|

| MERLOT

Journal of Online Learning and Teaching |

Vol. 3,

No. 3, September 2007

|

|

|

|

Developing a Public

Health Web Game to Complement Traditional

Education

Methods in the Classroom

Eileen O’Connor

School of Human Kinetics

Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa

Ottawa, ON CA

Karen Phillips

Health Sciences Program

Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa

Ottawa, ON CA

|

|

ABSTRACT

Infectious disease outbreaks, whether natural or deliberate,

constitute a growing health concern. The impending

reality of this situation is indicative of the

exigency in which the government recently created

the Canadian Public Health Agency. As with other

countries, Canada is committed to enhance its

capacity to respond to emergencies through increased

investment in the interdisciplinary training of

medical and public health professionals. This

article describes our initiative to create an

innovative scenario-based web game of an infectious

disease outbreak to be used in medical and public

health university-level courses. By providing

real-life, concrete examples of health crisis

situations, students will develop strong

critical-thinking skills while examining the cause

and effect relationship of actions. Ultimately, our

goal is to transfer current knowledge on best

practices in emergency preparedness to

university-level students.

KEYWORDS:

Emergency management, epidemics, goal-based

scenarios, infectious disease, public health,

simulation, game, students, training, online

education

|

|

INTRODUCTION

Infectious disease outbreaks, whether natural or

deliberate, constitute a growing health concern.

Recent terrorist attacks in London and Madrid, or

the natural disasters in Peru, the Hurricane Katrina

in the US Golf Coast, the Tsunami in Indonesia, or

disease outbreaks like the 2003 SARS outbreak in

Toronto, all highlight the need for better training,

communication, integration and improved emergency

responsiveness. Health care workers, researchers,

and policy advisors recognize the need for enhanced

collaborative and coordinated communications and

training for healthcare workers as ‘first

responders’. There is also a need to establish

better training guidelines and raise public

awareness of how to manage and contain infectious

diseases. Thus, the genesis of this project stems

from the need to engage and train future healthcare

workers, health policy analysts and first responders

to respond to an infectious disease outbreak. Our

public health scenario-based game, OUTBREAK!

serves to fill this gap by offering students the

chance to role play and test their abilities in

understanding, mitigating and managing an infectious

disease outbreak in a large urban city.

This paper discusses the developmental stage of

developing the game prototype for OUTBREAK!

Future phases in this game development include the

testing, evaluation and subsequent revision of the

prototype once it has been tested in a

computer-equipped undergraduate health sciences lab

classroom.

Design Strategy

Training health care specialists through e-learning strategies and

role-playing games has proven to be widely

successful. As Garris,

Ahlers and Driskell (2002) contend, these

games are both engaging

and instructive in their design, with students

demonstrating a high retention of new material

acquired. In the Canadian context, there are

few public health web-based scenario games

developed, thereby providing a substantial niche for

our scenario-based game.

As an interactive and visual tool, OUTBREAK! is designed to engage

students whose learning styles are best served

though the use of concrete examples and role playing

experiences (Garris et al., 2002).

The game is intended for small groups to play in

order to emphasize a team-based approach, and to

draw on the range of student’s different areas of

knowledge and expertise.

Development of an effective, interactive game

required two phases. Phase I focused on the

characterization of educational objectives to ensure

that the game would sufficiently address

disciplinary content, provide for consequential

decision-making and enable students to learn through

success and failures. This phase consisted of

setting learning objectives, (disciplinary expertise

and necessary preparation required to play the

game), the target audience (identification of game

end-users), and characterization of the infectious

disease underlying the game. Phase II consisted of

determining the conceptual framework including the

game design, objectives, scenario design (setting,

context, roles and responsibilities of key

decision-makers), consequential decision-making and

learning uptake (identification of parameters for

success and failure, debriefing and learning

assessment). The scenario development design was

facilitated by a rigorous consultative process with

experts in infectious disease management, public

safety, computer software design, e-learning,

education curriculum design and/or effective

classroom teaching. As undergraduate students are

the end-users of this game, it will be essential to

incorporate student participation and feedback

during the design phases of the scenario.

