| MERLOT

Journal of Online Learning and Teaching |

Vol. 2,

No. 4, December 2006

|

|

Beyond the Printed Page: Style Suggestions for Electronic

Texts

Gary L.

Bradshaw

Professor of Psychology

Mississippi State University

Mississippi State, MS

USA

glb2@psychology.msstate.edu

Robert J.

Crutcher

Assistant Professor

of Psychology

University of Dayton

Dayton, OH

USA

robert.crutcher@notes.udayton.edu

Abstract

When compared

to their traditional print-based counterparts, electronic texts

often fall far short of the mark in readability, portability,

rapid access to information, and the ability to personalize a

printed text by highlighting and jotting down notes in the

margin. Given these advantages, readers typically exhibit a

strong preference for a print-based text instead of its

electronic counterpart. The authors propose that these

deficiencies derive from an inappropriate model of an electronic

text, utilize psychological principles to suggest how to improve

electronic texts that are difficult or impossible to reproduce

in print media, and describe student reactions to an electronic

text,

ePsych, that employs these principles. A survey revealed

that students in a variety of classes reacted positively to

ePsych and rated it better than traditional print-based texts.

Keywords:

Instructional Technology, Multimedia,

Learning Objects, Texts, Learning and Technology

Introduction

Imagine you

have the opportunity to visit a newly discovered civilization on

Earth. This civilization, whose technology is both primitive

and surprisingly sophisticated, has been cut off from the rest

of the world for centuries. You visit this strange and different

land, learn something of the language, and immerse yourself in

this new and fascinating culture. One night you are invited to

an entertainment event that has all of the locals excited. You

gather, from your limited understanding of the language, that

moving images will be shown representing a story. “Ah! A

movie!” you think to yourself. “This will be a real treat!”

Your host

accompanies you to the building, which indeed resembles a crude

movie theater. Then the lights go down and the audience falls

quiet. But instead of a familiar movie, words appear projected

on the screen with an occasional accompanying sketch. You can

barely read the language and so it is difficult to follow the

story. Looking around you notice that some members of the

audience are quickly scanning the words, while others read more

slowly. As the projection fades out, the audience bursts into

applause. “Must have been a good script,” you think to

yourself. “I wish I could have understood more.”

This scenario

highlights an important principle: to effectively communicate or

instruct requires exploiting the unique capabilities of a

specific medium. Using a movie projector to display words on a

screen fails to exploit the capabilities of motion pictures to

their fullest extent. Hollywood creates realistic movies that

employ sound and moving images to create a vivid experience for

the audience. The best examples of the film medium (e.g.

Hitchcock's Rear Window) would lose all of their

storytelling power if translated to a textual re-telling of the

story.

A screenplay

on the silver screen may seem an absurd idea, but many

electronic texts are only a small improvement over this

solution. Consider a publisher who creates a .pdf file of a

textbook and sells it on a CD-ROM. Students may open the .pdf

file to read the text and discover that they cannot even read an

entire page on their screen; instead, they must scroll down to

read the first column, then scroll back upwards to read the

second, then scroll past a meaningless page break to view the

next page, and so on. A table of contents may be provided, and

perhaps the file has some embedded hyperlinks that move the

student to a new section of the document without any obvious way

to go back. But again, the authors question whether this is a

reasonable utilization of such a powerful communication

technology.

In study

after study, electronic texts fall short of their printed

counterparts. Dillon (2004) comprehensively reviewed the

literature on electronic versus printed texts, and documented

numerous shortcomings of electronic texts. Problems begin with

the difference between a computer screen and a piece of paper:

paper has higher resolution and can convey more information than

a screen can. Books do not have to download and render pages;

one can rapidly ‘flip through’ a book to find material of

interest, while computers are slower to access and present

material. Books are also highly portable and self-contained:

they do not need a network connection or electrical power.

Finally, books are personalizable:

readers can highlight interesting material, jot notes down in

the margins, and so on.

These

advantages have traditionally proven unbeatable when printed

texts are compared to their electronic counterparts: Users

prefer books to electronic texts. For this reason, faculty

assign books that cost 4 times what a CD-ROM does, even though

students are motivated to cut costs whenever possible.

