Introduction

E-learning

activities and online learning environments are

increasingly widespread in UK Higher Education, not

for distance learning purposes, but for blended

integration with full and part time university

courses. Not all of these designs will be strictly

“hybrid” as discussed by Mossavar-Rahmani and

Larsen-Daugherty (2007) in that less than 50% of the

design will be online. This confronts Higher

Education teachers with many practical questions

about how learning and teaching should be

approached, what proportions of design should be

online, as well as the broader questions of the

meaning and practice of learning and teaching in the

twenty-first century, questions emphasized by Graham

in his first chapter of the popular Handbook of

Blended Learning (Bonk and Graham 2006). University

teaching has traditionally been based on

considerable interaction between learner and teacher

and among and between learners in seminars and

tutorials. This learning approach does not fit well

with the web-based training instruction model and

suggests that Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)

should look to the idea of “supported online

learning” when introducing online technologies into

the blend.

This paper gives a

sense of historical perspective to the development

of blended learning, by reporting on an

investigation into student “conceptions” of their

first experience of “blended learning”, during a

Higher Education Masters level module at a British

university.

Research approach and ideas

from the literature

Supported online

learning is learner and process focussed and

requires much student-student and student-tutor

interaction, mediated by the online environment.

According to a report commissioned by the UK

Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD):

“Supported online

learning involves significant interaction between

the learner and other learners as well as the tutor.

Typically this will include synchronous or

asynchronous conferencing, small group learning and,

possibly, face-to-face support in addition to online

access to materials and information.” (Reynolds,

Caley and Mason 2002).

In exploring how

to support online learning, it seemed sensible to

ask students about their perceptions of the blending

experience compared to face-to-face teaching, at a

time when most of their teaching was in traditional

mode, and the blend with online activities was a

fresh approach. It was important to find out how the

online activities in the blend would affect their

motivation to learn, in order to decide how best to

offer appropriate feedback and support through the

design of the online learning space. A review of

literature suggested that motivations for learning

were not permanent individual traits, but dynamic

aspects of student intentions in relation to

specific tasks in specific circumstances. This view

was built on constructivist foundations, where

students did not simply take in and store

information, but went on to make tentative

interpretations of experience, and test out those

interpretations (Kolb 1984; Perkins 1992; Race

1993).

Race’s model of

learning was similar to that of Kolb but added the

key idea of wanting and/or needing to learn as a

central drive throughout the learning process,

suggesting that if the want or need receded, the

learning was likely to do the same. Such ideas imply

a central role of motivation in the learning

process, suggesting that an understanding of student

motivation should enable more tailored and

appropriate support and intervention through the

learning and teaching strategy.

These ideas

moulded the development of the part-time

postgraduate module on which this study was based.

The module was designed to offer two face-to-face

sessions at the outset, followed by alternating

face-to-face and online sessions, with the latter

requiring asynchronous discussion of tasks and

challenges outlined in the “thought starter”

materials written specifically for this mode of

learning and teaching. The conceptions of blended

learning, identified through student interviews,

reflected students’ experience of such group

processes and online tools, which were intended to

encourage deep (Marton and Säljö 1976), or at least

strategic (Entwistle 2001), learning.

A small-scale

study was proposed which reflected the still

experimental nature of the blended mode in UK HE

provision, a factor which was leading business

students to choose traditional modes over blended

modes, on the basis of a “devil they knew”. Seven

students, who had just completed a postgraduate

study module delivered by a blend of online and

face-to-face teaching and activities, were

interviewed and verbatim interview transcripts were

analysed in detail using a phenomenographic method,

consistent with similar educational research to

identify “conceptions” as discussed by Brew (2001).

The research study did not attempt to fix ideas

about blended learning itself, but to identify

possible student conceptions of this learning

experience. Semi-structured interview questions

triggered discussions of feelings and experiences of

the blended mode. The questions also explored

conceptions at different phases of the course, by

relating first to students’ retrospective early

views of the blended mode, and then encouraging

students to discuss to what extent these views

remained constant throughout the module, and as far

as the period of the interview after the course.

This qualitative method was based on phenomenology

to uncover conceptions from the data, which were not

confined to discussing how an individual student

perceived learning, but how the blend of online and

face-to-face learning was perceived.

The author defines

“conception” as a mental construct formed by

combining all relating experiences, impressions and

notions. The interviewing of students after the

module was designed to find stable conceptions,

which were unlikely to be affected in their

expression by any tutor assessment power. The study

was influenced by a constructivist perspective

(Perkins 1992; Gold 2001), where students had

experienced a new method of learning and could be

expected to become actively engaged in trying to

make sense of the method.

