|

The Language of Teaching Well

with Learning Objects

Carla Meskill

University at Albany

State University of New York

Albany, NY

USA

cmeskill@uamail.albany.edu

Natasha Anthony

Hudson Valley Community College

Troy, NY

USA

anthonat@hvcc.edu

Abstract

Providing our students access to digital learning objects

is one thing: how we as educators then converse with our

learners about those objects in our online courses – how

we teach using them - is quite another. This paper

discusses the many ways in which instructional

conversations about digital learning objects can be

powerful and powerfully different from how we have

traditionally taught with analog realia (textbooks,

worksheets, overheads) and how such conversations can be

enriched through awareness of digital learning object

attributes and their potential roles in instructional

conversations. A brief introduction to the concept of

instructional conversations is followed by discussion of

the attributes of learning objects that can serve

instructional conversations well. The anatomy of resulting

instructional conversations then serves as the foundation

for direct application in teaching and learning. Samples

of the language that can be used when teaching in concert

with learning objects are then provided and discussed.

Keywords:

instructional conversations, digital learning objects,

language in education, online instructional strategies

Education happens in conversations where the combined

mental resources of teacher and learner are focused on

developing the learner’s understanding.

Neil Mercer, Words and Mind.

2000:169

Language in Teaching and Learning

Language - written, spoken, and hybrid online talk - is

our medium of teaching and learning. It is often an

unstated fact that excellent educators have an excellent

command of language. Moreover, whether it is listening to

an instructor or reading her words, it is those words that

mediate students’ learning. Indeed, teaching and learning

is principally about students mastering the language of

the discipline and thereby becoming literate members of

the target discipline community. This literacy translates

into one’s being skilled at reading, speaking, writing,

and comprehending discipline-specific discourse with some

fluency and it is this fluency that we typically expect of

students in higher education,

be it talk and writing about poetry or talk and

writing about particle physics. We assess the degree to

which students have achieved this fluency through their

performance on examinations and through the extent to

which their written work reflects their control over the

target content as expressed through the discourse norms of

the target discipline community.

Given

this view that language and its disciplinary complexities

are central to teaching and learning, we understand that

simple information is not sufficient for learning. True,

discrete elements are the building blocks for eventual

fluency, but mastery of the target content and the

discipline-specific ways it is expressed is certainly

not about students repeating back easily grasped

absolutes. It is the command of various ways of

understanding and expressing the complexities of the

information that constitutes true learning (Brown and

Campione, 1994; diSessa, 2000; Gee, 2004). Contemporary

teaching and learning is about learners grappling with

messy and ambiguous realities and learning to critically

and articulately make sense of them from a variety of

perspectives in the language appropriate to the content

and context. To do so, students master the language of the

discipline as their primary tool.

As

full-fledged members of our discipline communities, we

have mastered our disciplines’ discourses, both the

written and spoken language and the ways of thinking

germane to that discipline. When we teach, we apprentice

learners in doing the same. We nurture their linguistic

and conceptual growth by initiating them into disciplinary

ways of knowing and communicating. Traditional forms of

this discourse initiation are through students being

passively exposed to classroom/instructional language

whereby instructors are the center of attention and tasks

are instructor-centered. If we consider the optimal ways

that humans learn – through engaging in productive,

generative, problem solving interaction with others in

natural conversation - the traditional,

instructor-centered classroom is indeed an impoverished

form of teaching and learning. This is reflected in Figure

1 which contrasts the language of traditional classroom

instruction with that of natural communication.

| |

Classroom

|

Natural |

| Roles |

Fixed |

Negotiated |

|

Tasks |

Teacher-Oriented |

Group-Oriented |

|

Position-Centered |

Person-Centered |

|

Knowledge |

Focus on

Content |

Focus on

process |

| Accuracy |

Fluency |

Figure

1. Classroom versus natural language (from Kramsch, 1985).

Figure 1 lays out the contrasting features of traditional

classroom language and those of natural conversation. The

impoverishment of traditional classroom language as

compared to the everyday communicative language we thrive

on in social contexts is striking. Where how we

communicate outside the classroom is rich and generative,

traditional classroom language is pointedly not. Where how

we communicate outside of the classroom is oriented to

process and fluency, traditional classroom language is

decidedly not. Where everyday communication tends to be

egalitarian, the teacher-centered, position-centered

nature of traditional classroom language hardly lends

itself to a level playing field. Between these two

contrasting poles lie instructional conversation

strategies that we consider below.

