|

Introduction

Instructors often integrate case studies,

assignments and quizzes into their classes for many

different reasons. Case studies and assignments can

help students apply information previously learned

in class to solve new problems. Through the

analysis of data, interpretation of results and

reading of specific articles, students may probe

deeper into a particular topic than through lecture

alone. Research indicates that understanding is

more likely to develop when students engage in

activities such as analysis, evaluation,

interpretation, prediction, and explanation

(Bransford, Brown & Cocking, 1999; Coleman, 1998;

Coleman, Rivkin & Brown, 1997). Quizzes are also

often used as an incentive for students to keep up

with the material between exams and can provide

students with valuable formative feedback on what

concepts they need to review. Moreover, assignments

and quizzes can be used by faculty for assessment of

student learning and identification of

misconceptions. However, the time required to grade

quizzes may impede an instructor’s ability or desire

to give assignments and quizzes, especially in

larger introductory courses. The objective of this

project was to create homework assignments for large

classes that could be evaluated through the use of

online quizzes with minimal effort by the

instructor. Moreover, we monitored student use of

online quizzes, allowed students to retake quizzes,

and evaluated the relation of improvement in quiz

scores and time between attempts.

Literature Survey

Most instructors teaching courses in the life

sciences would like to engage students in learning

outside of class through reading assignments and

other activities. However, large class sizes,

especially in introductory biology courses, make

instructors reticent to assign homework because of

the inordinate amount of time required to grade and

assess assignments. Computer-based assignments and

assessment offer a mechanism to minimize the time

required by instructors to evaluate student

performance.

Recent research has focused on comparing the

effectiveness of online and traditional lecture or

paper-based teaching methods. Much of this work has

been done in the physical sciences (astronomy,

chemistry and physics) where students can be given

numerical problems to solve, or explain phenomena

using equations. In several studies there was no

difference in scores between homework assignments

given in a traditional paper-based format versus

those given online (Cole & Todd, 2003; Bonham et

al., 2003; Allain & Williams, 2006, Bunce, et

al., 2006). However, Dufresne et al.

(2002) reported a slight increase in test scores by

students completing assignments online. Hence,

these results suggest that completing homework

online is neither inferior nor superior to

traditional paper-based assignments. However,

online homework may offer a substantial advantage to

the instructor through a reduction in the amount of

time required in grading.

A challenge of online quizzes in the life sciences

is that the issues being discussed cannot always be

reduced to numerical answers or equations and are

often much more conceptual or descriptive than those

in the physical sciences. As a result, online

quizzes may become tests of rote memorization and

factual recall. One solution to this problem is to

give students open-ended assignments and homework

questions, and then give an online quiz to assess

student completion of the homework assignment and

understanding of the material. Moreover, this

permits instructors to show connections between

biological concepts and news stories in the popular

press, which allows students to see how the

theoretical concepts they are learning in class are

applied in the real world. Such issues-based

biology courses are becoming more common, especially

for non-majors (Stover & Mabry, 2005).

Methods

The authors linked class assignments with online

quizzes in a 14-week non-majors introductory biology

course which had two to three lecture sections with

80 to 120 students in each section. During the

semester, students completed 18 to 20 assignments

(Table 1) and online quizzes on the content from

each assignment. Students were allowed two to five

days to complete the assignment and quiz. Each quiz

consisted of five multiple-choice questions chosen

randomly from a pool of 10 to 20 questions based on

the assignment. Once a student began a quiz, they

had five minutes to complete it. This time limit

was intended to minimize students’ ability to look

up answers rather than recalling the information.

Students were allowed to take each quiz twice, and

their highest score was recorded. Because the

questions were generated randomly, the second quiz

differed from the first. Students immediately saw

their quiz results upon completion, although the

correct answers to questions were not revealed.

Students then had the option of reviewing the

assignment before taking the quiz a second time;

students could re-take the quiz immediately or delay

taking the quiz up until the deadline for the

assignment. Providing students with a second

chance to learn from their mistakes is an effective

way to increase proficiency using online assignments

(Hall et al., 2001). The quizzes were

automatically generated, scored, and grades were

recorded by a web-based course management system,

Desire2Learn (D2L). Students were asked to complete

course assignments and online quizzes once or twice

per week. After creating the assignments and

writing the quiz questions, instructor oversight was

minimal. The D2L system also recorded the time each

student took each quiz and the answers they choose,

which can be useful assessment information for

instructors.