It is normal in

phenomenographic method to avoid extensive

literature review before analysis of the data, in

order to prevent the literature outcomes influencing

the conceptions found in the data. Following several

trawls through the data to identify ideas associated

with blended learning, these ideas were developed

and grouped into conceptions, then tested against

three externally quoted frameworks found in the

literature, the first of these being student

learning approaches based on Marton and Säljö’s work

(1976) on deep and surface learning approaches and

extended by Entwistle (Table 1.1 p 19 1997) to

include strategic approaches. The deep approach here

embodies the students’ intention to understand ideas

for themselves (“transforming”). The surface

approach embodies the students’ intention to cope

with course requirements (“reproducing”). The

strategic approach embodies the students’ intention

to achieve the highest possible grades (“organising”).

The second

framework applied to the data in the study described

types of motivation derived from Entwistle (1987).

The conception themes derived from the study were

explored for association with type of motivation.

Entwistle distinguished between:

1. Competence motivation – a

search for successful learning experiences

2. Extrinsic motivation – a

search for qualifications or good grades

3. Intrinsic motivation – a

search for subject knowledge and understanding

4. Achievement motivation – a

search for improved self esteem through

achievement

To these positive descriptions he

adds the fear of failure, a negative, which is most

often seen as the downside of extrinsic motivation.

One of the ideas

emerging directly from the data was the clustering

of certain conceptions around the initial stage of

the module and the changing conceptions as learning

progressed. The data was therefore also compared to

the learning stages framework discussed by Perry

(1970) and later amended by Beaty and Morgan (1997).

Findings

The interview

transcripts yielded a total of 69 initial ideas, all

of which could be considered discrete. These ideas

were then grouped into nine themes or combinations

of experiences, impressions and notions relating to

students’ conceptions of blended learning.

1. Blended

learning is a positive conception. Positive

notions included varied advantages relating to the

blended teaching and learning approach, such as

working at the student’s own pace and access to

the web while online for regular scheduled

activity. This mode was also seen to represent

progress in learning: the new and different appeal

of the technology and mix of learning methods.

2. Blended

learning involves barriers. This conception

involved technology issues which caused students

difficulty such as ICT access problems,

unfamiliarity with the technology, potential

isolation during online weeks, lack of user

friendliness and possible cost issues regarding

internet connection time from a home computer.

3. Blended

learning involves competence. Conceptions of both

worry and pleasure over difficulty or challenge of

the blended mode were included here. Students were

focussed on the mode’s difference in approach from

traditional learning methods and whether they felt

it seemed to work or not.

4. Blended

learning requires confidence. This conception

included expressions of need for comfort and

confidence in learning, choosing familiar ground,

being prepared to be open in posting messages

online and working together in a safe and

supported situation with both face-to-face and

online support.

5. Blended

learning is particularly good for certain

subjects. This conception focuses on whether

blended learning approaches are context dependent.

6. Blended

learning needs a learning community. Considerable

references were made to the need for everyone’s

personal commitment to the delivery method to

support the group’s learning. Students in this

mode were more interdependent for their learning,

requiring interaction in learning, whether

face-to-face or online. There were also

expressions of regret that insufficient

interaction or commitment had been evident on this

module. Social benefit and team belonging were

important themes, and references were made to the

group behaving like a “learning set” (Revans

1982).

7. Blended

learning success depends on the personal learning

approach. The largest group of references related

to personal choice and preference being enabled

with blended learning. The blended mode gave

students the freedom to make time and quality

decisions about learning, about how much to do,

and whether a lazy, personal approach was made

easier to sustain through blended learning. The

conception also contained ideas of enjoyment,

self-discipline and adaptation to personal

learning style – in particular “reflector” or

“activist” styles (Kolb 1984).

8. Blended

learning requires self-direction. This group of

categories showed evidence of a clear awareness of

the need for self-directed learning with the

blended approach. Such self-direction was not

always achieved, in which case, there was an

expressed need for something to make people take

part – force or compulsion to make the effort,

sustained by stimulation and interest through

method and content or a strong commitment to

finding their own way to meaningful understanding.

9. Blended

learning requires a particular tutor role and

structure. This conception referred to a strongly

expressed view that small groups were an important

part of effective blended learning. It included

the idea that clear ground rules, whether imposed

by the tutor or the student team, were essential

and that ongoing support from the tutor, and

perhaps others, was part of the added value of the

experience of blended learning.

