Introduction: three worlds

During the past decade, a gap has appeared between

higher education and the rest of the digital world.

While academia has moved a great deal of content and

activity into course management systems, the World

Wide Web has developed a new architecture, usually

dubbed “Web 2.0.” Around this time computer gaming

has grown into a vital, global industry. Course

management system(s) (CMS) have supported a very

different world of computer-mediated communication,

and nearly a decade of institutional and individual

practice has deepened the difference. We argue that

CMS are going to make some efforts to cross that

chasm in the near future, but the overall gap is

likely to persist.

We

can glimpse the chasm’s current depths by outlining

these two recent cybercultural movements. First, at

this point in the World Wide Web’s existence, the

quantitative successes of Web 2.0 are well-known.

The blogosphere

continues to double in size, now aiming for

100 million active blogs. The wiki world booms,

from the rise of Google’s wiki platform (Google

Docs) to Wikipedia’s

Educational users of Web 2.0 have ridden this

overall growth wave. Teachers, students, and

support staff from K-16 have created content and

communities through blogs, wikis, podcasts, and many

other platforms. An edublogger community has

arisen. Scholarly articles and books about teaching

with Web 2.0 have seen print, while conference

presentations and online publications are

commonplace (Yancey 2004, Downes 2005). Pedagogical

forms have developed for years, from profcasting

(Campbell 2005, Educause Learning Initiative 2005)

to courseblogging, wiki-based or –inspired

collaborative writing (Lamb 2004, Benkler 2005) to

Latin wiki encyclopedias (Alexander 2006). For

examples one may consult one

listing at the Academic Commons, or

the Academic Blogs wiki. Public intellectuals

have used blogs and podcasts as media for

communicating with a world audience. For example,

the conservative political blog

Instapundit is one of the most widely read blogs

in the world, and authored by a law professor. Juan

Cole writes

Informed Comment as a Middle Eastern scholar

at the

University

of Michigan. .

Second, computer gaming has taken off in parallel

with Web 2.0. The gaming industry has been

comparable in size to the movie industry for several

years. Gaming platforms are diverse, including

laptops, handhelds (Xbox, Nintendo), mobile phones,

mobile devices (GameBoy, PlayStation Portable),

extended systems (Dance Dance Revolution), and newer

devices (Wii). Game genres have diversified, from

casual games to massively multiplayer online games (MMOs

or MMOGs), platform-jumpers to flight simulators

(Wolf 2002, Newman 2004). Game player demographics

have moved beyond the old stereotypes of teenage

boys. And game content is all over the map, from

war games to card games, literary games to religious

ones. That content is increasingly produced by

players, who report on their experiences, offer

suggestions for players and designers, create

fiction either by or using games themselves (Jenkins

2006).

As

with Web 2.0, gaming has been picked up by

education, most notably in the wake of James Paul

Gee’s landmark book (Gee 2003). Games have emerged

as learning objects, pedagogically aimed content

containers (Prensky 2001, Shaffer 2007). Educators

have taught with off-the-shelf games (for example,

Civilization), modifying or “modding” pre-existing

games (MIT’s

Revolution, or

the Arden project; see also the Arden’s project

lead’s

self-criticism). Educators also make games from

scratch (UNC’s Econ 201 game) (Bryant 2007). As

objects for research and curricula, games have been

the center of a new field, game studies, which now

features scholarly conferences and books (Brenna

2005, Dagger 2007). Moreover, following Gee’s lead,

educators have been considering what pedagogical

lessons can be learned by games and their successes

(Gee, n.d., Mayo 2005).

To

these two waves of extensive innovation, higher

education has largely been immune, at least in terms

of course management systems. The leading such

platforms – Blackboard and Blackboard-owned WebCT –

are clearly different creatures. They have nothing

to do with gaming, of course. They tend to have

(literally) radically different architectures, when

compared with Web 2.0 platforms. The latter are

deeply social platforms, while the former are

carefully restricted in population to a single class

(not course) population. Web 2.0 enjoys distributed

conversations, where ideas, commentary, and

controversy cut across numerous sites (multiple blog

posts and comments), or occur within them (wiki

pages). CMS, in contrast, block incoming traffic.

Even their look and feel is different, with

Blackboard’s interface resembling commercial

training platforms, such as IBM’s LearningSpace,

rather than the fluid microcontent arrays presented

by MySpace or Digg.