Infectious Disease Agent

A critical first step in design development was to determine the nature

of the health emergency. To ensure an integrated

co-operative response from various sectors (health

care, government, public health agency), we selected

an infectious disease agent that could rapidly be

transmitted from person to person, with marked

symptoms and complications including mortality.

Literature reviews were conducted to identify the

most appropriate infectious disease agent and best

practices for diagnosis, treatment and public

response.

The biological agent responsible for our simulated infectious disease

outbreak is modeled after a norovirus. Norwalk-like

viruses or ‘nor viruses’ are a leading cause of

acute gastroenteritis epidemics in industrialized

countries (Moe, Christmas, Echols and Miller, 2001).

Norovirus outbreaks are characterized by symptoms of

severe vomiting, watery diarrhea, nausea, abdominal

cramps, fever and general malaise. Onset of symptoms

is generally 15-48 hours after exposure with illness

lasting 12-60 hours (Hutson, Atma and Estes, 2004).

Noroviruses are the cause of acute gastroenteritis

in people of all ages with documented transmission

following direct person-to-person contact,

consumption of contaminated food, namely raw

oysters, bakery products, fresh fruit and

vegetables, (Berg, Kohn, Farley and McFarland, 2000;

Long, Adak, O’Brien and Gillespie, 2002;) water

(ice, well or bottled water, and during swimming,

(Cannon et al., 1991; Pedalino et al., 2003;) and

following exposure to contaminated environmental

surfaces and to airborne droplets containing the

virus (Marks et al., 2003). Noroviruses are

transmitted very easily due in part to their low

infectious dose with less than 10 virions sufficient

to infect a healthy adult (Moe et al., 2004). In

our web game OUTBREAK!, contamination of a

fictitious brand of bottled spring water (Corneil’s

Best) with a variant strain of Norwalk virus was

selected as the source of the foodborne/waterborne

outbreak.

Learning Objectives and Pedogogical Approach

Learning objectives were identified in five major

categories (Table 1):

1. Observation and analysis: The first learning

objective requires users to analyze descriptive

health sciences scenarios, comprised of both text

and graphics. Information provided early in the

learning exercise must be retained for successful

problem assessment and derivation of solutions

throughout the game (Schank, Fano, Bell and Jona,

1993).

2. Knowledge application - Learning through failure

and success: Users must use knowledge acquired

through a wide range of courses to understand

scenario descriptions that include use of medical

terminology, scientific language and scientific

approaches (Schank et al., 1993).

3. Health science expertise - Problem-based

learning: As this scenario-based game was designed

for interdisciplinary health sciences programs, it

was essential for the game to provide a greater

understanding of health sciences theory and

approaches, particularly in the fields of anatomy,

physiology, epidemiology and public health. (Schank

et al.).

4. Risk communication- reflection opportunities: An

integral part of any organizational response to

public health crises is effective and timely risk

communication. Decisions regarding when to release

information on sensitive public health and safety

issues, how to select the individual delivering the

messages and when to involve the media are complex

and critical management skills that will be

addressed in the game design (Schank et al.).

5. Crisis-management, consequential decision-making,

goal based scenario: Consequences of decisions

regarding the triage of emergency room patients,

communications with public health authorities,

strategic deployment of emergency personnel and

resources will illustrate the complex and dynamic

interrelationships between emergency personnel,

their communications and access to specialized

equipment and protection (Schank et al.).

Table 1. Learning objectives and pedagogical

approach used to develop scenario-based game

design.

|

ormal" style="text-align:justify">

Pedagogical Approach

(Shank, 1993) |

|

Observation and analysis |

Assessment through replaying events |

|

Knowledge application |

Learning through failure and success |

|

Health sciences expertise |

Problem-based learning |

|

Risk communication |

Reflection opportunities |

|

Crisis management, consequential decision-making |

Goal based scenarios |

Game Objective

The objective of this public health scenario-based game, OUTBREAK!,

is to successfully mitigate and manage the

infectious disease outbreak. Containment of the

outbreak will be measured by the absence of new

cases of infection, and minimal number of

casualties. Effective management of the outbreak

will be measured by minimal disruption in the

operation of the game city services including

maintaining a strong economy, tourism and special

events.