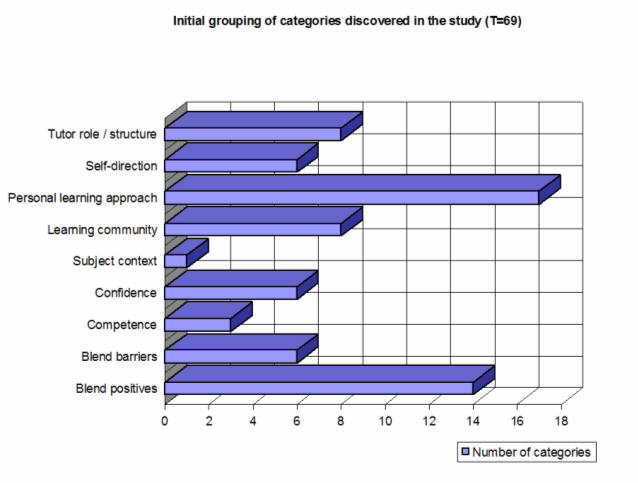

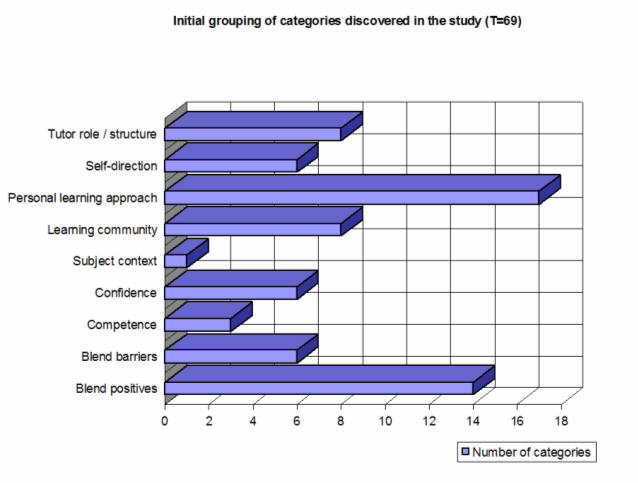

Figure 1 shows how

the different conceptions were supported by initial

categories in the data arising from the

phenomenographic analysis.

Figure 1. Initial

grouping of categories discovered in the study to

form conceptions

A broadly similar

profile relates the number of idea categories and

number of references to that category in each

conception, but relatively many more references were

found to personal learning approach, tutor role /

structure, learning community and self-direction.

Variations in

stage at which conceptions arise

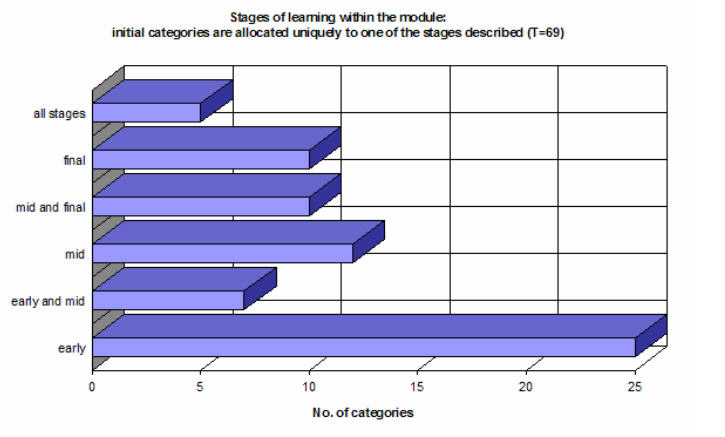

Specific

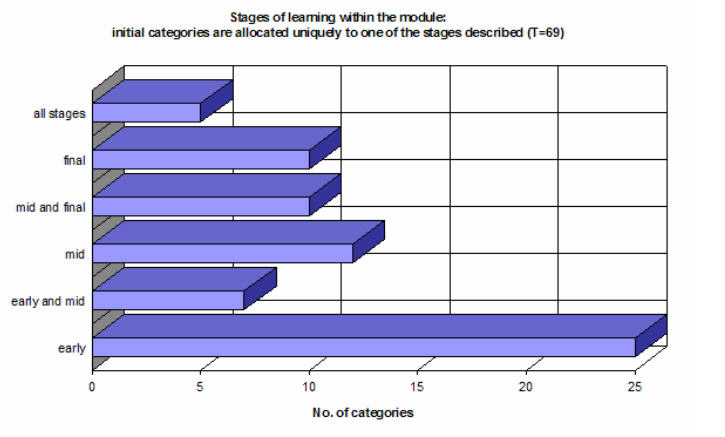

categories were seen to relate to different stages

of the learning within the module. Each category was

placed alongside a stage on the basis of the context

as well as the content of the category. While the

stages were allocated subjectively, the context of

the references helped to validate the choice. Figure

2 gives a clear picture of the predominance of

conceptions relating to the early stage, during

which students are coming to terms with a new method

of teaching and learning.

