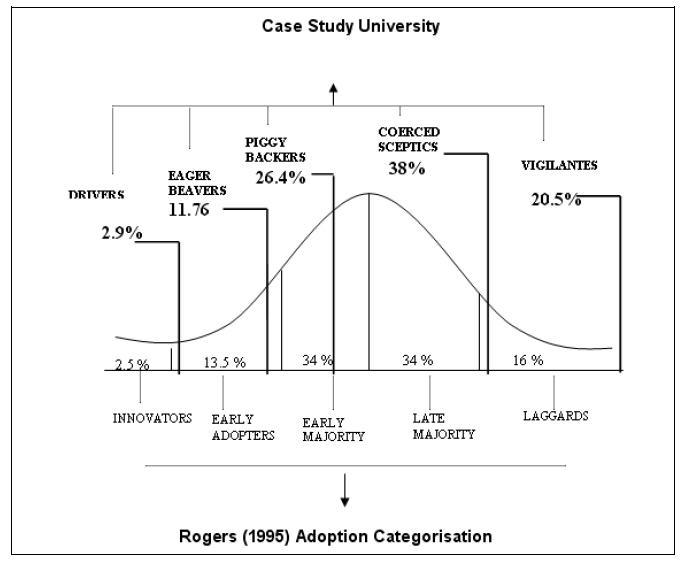

Figure 2: Comparison of WebCT user categories with

Rogers (1995) adoption model

User Segment 1 - Drivers

The drivers of WebCT were enthusiastic about the

technical capabilities of the system, possessed

advanced technical knowledge and had research

backgrounds within the area of online learning. They

adopted the technology during the pilot stage of the

implementation of WebCT. Drivers play a fundamental

role in the subsequent take-up of WebCT by other

faculty. As such, they play a pivotal role in

making the attributes of the technology transparent

to others.

User Segment 2 - Eager Beavers

The eager beaver group was willing to take the time

to explore the capabilities of the technology and to

experiment with the various tools and features. The

outcome of this experimentation determined the level

of their subsequent use of WebCT. A striking feature

of the eager beaver group was their research

background and area of expertise were not IT

related, but they were nevertheless interested in

exploring the potential of the technology. The group

explored the diverse capabilities of the technology,

experimenting with the assignment submission tool,

multiple choice question tools and communication

tools (discussion boards, chat rooms and email).

User Segment 3 - Piggy Backers

The piggy backers were reluctant to experiment with

the advanced tools and mainly used WebCT as a

document repository and notice board after

encouragement from their peers who had adopted the

technology earlier. However, a number of faculty

members commented that although they were willing to

explore the potential of WebCT, they decided not to

adopt because they were sharing a module with a

colleague that was unwilling to contribute.

User Segment 4 - Coerced Sceptics

This group adopted the technology when all existing

online learning systems became obsolete and hence

they were effectively forced to do so. They

approached innovation with a certain level of

trepidation, and peer pressure was often a key

factor in driving adoption. The coerced sceptics

were reluctant to experiment with the advanced tools

and mainly used WebCT as a document repository and

notice board. They lacked confidence and questioned

their technical ability to use the advanced tools of

WebCT. The coerced sceptics were reluctant to

continuously ask for support because they feared

being labeled incompetent.

User Segment 5 - Vigilantes

As with Roger’s (1995) categorisation of laggards,

the vigilantes were sceptical of the underlying

motivations and wider social implications of using

WebCT. This was because they believed the technology

had the potential to change the culture of academia.

In particular, they felt that online learning

represented the antithesis of the culture and values

of a UK university as the following quote

illustrates:

“I’m not a technophobe but I will still not use

WebCT because the technology goes against what we as

lecturers are here to facilitate.”

(Lecturer)

This interesting finding highlights the importance

of communication and deliberation between all

stakeholder groups about the wider impact of online

learning technology across higher education. The

vigilantes were not resistant to innovation per se,

but peer and institutional pressure was insufficient

to alleviate their broader concerns about the role

of online learning. Further, the findings also

indicate that reaching a point of mainstream

acceptance of the technology still did not influence

the vigilantes to adopt.