Instructional Conversations

As

we have discussed, excellent teaching and learning is, in

essence, discursive with successful learning being the

mastery of the targeted disciplinary discourses (Cazden,

1988; Sfard, 2000; Wegerif, Mercer, and Dawes, 1999;

Wickstrom, 2003). It follows that optimal formats for

teaching and learning would thus be through what is known

in the field of education as “instructional

conversations”. As defined by Tharp and Gallimore (1988,

1991), the term “instructional conversation” refers to

productive, interactive verbal strategies used by

educators to engage learners in active thinking,

negotiation of meaning, and, consequently, learning. Such

conversations are thinking and speaking joined

dialectically and thus dynamically to generate engagement

in learning processes and thereby mastery of the target

ways of knowing and communicating. According to Goldenberg

(1991), instructional conversation is about discussing

concepts, not ready answers, with a great degree of

freedom while maintaining a focus on specific learning

goals. It is talk that is socially engaging with the

instructor guiding the conversation without dominating

it. It is collective, cumulative talk that aims toward

shared, mutually generated understanding. It is through

engagement in the discourse of the discipline that

learners ultimately gain access to and membership in that

intellectual community. Learning objects, or aspects of

them, can be readily employed as focal materials in the

endeavor. The following sections discuss some of the

attributes of discursive forms of teaching and learning

online and the anatomy of instructional conversations that

make use of learning objects as conversational complements

and tools.

Digital Learning Objects

Where

the real work of online teaching and learning was once

done with words, it can now be done with words in

orchestration with the digital learning objects we link

to, direct learners to manipulate, discuss, assign, and

refer to in our instructional conversations. Where there

are several characteristics of digital learning objects

that make them unique from traditional, analog learning

objects (slides, worksheets, diagrams, for example),

contemporary digital learning objects fundamentally

differ from the analog in that for the most part they are

designed to be subject to individual student/user control

and therefore subject to independent exploration. In

short, digital learning objects do not always lend

themselves to the static referring we have done with work

sheets and overheads for many decades. Because

contemporary learning objects can be under the control of

individual students, directing their attention becomes a

more challenging, but in the long run more effective, form

of instruction. For, if you refer to a particular outcome

in response to particular student input, then the student

is forced to relocate on her running mental map of the

learning object’s properties, its terrain and related

decisions made. In doing so, learners actively dialog with

the learning object. This dialoging opens up opportunities

to employ the discourse of the discipline actively and

interactively. In this regard, digital learning objects

can offer far more stimulation and discourse-rich

referring than the static page of the textbook.

In

addition to this overall dy

– anyone can access any time

Malleable

– anyone can manipulate

Unstable

– what is on the screen may act unpredictably

Anarchic

– meant to be manipulated independently

and

they provide the instructional conversation with

Anchored Referents; that is, what is on the screen

can serve as referential tools (from Meskill, Mossop and

Bates, 2000).

Now

that we have these powerful, dynamic representations in

our respective content areas, objects that potentially

enhance our craft, we are left with the question: How can

the attributes of digital learning objects be linked to

the linguistic and be incorporated into the kinds of

online instructional conversations that affect learning?

Online

Instructional Conversation Strategies with Digital

Learning Objects

Given the vast array of digital learning objects at our

disposal (e.g.,

https://merlot.org), the possibilities for integrating

these into and using them to complement our instructional

conversations with students are indeed endless. Be it for

reinforcing and/or referencing discipline-specific terms

and concepts, or engaging in synthetic talk about complex

processes, the marriage of instructional conversation with

digital learning object can be a solid one.

In our

work with language educators (Meskill and Anthony, 2004,

2005), we have identified a number of online instructional

conversation strategies that can make good use of learning

objects. These are:

-

Referring/Anchoring

-

Saturating

-

Corralling

-

Providing linguistic/thinking tools

-

Modeling

-

Encouraging combinatory or synthetic responses

-

Hyperlinking

-

Internal Dialog.