Figure 2. Stages of Learning within

the module: initial categories are allocated

uniquely to one of the stages described

Early stage

categories centred around technology difficulties,

concerns over personal competence and confidence,

tutor role and support and structure provided by the

tutor, including references to a teaching model,

also a conception of being different and special,

undertaking risk. Categories relating to a final

stage of learning (based on transcript context and

position) included regret in hindsight at not using

opportunities recognised in blended learning, a view

that blended learning was the future of learning,

unexpected benefits and recognition of wider

learning arising from the blended approach, an

awareness of growth and personal development through

self direction. Categories arising throughout the

stages included ideas around speed of access, logic

and structure, tutor facilitation, appropriateness

for subject and an easy mode to choose in order to

do a minimum amount of work.

Variations in

student learning approach

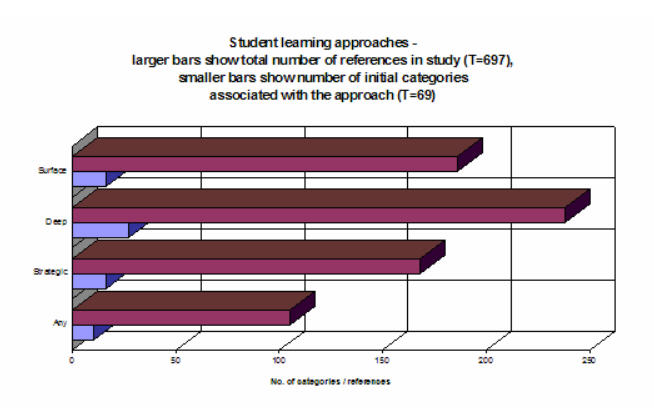

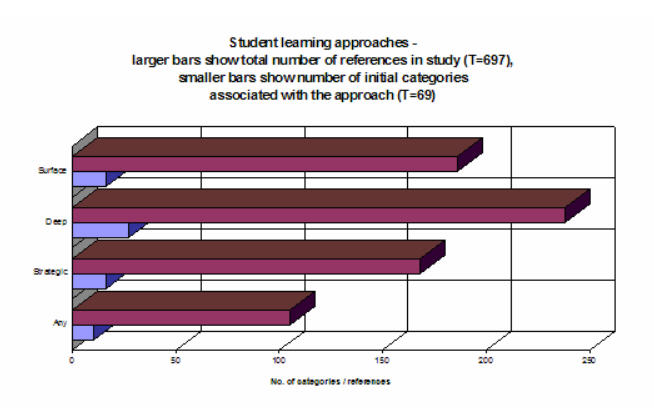

By applying the

deep, surface and strategic student learning

approaches to the initial categories in the data,

Figure 3 was produced. Deep learning and strategic

learning approaches together outnumbered surface

learning approaches in the data. Surface approaches

were associated with making it easy to get out of

class, a need for comfort and confidence in

learning, requiring force or compulsion to

earn, a self-confessed lazy approach

to learning, the wish for a right or correct way of

doing things, various blend “barriers” and the need

for familiar ground.

Figure 3. Student learning approaches in this study

Strategic

approaches related to a recognised learning style

and deliberate strategy for learning, and

self-directed learning; also finding value in a

smaller group and team belonging to share

information and using words such as “useful” and

“value” in relation to blended learning.

Deep approaches

related to ideas such as surprise or unexpected

learning, thinking and reflecting, trust and

openness in the team room (asynchronous text-based

medium), difficulty and challenge, a need for

commitment from the group to make blended learning

work, personal achievement, changed behaviour as a

result of the experience, the difference in the

learning approach in this module, enjoyment,

freedom, healthy growth and development and

interaction in learning.

