned how a forum operates, what the common difficulties are that teachers encounter during design (e.g., common activities with partner school), the need for further education, e.g., on using tools, etc. I also realized that I "learned" a lot while I was explaining to other colleagues what we were doing in this course.

However, not all of the participants were equally positive about the discussions. A few felt overwhelmed by the number of messages, and did not feel they had enough time to fully elaborate on their thoughts and ideas. The following quotes are from two participants who described negative aspects of their experiences in the online discussions:

[The weakness of the online course was that there were] too many discussion groups. All were interesting but it was impossible to monitor all of them!

I think there must be a more specific discussion structure. Maybe, periodically, [there could be] a stimulus from the instructor with discussion about it. It was difficult for me to follow all comments, think about them, and give possible answers.

Course Evaluation Questionnaire

Participants' perceptions of the learning and assessment approach adopted for the course were formally evaluated using an online questionnaire. The course evaluation questionnaire consisted of 43 items in total, including Likert-type (with the options "strongly disagree," "disagree," "neither agree nor disagree," "agree," "strongly agree," and "don't know/not applicable"), rating-scale, and open-ended questions. Participants who exited the course prior to completion or who did not submit the assignments were also invited to fill out a short questionnaire aimed at ascertaining their reasons for dropping out. Selected items from the main questionnaire, namely those that map to the three principles of the LOA framework, are reported on below. English translations of both full questionnaires are included in Appendices A and B.

Both questionnaires were developed on the open-source LimeSurvey platform and hosted on the Hellenic NSS website. Participants were solicited via e-mail to complete the corresponding questionnaire, with fortnightly reminders sent to those who had not responded. All 72 of the participants who satisfied the course requirements filled out the questionnaire (i.e., 100% response rate), while 21 (out of 34) of the participants who had not met the expectations of the course filled out the "dropout" questionnaire. A further two participants who dropped out replied via email, yielding an overall response rate of 68% (23 out of 34) for the latter questionnaire. Dropouts chiefly named family/personal factors (87%) as reasons for withdrawal (other reasons included course workload, 35%; limited knowledge/skills in ICT, 17%; Internet connection problems, 13%; and reasons related to the particular course offering, 13%).

In general, participants who completed the course appreciated the individual aspects of the learning experience. In particular, on the design of the assessment tasks as learning tasks (Table 1), nearly all were of the view that: (1) completion of the assignments demanded deep, critical thinking rather than mere memorization (97%); (2) the assignments helped them better understand the subject matter of the course (96%); and (3) the assignments raised their interest in studying the course material (93%).

On the issue of participants' involvement in the assessment process (Table 2), the vast majority acknowledged that the discussions: (1) facilitated self-evaluation competence development (88%); and (2) helped them understand when an eTwinning activity might be successful (83%). In addition, 92% of those who took part in the optional "activity evaluation" assignment perceived it as facilitating self-evaluation competence development. One participant reflected on self and peer evaluation as follows:

I believe we should be less harsh with others than ourselves, but I think I could bear more critique, if I had a serious push for self-improvement through that. If someone is so engaged with my suggestion as to propose improvements, I should thank him.

With respect to feedback as feedforward (Table 3), close to all of the participants indicated that: (1) the tutor's comments were constructive (99%); and (2) the tutor's comments on their first submitted assignment helped them complete the second assignment (93%). Moreover, a majority of the participants agreed or strongly agreed that peer feedback on their suggestions in the online discussions facilitated their efforts to improve those suggestions (83%). Below are two extracts from participants' comments regarding the feedback they received from the tutor:

Instructor's comments for the first assignment were very constructive. Without discouraging me he managed to indicate my flaws and weaknesses.

The tutor was present as a catalyst in discussions. He was motivating us to ponder over our thoughts while he was providing the necessary directions.

