|

Introduction

Formative evaluation methods for the purpose of

ongoing quality assurance are not accorded the level

of importance that they deserve in e-learning

projects. Often, (advantageous) evaluation data,

such as prestigious access rates, are used

exclusively for external representation, or for

justification or marketing purposes. In these

instances, the quality assurance apparatus is not

meaningfully implemented; instead, it is used to

merely fulfill externally set norms. In addition, in

state-funded projects, evaluation is often

politically “decreed”. Being a requirement for the

funding, the evaluation is financed into the

projects through personnel positions. This

frequently results in a work- and personnel-based

separation of the project work areas design and

evaluation. The consequence of the respective

organizational structures is an insufficient

coordination of the two areas. Hence, the results

that are garnered from evaluation studies often

arrive too late or are foredoomed to insignificance

due to insufficient acceptance by the project

participants.

Evaluation is too often apart from and not a part of

the actual implementation of e-learning. In other

words: design and evaluation detach themselves from

one another – but how can they find their way back

together again? Methods are required that can

produce a scientifically sound and practically

applicable interlocking of the two.

Feeding back the results in the development process

is the primacy of formative evaluation, but the data

often provides no consistent, clear-cut picture.

Interpretation of evaluation results is a creative

and inventive act that should be implemented as an

equitable dialog between the stakeholders involved

in the project.

In this contribution, the personas approach is

described as an example of a creative evaluation

method. Personas as fictional user biographies offer

a comprehensive context for design decisions. The

personas approach is embedded in a generic model for

portal development. As regards methodology, action

research principles frame our work: Addressing

issues which persist in our own practice allows us

to bridge the gap between research and practice (Somekh,

1995).

Literature Survey

As a theoretical framework, findings from evaluation

research in general, and those from works related to

the evaluation of e-learning products and services

in particular, are of interest. Relevant results of

a literature survey are represented in the following

sections.

Evaluation Research

Apart from a few precursors in the 1930s and 1940s,

evaluation research developed as a direction of

empirical social research in its methodological

formulation in the early to mid-60s in the USA in

connection with the reform programs (reform

movement) under President Johnson (“Campaign Against

Poverty”, see Wottawa and Thierau, 1998).

Along with these measures came the task of

scientifically determining the effects of the

reforms, in other words, of conducting a program

evaluation. Since then, evaluation research has

become a permanent fixture - or even ritual (see

Schwarz, 2006) - in the implementation of innovative

political measures and in the review of running

programs.

“The enterprise of evaluation is a perfect example

of what Kaplan (1964) once called the 'law of the

hammer'. Its premise is that if you give a child a

hammer then he or she will soon discover the

universal truth that everything needs pounding. In a

similar manner, it has become axiomatic as we move

towards the millennium that everything, but

everything, needs evaluating.” (Pawson & Tilley,

1997, p. 1)

Historically, Germany, Sweden, and the United

Kingdom are considered first and second wave

evaluation countries where evaluation developed in

the 70s and 80s (see Schröter, 2004;

Luukkonen, 2002).

In German educational studies (pedagogics), the

concept of evaluation first met with disciplinary

obstacles. An empirical orientation went against the

grain of the arts and humanities grounded German

pedagogics, true to the motto „weighing alone

doesn’t make the pig fat“. In other words,

educational system assessments do not equate to

improved or successful system operation. In the

meantime, however, evaluation is carried out as a

matter of course in various domains and the shock

produced by the PISA results in the German

educational system has set the seal on the empirical

foundation of German pedagogics.

What are the implicit and explicit goals of

evaluation? Different authors set different courses.

According to Wottawa and Thierau (1998), there is a

clear pragmatic orientation; evaluation has the

primary goal of improving upon practical measures,

or making decisions concerning them. Kromrey (1995)

defines the term evaluation as the analysis of

programs, methods, projects or organizations by

specialists or experts, who are entrusted with the

role of evaluator and highlights thereby the

personnel-based separation of practitioners and

evaluators. Beywl (1991) gives a definition which

emphasizes the scientific claims and the

reproducibility of the evaluation results.