Referring/Anchoring

One

feature of instructional conversations is “connected

utterances”. These are multiple, connected, interactive

turns in conversation (Goldenberg and Patthey-Chavez,

1995) that can be facilitated through referring to and

thus anchoring language to target properties or

characteristics of digital learning objects. This kind of

instructional conversation strategy takes advantage of the

anchored referent feature of digital learning objects and

may, in addition, exploit the public feature insofar as

what is referred to in the instructional conversation

might well be a publicly shared referent.

EXAMPLE: African Drums

http://www.dancedrummer.com/museum.html

Instructional conversations whose aim is student mastery

of names and properties, both visual and auditory, of

different African drums can make systematic reference to

specific drums and their visual and auditory

characteristics. The discourse of drum identification can

be enlivened in many forms through these anchored

referents. Through instructor language making reference to

the visual, textual, and auditory features of each of

these musical instruments, learners can be guided to

incorporate these terms and concepts into their developing

disciplinary discourse. Figure 2 illustrates potential

references that an instructor working with this learning

object can make between the musical term “gankogui”, its

textual description, physical characteristics, sound

representation, three-dimensional appearance, and sample

uses.

Figure 2.

Referring/Anchoring

Saturating

In

both framing and referring to target content/concepts, we

can also use the instructional conversation strategy

“saturating” (Meskill & Anthony, 2004); that is, using a

target word or words repeatedly throughout our

instructional conversations with students to initiate

their acquisition of this target terminology. Given a

digital learning object that contains a target term,

through instructional conversations instructors can

saturate the discourse with that term. There is no greater

way for learning disciplinary vocabulary than to hear it,

read it, and use it repeatedly as part of and in the

context of disciplinary discourse.

EXAMPLE: Classical Genetics

http://www.dnaftb.org/dnaftb/1/concept/

Repetition of the target term “traits” as a natural part

of instructional conversation about its properties in the

description of the concept, audio, video, animation, and

image titles can anchor learner attention appropriately

and the target term can

become a key term in students’ developing disciplinary

repertoire. Instructional conversations can be saturated

with both the target term and the language that describes

the phenomenon as students explore and manipulate the

object. Saturating then reinforces students’

conceptual/linguistic acquisition of target terms and

phrases.

Figure 3.

Saturating

Corralling

We use

the term “corral” to refer to instructional conversation

that corrals or traps students into using specific target

language forms under study. Corralling is achieved through

asking questions, providing topics and tasks, scaffolding

a student’s spoken and written utterances, etc. The

strategy takes special advantage of the malleable and

anarchic features of digital learning objects in that

students’ independent exploration of the object can be

refocused, “corralled”, through instructional

conversation.

EXAMPLE: Check Mystery

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/educators/course/session1/explore_a.html

The

Check Mystery assignment is intended to help learners

learn how “to make inferences from available evidence to

create explanations”. Learners are directed to scrutinize

series of bank checks for the purpose of building and

strengthening a hypothesis based on the evidence. By

asking learners to summarize what they have learned and

answer questions, instructors corral students into using

the target linguistic forms such as “hypothesis”,

“evidence”, “interference”, etc.

|

|

Figure 4. Corralling |

Providing linguistic tools

Traditional ways of providing linguistic tools -

disciplinary words and phrases – are via word lists,

glossaries, and, of course, lectures. When we involve

digital learning objects in our instructional

conversations, we can readily point to them as

representing the target terminology. Since these

illustrations are often non-static, learners can not only

see contextualized content, but see that content in

action. The kinds of linked information in the following

sample learning object can be nicely reinforced through

instructor instructional conversation that provides the

conceptual/organization guidance learners need to navigate

and make sense of the specialized content.

EXAMPLE: ePSYCH

http://epsych.msstate.edu/index.html

In

ePSYCH, students engage target concepts visually. The

linguistic tools to navigate and make sense of this dense

information can be provided by the instructor through the

construction of tasks that require referencing the correct

vocabulary. Moreover, the features of anchored referents

and the potentially public nature of the object are

supportive in supplying the linguistic tools, in this case

specialized terminology in psychology, for learners to

interact with and master.

Figure 5. Providing Linguistic Tools

Modeling

Instructional conversations mean that we communicate

disciplinarily. Students indeed learn quite a bit about

the target discourse communities that we model in our

instructional conversations. How we incorporate reference

to a specific learning object in conversation can serve to

illustrate and scaffold the target discourse to make it

that much more accessible.