Table 1. Participants' responses to items related to Principle 1 (assessment tasks as learning tasks)

Assessment Tasks as Learning Tasks

(N = 72) |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

Don't Know/Not applicable |

Completion of the assignments demanded deep, critical thinking rather than mere memorization |

0% |

0% |

2.8% |

27.8% |

69.4% |

0% |

The assignments helped me better understand the subject matter of the course |

0% |

0% |

4.2% |

51.4% |

44.4% |

0% |

The assignments raised my interest in studying the course material |

0% |

0% |

5.6% |

36.1% |

56.9% |

1.4% |

Table 2. Participants' responses to items related to Principle 2 (student involvement in assessment)

Students' Involvement in Assessment

(N = 72) |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

Don't Know/Not applicable |

The discussions helped me develop self-evaluation competence |

0% |

2.8% |

9.7% |

29.2% |

58.3% |

0% |

The discussions helped me understand when an eTwinning activity might be successful |

0% |

2.8% |

12.5% |

36.1% |

47.2% |

1.4% |

The second assignment (evaluation of two peer assignments) helped me develop self-evaluation competence (e.g., I can now more easily estimate whether the activity I plan will be successful or not)

(N = 47*) |

0% |

4.3% |

4.3% |

31.9% |

59.6% |

0% |

*This question was not asked of participants who did not take part in the third assignment.

Table 3. Participants' responses to items related to Principle 3 (feedback as feedforward)

Feedback as Feedforward

(N = 72) |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

Don't Know/Not applicable |

The tutor's comments (in discussions and personal e-mails) were constructive |

0% |

0% |

1.4% |

34.7% |

63.9% |

0% |

The tutor's comments on my first submitted assignment helped me complete the second assignment |

0% |

0% |

5.6% |

33.3% |

59.7% |

1.4% |

Other participants' comments on my suggestions facilitated my efforts to improve them |

0% |

1.4% |

12.5% |

47.2% |

36.1% |

1.4% |

On the whole, participants rated the course very favorably, but a few reservations were identified. More specifically, almost all of the participants rated the course as being of "high" or "very high" quality, and indicated that they derived "quite a lot" or "a great deal" of value from their participation in it. The majority of participants reported that they found the course to be "very organized" and "very interesting," and that they believed what they learned was likely to be of significant benefit to them in their future professional practice. Almost all of the participants specified that they would unhesitatingly recommend the course to other teachers. The small number of reservations identified were related to the overwhelming number of contributions (posts and comments) in the discussion forums generated by the large number of participants, the absence of face-to-face meetings, and the short timeframe of the course, which made it highly intensive.

Course Workload

When designing the course, an attempt was made to keep the workload manageable for both the participants and the tutor. The participants reported that they spent, on average, 16-20 hours studying the course material, taking part in discussions, and working on assignments throughout the period of the course, and most of them perceived the workload of the course as manageable. However, nearly 40% of the participants felt that the workload was significant, and as mentioned earlier, 35% of the respondents to the "dropout" questionnaire cited course workload as one of the main reasons for quitting. Moreover, approximately 20% of the participants expressed reservations regarding the short timeframe, and several complained about the intensiveness of the course and the difficulties this caused due to their concurrent professional obligations. In light of this feedback, it is believed that the duration of the course could be increased to around 12-15 days (keeping the total workload the same) without compromising its quality.

The tutor's workload was high, partly because of the large number of participants coupled with the short course duration. Much time and effort were necessary to devise the learning outcomes, activities, and assignments, as well as to develop the materials for the course, in advance of the course's commencement. Additionally, a large time investment was made on the part of the tutor throughout the course – but especially in the early stages – to ensure participants' queries were responded to promptly. As online courses tend to be labor intensive for instructors, sound organizational and time-management strategies are vital (Shi, Bonk, & Magjuka, 2006). The appointment of auxiliary or assistant tutors could be beneficial in future offerings of the course as this would lighten the main tutor's workload, while also allowing the participants to receive more feedback from yet another perspective (see Salmon, 2002).

Conclusion

To accommodate a growing need for teacher professional development and in-service training, the Hellenic NSS for eTwinning provides short online courses for Greek teachers. In this paper, the potential of LOA was explored and investigated through an examination of its application in one of these courses. The design of the course was based on the three principles of the LOA framework. Firstly, the assessment tasks were designed as learning tasks in the form of assignments aligning with the learning outcomes of the course and requiring learners to synthesize knowledge acquired through the course readings, exercises, and discussions. Secondly, participants were actively involved in the assessment process through opportunities to collaborate and exchange formative feedback with one another, as well as to engage in peer evaluation of assignments. Thirdly, the provision of forward-looking feedback was a key feature of the teaching and learning approach adopted in the course, with both peer and tutor-supplied feedback given to participants that was also timely and constructive in terms of its potential for improving their performance and informing their future practice.