A central

thesis of this report is that the deficiencies of electronic

texts are not intrinsic, but are the result of

misadapting printed text to a

computer environment by not exploiting or exploring the unique

capabilities of a computer medium in handling text. Like the

screenplay on the silver screen, the approach simply transplants

the old medium into the new.

Imagining

what electronic texts might be, rather than what they currently

are, suggests that a mature electronic text will differ far more

radically from its printed text counterpart than a movie differs

from a novel. Electronic texts could, of course, include

full-screen video: computers can do a fine job of showing the

latest DVD. But computers have capabilities that movies lack.

A computer can interact with the user as well as simulate a

process or model of almost any imaginable sort. In short, an

electronic .pdf version of a printed text is no more acceptable

than is a screenplay on the silver screen.

Economic

considerations also favor electronic texts over printed ones,

provided readers will accept them. The economic claim is simple:

paper costs more than electrons. Textbooks are expensive and

are getting more so: a recent study found that college textbook

prices were rising four times faster than the rate of inflation

(Rube, 2005). Although this number has been disputed by

textbook publishers, there is little doubt that college texts

are expensive and getting more so. Sixty percent of a college

textbook price goes to publication costs; another 17% pays for

bookstore operations, while the author, publisher, and bookstore

share the remaining 23% as royalties and profit. As books

become lengthier, use higher grades of paper and make more

extensive use of 4-color graphics, the production costs will

continue to rise. New editions are being released at a faster

pace and now average 3.8 years (Pressler, 2004), so books have

to be replaced frequently, adding to the price.

It is

important to recognize that each new edition of a textbook must

be completely republished, no matter how much (or little) has

changed. It is not possible to simply rip out and replace only

the pages that require revising – instead the old versions are

obsolete and remaining copies are typically destroyed by the

publisher when the new edition appears.

Electronic

textbooks have a very different set of driving economics. The

cost of delivering 4-color graphics is little different from a

simple black-and-white text. Reproducing a text can be done on

demand by a simple activity like visiting a page on a website.

Distribution costs are minimal. Revised editions cost far less

to produce than a new edition, as changes can be made

incrementally by updating instead of replacing the text. For an

existing print-based textbook that costs $100 nearly all of the

$77 in production and distribution costs could be eliminated in

an electronic text that would cost students only $23 to $25.

These costs could be further reduced by a subscription-based

model that did not allow textbooks to be resold to other

students, increasing the number of units sold by the publisher.

Style

considerations for Electronic Texts

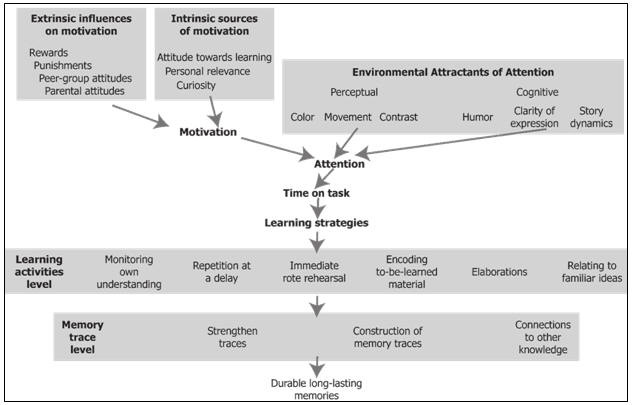

Bradshaw

(2005) discussed three factors that help improve student mastery

of material: Concreteness, connectedness, and practice. These

factors all improve the memorability of text. But other

higher-level factors, both internal and external, also have

strong influences on learning. Figure 1 presents a partial and

incomplete view of some of these factors. Motivation and

attention appear at the top of the figure. Motivation might be

considered the fuel for learning, while attention is the engine

that drives learning. Given sufficient motivation and attention,

students will spend time on the task of learning, a crucial

factor in any account of human learning (Simon, 2001). However,

the benefit of that time depends critically on the specific

learning activities and strategies students use. Students may

spend their time ineffectively by repeating the material, or

they may spend their time more effectively by constructing

elaborations, relating the material to familiar ideas, etc.