Variations in

types of motivation

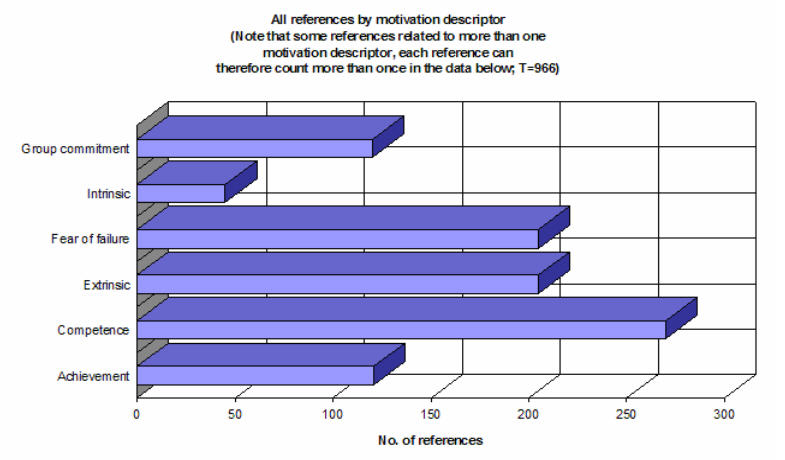

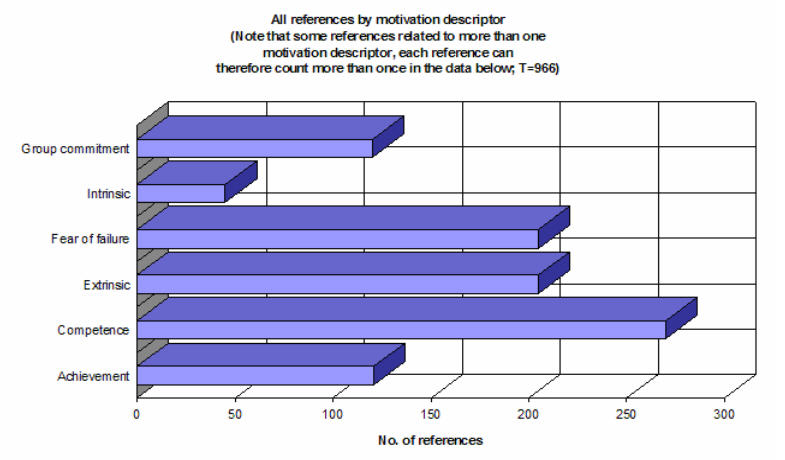

The motivation

descriptors of “competence”, “extrinsic”,

“intrinsic”, “fear of failure” and “achievement”

were applied to the data on initial categories. It

proved difficult to identify just one descriptor for

every category so 25 of the categories were assigned

more than one descriptor. Even then, there seemed to

be gaps where the existing motivation descriptors

did not relate to the categories. A possible further

descriptor of “group commitment” was added to the

framework which then accounted for the gaps. “Group

commitment” motivation could be understood here to

mean seeking to avoid the worry of letting others

down, pulling one’s weight in the team, wishing to

help others to learn for mutual benefit, feeling one

has to put in effort for the team’s sake or that of

other specific members of the team. Supporting the

development of this kind of group growth features

largely in Janet MacDonald’s advice on developing

online learning (2006) and is a driver for

e-moderating advocated by Gilly Salmon (2000).

Once this

additional descriptor was introduced, it was

possible to assign categories to the descriptors,

which added considerably to the understanding of the

data. Figure 4 shows how references were grouped

according to motivation descriptor.

Figure 4. All references by

motivation descriptor

The relatively small number of references to

intrinsic motivation could probably be explained by

the focus on the process of blended learning, rather

than the module content in this study.

Stages of learning

One of the

features of the study was that while useful

conceptions of blended learning were identified,

there seemed to be no hierarchy relating the

conceptions in any order of precedence. The data did

not suggest that some conceptions related to a

deeper level of learning for individual students in

the sample; rather they suggested that student

conceptions of the phenomenon studied changed with

the progress of the learning experience.

Some of the

conceptions arising from the study were relevant to

student experience right through the module (blend

positives, subject context appropriateness, personal

approaches to learning and self-direction); but

other conceptions related clearly to one or more

stages in the process. So conceptions of blend

barriers related only to the early stage, competence

issues arose in the first half of the module until

fears are allayed by feedback and /or increasing

confidence, possibilities of a learning community

arose mid way and developed through the rest of the

module and issues relating to a desire for tutor

control and structure related principally to the

initial phase of the module.