Pawson and Tilley (1997, pp. 4ff.) draw a history of

evaluation research from the point of view of

methodological change. They identify four main

perspectives on evaluation, namely the experimental,

the pragmatic, the constructivist and the pluralist:

The underlining logic of the experimental paradigm

is to achieve sufficient control to make the basic

causal inference between certain variables secure

(an example of the application of the experimental

paradigm in e-learning research is e.g.

Grubišić, Stankov & Žitko, 2005).

Pragmatic evaluation (also “utilization-focused

evaluation”, see Quinn-Patton,1997) follows the idea

that research ought to be constructed so that it is

better able to be used in the actual processes of

policy making.

The constructivist approach (“fourth generation

evaluation”, comp. Lincoln & Guba, 1989) sees all

beliefs as “constructions” and therefore,

researchers cannot get beyond constructions. Hence,

the role of evaluation is to implement a democratic

negotiation process among the stakeholders of a

project.

Pluralist evaluation ( also “multifaceted approach”

or “mixed methods”, see e.g. a special issue edited

by

Johnson,

2006) tries to combine the rigour of experimentation

with the practical orientation of the pragmatists,

and with the stakeholder-focus of the

constructivists.

Pawson and Tilley (1997) point out that each of

these approaches has specific shortcomings, e.g.

deficits of transferability or generalizability.

Their historical overview of evaluation research as

well as the selected examples cited above reveal the

breadth of the evaluation terminology. There is no

“recipe” to follow for implementing a project or

program evaluation. An appropriate design is to be

“custom tailored” in accordance with the tasks and

objectives of the specific project.

Evaluation of E-learning

Given the diversity of evaluation research as a

whole, what is the “state of the art” of approaches

methods, and instruments when it comes to the

evaluation of e-learning products and services?

Which concrete objectives are pursued by quality

justify">

The annual “Tagung

der Gesellschaft fuer Medien in der Wissenschaft (GMW)”

is a focal point of scientific discussion in the

German-speaking e-learning context. In a document

analysis of GMW Conference volumes from the year

2000 to 2006, 50 contributions could be identified

as having taken up the topic in varying forms. The

topic “evaluation” was explicitly named in three

Call for Papers (2000: “Quality Assurance and

Evaluation Methods“, 2004:“Researched Learning”,

2006: “Quality Aspects”). The bulk of the

contributions deals with the evaluation of a project

and reflects the garnered experiences concerning the

usage of digital media in the respective setting.

What picture does this review draw of the role of

evaluation in e-learning? Even with formative

project evaluations, the subsequent, retrospective

nature still comes conspicuously to the fore. The

role of evaluation in the conceptual phase of an

e-learning design remains “uncharted territory”– in

terms of scientific analysis and practical

applicability. At best, surveys and interviews on

the general acceptance of telemedia-based

instruction are depicted sporadically. Little

attention is paid to ethnographic methods of

usability engineering that explore the information

habits and personal goals of users independent from

a concrete e-learning environment. Thus, the

evaluation often presents a distorted image:

Learners only exist as “users”, whose behavior can

be (re)constructed through, for instance,

interviews, surveys and Logfile analyses, without

taking into account their expanded context beyond

the respective software interface.

Do these findings reflect a “German Sonderweg”? To

take a closer look at the state of the art in

e-learning on an international level, the

proceedings of the conferences E-Learn and ED-Media

were analyzed. Both conferences attract an

international audience and continuously name the

topic within the call for papers. A search query in

the “Education

and Information Technology Library” for the

keyword “evaluation” produced 96 results for the

E-Learn conference (2002-2006) and 165 results for

the ED-Media conference (1998-2006). The role of

evaluation in the total publications indicates the

ongoing relevance of the topic. To capture the

current practices in e-learning projects, a closer

analysis was undertaken for the most recent

proceedings of the year 2006 (Reeves, T. &

Yamashita, 2006; Kommers, & Richards, 2006).