Is

it possible that CMS will become more like Web 2.0?

One way of answering that question is to examine how

CMS approach Web 2.0 in the present, and

extrapolating from that. A second way is to

consider the strengths of CMS for higher education,

and to see how they can be expanded to cover what

they currently miss.

Crossing the chasm

It

is difficult to separate most things within the

Web. Hyperlinking can connect objects, so long as

they are not protected by redirects. So while links

into a Blackboard class fail, resolving into that

campus’ gateway page, links out can hail the

strangest Web 2.0 content. To the extent that they

privilege document sharing (uploaded syllabi,

e-Reserves, uploaded readings) CMS deemphasize the

open Web, from an interface or user experience

angle. Yet from a deeper sense, nothing within CMS

architecture prevents an instructor from linking to

a blog post, or a student from adding a link to a

relevant Wikipedia entry from a discussion thread.

Similarly, very little blocks embedding YouTube or

other such media content, once all CMS support that

use of Javascript and DHTML-calling Flash files. In

this sense hyperlinks can cross the Web 2.0-CMS

divide with ease. It is not a matter for

technology, but individual practice. It is

possible, therefore, that the entire world of

CMS-housed classes will, in the near future, expand

their hypertextual outreach to Web 2.0.

There are also CMS versions of Web 2.0 platforms.

Blackboard and third-party developers have produced

wiki and blog plugins, as have members of the Moodle

development community. Given the open source nature

of

Sakai,

it is not unreasonable to expect similar additions

there. These silo Web 2.0 versions seem strange,

compared with that Web’s well-known openness. But

they do resonate with some forms of Web 2.0 in the

wild, such as LiveJournal blog posts and Flickr

images inaccessible to the world, save for a

white-listed audience. In fact most Web 2.0

platforms now offer different levels of privacy and

access, affordances which connect with the granular

permissions CMS developments seek. This

architectural connection may expand over time,

especially given the relative ease of developing

versions of applications already in widespread use,

and often in open source: tag clouds generators and

visualizations, RSS readers.

A

third level of CMS-Web 2.0 connection can be

glimpsed in recent experiments with what we can call

“extruded services.” These are tools by which CMS

users can publish microcontent to the open Web.

Perhaps the best example of such services is

Blackboard’s Scholar.com. This social bookmarking

site has much in common with older projects, such as

Del.icio.us (now owned by Yahoo), CiteULike, or

Connotea (Lomas 2005, Hammond,

Hannay,

Lund, Scott 2005). Users upload annotated links to

interesting resources, and can choose to make these

available to other users. What differentiates

Scholar.com from silo-ized wikis and blogs is that

users can extrude this content out of Blackboard and

into the entire Web. As with del.icio.us, one can

restrict access to some, none, or all of one’s

bookmarks. But one must be working from a

Blackboard campus to use this service. If

Scholar.com is deemed a success by Blackboard,

perhaps we shall see other “extruded” services, such

as platforms for blogging or podcasting out of the

campus-bound class space.

Discussing such bridges between CMS and Web 2.0 begs

a bigger question: why do institutions not simply

leave CMS behind and embrace this new Web? Assuming

rational choice as an explanation, we should

rehearse what institutions of higher education gain

from decidedly occupying one side of the chasm

between Web 2.0 and CMS.

To

begin with, it is clear that Moodle and Blackboard

afford easy entrance into the digital world for

large numbers of faculty. The relatively low bar of

entry needed to start up a CMS course – uploading a

single document, student population automatically

pre-populated – means that many more instructors

will move into that environment than would, say,

begin editing digital video, or creating

three-dimension content in even the easiest tools (Sketchup,

Second Life).

This represents a necessary first step for many

teachers, and can represent a major victory for

campus IT departments. Also appealing to the

faculty mind is that CMS are clearly academic

products. They are not repurposed social tools, but

clearly targeted applications aimed at specific

users. Their architecture suggests the physical

classroom, with its emphasis on a single section,

and the door closed to the world, as it were.

Additionally, CMS ease worries about copyright,

since by using them instructors can claim digital

fair use protection under

the TEACH Act. In essence TEACH allows

instructors to digitally reproduce old classroom

copyright tactics, such as wheeling in a VCR and

monitor to show a brief clip which noone else can

see. Lastly, the persistence of user interface

elements over time surely reassures users who might

be made nervous by Web 2.0’s frantic development

pace, where, as Tim O’Reilly teaches us, everything

is in beta (O’Reilly 2005).