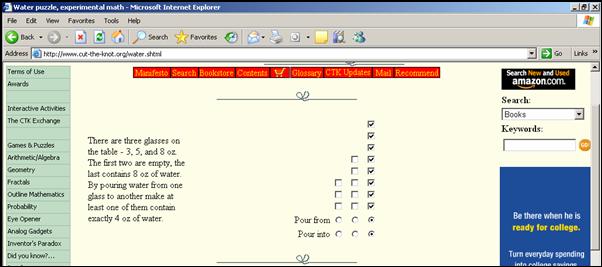

EXAMPLE: The Water Puzzle

http://www.cut-the-knot.org/water.shtml

Describing the problem solving processes that a

mathematician undertakes - constructing hypotheses,

manipulating vare of the learning object allows for

student manipulation and enactment of the language and

thinking that gets modeled through instructional

conversation.

Figure 6.

Modeling

Encouraging synthetic responses

The

multi-dimensional and dynamic nature of many learning

objects lends itself well to encouraging learners to

undertake both active problem solving and the synthetic

thinking that can result. By setting learner tasks that

require investigation of multiple facets of a digital

learning object and eventual synthesis of that experience

which they must carefully articulate, students actively

learn to understand and express using the discourse of the

discipline. A WebQuest is an excellent learning object for

such learning.

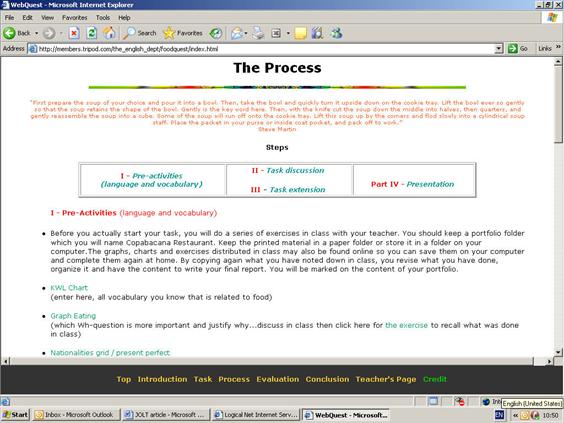

EXAMPLE: Copabacana Restaurant WebQuest

http://members.tripod.com/the_english_dept/foodquest/index.html

In

this WebQuest example, students are assigned a multi-part

task. In the end, students synthesize their work into an

articulate statement of process and findings thus

employing the discourse of the culinary arts in a

communicative way. Both the public nature, whereby

learners interact with one another in public fora, and the

anarchic nature of digital learning objects that render

them open to student exploration and discovery are

particularly well represented by WebQuests.

Figure 7. Encouraging Synthetic Responses

Hyperlinking

Providing hyperlinks as part of instructional

conversations, indeed all kinds of online conversations,

is commonplace. By doing this, we can provide additional

relevant material and information to the topic at hand.

Indeed, contemporary learners are accustomed to hyperlinks

providing supplemental information to the text with the

purpose of deepening or expanding understanding. This

strategy works well with multimedia learning objects in

the way of inserting subtitles, adding a running slogan,

providing headlines from newspapers and magazines, or

adding hyperlinks to documents.

EXAMPLE: Neuroscience for Kids

http://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/neurok.html

Figure 8. Hyperlinking

Internal dialog

This

instructional strategy can be used in online courses when

instructors working with learning objects try to simulate

live interaction. Instructors ask themselves questions and

answer those questions as if they were students being

asked and answering those questions. This instructional

device calls student attention to the concepts expressed

in appropriate, disciplinary discourse.

EXAMPLE: Interactive Mathematics Miscellany and

Puzzles

http://www.cut-the-knot.org/

Comparing two Javascript applets representing a puzzle and

an optical illusion at

http://www.cut-the-knot.org/SimpleGames/CommonThing.shtml,

the instructor involves learners in his internal dialog by

asking and then answering his own questions. By answering

the questions, the instructor calls learners’ attention to

such terms as theorem, measurement, distance, etc.

Figure 9. Internal Dialog

Why

are Instructional Conversation Strategies with Digital

Learning Objects Important?