Other writers who

have referred to learning stages include Perry,

(1970) and Beaty and Morgan (1997). Perry described

an initial stage of unitarist, right/wrong learning

which seems to fit with the prevalence of references

in this study to blend positives or negatives

(barriers). Issues of competence and lack of

confidence, together with a dependence on the tutor

role and clear structures within the student

conceptions would support Perry’s thesis. In his

discussion of the development of students through a

college experience (1970), Perry demonstrates how

most students moved through uncomfortable stages

from this initial unitarist view, which accepted an

absolute teacher authority, through perceptions of

diversity of opinion and uncertainty despite the

continued need to find the “right” answer,

ultimately reaching a relativistic world in which he

or she might commit personally to an intellectual

maturity, admitting uncertainty and pluralism as the

norm. Perry stressed the courage required to move

through these stages of development and the need for

increased support from the tutor to allow this

progression.

Similar ideas were

developed in “In the World of the Learner”, a

chapter in Marton, Hounsell and Entwistle’s The

Experience of Learning (1997), where Beaty and

Morgan also set out stages of learner development

(p134). Fresher, Novice and Intermediate stages all

saw the system and the institution in control of

learning, while the Expert stage involved control by

self within a course and the Graduate stage involved

control by self both in content and method of

learning. These ideas relate to those suggested by

this research study as all describe a process of

moving towards self-direction and personal

responsibility for learning with early stages which

require considerable support and offer opportunities

to take it easy or drop out.

These outcomes fit

with ideas about the importance of initial support

and guidance and the tutor’s support role in blended

learning. Carl Rogers proposed the vital impact of

the tutor’s role at the start of the learning

process to develop student self-confidence and

provide meaningful but highly supportive feedback

and encouragement (1969). This critical tutor role

was emphasized in e-learning by Gilly Salmon in the

early steps of her e-moderating model (2000) and

developed by Garrison, Anderson and Archer as

teacher presence in their Community of Inquiry model

(2003). Teachers designing and delivering blended

learning need to devote considerable time to initial

reassurance (delivered both online and face-to-face)

as learners become accustomed to new strategies.

Approaches to

learning

As mentioned by

Laurillard (1984), there is a significant task

effect on choice of learning approach, that is

whether a surface, deep or strategic approach is

taken. Tasks identified within the module, the

teaching style and the ground rules of the module

itself, should take this conception of personal

choice into account and offer tools and tasks which

stimulate and deepen the learner’s approach.

Marton’s seminal

work on deep and surface learning, quoted in the

previous section, and its development by Entwistle

to include strategic approaches, is clearly

appropriate to the students’ conceptions of blended

learning in this study. The previous section set out

how surface learning approaches produced the least

important group numerically when related to

reference categories, and these tended to cluster in

the early stage of the module. The pedagogic design

of such blended modules must clarify to students the

benefits and characteristics of deep learning, both

to improve learning outcomes and to prevent the

level of regret in hindsight as late developing

students realise too late the opportunities for

self-direction and interaction which were available,

but which they may not have used to best effect.

However, much work is needed on how this might be

done, since it is possible for students to be led

into reproducing and organising behaviours, which

are intended to demonstrate deep learning, rather

than actually experiencing such transformative

learning.

According to Carl

Rogers “..any significant learning involves a

certain amount of pain..” (1969). The study showed

that the technology involved in online learning,

whether or not it was part of a blend with

face-to-face methods, would always present barriers

and problems to learners and teachers alike. Yet

committed learners, deep learners and strategic

learners would find a way around these problems in

pursuit of their learning objectives. Even surface

learners could be pulled through the barriers

through the motivation of responsibility to the

group.

The challenge to

the tutor wishing to use blended learning in HE is

to maintain encouragement and support throughout the

process (an early stage set of conceptions) and, if

necessary, take a creative route or a traditional

back-up route to ensure no student is seriously

disadvantaged by technology incompatibility or

breakdown. Endless enthusiasm for the technologies

and their possibilities for teaching and learning

can easily become technological determinism, where

the technology drives the teaching agenda instead of

the other way around. Morgan et al (2002) advise

“technological opportunism” to the tutor, to adopt

new ideas and experiment, but not on too many

dimensions at once – building experimental

technological elements on a sound base of proven

pedagogy . These technologies, although much

developed since this research study, continue to be

in a state of transition, and teachers need to offer

support to students who, like academics, are

grappling with steep learning challenges in ICT.