Motivation

comes from extrinsic influences (rewards, punishments,

peer-group pressure, parental attitudes) and from intrinsic

sources (curiosity, the personal relevance the information may

have, etc.) Considerable evidence suggests that extrinsic

rewards can undermine intrinsic motivation in educational

settings (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999).

ePsych: an

Electronic Text Introducing Psychology

Like the

traditional introductory psychology textbook,

ePsych's goal is to introduce students to the field of

psychology. However, ePsych incorporates several features to

improve student motivation, attention, and memory for the

material. Perhaps the most obvious are the inclusion of

programs (java applets) that allow students to conduct

experiments or to simulate cognitive models and video clip

demonstrations. But ePsych also has many other more subtle

differences from existing printed texts. First, ePsych does not

follow a traditional “textbook” style of presentation: Given the

long association students have with traditional textbooks and

schoolwork, they are likely to treat any textbook-like coverage

as “yet another chore to accomplish.” Instead ePsych uses a

journey metaphor in which students visit exotic planets, meet

interesting characters, and participate in various adventures.

In one module,

Seth Smidlap is captured by aliens, and then realizes he is

colorblind when he can’t tell a ripe red fruit from an

unripe-but-poisonous green fruit. In another module,

Professor Mindstein shrinks his class down to microscopic size

to inspect neurons and synapses. Students respond

positively to this style. Students have remarked on multiple

occasions “I wanted to look at more material on the site.”

Washburn

(2003) noted “game-like conditions promoted efficient and

effective training of these undergraduate students, an effect

that has been replicated with nonhuman primates, with college

students learning classroom-relevant information, and with

adults from a temporary employment agency” (p. 190). Our

material shares many of the game-like aspects that Washburn

identifies: “movement, interactivity, competition, scorekeeping,

and graphics” (p. 190). Curiously, similar considerations have

discouraged us from incorporating graded quizzes into the site.

Although quizzes would allow for scorekeeping, they would also

provide an external motivation for performing the task that

would likely undermine the students’ internal motivation. Our

“skill exent face="Arial" size="2">Figure

1 shows that attention is partly a function of motivation, but

it cions are

more advantageous for overall retention of the subject matter if

the concepts or rules taught contain a temporal course or

progression, movement, or spatial relations” (p. 255).

Betrancourt and Tversky (2000) concluded “animation is likely to

be useful when the learning material entails motion, trajectory,

or change over time, so that the animation helps to build a

mental model of the dynamics” (p. 326). ePsych incorporates

animated graphs (one

illustrates the change in membrane potential over time as a

neuron fires), animated videos (one

illustrates an unmyelinated neuron “racing against” a myelinated

one), and java applets (our

model of Pandemonium includes real screaming demons!). At a

more cognitive level, ePsych's modules often include jokes and

employ conventional story elements (plot, challenge to the

protagonist, resolution, etc.) that can engage a readers’

attention.

Figure 1. Paths to

Knowledge (An Incomplete View)

Another line

of research from the education community indicates that material

is better understood and remembered if an embodied agent

instead of an all-but-invisible author communicates it (Moreno,

Mayer, & Lester, 2000). This is another reason why ePsych uses

characters and story lines in its presentation. Finally,

ePsych's principal characters (guides) are young, dedicated, and

successful scientists of different races and both sexes who

portray scientists in a positive light and can serve as role

models for students.

Other

Style Considerations: Web versus Text

There are a

few other issues that impact student learning, although somewhat

indirectly. Many of these issues stem from some significant

differences between computer-based publication and traditional

textbook publication.

Publishers

are concerned with two different costs: the cost of producing

the first copy of a textbook and the cost of reproducing that

copy. Production costs include payments to authors, editors,

artists, and typesetters. The cost of reproduction depends on

the length of the book and the number of colors of ink on each

page. Introductory Psychology texts incorporate numerous

photographs and graphics on most pages. More advanced textbooks

use little or no color printing and have a much higher ratio of

text to image. Even introductory texts have a fairly high ratio

of text to image: It is rare for a textbook to have multiple

images to illustrate a topic. This style is dictated by the

expense of paper, four-color printers, etc.