From a campus IT perspective, leading CMS offer

still further advantages. A developer’s community is

present in both open source and commercial venues,

offering both new features which might be passed on

to users, and the opportunity to contribute.

Sticking with an already-established CMS avoids

potentially huge switching costs, even if prices

(license fees or coder salaries) go up, while

leveraging already sunk costs. Moreover, running a

local CMS instance allows a measure of local

control, not afforded by third-party hosts, be they

as durable-looking as Google or new as BigThink

The

previously-mentioned CMS-Web 2.0 bridges can realize

some of these virtues. For example, the popularity

of differential privacy settings could be considered

as good faith for TEACH-defended fair use. More

subtly, the continued growth of Web 2.0 means

faculty are increasingly familiar with its style and

strategies. Amazon.com, for example, uses tag

clouds and supports blogs. The growing numbers of

academic public intellectuals working by blog or

podcast means a growing familiarity with those

platforms on the part of their colleagues.

Similarly, discomfort reduction increases chances

for instructors to take advantage of Web 2.0’s very

CMS-like low bar to entry for making digital

content.

And

yet, until this chasm between CMS and Web 2.0 is

bridged, so much is lost. Digital content housed in

CMS never has a chance at reaching wider audiences

through Web 2.0’s network effects (think viral

videos, where viewership rockets up as people spread

news about them via words of mouth, or the influence

of leading bloggers). Nor can such content be

picked up later on through the “long tail” effect

(Anderson 2008). While faculty members may have

various good reasons for not wanting such global

audiences for their content, placing it in a silo

means that opportunity is foreclosed. The same is

true when content is not spidered by classic search

engines (Google, Yahoo), nor by emergent social

search services (Technorati, Google Blogsearch,

Podzinger).

The public sphere does not reap the benefit of

academic work in this way.

Pedagogical opportunities are also lost. For

example, users working through Web 2.0 content learn

strategies for following and participating in

distributed conversations. They might not be good

strategies, but everyone who has commented on

someone else’s Facebook or followed personal stories

through multiple LiveJournals has nonetheless

learned strategies for finding and assessing

information (Himmer 2004). Without participating in

that world, faculty and librarians cannot teach

better ways of navigating it. The large questions

of literacy in a participatory media age are

unaddressed when silos block that very

participation.

A

developmental separation also occurs. The frantic

pace of Web 2.0 service development means, among

other things, an innovation bounty. The sheer

number and diversity of projects is difficult to

keep up with, but provides a steady stream of

potentially useful tools, as even a casual glance at

the large volume of content in Emily Chung’s

eHub site or

TechCrunch. CMS development simply doesn’t keep

pace. Similarly the energetic development of data

mashups (Yee 2008) offers a variety of learning

opportunities, not to mention production

possibilities. Yes, students and instructors can

point to mashups from within a Moodle wiki, but they

cannot participate in making one from there, and

will work at one remove from that world so long as

they inhabit classic CMS. The more efforts made to

open out to Web 2.0 from CMS, the greater the

likelihood of mobilizing these energies.