The results indicate that the course was effective, and that the learning experience was significant for participants. While this study was conducted in a specific context – namely an online professional development course on eTwinning for Greek teachers – and its generalizability is limited, the results nonetheless suggest that LOA is a promising pedagogical approach that can provide a sound framework for use in the design of online courses for adult learners. Additionally, and equally important, this study adds to the scarce body of empirical research on online professional development courses for teachers on eTwinning. The findings and lessons learned will be valuable to those responsible for developing and/or delivering such courses.

Notwithstanding the success of the course and the achievement of its objectives, there are important challenges facing the use and acceptance of LOA more broadly. LOA can be combined with other approaches to and models of online course design, but special attention must be paid to the planning of the overall assessment strategy and to the development of the individual assessment tasks in the course. The overall strategy should be planned in such a way so as to encompass all three principles of LOA, and the individual tasks should be systematically designed to support and embody them. Moreover, in order for peer feedback to work effectively, the learning environment must be supportive and the feedback needs to be delivered in a non-threatening manner. Learners must feel comfortable in the learning environment in order to build a relationship of trust with one another, which, in turn, will enable them to exchange honest and constructive feedback. Lastly, as noted earlier, for successful deployment of LOA to occur, marks, grades, and certification should be seen as secondary to learning. As such, LOA alone is not suitable for making critical, high-stakes decisions about learners, and must be supplemented by or employed in conjunction with other approaches when conducting assessment for the purpose of awarding formal qualifications. In the case of the course discussed in this paper, the certificates of participation issued by the Hellenic NSS have minimal or even no direct impact on the participants' career progression (in terms of salary, promotion, etc.), or on their ability to gain entry into academic courses of study. It was thus an appropriate setting in which to trial the application of LOA in online courses. Future studies might more closely examine specific aspects of LOA and its potential, striving to advance our understanding of how to design effective online courses based on the LOA approach and of how to reconcile LOA with existing instructional approaches. It would be also interesting for future research to test the effectiveness of LOA in other countries and cultures, as well as to explore its use in different courses and disciplines.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to sincerely thank James Lamb, Research Associate, MSc in E-learning, The University of Edinburgh, for his helpful ideas and comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

References

Biggs, J. (2003). Aligning teaching for constructing learning. Retrieved from http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/York/documents/resources/resourcedatabase/id477_aligning_teaching_for_constructing_learning.pdf

Boud, D. (2000). Sustainable assessment: Rethinking assessment for the learning society. Studies in Continuing Education, 22(2), 151-167. doi:10.1080/713695728

Carless, D. (2007). Learning-oriented assessment: Conceptual bases and practical implications. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(1), 57-66. doi:10.1080/14703290601081332

Carless, D., Joughin, G., Liu, N.-F., & Associates (2006a). How assessment supports learning: Learning-oriented assessment in action. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Carless, D., Joughin, G., & Mok, M. M. C. (2006b). Learning-oriented assessment: Principles and practice. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(4), 395-398. doi:10.1080/02602930600679043

Cooper, N. J. (2000). Facilitating learning from formative feedback in Level 3 assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 25(3), 279-291. doi:10.1080/713611435

Council of the European Union. (2009). Council conclusions of 12 May 2009 on a strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training ('ET 2020'). Official Journal of the European Union, 52(C 119), 2-10. doi:10.3000/17252423.C_2009.119.eng

Crawley, C., Gilleran, A., Scimeca, S., Vuorikari, R., & Wastiau, P. (2009). Beyond school projects: A report on eTwinning 2008-2009. Brussels, Belgium: Central Support Service for eTwinning, European Schoolnet. Retrieved from http://resources.eun.org/etwinning/25/EN_eTwinning_165x230_Report.pdf

eTwinning Central Support Service. (2010). Overview of eTwinning. Retrieved from http://www.etwinning.net/en/pub/news/press_corner/overview_of_etwinning.htm

eTwinning NSS desktop. (2011). Statistics. Retrieved from http://nss.etwinning.net/

Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2004-2005). Conditions under which assessment supports students' learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1, 3-31. http://www2.glos.ac.uk/offload/tli/lets/lathe/issue1/articles/simpson.pdf

Gilleran, A. (2006). Introduction. In A. Gilleran (Ed.), Learning with eTwinning (pp. 2-3). Brussels, Belgium: Central Support Service for eTwinning, European Schoolnet. Retrieved from http://www.etwinning.net/shared/data/etwinning/booklet/booklet_final_en.pdf