DISCUSSION

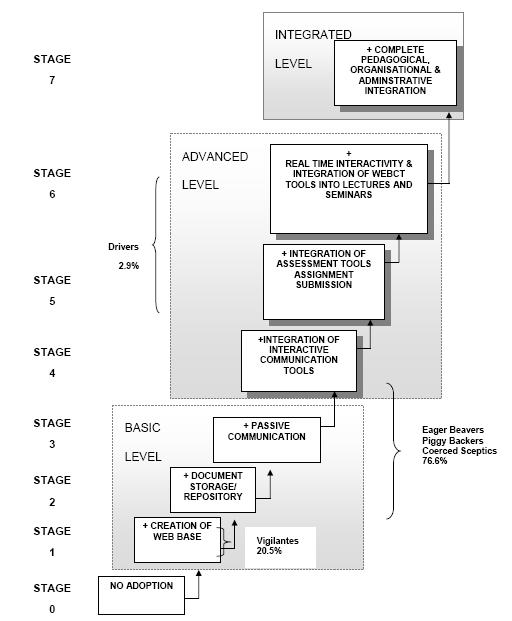

The findings show that the majority of faculty (76.6

percent) adopted WebCT, indicating that a ‘critical

mass’ of users has been achieved. Nevertheless,

most of this use is occurring at a very basic level,

between stages 1 and 3 which hardly constitutes a

radical change in user practices. Only 2.9 percent

of faculty used WebCT at an advanced level (stages 4

– 6), despite a large number being highly IT

literate and/or with a research interest in online

learning technology. (At the time of carrying out the empirical

investigation, there was no use of WebCT at a fully

integrated level (stage 7) because the system had

yet to be fully integrated with other functions and

departments across the University) The results

therefore indicate that critical mass alone can be a

misleading indicator of the sustainability of a new

technology as it fails to identify and deal with the

varied degrees of technological use observed in

practice. An innovation cannot be regarded as

self-sustaining simply because it has attained a

critical number of users. This finding is consistent

with the earlier work carried out by Geoghegan

(1994) who argued that critical mass alone is

insufficient to sustain the diffusion of technology

to a mainstream group of users. It should be noted

that faculty load and resistance issues may have

contributed towards the level at which WebCT was

used. However, it was beyond the scope of this study

to explore these variables. This is something that

will be explored in future studies.

The research findings also revealed that the

majority of faculty believed they did not receive

adequate information about WebCT. A number of

faculty members mentioned that their first exposure

to WebCT was at a departmental seminar presented by

the authors of this article. This highlights

an issue with the way that information about the new

system was communicated to faculty, whilst alerting

us to the importance of how the technology is

marketed, something which has not been identified in

earlier research and requires further investigation.

A recurring theme from the interviews was faculty

felt the earlier Intranet system made obsolete by

WebCT was adequate for their purposes, namely a

repository for lecture notes and an electronic

environment where notices could be passively

communicated to students. The majority of faculty

questioned the benefits of using WebCT, believing it

to be more complex to use than the basic Intranet

system it had replaced. One interviewee suggested:

“I’d found it [WebCT] hard to learn and it’s very

complex. It’s very involved putting files up. You

need something like 20 keystrokes in order to put

any file up, and that must be about 19 keystrokes

more than you need to do on the Intranet. It does

take longer to put things on.” (Lecturer)

WebCT training opportunities were made available but

the take-up was low. Faculty members believed they

had no reason to at that stage and were perfectly

content using the existing basic Intranet system,

but once the Intranet became obsolete, users had to

switch to WebCT. This indicates that the decision of

the majority of faculty to implement WebCT was

postponed until the last possible moment, i.e. when

it was actually enforced because the earlier system

was withdrawn. This key finding suggests that

although training is an important component to

facilitate the adoption of technology as also

identified by Green (2003) and Jacobsen (2000),

providing training does not necessarily guarantee

that these opportunities will be embraced and that

perhaps a more tailored type of training and support

based on individual needs is more appropriate. This

will be discussed further in the recommendations.

Interpersonal networks constituted the most

influential medium through which faculty

communicated their opinions of WebCT to one another.

This was despite other more formal channels such as

email and flyers, regularly informing faculty

members of the WebCT opportunities available to

them. Many faculty

members commented that they had heard ‘on the

grapevine’ that WebCT was too difficult and

time-consuming to use and hence decided not

to use it for those reasons. Furthermore, a number

of faculty members suggested that when they had

adopted WebCT, they learned how to use the system

from their colleagues. One faculty member provided a

useful illustration of the positive influence of

interpersonal networks:

“I learnt from another member of staff. I was

sharing the module with them and they were using

WebCT, and they showed me how to use it.”