Game Framework and Design

The fundamental objective of OUTBREAK! is to enable students to

make informed decisions within the context of an

infectious disease health emergency. Decisions will

be required at three levels or ‘lenses’: 1.

Municipal government, 2. Public health and 3.

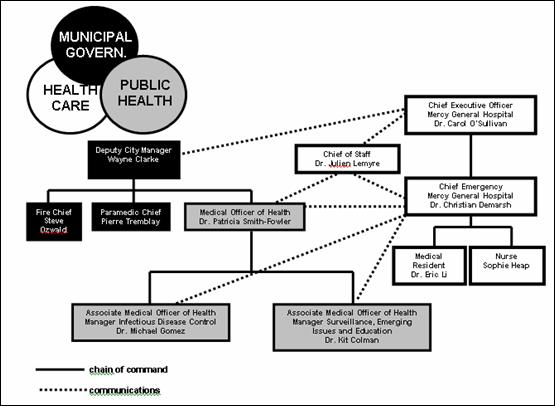

Health care (Figure 1). The game

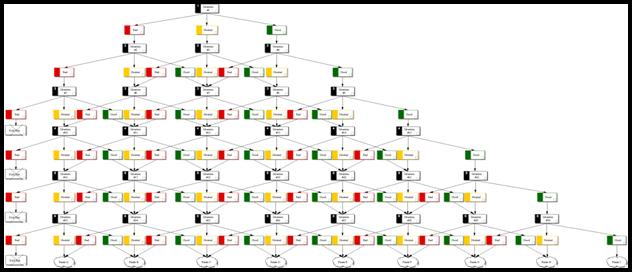

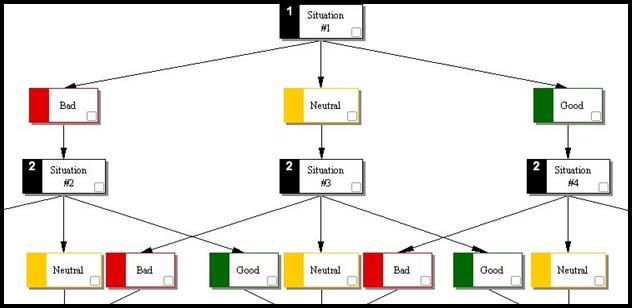

requires players to make a series of decisions based

on six situations that occur within the linear

timescale of an infectious disease outbreak (Figure

2). OUTBREAK! is divided into six levels,

each level requiring students to answer four

questions within one of the three lenses (municipal

government, public health, healthcare; Figure 1). By

dividing the game into different levels, players are

required to demonstrate a level of expertise within

each lens in order to progress to the next level.

This will further the educational objectives by

ensuring that all students gain exposure to each of

the three lenses.