As expected, the publications cover a vide range of

methods and pursue different goals, reaching from

basic research concerned with (quasi-)experimental

testing of hypotheses (comp. e.g. Kiili & Lainema,

2006) to field-oriented content analysis, looking

for patterns in e-learning courses (Khan & Granato,

2006) or systematizing the review criteria in

educational resource distribution websites (Kamei,

Inagaki & Inoue, 2006). Several papers deal with

usability issues – e.g. of children’s websites (Bakar

& Cagiltay, 2006), Open Source Learning Management

Systems (Sanchez & Elías, 2006) or authoring tools

(Gupta, Seals & Wilson, 2006). A conceptual model

for the evaluation of e-learning is proposed by Lam

& McNaught (2006). Their focus lies upon the support

of teachers for the institution-wide implementation

of e-learning. Whilst the paper focuses on the

summative revision of activities, the authors in

principle stress the cyclic character of evaluation.

The broad majority of publications describe case

studies on a specific e-learning design or

intervention. These articles chiefly explain which

technology was used (tablet PCs, 3D-environments,

portfolios, videoconferencing, etc.) in what setting

(e.g. single seminar, course of study,

university-wide, inter-intuitional cooperation) to

what end (first results of evaluation).

Although evaluation of e-learning products and

services is first and foremost directed towards the

goal of improvement, a crucial part of the story is

seldom told: How do findings cross the bridge

between evaluation and design? It appears that

evaluation results are somewhat transmogrified into

design improvements. However, practical experience

shows that one has to pick and chose or at least

prioritize from a variety of results. The next

section tries to systematize the role of evaluation

in the design process by exploring the breadth and

depths of a concrete project, summarizing the

overall flow of events and presenting a specific

method for transforming data into design

decisions.

Case Study

The implementation of e-learning projects in

conjunction with methods of evaluation is analyzed

through a case study on portal development. The

experiences garnered during the implementation of

educational portal

e-teaching.org are transferred into a generic

phase model. The emphasis of the case study lies in

the description of a creative method of quality

assurance, the so-called „personas approach“.

The Educational Portal e-teaching.org

The portal e-teaching.org offers comprehensive

information on didactical, technological, and

organizational aspects of e-learning at universities

and specifically targets university lecturers in

German speaking areas who want to integrate digital

media into their teaching. The content is structured

along the access sections shown in Table 1.

Through these access sections the user is able to

find an individual way to the content based on

specific interests, motivations, and different

levels of knowledge

(also see

English demo version).

Since its launch in 2003, the portal e-teaching.org

has become a well-established information resource

comprising approximately 1,000 Web pages, an

extensive glossary, and diverse multimedia

supplements. It attracts approximately 3000 visitors

per day. For a detailed description of the initial

concept and structure of the portal, see Panke et

al. (2004).

The construction of the portal has unfolded in

roughly two phases: a pilot phase (2003-04) and a

consolidation phase (2005-06).

Table 1: Access sections and learning goals of the

portal e-teaching.org

|

Access Section |

Learning Goal |

|

Teaching Scenarios |

Provides information on how to embed

technologies as educational tools in typical

higher-education teaching situations as e.g.

lectures or tutorials. |

|

Media Technology |

Presents products suitable for implementing

e-learning and describes technologies to compile

and distribute digital learning material. |

|

Didactic Design |

Covers the design of digital media for

educational purposes and describes pedagogical

scenarios for specific tools, e.g. wikis.

|

|

Project Management |

Describes how to organize the development and

implementation of e-teaching projects, e.g.

planning tools, curriculum development etc.

|

|

Best Practice |

Introduces specific university projects and

covers a range from high-end examples to

excellent pragmatic solutions. |

|

Material |

Offers selected collections of literature,

projects, e-journals and other web-based

resources. |

|

News & Trends |

Includes a weblog, which informs about new

content in the portal, as well as current

announcements for e.g. conferences. |

|

My e-teaching |

Gives access to the community and includes

specific local information edited by associated

universities. |

First, during a two-year pilot phase (2003–04)

supported by the Bertelsmann and Nixdorf Foundation,

a prototype of the portal was developed and tested

at two universities. A major accomplishment during

this time was the implementation of specific

functions that allow cooperating universities to

generate a localized version of the portal. Advisory

service teams are able to include location-specific

material to the portal via the university editor, a

key function of the

Plone CMS.