The designs of the assignments varied, but all

assignments included a set of questions for students

to consider after they read an article or analyze

data. In addition, each assignment addressed a

topic being covered simultaneously in lecture.

The online quizzes then tested the students’

understanding of the assignment and the associated

questions they were asked to answer. The students

did not turn their assignments in to the instructor,

and the instructor did not manually grade quizzes.

Our assignments were based on diverse sources (Table

1), including articles from the popular press (New

York Times, etc.), Scientific American and readings

from the textbook. Several assignments were linked

to websites that included simulations or data sets,

while other assignments required students to use

both text and online material. Thus, one of the

strengths of this approach is that instructors can

incorporate a variety of material from different

sources into assignments.

Table 1: Topics for General Biology Assignments and

Quizzes

|

Quiz |

Assignment – Article |

Assignment - Website |

|

1 |

Scientific Method |

Graduate Student Experiment |

AquaRush |

|

2 |

Populations |

|

US Census, Nationmaster |

|

3 |

Community Interactions |

NYT article on “In the Rockies, Pines Die and

Bears Feel It” |

|

|

4 |

Nutrient Cycles |

Discover article on “The Nitrogen Bomb” |

|

|

5 |

Obesity Epidemic |

|

Centers for Disease Control, National Heart,

Blood and Lung Institute |

|

6 |

Biological Molecules |

NYT article on “Science's Quest to Banish Fat in

Tasty Ways” |

Cells Alive, Wisc-Online |

|

7 |

Enzymes and Energy |

From textbook, “Missing Molecule Makes Mischief”

on PKU. |

Newborn screening tests, Enzyme Activity. |

|

8 |

Respiration and Metabolism |

|

Centers for Disease Control, Ben’s Bad Day |

|

9 |

Photosynthesis |

From textbook, why chlorophyll is green, meat is

red and blood from mussels is blue. |

Fall Colors, |

|

10 |

Meiosis |

From textbook, what determines gender |

PBS |

|

11 |

Mitosis |

NYT article “Your Body Is Younger Than You

Think” |

|

|

12 |

Genetics |

Hemophilia case study from SUNY |

SUNY |

|

13 |

Molecular Biology |

From textbook, cystic fibrosis |

OMIM, Hemophilia background, Cystic fibrosis

background |

|

14 |

Biotechnology |

Scientific American article “The Land of MILK &

MONEY” |

|

|

NYT article “Embryonic Cells, No Embryo Needed:

Hunting for Ways Out of an Impasse” |

|

15 |

Evolution |

|

|

16 |

Natural Selection |

|

Natural Selection Simulation |

|

17 |

Speciation |

|

Speciation Simulation |

|

18 |

Human Evolution |

Scientific American article “Lucy’s Baby” |

|

Results

Because the quizzes and assignments were linked and

were developed simultaneously, there was not any

direct pre- and post-assessment of student

learning. Instead the goal of this project was to

find a reasonable method to create graded homework

assignments for large classes and monitor student

use of the quizzes. The “online attendance” of 240

students taking 18 quizzes over three semesters was

95.7% and decreased slightly over the course of the

semester (Figure 1).

Students were asked to rate six different teaching

methods used in the class by evaluating the

following statement “The ______ helped me to

understand the material.” as strongly disagree,

disagree, neutral, agree, or strongly agree (Figure

2). Results from 140 students surveyed indicated

that lectures and lecture notes were ranked most

favorably, while the textbook and in-class

activities were ranked least favorably. Student

evaluations of online assignments and quizzes were

tied with personal response system questions, and

the majority of the class either agreed or strongly

agreed that these teaching techniques helped them to

understand the material.

Figure 1. Percentage of students taking each quiz.

Values are the mean number of students over three

semesters (n=240).

Several interesting patterns were observed in

student quiz-taking strategies and behaviors.