A decision-matrix (Table 2) will be used

to stream students through to the next situation on

the subsequent level. For each situation, players

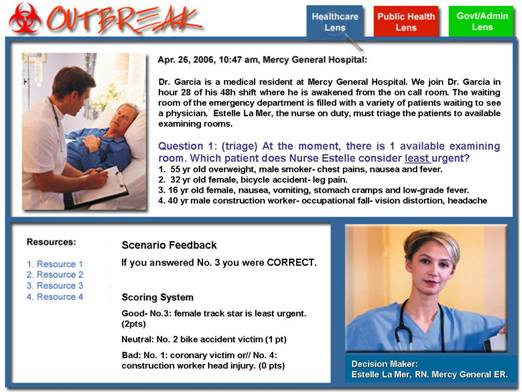

must make decisions for four scenarios. Each

scenario presents the players with four possible

options (Table 3) representing one Good decision,

two Neutral decisions and one Bad decision. Each

question will depict an event during the timeline of

an infectious disease outbreak (scenario). Scenarios

will be introduced in a Scenario Context page which

will provide the setting of the event, the

decision-maker’s profile and information necessary

to provide context to the event. Finally, a Scenario

Feedback page will provide the player with specific

feedback regarding the decision selected

(Figure 3). Players

that consistently select Good decisions are directed

through the decision tree thereby maximizing total

score (Figure 2). The rationale underlying this

strategy is twofold. First, pedagogically, it was

important to design a decision tree that would

enable players to overcome bad decisions by making

good decisions in subsequent situations. Second, as

individuals often make decisions that are not

intrinsically harmful or disadvantageous, it was

decided that 50% of the options would represent

neutral decisions. These neutral decisions would

require players to make sound decisions that would

fall within the limits of best practice. The

decision score matrix (Table 3) is used to determine

how each decision cluster (representing a single

level) contributes to the decision path for the next

scenario situation.

|

| |

Figure 1. Decision-Makers Map.

|

Figure 2A. Full decision making tree. See

Fig. 2B for details.

|

|

|

Figure 2B. Decision Tree details.

|

Figure 3. Scenario Design.

|

Table

2. Decision Score Matrix.

|

Choices |

Weighting |

Sample |

Score |

Feedback |

|

Decision 1A |

2 |

|

2 |

Good answer |

|

Decision 1B |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 1C |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 1D |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 2A |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 2B |

1 |

|

1 |

Neutral answer |

|

Decision 2C |

2 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 2D |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 3A |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 3B |

1 |

|

1 |

Neutral answer |

|

Decision 3C |

2 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 3D |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 4A |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 4B |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 4C |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Decision 4D |

2 |

|

2 |

Good answer |

Table 3. Pedagogical Impact of Decision Score

Matrix.

|

Decision 1 |

Decision 2 |

Decision 3 |

Decision 4 |

Sum (Score%) |

Path |

|

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

8 (100%) |

GOOD |

|

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

Neutral (1) |

7 (87.5%) |

GOOD |

|

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

6 (75%) |

GOOD |

|

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

Bad (0) |

6 (75%) |

GOOD |

|

Good (2) |

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

5 (62.5%) |

NEUTRAL |

|

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

Neutral (1) |

Bad (0) |

5 (62.5%) |

NEUTRAL |

|

Good (2) |

Good (2) |

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

4 (50%) |

NEUTRAL |

|

Good (2) |

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

Bad (0) |

4 (50%) |

NEUTRAL |

|

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

4 (50%) |

NEUTRAL |

|

Good (2) |

Neutral (1) |

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

3 (37.5%) |

NEUTRAL |

|

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

Bad (0) |

3 (37.5%) |

NEUTRAL |

|

Good (2) |

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

2 (25%) |

BAD |

|

Neutral (1) |

Neutral (1) |

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

2 (25%) |

BAD |

|

Neutral (1) |

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

1 (12.5%) |

BAD |

|

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

Bad (0) |

0 |

BAD |

Learning Assessment

By limiting the game design to pre-determined options, this educational

tool will emphasize decision-making approaches

guided by consequences, penalties and rewards. The

individual weighting of each decision ensures that

game remains strategic, with only 27% of possible

options leading to the Good Path, 47% options

leading to the Neutral Path and 27% options leading

to the Bad Path. The strategic weighting of each

decision ensures that approximately 73% of possible

answers will propel the student through the game. If

a student makes a series of consecutive Bad

decisions, the game is over (Figure 2).

Performance in the game will be measured through a morbidity/mortality

score, which will be correlated to a ‘public health

expert scale’ (Table 4) ascertained using a disease

algorithm based on the amount of time the user takes

to complete decisions. Time penalties will be

awarded when players make Bad or Neutral decisions.

Strategic application of time penalties may also be

imposed for decisions that are considered critical

for successful resolution of the outbreak.