Users of the portal can view content provided by

their individual institution by assigning themselves

to a specific university.

Accordingly, the main emphasis in the consolidation

phase (2005-06) funded by the German Federal

Ministry for Education and Research, was the

distribution of the portal to other universities.

Currently more than 40 universities are cooperating

with e-teaching.org to make the portal a vital part

of their e-learning strategy. An additional aim in

this phase was to motivate users to visit the portal

regularly by providing communication tools to foster

professional collaboration.

Evaluation of the Portal e-teaching.org

During the construction of the portal e-teaching.org,

specific evaluation measures found an application in

conjunction with content-related, technical and

design-oriented decisions in various project phases:

in the first draft, for instance, the results of

comparison research on portals with a similar

thematic spectrum flowed in. The portal prototype

underwent an expert review. Further revisions

resulted from interviews and surveys (see Reinhard &

Friedrich, 2005). The usability of a previous portal

version was assessed through Eye Tracking in

combination with Thinking Aloud. These experimental

results were completed with Logfile data, revealing

the day-to-day use of the portal (see Panke, Studer

& Kohls, 2006).

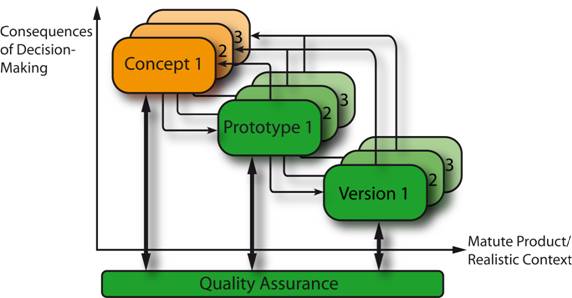

In retrospect, the development of the portal e-teaching.org

can be characterized as a multi-level process, which

is marked by iterations, as well as a cyclical

operation in relation to the triad of (1)

development of a concept, (2) implementation of a

prototype, and (3) use of a portal version. Quality

assurance is viewed as an ongoing process running

parallel to the phases described above, providing

appropriate measures for the various prerequisites

and objectives in the sense of a toolbox (see Fig.

1).

Figure 1: Iterative model of quality assurance in

the construction of portals (Gaiser & Werner, in

press)

The flow of evaluation and implementation pictured

in figure 1 reflects specifically the

development of educational portals. Nevertheless, it

corresponds to the prevalent form of product

development in the e-learning sector in general.

Since the 1980s, results of formative evaluation and

various forms of user testing are accepted as

important inputs to e-learning development, and the

iterative design cycle is an established modus

operandi.

A central aspect of this model is the chronological

dimension: The decisions that are made at an early

stage in the development cycle have far-reaching

consequences, as they substantially contribute to

determining the course of the future project. The

further along a project is, meaning the more

conceptual, technical design or content-relly: Arial">

Hence, the role of evaluation in the conceptual

phase of e-learning designs is of utmost importance

due to the wide-reaching influence of decisions

rendered. Unfortunately, as the literature review

presented in

section one reveals, the current practice of

evaluation is not focused upon the beginning of a

project. Evaluation seldom enters the stage,

before a first prototype is developed. In the

case study, the authors aim to show how creative

methods of data aggregation can be used to inform

specifically the conceptual development – the

initial design of product features.