Hendry, G. D., Bromberger, N., & Armstrong, S. (2011). Constructive guidance and feedback for learning: The usefulness of exemplars, marking sheets and different types of feedback in a first year law subject. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(1), 1-11. doi:10.1080/02602930903128904

Keppell, M., & Carless, D. (2006). Learning-oriented assessment: A technology-based case study. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 13(2), 179-191. doi:10.1080/09695940600703944

Knight, P. (2006). The local practices of assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(4), 435-452. doi:10.1080/02602930600679126

Liu, J., & Sadler, R. W. (2003). The effect and affect of peer review in electronic versus traditional modes on L2 writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 2(3), 193-227. doi:10.1016/S1475-1585(03)00025-0

Liu, N. F., & Carless, D. (2006). Peer feedback: The learning element of peer assessment. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(3), 279-290. doi:10.1080/13562510600680582

Nicol, D., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218. doi:10.1080/03075070600572090

Orsmond, P., Merry, S., & Reiling, K. (2002). The use of exemplars and formative feedback when using student derived marking criteria in peer and self-assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 27(4), 309-323. doi:10.1080/0260293022000001337

Salmon, G. (2002). E-tivities: The key to active online learning. London, UK: Kogan Page.

Shi, M., Bonk, C. J., & Magjuka, R. J. (2006). Time management strategies for online teaching. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 3(2), 3-8. Retrieved from http://www.itdl.org/journal/feb_06/article01.htm

Appendix A: Course Evaluation Questionnaire (Translated from Greek)

Personal Details

1. At what level would you rate yourself with regard to your proficiency in the use of new technologies? (Choose one of the following answers)

- Elementary (e.g., I know how to use basic Internet applications)

- Basic (e.g., I use a word processing program quite often and I have an e-mail account)

- Moderate (e.g., I occasionally/sometimes use one or two advanced applications like Excel, Photoshop, blog, etc.)

- Good (e.g., I often use one or two advanced applications like Excel, Photoshop, blog, etc.)

- Very good (e.g., I use several advanced applications)

2. How many eTwinning projects have you carried through (to October 30, 2010)? (Choose one of the following answers)

- None

- 1-2

- 3-6

- 7-10

- More than 10

Evaluation of Course Material

3. Indicate your agreement (or otherwise) with the following statements: (Rank all statements)

|

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

Don't Know/Not applicable |

The lesson goals were clear |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The course material contributed to a better understanding of the subject |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interaction with information (e.g., through multiple-choice questions) made the course material easier to understand |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The use of videos made the course material easier to understand |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Do you have any further comments to make regarding the course material? (Optional)

Evaluation of Assignments

5. Indicate your agreement (or otherwise) with the following statements: (Rank all statements)

|

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

Don't Know/Not applicable |

The assignments helped me better understand the subject matter of the course |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Completion of the assignments demanded deep, critical thinking rather than mere memorization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The assignments raised my interest in studying the course material |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The assignments raised my interest in attending/contributing to course discussions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The tutor's comments on my first submitted assignment helped me complete the second assignment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The second assignment (evaluation of two peer assignments) helped me develop self-evaluation competence (e.g., I can now more easily estimate whether the activity I plan will be successful or not) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The tutor's comments on my submitted assignments were motivating to my participation in the course |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Do you have any further comments to make regarding the course assignments? (Optional)

Evaluation of Discussions

7. Indicate your agreement (or otherwise) with the following statements: (Rank all statements)

|

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

Don't Know/Not applicable |

The discussions were interesting and motivated me to participate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other participants' comments on my suggestions facilitated my efforts to improve them |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The discussions raised my interest in studying the course material |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The discussions helped me develop self-evaluation competence (e.g., while reading peer suggestions I was attempting to pinpoint positives and negatives) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The discussions helped me understand when an eTwinning activity might be successful |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8. How much time (in hours) did you spend taking part in course discussions (reading and writing comments)?