Playing across another divide

We

can now return to the theme of gaming, and by means

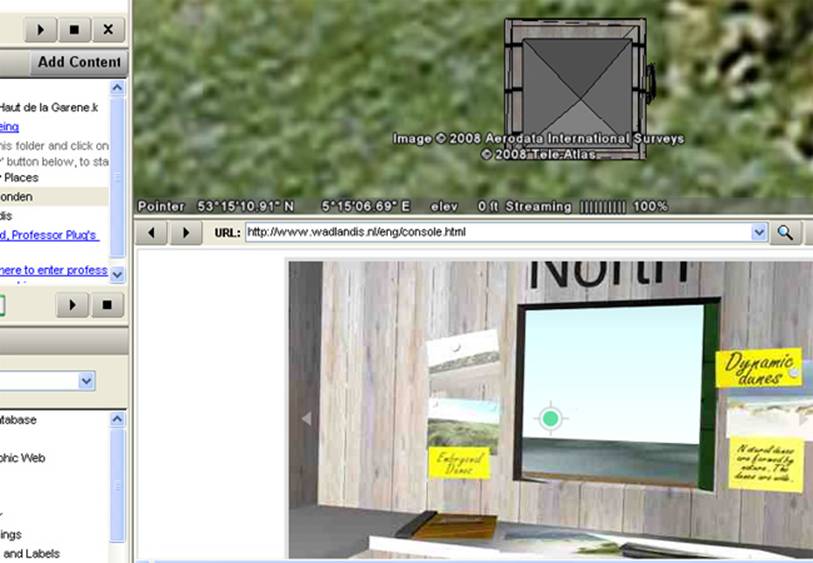

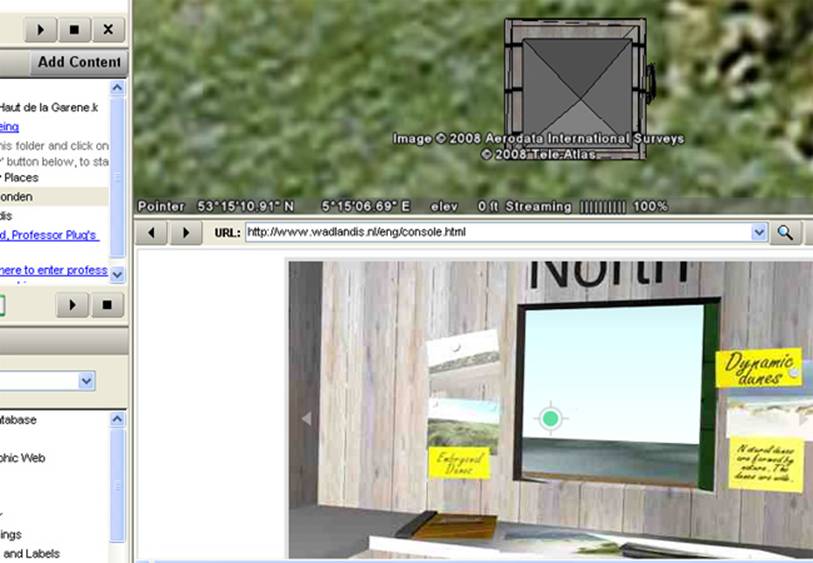

of an example. Consider the Dutch game,

Wadlandis.

Play concerns the search for one Professor Plug, an

environmental scientist working on mitigating global

warming, but mysteriously lost to the world (thanks

to Todd Bryant for the reference). Launched by the

Hier initiative, Wadlandis is a hybrid game. It

consists largely of browser-based content, but

viewable only through Google Earth. One navigates

between two windows, one spatial and the other

cartographic, trying to solve this mystery. …

On

the face of it this game is as far removed from the

CMS world as possible. It’s the product of an

interaction between a nonprofit and a giant

corporation, rather than academic content hosted by

a smaller software vendor. Content is accessible

to the entire world of PC users, and requires

literacy in gaming, which CMS do not make available,

nor teach. Despite featuring an academic character

and intellectual content, Wadlandis is not

associated with a class or campus. No institutional

registration is required (unless one counts running

Google Earth as a form of registration).

Wadlandis does illustrate neatly several points

about gaming in 2008, which brings it somewhat

closer to academe. First, the game’s existence

points to the diversity in game content – this is

hardly a first-person shooter. Indeed, it’s very

much a political game aimed at social activism.

This brings it into the domain of field of study,

and perhaps into the American tradition of campus

social engagement. Second, it is clearly a

pedagogical object. As James Paul Gee and others

point out, games teach their content and their

play. Wadlandis draws us in by stages of

instruction, much as a good instructor does. It

reinforces learned skills, and keeps bringing us to

the edge of Vygotsky’s competence zone. Third, the

game draws on a series of literacies, all of which

have been deemed of academic interest: map literacy,

information literacy (in the ALA sense), close

reading, and basic Earth science (Selfe and Hawisher

2007). In an exemplary way, Wadlandis therefore

points to connections between computer gaming and

higher education.

We

can bring gaming into the CMS world through our

earlier discussion about intersections between Web

2.0 and CMS. To begin with, note that the game is

open to the world. It exists in the wild Web, and

could be pointed to from within a Blackboard class,

perhaps identified by instructor as a learning

object. CMS-hosted content could not play a role

within such a game, given content restrictions. In

this respect games are removed from CMS, much like

Wikipedia or a CD-ROM. The strategies we’ve

outlined for crossing the gap between these worlds –

increased hyperlinking, internal versions of

external platforms, and extruded services – could

help connect CMS to gaming. Perhaps we should not

be surprised to see the release of a simple

game-authoring plug-in for Moodle. A method for

deploying games as e-Reserves within Blackboard is

probably more likely to arrive more quickly.