As a further functionality of e-teaching.org –

forming a further cycle in the portal development

process – the implementation of a domain-specific

online community was undertaken in the years 2005

and 2006. The application of the personas approach,

which will be described in further detail in the

next section, played an important role in

aggregating evaluation data for the conceptual

planning of these new features.

Personas

The use of personas – fictional persons – to

represent an abstract consumer originally derived

from the field of marketing and, since the late

1990s – inspired by a publication by Cooper (1999) -

has also been applied within the framework of

software engineering to expand other usability

methods (Pruitt & Grudin, 2003).

The personas approach gives the developer an

authentic glimpse into the potential user’s world by

bringing abstract target group information to life

through the presence of a specific user (Junior &

Filgueiras, 2005). Acting as a kind of “projection

screen”, personas aid in identifying (informational)

needs and possible behavioral patterns of the target

group. The comprehension of informational

requirements and mental models is essential for the

design of complex information products and services

(Sinha, 2003). Useful functionalities can be derived

in conjunction with the needs, interests and

possible actions of the personas. Personas and their

legends deliver the necessary context for numerous

design decisions in the creative process. The

application of the personas method can also support

the communication within interdisciplinary developer

teams and offer a guideline in the development

process (Ronkko, 2005). Critique of the method is

especially appropriate when personas replace actual

user participation in the design process (Ronkko,

2005).

To fulfill the standards of a scientific method and

in order to pose an authentic copy of the real

users, Pruitt and Grudin (2003) suggest basing

personas on qualitative and quantitative data

gleaned from target group investigations. The

fictional characters created for the community

design of e-teaching.org were derived from data that

was collected from an online survey, from interviews

with users and advisors, and from feedback e-mails.

Online survey: From April 2004 to November 2005, an

online survey was imbedded into the website. In

total, 237 users completed the questionnaire.

Interim analyses were carried out to monitor central

indicators for website quality, e.g. usability of

navigation, suitability of content, perceived

reliability and interestingness. In the process of

composing the personas, the online survey provided

the team with socio-demographical data on the

background of the portal’s regular visitors. The

design team learned for example, that the portal is

also a popular source of information for students

interested in e-learning pedagogy. Another aspect

which was taken up in the personas creation was the

balanced gender ratio among the users.

Interviews: In November and December 2003, ten

qualitative interviews with consultants and clients

of central e-learning units at the project’s two

initial partner universities were carried out. This

data, initially used to find indicators or potential

obstacles for the acceptance of the website in the

university context, was a rich source for the

“hidden” motives of users.

Feedback e-mails: Roughly 150 feedback e-mails were

received between the launch of the portal in August

2003 and the beginning of developing the personas

concept in spring 2005. These e-mails were used to

mirror our first sketches of personas with flesh and

blood users of the portal. The e-mails were

clustered into four groups, each represented by one

archetypical user. This procedure resulted in the

fictional users Alfred, Tanja,

Beate and Philipp.

The finishing touch was accomplished in a series of

group discussions with the whole design team.

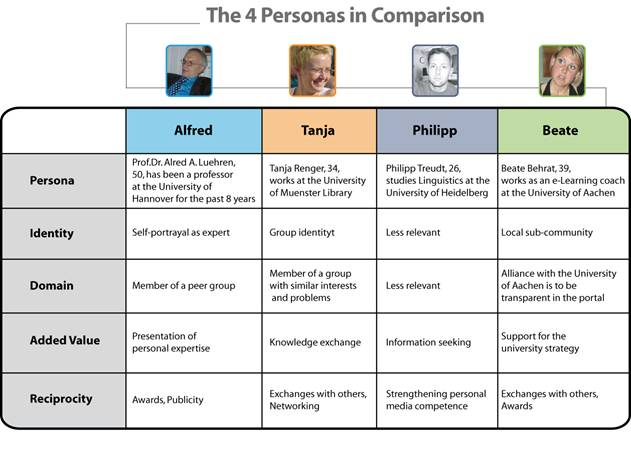

In a next step, their fictional biographies were

connected with core design dimensions of community

building. The role of the personal identity, the

technical domain, the individual added value, as

well as the comparison mechanisms between active and

less active participants (reciprocity) were analyzed

in detail. The personas Alfred, Tanja, Philipp and

Beate represent various target groups within the

community (compare Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Matching Personas and Community Design