9. How many comments did you write (approximately)?

10. Do you have any further comments to make regarding the course discussions? (Optional)

Evaluation of Tutor

11. Indicate your agreement (or otherwise) with the following statements: (Rank all statements)

|

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

Don't Know/Not applicable |

The tutor offered guidance regarding the course activities/assignments |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The tutor encouraged me to engage in discussion with him about the course |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The tutor encouraged me to engage in discussions with other participants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The tutor's comments (in discussions and personal e-mails) were constructive |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I am satisfied with the support I received from the tutor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

12. Do you have any further comments to make regarding the tutor? (Optional)

Overall Course Evaluation

13. Overall, I found the quality of this course to be: (Choose one of the following answers)

- Extremely poor

- Poor

- Average

- High

- Very high

14. Overall, I found the course to be: (Choose one of the following answers)

- Of no interest

- Of little interest

- Quite interesting

- Very interesting

- Extremely interesting

15. Overall, I found the course to be: (Choose one of the following answers)

- Not at all organized

- A little organized

- Quite organized

- Very organized

- Extremely organized

16. By participating in this course what I learned was: (Choose one of the following answers)

- Of no value

- Of little value

- Somewhat of value

- Quite a lot of value

- A great deal of value

17. In terms of my future professional practice the course is likely to be: (Choose one of the following answers)

- Of no value

- Of little value

- Of some value

- Of significant value

- Of very high value

18a. If the course were to be repeated, I would recommend it to other teachers: (Choose one of the following answers)

- Not at all

- With a significant number of reservations

- With reservation

- With only a few reservations

- Unreservedly

18b. If you had reservations you would share, what would they be? (Optional)

19. Overall, how much time (in hours) did you spend on the course (studying the material, participating in discussions, and completing assignments)?

20. Overall, I found the workload in this course (studying the material, participating in discussions, and completing assignments) to be: (Choose one of the following answers)

- Very easy to maintain

- Relatively easy to maintain

- Manageable

- Significant

- High

21. By the end of the course: (Choose one of the following answers)

- I have a strongly negative inclination toward the eTwinning action and eTwinning projects

- I have a negative inclination toward the eTwinning action and eTwinning projects

- I have a neutral opinion toward the eTwinning action and eTwinning projects

- I have a positive inclination toward the eTwinning action and eTwinning projects

- I have a strongly positive inclination toward the eTwinning action and eTwinning projects

22a. With which of the following statements do you most strongly agree in terms of initiating an eTwinning project regarding poverty and social exclusion? (Choose one of the following answers)

- I am unable to start a project regarding poverty and social exclusion

- I am not interested in starting a project regarding poverty and social exclusion

- I had already started a project regarding poverty and social exclusion (prior to my participation in the course)

- I may start a project regarding poverty and social exclusion in the future

- I will start a project regarding poverty and social exclusion as soon as possible

22b. For what reason(s) do you feel you are unable to start a project regarding poverty and social exclusion? (Optional)

22c. For what reason(s) are you are not interested in starting a project regarding poverty and social exclusion? (Optional)

23. What was the greatest strength of this course? (Optional)

24. What was the greatest weakness of this course? (Optional)

Appendix B: Dropout Questionnaire (Translated from Greek)

1. At what level would you rate yourself with regard to your proficiency in the use of new technologies? (Choose one of the following answers)

- Elementary (e.g., I know how to use basic Internet applications)

- Basic (e.g., I use a word processing program quite often and I have an e-mail account)

- Moderate (e.g., I occasionally/sometimes use one or two advanced applications like Excel, Photoshop, blog, etc.)

- Good (e.g., I often use one or two advanced applications like Excel, Photoshop, blog, etc.)

- Very good (e.g., I use several advanced applications)

2. How many eTwinning projects have you carried through (to October 31, 2010)? (Choose one of the following answers)

- None

- 1-2

- 3-6

- 7-10

- More than 10

3. I found the topic of the course (poverty and social exclusion) to be: (Choose one of the following answers)

- Of no interest

- Of little interest

- Of some interest

- Very interesting

- Extremely interesting

4. Indicate your agreement (or otherwise) with the following statements: (Rank all statements)

|

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

Don't Know/Not applicable |

My limited technological knowledge/skills hindered my participation in the course |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Family/personal factors (e.g., lack of time) hindered my participation in the course |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I could not cope with the workload of the course (it was unmanageable) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I encountered Internet connection problems that hindered my participation in the course |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The particular course offering was of no interest to me |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I did not receive the necessary support from the tutor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Please provide any other comments you might wish to add regarding your participation in the course. (Optional)