Students were allowed to take the quiz twice, with a

five minute time limit per quiz, and only the

highest score was recorded. Students getting a

perfect score were encouraged to take the quiz a

second time for practice, yet only 19.6% took this

advice. Students missing at least one question on

the quiz were advised to take the time to review the

assignment again before using up their second

attempt. Of those who missed at least one question

on their first attempt, 1.7% did not try again,

74.9% completed their second attempt within 10

minutes (average time = 4.6 minutes), and 23.4%

completed their second attempt at least 10 minutes

after their first attempt (average time = 21.6

minutes). Given the five minute time limit to take

the quiz, it is unlikely that students had time to

review the assignment in less than 10 minutes, and

these students most likely took the quiz a second

time immediately after their first attempt. On

average, these students scored half a point better

on their second attempt than their first, suggesting

that getting some immediate feedback from the first

attempt did improve their performance on the second

attempt. However, students who took at least 10

minutes between attempts scored twice as well on

their second quiz (Figure 3, p=1x10-6 by

t-test), consistent with improved performance after

reviewing the assignment.

Figure 2. Introductory Biology student ratings of

different teaching methods. Students were asked if

each of the teaching methods helped them to

understand the material using the scale indicated in

the legend. (n=140).

Figure 3. Time lapsed between quiz attempts vs.

mean change in score between attempts. Numbers in

parentheses indicate the number of students in each

category.

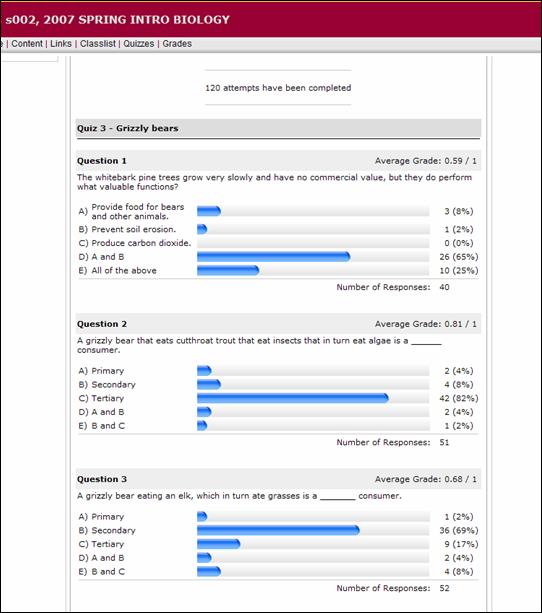

Overall the instructors felt that the additional

effort involved in generating the assignments with

linked quizzes was worthwhile. The students seemed

more engaged in the material, and were better

prepared for problem-solving exam questions. The

authors were also able to give students formative

assessment by reviewing the quizzes in class each

week, as the D2L site gives instructors information

on how many students chose each answer for each

question (Figure 4). In this way instructors can

identify where the class was having problems, and

which wrong answers were being chosen. This

feedback could then be used in class, and any

confusing topics discussed again.

Figure 4. Quiz results based on the New York Times

article, “In the Rockies, Pines Die and Bears Feel

It.” By Charles Petit, January 30, 2007.

Discussion

Benefits to the Students

The authors feel that the students benefit from the

online assignments and quizzes in several ways.

This approach requires the students to work with the

subject material presented in lecture four to five

times between exams. This reduces the amount of

last-minute cramming that many first-year students

rely on to prepare for exams. The “online

attendance” of 95.7% in the current study was

similar to other studies of student performance of

online assignments. For example, Riffel & Sibley

found that 93% of students participated online but

only 78% physically attended class. Moreover, these

online assignments and quizzes allow students to see

how the concepts they are learning in lecture apply

in the real world. The use of science articles from

the popular press reinforces the concept that

subjects covered in class appear in the news every

day and , as an informed citizen, they should be

able to read a newspaper article and understand it.

Finally, the students get direct formative feedback

of their progress in the class well before any

exams. Formative assessment is more valuable than

summative assessment, as students have time to learn

from their mistakes and correct any misconceptions

early on in their learning process (Cooper et al.,

2006).

Benefits to the Teacher

As teachers we frequently struggle with ways to

engage our students in the subjects we teach.