Dimensions

People like Tanja are important for the process of

community building, as they are interested in an

intensive exchange of ideas. As part of her advisor

capacity, Beate has time budgeted for participation

in synchronous online-events and for acting as

moderator. Alfred’s expertise is an important input

factor for the community. His reputation is crucial

for the construction of a common community identity.

In order to expand the community, Philipp’s

interests should also be met, as he will also

contribute to the community as his expertise grows.

Results

From the developers’ point of view, the special

value of the personas lay in the improved

communication and depth of understanding among the

various protagonists. Design and implementation of

the community functions required numerous detail

decisions that could hardly be reached directly on

the basis of the evaluation data. Additionally,

there is the respective discipline-specific

viewpoint held by individual team members. For

questions, such as “Would Beate use this function in

this manner?”, the personas created a common

framework of reference and prepared the ground for a

discussion of the function in detail.

As a result of the design process based on the

described personas, the community section of e-teaching.org

was equipped with communication and awareness

functions addressing specific needs of the target

group. For instance, virtual business cards were

implemented that offer the possibility of announcing

conference participation or research interests.

Expert chats, online trainings and virtual lectures

offer further qualification opportunities. Annual

partner workshops with e-learning consultants

promote networking among the e-teaching.org partner

universities. The community was launched in May of

2006 and currently (May 2007) has more than 500

members. Figure three pictures the steady growth of

the community within its first year.

Figure 3: Members of the e-teaching.org community

(total number)

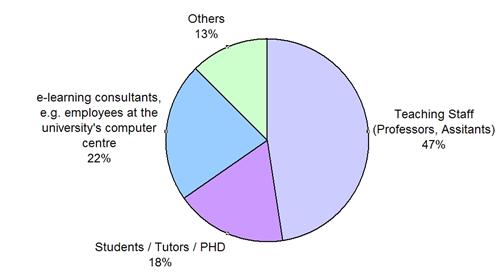

Have the personas actually helped to improve the

sociability of the community and does the portal e-teaching.org

appeal to its target group? Analyzing the virtual

calling cards reveals that the different user

segments represented by the fictional

personas can also be found in the real

community (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Professions of community members derived

from their profiles (n=287).

Recapitulating our experiences, the personas proved

to be a valid instrument to feed back the formative

evaluation data into the development process.

Discussion

In the example of the development of community

functions for the portal e-teaching.org, personas

were used for consolidating evaluation data from

various sources and for making the design process

fruitful. This leads to the question of how generic

or transferable the personas approach is for other

kinds of e-learning products or services.

Judging from the experiences of the case study,

personas should only be applied within the framework

of larger project teams. Discussion concerning their

authenticity and ability to represent a larger group

of users is a decisive ingredient for ensuring the

quality of the personas. Otherwise, there is the

danger that a single designer tailors the ideal user

biography for his personal arguments, thereby

rendering the method meaningless.

The personas approach is also recommended whenever

the relationship user-designer is anonymous. A

teacher who designs learning materials for a

comprehensible group of recipients – i.e., a small

seminar group, comprising a dozen participants –

should work more towards direct participation of

users. In contrast, should the task concern making

conceptual decisions at the university level, be it

the design of a website or the organization of a

course of studies, evaluation data aggregated to

personas could depict a living image of the target

group.

An advantage of fictional biographies is that they

remove the personal level by abstraction. Through

their mediating character, personas can be useful

when the acceptance of evaluation results is

endangered by personal resistance, power struggles

and animosities. Furthermore, the narrative context

can help the project team to develop potential

explanations or working hypothesis for contradictory

or confusing data, thereby delivering input for

ongoing research.