Figure 1. (http://www.wadlandis.nl/

in play, using Google Earth; screenshot by the

author)

At

a broader, more conceptual level, we can imagine

what CMS could learn from gaming. If games are

digital teaching objects, can we redesign course

management systems that draw on their pedagogy?

Bear in mind that games are increasingly social, not

so much player-versus-machine but player against

player (competitive), and players with players

(collaborative). Indeed, games are often

combinations of these three forms. Imagine, then,

at a basic level, a student being able to examine

another student’s or staff member’s profile to see

what skills they have attained (and chosen to

reveal), or what e-Reserves they’ve experienced.

Such a user might think of themselves competing with

classmates, in ancient academic style, or looking

for collaborators to boost their own learning.

Consider, too, the just-in-time teaching games

perform. Games often have tutorials, help files, or

hints available within the program. Such content is

also increasingly available on the Web. Could we

design a CMS which lets us experience learning

content apart from courses? Libraries, research

centers, writing centers, and other class-parallel

programs could provide some of this content, as

could digitized presentations from visiting speakers

or final class performances (recitals, films,

theses). Students, staff, and faculty could use

such a new CMS to find and access smaller content

chunks on demand. Making such content available in

new, cross-purpose ways might activate long tail

effects. It could also decouple learning from

courses. It is not a technological leap to conceive

of ready-to-launch cross-disciplinary tutorials

accessible to a general population, but a

philosophical one.

We

can take the gaming-CMS intersection still further.

At a strategic level, what does a campus CMS

implementation look like if we think of it as a

game? Could we envision massively multiplayer

Blackboard, with fluid interactions among “players”,

just in time learning, shared content creation, and

many different ongoing learning quests? In a real

sense campuses support all of these functions

already, but in other venues: offline, on off-campus

platforms, by informal learning, study groups, ad

hoc conversations. Insofar as CMS aim to be major

academic platforms for campus life, they could take

this approach to increase their utility and impact.

Put another way, how do we make the CMS-mediated

academic experience one to which learners return, as

they find games “sticky” or “addictive”? (Salen and

Zimmerman 2003, Koster 2004) We could be inspired

by the creation of the classic Web 2.0 project

Flickr, whose design emerged from a social game

(Graham 2006). Such a conceptual rethinking of the

CMS could very well lead to a very different

enterprise-level application.

Summary

Web

2.0 and gaming constitute different worlds apart

from CMS, based on very distinct information

architectures, cultures, expectations, and

practices. Connections with CMS are possible at the

object level: increased linking to Web 2.0 and

gaming content from within courseware, platforms

replicated with CMS, games as learning objects. At

another strategic level, the successes of Web 2.0

and gaming offer new ways of thinking about CMS as

social enterprises, playful areas, and more

effective venues for the productive intersection of

academia with technology.

References

Alexander, B. (2006) "Web 2.0: A New Wave of

Innovation for Teaching and Learning?". EDUCAUSE

Review, Volume 41, Number 2 (March/April 2006).

Retrieved March 2008 from

http://www.educause.edu/apps/er/erm06/erm0621.asp.

Anderson, C. (2008). The Long Tail. New York :

Hyperion.

Benkler, J. (2005). Common wisdom: Peer production

of educational materials. Presented at the September

2005 Advancing the Effectiveness and Sustainability

of Open Education Conference. Retrieved January 2008

from

http://www.lulu.com/content/162436.

Brenna, S. (2005) “Much Fun – For Credit.” The New

York Times, April 24, 2005. Retrieved February 2008

from

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/24/education/brenna24.html?_r=1&oref=slogin.

Bryant, T. (2007) “Games as an Ideal Learning

Environment”. NITLE Transformations, April 2007.

Retrieved February 2008 from

http://nitle.org/index.php/nitle/transformations/2007_4_13

Campbell, G. (2005) “There’s Something in the Air:

Podcasting in Education”. EDUCAUSE Review, Volume

40, Number 6 (November/December 2005). Retrieved

March 2008 from

http://www.educause.edu/apps/er/erm05/erm0561.asp.