In

computer-based publication, the economics of reproduction are

quite different. A CD-ROM, for example, can hold 600 Mbytes of

information as easily as it holds one. This allows authors to

shift to a different style of presentation that incorporates

considerably more pictorial material. Computer publication via

the web has similar economics: The cost of reproduction,

especially of color images, is small and inconsequential,

permitting a graphically intensive publishing style that is

all-but-forbidden in textbook publishing.

Several

ePsych modules incorporate this style. One of the best

illustrations of this style occurs in ePsych's

module on the neuron. This module incorporates several

graphs (some of which are animated) to explain the neuron.

Our basic illustration of the neuron itself appears five

different times with only two labels per illustration. In

contrast, a textbook would present one illustration with 10

labels. Students reading the text need to perform a more

difficult search over 10 labels to find the part that is

identified, but with ePsych this search is all but avoided. As

ePsych's modules have been refined, new ways have been

discovered to incorporate a rich blend of textual and pictorial

material, interactive models and demonstrations, and key

experiments to complete the modules. Adapting material from a

book style (books and journal articles are the primary sources

of material for the site) to this new computer-publication style

is a significant challenge, but one that should ultimately prove

to be worth the effort.

Student

Reactions to ePsych

In order to

determine how successful ePsych is at communicating information

to students, a student satisfaction survey was conducted in

several courses on different campuses. Students were assigned

to read one or more modules on ePsych as a part of their regular

class assignments. Then these students were given an evaluation

survey that asked several questions about their reaction to the

material they read. Several questions asked students to compare

ePsych with a traditional printed text. These include items

such as: (Q6) “Compared to a textbook, how easy or difficult was

it to comprehend the ideas that were presented?”; (Q9) “Which is

more convenient and easy to use? A textbook or ePsych?”; and

(Q10) “If you had to choose between a traditional textbook and

the ePsych module, which do you think you would prefer?” Other

questions asked about student reactions to different features of

ePsych, including questions like (Q8) “How did you react to the

characters who were present in the module?”

Most

of the students participating in the survey were from

introductory psychology classes (183 students in 4 different

classes at three different colleges/universities), but 47

students in 2 advanced classes (Cognitive Psychology and

Physiological Psychology) were included as well. Survey

questions were based on a 5-point Likert scale, and

participation in the survey was voluntary and did not affect

student’s class grades. (In addition to the 10 Likert-scale

questions, the survey included an additional 9 background

questions that will not be discussed here.)

A total of

252 surveys were received (students in some classes completed

multiple surveys). On all 10 questions the students average

responses were positive toward ePsych. Independent t-tests were

conducted on each question to determine whether the average

responses differed from the neutral point on the scale, and all

10 questions led to significant results (p < .001). The item

that was closest to the neutral point (3.0) was Question 10: “If

you had to choose between a traditional textbook and the ePsych

module, which do you think you would prefer?” The average score

for that question was 3.35, slightly favoring ePsych over a

textbook. Yet it is significant that this result favors ePsych,

while other evaluations of electronic texts usually show a

strong preference for a printed text (Dillon, 2004).

Eight items

on the survey (excluding Q9 and Q10) were subjected to a factor

analysis. The factor analysis resulted in two factors. One

factor included only two items, but both measured the interface

to ePsych: (Q2) “How fast or slow was it to access the material

on the site?”; and (Q7) “How easy or difficult was it to

maneuver around the module and access material?” The other

factor included questions about how students reacted to

characters or the story line, how easy the material was to

understand, and so on. The two factor scores were then used in

a linear regression to predict the preference for

textbook/ePsych on Question 10. Both factors were significant

predictors, and the model predicted preferences significantly (r2

= 0.328; p < 0.001).

A third

regression was performed to predict responses to the question

(Q1) “What was your reaction to the ePsych module and the

concepts it contained?” Predicting questions included an item

about their reaction to the story setting, their reaction to

humor in ePsych, and their reaction to the characters in the

modules. All three factors were entered in a stepwise

regression analysis, with character appreciation being the first

item entered, the reaction to humor second, and their

appreciation of the story line entered third. The

three-variable model predicted enjoyment significantly (r2

=0.258; p < 0.001).