Conclusions

In this contribution, experiences from evaluation

research and practice were described and applied to

the portal domain. Tracing the roots and history of

research and discussion on evaluation back to the

Sixties, one can see that the topic has not lost its

potential to inflame controversial debates on

appropriate methods and adequate consequences ever

since. However, the question of how to include

routines of quality assurance into the everyday

practice of designing learning material is rarely

reflected in the current debate. Within the

e-learning community, one can observe that

evaluation often has an external function (e.g.

justification of a certain approach). The internal,

formative role needs to be emphasized – especially

when developing concepts for e-learning content and

infrastructures. Additionally, the frequently

encountered personnel-based separation of evaluation

and design presents a fundamental development

problem. Isolated processing of the task areas only

makes sense when the control function of an

evaluation is in the foreground.

Through the use of a case study, general reflections

on the role of evaluation in the project progression

were presented, along with the application of a

specific method for purposes of creative design. The

case of e-teaching.org shows how personas can

aggregate formative evaluation data - some of which

is partially garnered through other motives. It was

argued that this instrument has potential for the

creative development of a new product or service.

To turn inanimate data into a vivid picture of the

needs and expectations of users or learners, the

Personas approach is a convincing method. It helps

the development team to keep in mind that visiting a

portal or using software is not an end in and of

itself. Therefore, it is vital to also view the

users “outside” the human-computer interface and to

perceive them as whole persons, who pursue their own

goals – with, without or counter to the product that

was designed for them.

References

Bakar, A. & Cagiltay, K. (2006). Evaluation of

Children's Web Sites: What Do They Prefer?. In

Proceedings of

World Conference on Educational Multimedia,

Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2006

(pp. 569-574).

Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Beywl, W. (1991). Entwicklung und Perspektiven

praxiszentrierter Evaluation. In:

Sozialwissenschaften und Berufspraxis, 14 (3),

pp. 265 - 279.

Cooper, A. (1999). The Inmates Are Running the

Asylum: Why High Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and

How to Restore the Sanity. Sams-MacMillan

Computer Publishing.

Gaiser, B. & Werner, B. (in press).

Qualitätssicherung beim

Aufbau und Betrieb eines Bildungsportals. In B.

Gaiser, F.W. Hesse, & M. Lütke-Entrup, (in press).

Bildungsportale – Potenziale und Perspektiven

netzbasierter Bildungsressourcen. München:

Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag.

Johnson, R. B. (2006, Ed.). New Directions in Mixed

Methods Research. RITS Special Issue, 13(1).

http://www.msera.org/rits_131.htm

[last checked 07/05/30].

Grubišić, A., Stankov, S., Žitko, B. (2005).

Evaluating the educational influence of an

e-learning system, Proceedings of the

International Conference CEEPUS Summer School 2005,

Intelligent Control Systems (pp.151-156).

http://www.pmfst.hr/~ani/radovi/2005CEEPUS.pdf

[last checked 07/05/30].

Gupta, P., Seals, C. & Wilson, D. (2006). Design And

Evaluation of SimBuilder. In T. Reeves & S.

Yamashita (Eds.),

Proceedings of

World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate,

Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education 2006

(pp. 205-210).

Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Kommers, P. & Richards, G. (Eds.), Proceedings of

World Conference on Educational Multimedia,

Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2006.

Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Kamei, M., Inagaki, T. & Inoue, K. (2006).

Evaluation Criteria of Digital Educational Materials

in Support sites. In Proceedings of World

Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and

Telecommunications 2006 (pp. 75-79). Chesapeake,

VA: AACE.

Kiili, K. & Lainema, T. (2006).

Evaluations of an Experiential Gaming Model: The

Realgame Case. In

Proceedings of

World Conference on Educational Multimedia,

Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2006

(pp. 2343-2350).

Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Khan, B. & Granato, L. (2006).