Motivation for

learning

The students in

this study appeared to need high levels of

enthusiasm and varying levels of support and

structure or rules to develop their motivation

levels at the outset of the module, probably because

it was situated in the second semester of the final

year of study, by which time natural curiosity had

long been exhausted for all but the most determined

of learners. Students also needed to be encouraged

to develop the confidence to experiment with the

tools of learning offered on a blended approach.

The proposition of

an additional motivator, that of group commitment,

where blended learning is organised to develop a

collaborative approach, was evident in this study

long before social software began to overtake

students’ personal and social lives, and may be

helpful in understanding the students’ conceptions

of what makes them put in some effort. Learning

motivation is clearly a highly variable and perhaps

elusive factor, which will always be mediated by the

student’s past learning experiences and their

current personal and, for working students, their

current work contexts.

Group commitment

While the notion

of group commitment is superficially evident in any

small student group which has developed a sense of

team, this study has demonstrated its explicit place

among conceptions of blended learning. Alongside the

other powerful motivations for learning identified

by Entwistle, group commitment is seen by some

students as a pre-requisite for online interaction,

perhaps more so than in a traditional face-to-face

delivery mode. The blended approach of the module

studied made online interaction through discussion

boards, rotas for posting messages and group

collection of data and problem solution a key part

of the module’s teaching and learning strategy.

These elements moved the online dimension of the

module from a passive support mechanism and data

storage tool to an additional source of learning and

a driver for reading and preparation of work.

The blended mode

can help to maintain motivation once the early stage

has been completed, by offering more opportunities

to develop a learning community online, bringing its

own group commitment and self-directed learning

rewards to those who commit to participating in

online discussion boards and intensive face-to-face

workshops. From the evidence of the transcripts, the

face-to-face sessions in a blended approach take on

an increased supportive and motivational role due to

their lower frequency and the perceived risk of

blended learning.

Conclusions

The study has

offered insights into student conceptions of blended

learning when this phenomenon was new to them. The

stages of learning associated with different

categories and conceptions offer teachers some ideas

for the development of their role in blended

learning, a role which clearly must be higher

profile at the outset of such a module, until

student-student interaction has reached a critical

mass and a learning community begins to develop.

Discussions of student motivation and learning

approaches have been related to the students’

conceptions and led to proposals concerning teaching

design strategies relating to the different stages

of the module. An additional motivator, group

commitment, has been proposed which is experienced

by students as a driver for learning.

What does the

study tell us about student conceptions of blended

learning? That students, who have experienced

blended delivery, valued the flexibility and

connectivity which encourages regular online forays

into wider resources and problems than those

confined to the classroom. The barriers posed by low

skill or technical access and cost tended to be

associated with an early stage of study and for many

were relatively easy to jump. Learning support and

skill development must remain key elements of an

introduction to blended learning.

Self-directed

learning strategies and the interdependence of the

student group were key factors in successful blended

learning for students. Not every student will be

prepared for this, and teaching strategies need to

provide support for students whose self-directed

learning skills are low, who are still at the

earliest stages of learning, and who do not feel any

commitment to the learning group. Rota strategies

and incentives to contribute jointly (prizes or

joint assessment for example) may be a way forward

here.

The small group

size preference for online activities, such as

themed discussion, was clearly a majority view and

was shown to engage potential lurkers and those who

do not contribute actively to class discussion. This

small group size was complemented by a teaching

strategy which actively moderated online discussion

with encouragement and support for effective

contribution, particularly in the early stages.

It was also

possible to say that confidence and developing

competence were associated with the early stages of

adopting a new learning strategy such as blended

learning, but that these concerns seemed to be less

evident as learning progressed.

This study was

conducted with a small group of students, and hence

cannot produce readily generalisable conclusions.

Its purpose was to discover conceptions of blended

learning for students new to this mode of delivery,

in order to point the way to further research which

might test these ideas and investigate further how

students could best be introduced to blended

learning. The next series of questions to be asked

about blended learning must include an investigation

into the conception of learning community and the

associated issue of “group commitment”. In what

contexts is this a motivator for students using

blended teaching activities? To what extent could

students be prepared for the group commitment

required, and how? Given the skills and attitudes

which seem to be seen by the students as necessary

for blended learning, what initial assessment might

be indicated prior to such study, to allow those

with skills needs or attitude mismatches to be

supported through the blended learning process? Is

it desirable and possible to develop a “readiness

for blended learning” instrument, possibly along the

same lines as the established “Self Directed

Learning Readiness Scale” created by Dr L

Guglielmino (1978)?