Table 4. Performance: Level of Public Health

Expertise.

|

Level 1 |

Public Health Expert (case range x-xx) |

|

Level 2 |

Public Health Associate (case range xx-xxx) |

|

Level 3 |

Public Health Novice (case range xxx-xxxx) |

|

Level 4 |

The Contaminator (case range >xxxx) |

Conclusion

The potential for OUTBREAK! to contribute to public health

education and training is significant. The selection

of a waterborne illness as the infectious disease

agent engages Canadian students with the parallels

to the 2000 Walkerton,

Ontario outbreak, which produced serious illness in

an estimated 2,300 people following exposure to E.

coli O157:H7- contaminated drinking water (Schuster

et al., 2005

). Since waterborne disease agents are responsible for some

of the largest disease outbreaks and public health

emergencies, inquiries into the cause of these

outbreaks have led to changes in public policy, and

increased awareness of the importance of

interagency/intragovernmental communication and

cooperation. Hence, creating a game around the

premise of a waterborne infectious disease outbreak

complements traditional teaching methods in

emergency preparedness by

providing an excellent case study for students to

learn more about healthcare response, health policy,

and disease management in emergency situations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

We wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and the

journal editors for their excellent comments and

suggestions. We would like to recognize the

financial support from the Institute of Population

Health, and the Center for University Teaching at

the University of Ottawa for grants which permitted

the development of this game prototype. We also

thank several scientists at the Institute of

Population Health, including Wayne Corneil, Dr.

Carol Amaratunga and Dr. Louise Lemyre; the Center

for E-learning, TLSS, at the University of Ottawa,

including Richard Pinet, André Seguin, Rémi Rousseau

and Nicolas Hessler, and to our excellent student

research assistants, Hany Rizk, Naim R. El-Far, Alex

deMarsh and

Zainab Khan.

References

Berg, D.E., Kohn, M.A., Farley, T.A. & McFarland,

L.M. (2000).

Multi-state outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis traced to

fecal-contaminated oysters harvested in Louisiana.

Journal of Infectious Diseases. May;181 Suppl

2:S381-6. Review.

Cannon, R.O., Poliner, J.R., Hirschhorn, R.B., Rodeheaver, D.C.,

Silverman, P.R., Brown, E.A., Talbot, G.H., Stine,

S.E., Monroe, S.S. & Dennis, D.T. (1991). A

multistate outbreak of Norwalk virus gastroenteritis

associated with consumption of commercial ice.

Journal of Infectious Diseases, 164(5):860-3.

Garris,

R., Rober A.

&

James, E. D. (2002). Games, motivation and learning:

a research and practice model. Simulation

& Gaming,

Vol 33(4): 441-467.

Hutson, A.M., Atmar, R.L. & Estes, M.K. (2004). Norovirus disease:

changing epidemiology and host susceptibility

factors. Trends in Microbiology, Jun;12(6):279-87.

Long, S.M., Adak, G.K., O'Brien, S.J. & Gillespie, I.A. (2002). General

outbreaks of infectious intestinal disease linked

bottom:4.3pt;

margin-left:0in;text-align:justify">

Marks, P.J., Vipond, I.B., Regan, F.M., Wedgwood, K., Fey, R.E. & Caul,

E.O. (2003). A school outbreak of Norwalk-like

virus: evidence for airborne transmission.

Epidemiology and Infection, Aug;131(1):727-36.

Moe, C.L., Christmas, W.A., Echols, L.J. & Miller, S.E. (2001). Outbreaks

of acute gastroenteritis associated with

Norwalk-like viruses in campus settings. Journal

of American College Health, Sep;50(2):57-66.

Pedalino, B., Feely, E., McKeown, P., Foley, B., Smyth, B. & Moren, A.

(2003). An outbreak of Norwalk-like viral

gastroenteritis in holidaymakers travelling to

Andorra, January-February 2002. Euro

Surveillance. Jan;8(1):1-8.

Schank, R., Fano, A., Bell, B. & Jona, M.(1993). The design of goal-based

scenarios. Journal for the Learning Sciences,

3(4): 305-345.

Schuster, C. J., Ellis, A. G., Robertson, W. J.,

Charron, D. F., Aramini, J. J., Marshall, B. J. &

Medeiros, D.T. (2005). Infectious disease outbreaks

related to drinking water in Canada, 1974-2001.

Canadian Journal of Public Health, 96(4),

254-258.

|

|

|

|

|