However, another faculty member highlighted that

influence of such networks could be negative:

“I know someone that did become very keen and

very excited after attending the WebCT training

course, but at the end of the day they said it was

such hard work because they ended up creating so

much more work for themselves.” (Lecturer)

It is also important to note that during any of the

stages, the decision to use WebCT at that particular

level can cease. If the faculty member progresses to

a higher level of adoption, their experiences of

using WebCT at that level, together with shared

experiences of best practice with their peers can

influence them to make the transition back to a

lower stage of adoption. The research findings show

that this occurred with the ‘eager beaver’ group of

adopters. They initially experimented with various

advanced functions within WebCT, but their negative

experiences with the technology led them to using

the technology at a more basic level.

By identifying the different levels at which faculty

are using WebCT for course delivery appropriate

strategies can be put into place to encourage

progression to more advanced levels of use which

more fully utilise the potential of the technology.

This process requires understanding of the barriers

that influenced the decision of faculty members to

adopt and use the technology, namely:

·

lack of extensive deliberation between key

stakeholders of the university

·

lack of explicit guidelines for best practice of

WebCT

·

lack of a ‘needs analysis’ of faculty

·

inadequate training and support

·

conflicting priorities for faculty

Therefore, a number of practical recommendations for

other universities implementing

CMS such as WebCT to arise from the case study research

as follows:

Recommendation 1:

Encourage extensive and open communication with key

stakeholders of the university.

The first stage in facilitating the successful

integration of CMS in higher education institutions

requires open and extensive deliberation to occur

amongst all the stakeholders, for example,

management, faculty, student representatives,

administrative staff, other support staff and online

learning steering group members (if a steering group

exists). These stakeholders should be encouraged to

attend informal meetings on an ongoing basis to

discuss their experiences of engaging with online

learning technology. Such meetings enable all

stakeholders to become part of the process and

facilitate the successful diffusion of the

technology.

Recommendation 2:

Identify individual training and support needs for

faculty based upon their user profile

Faculty have diverse sets of IT skills and therefore

require different levels of support. However,

training provided for faculty tends to be generic

and fails to take into account the individual IT

skills levels and the various attitudes towards

WebCT that faculty members hold. To encourage more

efficient use of CMS systems, a comprehensive IT

skills survey should be conducted with faculty to

clarify these issues and customise the training

accordingly as part of a formal process, leaving the

option of participating in the IT and

CMS training as voluntary on the part of the faculty

member.

Recommendation 3:

Involve ‘e-fellows’ as mentors and project champions

Utilise faculty members, final year undergraduate

students or postgraduate students with a background

and interest in computing related fields as

‘e-fellows’ to support less experienced faculty with

the development of their web bases and online course

delivery skills. Such a strategy would be

beneficial at several levels:

-

It is cost effective as it would

not require any additional staff to be employed,

but makes use of existing resources.

-

Individualised support would ease the pressure on faculty and

allow them to devote more time to their research

and teaching related activities.

-

Personal support and tuition from

an expert will encourage the use of WebCT at more

advanced levels and help to optimise the full

potential of the technology.

-

Champion’ the benefits of the

technology

Recommendation 4:

Develop explicit guidelines for ‘best-practice’ use

of

CMS

It is crucial that transparent policies and

procedures form the basis of the online learning

strategy, so that both faculty and students are

aware of what is required of them. These policies

should specifically address faculty concerns over

ownership of knowledge and copyright restrictions.

Equally, the development of explicit guidelines will

make it clear to students what they can expect from

faculty members so as to establish appropriate

boundaries between the two. The information should

also be clearly conveyed to administrative staff.

Table 1 below outlines specific recommendations to

facilitate this process.

Table 1. Specific recommendations to facilitate

“best-practice use” of CMS.

|

USER PROFILE |

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTION BY E-FELLOWS |

|

Drivers |

·

Encourage their key role as ‘champions of online

learning technology.

·

Reward drivers for dissemination of best

practice through departmental seminars and

informal networking. |

|

Eager Beavers |

·

Provide specific training in advanced or new

features of the technology, such as developing

forms of online assessment or managing online

seminars.

·

Encourage liaison with Drivers |

|

Piggy Backers |

·

Focus training on the development of skills to

use technology autonomously and at a more

advanced level, such as managing discussion

boards (see Figure 1)

·

Build confidence in use of the technology in

order to convert user to an Eager Beaver over

time |

|

Coerced Sceptics |

·

Work with this group to develop skills to use

the technology at a basic level, such as

creating links and the uploading of course notes

and reading lists (see Figure 1)

·

Demonstrate the benefits of using the system

·

Establish the reasons for resistance and work

closely with the user to address their concerns

|

|

Vigilantes |

·

Drivers and Eager Beaver groups need to work

together with the Vigilantes to promote the

benefits of using the technology through

informal networking

·

This group will need to be encouraged by peer

pressure to move initially from ‘no adoption’ to

using the technology at a ‘basic level.’