There are many

more questions to be answered. In particular,

whether the HE context of this study and much of the

research preclude its conclusions from application

to e-learning in the workplace; how best to develop

teaching and learning strategies which account for

dynamic motivational changes and learning approach

choices; and how best to identify students’

attitudes to, and skills for, blended learning, as

they start such modes of learning, so that teaching

and learning strategies can be adapted to their

background, prior experience and current and future

needs.

References

Beaty, L. and Morgan, A. (1997) 'The

World of the Learner', in Marton, F., Hounsell, D.

J. and Entwistle, N. (ed.), The Experience of

Learning; Implications for Teaching and Studying in

Higher Education. Scottish Academic Press:

Edinburgh.

Bonk, C.J. and Graham, C.R. (2006)

The Handbook of Blended Learning: Global

Perspectives, Local Designs. Pfeiffer.

Brew, A. (2001) 'Conceptions of

research: a phenomenographic study', Studies in

Higher Education, 26, (3), 271-285

Entwhistle, N. (1987) 'Motivation to

learn: conceptions and practicalities', British

Journal of Educational Studies, XXV, 129-148

Entwistle, N. (1997) 'Contrasting

Perspectives on Learning', in Marton, F., Hounsell,

D. and Entwistle, N. (ed.), The experience of

learning; Implications for Teaching and Studying in

Higher Education. Scottish Academic Press:

Edinburgh, Chapter 1.

Entwistle, N. (2001) 'Styles of

learning and approaches to studying in higher

education', Kybernetes, 30, (5/6), 593-602

Garrison, D.R., Anderson, T. and

Archer, W. (2003) 'Critical Inquiry in a text-based

environment: computer conferencing in Higher

Education', The Internet and Higher Education, 2,

(2-3), 87-105. [Online]. Available at:

http://communitiesofinquiry.com/documents/CTinTextEnvFinal.pdf

(Accessed: 26/10/06).

Gold, D.S. (2001) 'A constructivist

approach to online training for online teachers',

JALN, 5, (1), 35-57

Guglielmino, L.M. (1978) 'Development

of the Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale.'

Dissertation Abstracts International, 38, (646A),

Kolb, D. (1984) Experiential Learning

as the Source of Learning and Development.

Prentice-Hall: New Jersey.

Laurillard, D. (1984) 'Styles and

Approaches in Problem-Solving', in Marton, F.,

Hounsell, D. and Entwistle, N. (ed.), The Experience

of Learning; Implications for Teaching and Studying

in Higher Education. Scottish Academic Press:

Edinburgh, Chapter 8.

Macdonald, J. (2006) Blended learning

and online tutoring. Gower: Hampshire, UK.

Marton, F., Hounsell, D. and

Entwhistle, N. (eds.) (1997) The Experience of

Learning; Implications for Teaching and Studying in

Higher Education. Scottish Academic Press:

Edinburgh.

Marton, F. and Säljö, R. (1976) 'On

qualitative differences in learning. I - outcome and

process', British Journal of Educational Psychology,

46, 4-11

Morgan, W., Russell, A.L. and Ryan,

M. (2002) 'Informed Opportunism: teaching for

learning in uncertain contexts of distributed

learning', in Lea, M. R. and Nicoll, K. (ed.),

Distributed Learning; Social and cultural approaches

to practice. Open University Press, Chapter 2.

Mossavar-Rahmani, F. and

Larson-Daugherty, C. (2007) 'Supporting the Hybrid

Learning Model: A New Proposition', Journal of

Online Learning and Teaching, 3, (1).

Perkins, D. (1992) 'Technology meets

constructivism: do they make a marriage?' in Duffy,

T. and Jonassen, D. (ed.), Constructivism and the

technology of instruction. Lawrence Erlbaum, 45-56.

Perry, W.J., Jnr. (1970) 'Forms of

Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College

Years: A Scheme', in Entwistle, N. and Hounsell, D.

J. (ed.), How Students Learn: Readings in Higher

Education, 1. Vol. 1975 Institute for Research and

Development in Post-Compulsory Education, University

of Lancaster.

Race, P. (1993) The Open Learning

Handbook. Kogan Page: London.

Revans, R. (1982) The Origins and

Growth of Action Learning. Chartwell-Bratt: London.

Reynolds, J., Caley, L. and Mason, R.

(2002) How do people learn? University of Cambridge

Programme for Industry for CIPD Rogers, C. (1969)

Freedom to Learn. Merrill: Columbus, Ohio.

Salmon, G. (2000) E-moderating: The

Key to Teaching and Learning Online. Kogan Page:

London.