Dagger, J. (2007) "The New Game Theory." Duke

Magazine, November-December 2007. Retrieved January

2008 from

http://dukemagazine.duke.edu/dukemag/cgi-bin/printout.pl?date=111207&article=game.

Dash, A. (2006). Scale social networks and

LiveJournal.com. IT Conversations podcast of

Meshforum 2006 presentation. Retrieved Janury 2008

from

http://www.itconversations.com/shows/detail1069.html

Downes, S. (2005) “E-learning 2.0.” eLearnMagazine,

October 17, 2005. Retrieved March 2007 from

http://www.elearnmag.org/subpage.cfm?section=articles&article=29-1.

Educause Learning Initiative (2005). “It’s Pod

Mania!” Educause Pocket Edition (November 2005).

Retrieved July 2007 from

http://connect.educause.edu/blog/dianao/it_s_pod_mania_educause_pocket_edition_2/1654.

Gee, J. (n.d.) “Learning About Learning from a Video

Game: Rise of Nations.” N.p., n.d. Retrieved

March 2008 from

http://simworkshops.stanford.edu/05_0125/reading_docs/Rise%20of%20Nations.pdf.

_____. (2003) What Video Games Have to Teach Us

About Learning and Literacy.

New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Graham, J. (2006). Flickr of idea on a gaming

project led to photo website. USA Today, February

27, 2006. Retrieved January 2008 from

http://www.usatoday.com/tech/products/2006-02-27-flickr_x.htm.

Hammond, T., Hannay, T., Lund, B., & Scott, J.

(2005). Social bookmarking tools: A general review.

D-Lib, April 2005. Retrieved January 2008 from

http://www.dlib.org/dlib/april05/hammond/04hammond.html.

Himmer, S. (2004) "The Labyrinth Unbound: Weblogs as

Literature." In Into the Blogosphere: Rhetoric,

Community, and Culture of Weblogs. Ed. Laura J.

Gurak, Smiljana Antonijevic, Laurie Johnson, Clancy

Ratliff, and Jessica Reyman.. Retrieved March 2008

from

http://blog.lib.umn.edu/blogosphere/labyrinth_unbound.html

Jenkins, H. (2006) Convergence Culture : Where Old

and New Media Collide.

New York :

New York

University Press.

Koster, R. (2004) A Theory of Fun for Game Design.

Scottsdale,

AZ: Paraglyph Press.

Lamb, B. (2004) “Wide Open Spaces: Wikis, Ready or

Not,” EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 39, no. 5

(September/October 2004): 36–48.

Lomas, C. (2005). Seven things you should know about

social bookmarking. Educause Learning Initiative,

May 2005. Retrieved Janaury 2008 from

http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ELI7001.pdf.

Mayo, M. (2005) "Ender's Game for Science and

Engineering: Games for Real, For Now, or We Lose the

Brain War. " Presentation to 2005 Serious Games

Summit.

http://www.seriousgamessummit.com/conference/speaker_presentations/Merrilea_Mayo.ppt

Newman, J. (2004) Videogames. London: Routledge.

O’Reilly, T. (2005) “What Is Web 2.0.” Article on

tim.oreilly.com. Retrieved March 2008 from

http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-Web-20.html.

Pew

Internet and American Life Project. (2005). Teen

content creators and consumers. November 2005.

Retrieved February 2008 from

http://www.pewinternet.org/PPF/r/166/report_display.asp

Prensky, M. (2001) Digital Game-Based Learning.

New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Salen, K. and Zimmerman, E. (2003) Rules of Play :

Game Design Fundamentals.

Cambridge,

Mass.:

MIT Press.

Selfe, C. and Hawisher, G., eds. (2007) Gaming Lives

in the Twenty-first Century: Literate Connections.

New York: Palgrave.

Shaffer, D. (2007) How Computer Games Help Children

Learn. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sifry, D. (2007) The State of the Live Web.

Retrieved March 2008 from

http://www.sifry.com/alerts/archives/000493.html.

See also

http://www.sifry.com/stateoftheliveWeb/.

Wolf, M. (2002) The Medium of the Video Game.

Austin:

University of Texas Press.

Yancey, K. B. (2004). Made not only in words:

Composition in a new key. CCC 56.2, 297-328.

Yee, R. (2008) Pro Web 2.0 Mashups: Remixing Data

and Web Services. Berkeley: APress.