Discussion

An extensive

survey, conducted in 6 different classes on four different

campuses, demonstrated that ePsych is an effective

electronic-text alternative to a traditional printed text.

Although 44 surveys indicated a strong preference for a

traditional textbook, nearly twice that number, 75, indicated a

strong preference for ePsych. The primary reason for preferring

a traditional textbook was its universal availability, while the

primary reasons for preferring ePsych were its fun style and

careful, easy-to-read explanations. ePsych thus demonstrates

that it is possible to overcome many of the intrinsic problems

with electronic texts by adopting a style of presentation that

exploits the strengths of electronic texts: their ability to

present multimedia elements, the low cost of including colorful

images, and adopting a style of presentation that incorporates

story lines and humor to help capture and retain student

attention.

Acknowledgements

Ben Stephens,

Lynn Della-Pietra, and Sara DeHart-Young involved their classes

in ePsych and provided student survey data; their efforts are

very much appreciated. Kirk Gatlin entered data for us. Many

individuals have contributed to the development of ePsych over

the past several years. Prof. Mike Thorne has scripted several

ePsych modules in the recent past. Chris Nolen produced much of

the ePsych artwork, with Clayton Graff and Zach Prichard

contributing much of the 3-D work. Connie Harris brought many

of the elements together with her HTML work. Don Goodman wrote

several of the simulations and java demonstrations. Prof. Nancy

McCarley assisted in internal evaluations of ePsych. Additional

contributors include Bernard Steinman, Jennifer Daniels, and

Tony Hocevar. ePsych is richer for all the fine work performed

by these great people! This material is based on work supported

by the National Science Foundation under grants DUE-9981004 and

DUE-0089420. Special thanks are due to our NSF program officer

Myles Boylan in the Division of Undergraduate Education for his

consistent support of this work.

References

Betrancourt,

M., & Tversky, B. (2000). Effect of computer animation on

users’ performance: A review. Travail Humain, 63,

322-329.

Bradshaw, G.L.

(2005). Multimedia Textbooks and Student Learning. Journal

of Online Learning and Teaching, 1. Available at

https://jolt.merlot.org/documents/Vol1_No2_bradshaw.pdf

Deci, E. L.,

Koestner, R., & Ryan, R.M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of

experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on

intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125,

627-668.

Dillon, A.

(2004). Designing Usable Electronic Text (2nd

ed.). London: CRC Press

Moreno, R.,

Mayer, R.E., & Lester, J.C. (2000). Life-like pedagogical

agents in constructivist multimedia environments: Cognitive

consequences of their interaction. In J. Bourdeau & R. Heller

(Eds.), Proceedings of the World Conference on Educational

Multimedia, Hypermedia, and Telecommunications.

Charlottesville, VA: Association for the Advancement of

Computing in Education.

Pashler, H.,

Cepeda, N., Wixted, J., & Rohrer, D. (2005). When does feedback

facilitate learning of words? Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 31, 3-8

Pressler, M.W.

(2004, September 18). Textbook prices on the rise. The

Washington Post, p. E01. Retrieved July 12, 2006, from

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A30151-2004Sep17.html

Rube, K.

(2005). Ripoff 101: 2nd Edition How the publishing

industry’s practices needlessly drive up textbook costs.

California Public Interest Research Group. Retrieved July 12,

2006, from

http://calpirg.org/CA.asp?id2=3660&id3=CA&

Simon, H.A.

(2001). “Seek and Ye Shall Find” How curiosity engenders

discovery. In K. Crowley, C.D. Schunn, & T. Okada (Eds.),

Designing for Science: Implications from everyday, classroom,

and professional settings. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Washburn,

D.A. (2003). The games psychologists play (and the data they

provide). Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and

Computers, 35, 185-193.

Wender, W.F.,

& Muehlboeck, J.-S. (2003). Animated diagrams in teaching

statistics. Behavioral Research Methods, Instruments, and

Computers, 35, 255-258.

Manuscript

received 21 Aug 2006; revision received 26 Oct 2006.

This work is

licensed under a

Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 License

|