We see

the use of instructional conversation strategies becoming

increasingly important as 1) online teaching becomes more

widespread; 2) the use of digital learning objects

augments; and 3) a need for training in effective online

instructional language follows suit. In sum, good

instructional communication strategies for nurturing

learners into the target disciplinary discourse that at

the same time capitalizes on the features of digital

learning objects are also important because they can:

-be

responsive to the many studies of online learner

satisfaction that underscore the importance of instructor

engagement through active communication (Swan et al, 2000)

-help

develop learners’ meta-awareness of language forms as they

function in the disciplinary context

-serve

as pedagogical frames when considering if and how learning

objects can be incorporated in teaching

-be

thrown into the mix as informed instructional design

decisions are made

-support the development of ‘metapedagogical awareness’

for educators.

Finally, naming such instructional conversation strategies

with digital learning objects can perhaps serve to anchor

our own interdisciplinary conversations about the craft of

teaching and learning.

Conclusion

When

we return to the core element of teaching and learning –

communication through mutual perspective-taking that gets

mediated through human language – we identify how our

species learns best: from the active negotiation of

meaning with others. Applying this concept to the use of

digital learning objects brings new ways to consider the

substance of teaching and the conversational strategies

that make sense in guiding and immersing our students in

our disciplinary discourse communities. Designing and

conducting conversations that promote learner

participation and consequent development as fluent

communicators is a realm of instruction that digital

learning objects can certainly support and complement

well.

References

Brown,

A., & Campione, J. (1994). Guided discovery in a community

of learners. In K.

McGilly (Ed.), Classroom lessons: Integrating cognitive

theory and classroom practice (pp. 229-270).

Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cazden,

C. (1986). Classroom discourse. Portsmouth, NH:

Heinemann.

diSessa, A. (2000). Changing minds. Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press

Downes,

S. (2004). The rise of learning objects. International

Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning,

1(3). Retrieved on September 19, 2006 from

http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Mar_04/editor.htm.

Gee,

J. (2003) What video games have to teach us about

learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave.

Goldenberg, C., & Patthey-Chavez, G. (1995). Discourse

processes in instruction conversations: Interactions

between teacher and transition readers. Discourse

Processes, 19, 57-73.

Kramsch, C. (1985). Classroom interactions and discourse

options. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 7,

169-183.

Lee,

Y. (2004). The work of examples in classroom instruction.

Linguistics and Education, 15(1-2), 99-120.

Mercer, N. (2000). Words and mind: How we use language

to think together. New York: Routledge.

Meskill, C., & Anthony, N. (2005). Foreign language

learning with CMC: Forms of instructional discourse in a

hybrid Russian class. System, 33(1), 89-105.

Meskill, C., & Anthony, N. (2004-2005). Teaching and

learning with telecommunications: Forms of instructional

discourse in a hybrid Russian class. Journal of

Educational Technology Systems, 33(2), 103-109.

Meskill, C., Mossop, J., & Bates, R. (1999). Bilingualism,

cognitive flexibility, and electronic texts. Bilingual

Research Journal, 23(2/3), 113-124.

Sfard, A. (2002). The interplay of intimations and

implementations: Generating new discourse with new

symbolic tools. Journal of the Learning Sciences,

11(2/3), 319–357.

Swan,

K., Shea, P., Fredericksen, E., Pickett, A, Pelz, W., &

Maher, G. (2000). Building knowledge building communities:

consistency, contact and communication in the virtual

classroom. Journal of Educational Computing Research,

23(4), 389-413.

Tharp,

R., & Gallimore, R. (1991). The instructional

conversation: Teaching and learning in social activity.

Research Report: 2, National Center for Research on

Cultural Diversity and Second Language Learning. Retrieved

on December 7, 2004 from

http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/pubs/cnrcdsll/rr2.htm.

Tharp,

R., & Gallimore, R. (1988). Rousing minds to life:

Teaching, learning, and schooling in social context.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wegerif, R., Mercer, N., & Dawes, L. (1999). From social

interaction to individual reasoning: An empirical

investigation of a possible socio-cultural model of

cognitive development. Learning and Instruction, 9(6),

493-516

Wickstrom, D. (2003). A "Funny" thing happened on the way

to the forum: A teacher educator uses a web-based

discussion board to promote reflection, encourage

engagement, and develop collegiality in preservice

teachers. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy,

46, 414-423.

This

work is based on a 2006 presentation at the MERLOT

International Conference. Ottawa, CA.

Manuscript

received 10 Nov 2006; revision received 1 Mar 2007.

This

work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

2.5 License

|