·

Assist the Vigilantes in ongoing maintenance of

the web-base to address the issue of time

constraints, then gradually step back over the

longer term to encourage more independent use

·

Ensure modules are jointly taught with Eager

Beaver tutors paired with Vigilantes in order to

lead by exampl |

It is important to note that this strategy relies on

the willingness of faculty and students to partake

in such apprenticeship roles. E-fellows will focus

on building the skills required to encourage faculty

members to use WebCT at more advanced levels as

identified through the initial skills audit

conducted.

Conclusion

The findings from this case study research report on

the use of WebCT for course delivery by faculty in a

traditional campus-based UK university. The research

findings have demonstrated that using traditional

models of critical mass in isolation is a misleading

indicator of the successful diffusion of CMS, such

as WebCT, due to the multi-functionality that such

CMS afford. The adopter categories identified provide

evidence that individual characteristics displayed

by faculty influence both the pace and degree to

which these faculty members used WebCT and allowed

the researchers to develop a series of both generic

and targeted recommendations for effective diffusion

and more efficient use of

CMS for course delivery. The research as a whole

highlights that a number of organisational and

social issues compromised the use of WebCT by

faculty.

References

Abrahams, D.A. (2004) “Technology Adoption in

Higher Education: A Framework for Identifying and

Prioritising Issues and Barriers to Adoption”,

Doctoral Thesis,

Cornel University, USA.

Allen,

I. E. and Seaman, J. (2007) Online Nation: Five

Years of Growth in Online Learning, Babson

Survey, The Sloan Consortium, USA.

Dearing,

R. (1997) The

Dearing Report - National

Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education.

London

DfeS (2005) “e-learning strategy” [online]

http://www.dfes.co.uk/elearningstrategy 2005

Feagin, J. Orum, A. and Sjoberg, G. (1991) A Case

for Case Study,

Chapel Hill,

University of North Carolina Press.

Ferneley, E.H. and Sobreperez, P (2006) “Resist,

comply or workaround? An examination of different

facets of user engagement with information systems”,

European Journal of Information Systems,

vol.15, no 4, 345-356.

Garrett, R. (2004) “The Real Story Behind the

Failure of

U.K. University”, Educause Quarterly, no.4.

pp. 4-6.

Geoghegan, W.H. (1994) “Whatever Happened to

Instructional Technology?” 22nd Annual

Conference of the International Business Schools

Computing Association.

Baltimore, MD, [online]

http://www.franklin.scale.uiuc.edu/scale/links/library/geoghegan/wpi/html,

Glaser, B.G. and Strauss, A.L. (1967) The

Discovery of Grounded Theory: Issues and

Discussions, Sociology Press,

Mill Valley,

California, USA.

Green, K.C. (2003) “The New Revisited Computing”,

EDUCAUSE Review, pp. 33-43.

Jacobsen, D.M. (2000) “Examining Technology Adoption

Patterns by Faculty in Higher Education”,

Proceedings of Ace 2000, Learning Technologies,

Teaching and the Future of Schools,

Melbourne, Australia.

Littlejohn, A., and Higgison, A. (2003) “A Guide for

Teachers”, LTSN E-Learning Series, no. 3,

York: LTSN.

Quinsee, S. and Hurst, J (2005) “Blurring the

Boundaries? Supporting Students and Staff within an

Online Learning Environment”, Turkish Online

Journal of Distance Education-TOJDE, January,

vol.6, no.1. pp.1-8.

Ramsden, B (2007) Patterns of Higher Education

Institutions in the

UK:

Seventh Report, Universities

UK.

Rogers, E.M. (1995) Diffusion of Innovations,

4th edition,

New York,

NY.

Rogers, P.L. (2000) “Barriers to Adopting Emerging

Technologies in Education”, Journal of

Educational Computing Research, vol. 2, no. 4,

pp. 455-4 72.

Shimabukaro, J. (2005) “Freedom and Empowerment: An

Essay on the Next Step for Education and

Technology”. Journal of Online Education,

June-July, vol. 1, issue 5, pp. 1-6.

Souleles, N. (2004) “A Prescriptive Study of Early

Trends in Implementing E-Learning in UK Higher

Education”, Cumbria Institute of Arts, Working

Paper [online]

http://it.coc/ittorum/paper/8/paper/8.htm

Yin, R.K. (2003) Case Study Research, Design and

Methods, 3rd edition, Applied Social

Science Research Methods Series, vol.5

|