Instructors often strive to involve students in

hands-on exploration, discussion, and writing.

However,

given large class sizes and other instructional

responsibilities, such teaching strategies are

difficult to implement.

The use of online assignments, coupled with online

multiple choice quizzes written to assess student

understanding of the key points of the assignment,

allows instructors to increase student engagement in

an efficient manner. Most of the effort in this

project was in creating the assignments and

accompanying questions, writing the quiz questions,

and programming this into D2L. Since then, the same

assignments and quizzes have been used in multiple

lecture sessions for three years. Each year a few

of the assignments and quizzes are changed as new

articles become available. The use of the

assignments and quizzes has also allowed removal

from lecture of some material that required only

rote memorization by the students. Instead,

students visit websites that contain this content,

thus making time for in-class assignments and

questions. One limitation of this approach is a

reliance on multiple choice questions. Instructors

can choose questions that require analysis of data,

instead of reciting definitions or content.

Conclusions

Linking diverse assignments, including readings,

case studies, analysis of databases and websites

with an online quiz allows instructors to more fully

engage students and encourages them to explore

subject material in a more complex manner, while

requiring only a modest increase in instructional

effort. This allows an instructor to increase the

frequency of assignments, keeping the students

engaged in the material between exams. It also

allows students to explore multiple topics in depth,

which is especially useful in a broad introductory

class. With the diverse format of the assignments,

this method should be applicable in many different

disciplines in both science and non-science

courses.

References

Allain, R. and Williams, T. (2006). The

Effectiveness of Online Homework in an Introductory

Science Class. Journal of College Science

Teaching, May/June, 28-30.

Bonham, S.W., Deardorff, D.L., Beichner, R.J.

(2003). Comparison of student performance using web

and paper-based homework in college-level physics.

Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 40(10),

1050–1071.

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L. & Cocking, R.R.

(Editors). (1999). How People Learn: Brain, Mind,

Experience and Schooling. Washington, DC: National

Academy Press.

Bunce, D.M., VandenPlas, J.R. and Havanki, K.L.

(2006). Comparing the Effectiveness on Student

Achievement of a Student Response System versus

Online WebCT Quizzes. Journal of Chemical

Education, 83(3), 488-493.

Cole, R.S. and Todd, J.B. (2003). Effects of

Web-Based Multimedia Homework with Immediate Rich

Feedback on Student Learning in General Chemistry.

Journal of Chemical Education, 80(11), 1338-1343.

Coleman, E.B. (1998). Using explanatory knowledge

during collaborative problem solving in science.

Journal of the Learning Sciences, 7(3-4), 387-427.

Coleman, E.B., Rivkin, I.D. & Brown, A.L. (1997).

The effect of instructional explanations on learning

from science texts. Journal of the Learning

Sciences, 6(4), 347-365.

Cooper, S., Hanmer, D. and Cerbin, W. (2006).

Problem Solving Modules in Large Introductory

Biology Lectures Enhance Student Understanding.

American Biology Teacher, 68, 524-9.

Dufresne, R., Mestre, J., Hart, D.M., Rath, K.A.

(2002). The effect of web-based homework on test

performance in large enrollment introductory physics

courses. Journal of Computers in Mathematics and

Science Teaching 21(3), 229-251.

Hall, R.W., Butler, L.G., McGuire, S.Y., McGlynn,

S.P., Lyon, G.L., Reese, R.L. and Limbach, P.A.

(2001). Automated, Web-Based, Second-Chance

Homework. Journal of Chemical Education, 78(12),

1704-1708.

Perkins, D.N. (1998). What is understanding? In M.

Stone-Wiske (Editor), Teaching for Understanding:

Linking Research With Practice. San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass.

Riffell, S.K. and Sibley, D.F. (2004). Can Hybrid

Course Formats Increase Attendance in Undergraduate

Environmental Science Courses? J. Nat. Resour. Life

Sci. Educ., 33, 1-5.

Stover, S. and Mabry, M. (2005). Merging Science

and Society: An Issues-Based Approach to Nonmajors

Biology. Journal of College Science Teaching,

Jan/Feb, 40-43.

|