Comprehensive Program Evaluation of E Learning. In

Proceedings

of World Conference on Educational Multimedia,

Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2006

(p. 2126).

ndlungsprogrammen und die

Schwierigkeiten ihrer Realisierung. In

Zeitschrift für Sozialisiationsforschung und

Erziehungssoziologie. 15 (4), pp. 313 - 336.

Lam, P. & McNaught, C. (2006). A Three-layered

Cyclic Model of eLearning Development and

Evaluation. In

Proceedings of

World Conference on Educational Multimedia,

Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2006

(pp. 1897-1904).

Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1989). Fourth

generation evaluation. Newbury Park: Sage.

Luukkonen, T. (2002). Research evaluation in Europe:

state of the art.

In Research Evaluation, 11 ( 2), pp. 81-84.

Panke, S., Wedekind, J., Reinhardt, J. & Gaiser, B.

(2004). www.e-teaching.org–Qualifying Academic

Teachers for the E-University. In D. Remenyi

(ed.).

Proceedings of ECEL 2004, European Conference on

e-Learning, (pp. 297-306).

Reading, UK: Academic Conferences International.

Panke, S., Studer, P., & Kohls, C. (2006). Use &

Usability: Portalevaluation mit Eye-Tracking und

Logfile-Daten. In M. Mühlhäuser, G. Rößling, & R.

Steinmetz (Eds.), Proceedings DELFI 2006. 4te

Deutsche e-learning Fachtagung Informatik (pp.

267-278). Bonn: Gesellschaft für Informatik.

Panke, S., C. Kohls, & Gaiser. B. (2006).

Participatory Development Strategies for Open Source

Content Management Systems.

Innovate

3 (2).

http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=326

[last checked 07/05/30].

Pawson, R. & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic

Evaluation. London: Sage.

Pruitt, J. & Grudin, J. (2003). Personas: practice

and theory. In Proceedings of the 2003 Conference

on Designing for User Experiences. New York: ACM

Press.

Quinn-Patton, M. (1997). Utilization-Focused

Evaluation.

London: Sage.

Reinhardt, J., & Friedrich H. F. (2005). Einführung

von E-learning in die Hochschule durch

Qualifizierung von Hochschullehrenden: Zur

Evaluation eines Online-Qualifizierungsportals. In

D. Tavangarian & K. Nölting (Eds.), Auf zu neuen

Ufern! E-learning heute und morgen (pp.

177-186). Münster: Waxmann.

Ronkko, K. (2005). An Empirical Study Demonstrating

How Different Design Constraints, Project

Organization and Contexts Limited the Utility of

Personas. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences

(Hicss'05) - Track 8 - Volume 08 (pp. 220.1).

Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society,

Reeves, T. & Yamashita, S. (Eds.), Proceedings of

World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate,

Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education 2006.

Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Sanchez, J. & Elías, M. (2006). Usability Evaluation

of an Open Source Learning Management Platform. In

T. Reeves & S. Yamashita (Eds.),

Proceedings of

World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate,

Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education 2006

(pp. 1772-1779).

Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Schröter, D. (2004). Evaluation in Europe: An

Overview. Journal of Multi Disciplinary

Evaluation 1(1). Online, Available:

http://www.wmich.edu/evalctr/jmde/content/JMDE_Num_001.htm#_Toc86719007

[last checked 07/03/05].

Schwarz, C. (2005), Evaluation als modernes

Ritual. Zur Ambivalenz gesellschaftlicher

Rationalisierung am Beispiel virtueller

Universitäten, Dissertation.

Münster: Waxmann Verlag.

Sinha, R. (2003). Persona development for

information-rich domains. In CHI '03 Extended

Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

(pp. 830-831). New York: ACM Press.

Somekh, B. (1995). The Contribution of Action

Research to Development in Social Endeavours: a

position paper on action research methodology.

British Educational Research Journal. 21 (3),

pp. 339-55

Wottawa, H. & Thierau, H. (1998). Lehrbuch

Evaluation, Bern: Huber Verlag.

|