Background on Student Competitions

Today’s college students expect stimulating and innovative educational experiences in order to maintain their interest and create a memorable encounter (Elam and Spotts 2004; Matulich, Papp and Haytko, 2008; Ueltschy, 2001), such as various student competitions. Research supports the use and benefits of such student competitions. An early study found that simulated play related positively to exam scores, yet when controlling for the marketing students’ GPA, there were no significant differences ( Wellington and Faria, 1991). The authors concluded that multiple choice exams measure recognition of basic concepts and principles, while simulation develops decision making skills. Drawing on marketing concepts to develop decision making skills also helps prepare students for job market expectations (Gillentine and Schulz, 2001).

Extending the classroom experience from simulations to national or global competitions adds the benefits of real world applications, industry standards for grading students, and a compelling learning experience anchored in an industry context. Gentry (1990) argued that working with live businesses is a “prominent pedagogy” due to its strong learning potential and value as an experiential learning activity. A major objective of most business programs is to ensure that graduates enter the workplace as prepared as possible to succeed.

Classroom experiences as similar as possible to real world experiences benefit students through hands on experiences, business competencies, and critical skills (Hawes and Foley, 2006; Rundle-Thiele & Kuhn, 2008, Stern and Tseng, 2002). A survey of students that competed in SIFE (Students in Free Enterprise) and AAF/NSAC (American Advertising Federation National Student Advertising Competition) found strong competition benefits such as a positive experience, emotional attachment to the university, and significantly better learning relative to other project-based classes (Stutts and West, 2003). Similarly, students competing in a robotics competition gave the course much higher ratings than the departmental average and only slightly above average ratings on work load (Murphy, 2000). This design competition provided both motivating examples of how abstract concepts transfer to practice and meaningful assignments and projects.

Competitions enhance education and usually benefit three constituents: students, industry, and educational institutions. Real-world and practical education gives students lifetime benefits such as entrepreneurial skills, self-confidence, risk-taking propensity, access to mentors, and networking opportunities (Russell, Atchison and Brooks, 2008). The educational institutions gain strong community and industry links, which can result in student employment and research opportunities.

Learning Objectives

With the focus on online marketing, the Google Online Marketing Challenge introduces the students to one of the most important and fastest growing sectors in online marketing communications. Internet advertising is projected to grow 15 - 20 percent through 2011 (IDG, 2008) , and in 2007, Google earned $16.4 billion with over 90 percent of this revenue from its key product, AdWords, and related services (Google, 2007). The Challenge allows students to apply marketing theories in a uniquely applied manner to an important and growing environment.

Unlike simulated or fabricated student competitions, the Challenge is a problem-based learning approach (PBL), whereby student teams engage in facilitated, self-directed learning to solve a complex problem with no single correct answer (Hmelo-Silver, 2004). PBL helps develop flexible understanding and lifelong learning skills as “students become reflective and flexible thinkers who can use knowledge to take action” (Hmelo-Silver, 2004, p. 261). In the Challenge, students are active learners involved in an online marketing campaign, facing real pressures similar to those in the professional work place (i.e., client relationships, financial constraints, market competition, and time limitations). Student teams work with real clients on a real marketing platform using real money. Throughout their campaigns, the students continually make finance, advertising, and marketing decisions. As such, the Challenge does an excellent job of reflecting the professional work environment and PBL.

A common objective of marketing education is helping students understand real-life applications of marketing concepts (Stern and Tseng, 2002). Another objective of many marketing professors is incorporating experiential learning in the classroom so students can work with real businesses (Hawes and Foley, 2006; Li, Greenberg, and Nicholls, 2007). The Challenge helps students learn effective online marketing via sound market analysis to optimize, manage, and update a Google AdWords campaign (discussed in the next section). Students gather real world data and use Google AdWords as the platform for gaining a stronger understanding of online marketing. Students experience traditional advertising concepts such as copywriting, conversion rates, cost per thousand (CPM), return on investment, as well as online marketing concepts such as click-through-rate (CTR), cost-per-click (CPC), landing page strategies, and optimization techniques. After participating in the Challenge, students should be able to:

- understand the complexity of implementing an online marketing campaign;

- create a practical and successful campaign that fits with the objectives of their client;

- maximize targeted and relevant traffic to their client’s Website;

- use optimization techniques to refine and improve the effectiveness of the campaign over the three-week competition period;

- confidently discuss online marketing and media planning issues with their client; and

- illustrate the technical and cultural factors affecting the success of online marketing campaigns.

Students demonstrate understanding of these concepts via creation of a Pre-Campaign Strategy Report and Post-Campaign Summary Report (discussed below). That students must communicate their ideas and experiences in these reports enhances the academic value of experiential learning (Hawes and Foley, 2006; Matulich, Papp and Haytko, 2008; Young, 2002).

Overview of the Challenge

The Google Online Marketing Challenge (the Challenge) is an educational innovation that sensitizes students to the complexities associated with online marketing, while simultaneously helping students develop insights about working with real business clients. The Challenge is a global business student competition developed by professors in collaboration with Google (www.google.com). Unlike most student competitions that follow a simulation or hypothetical scenario, students gain experience by working with actual businesses in real-time with a defined budget. In the inaugural 2008 competition, over 8,000 students in 1,620 teams from 47 countries across six continents competed (c.f., Jansen, Hudson, Hunter, Liu, and Murphy 2008).

Through the Challenge, students learn how to develop and implement an online marketing campaign to drive online traffic to small-to-medium-sized enterprises’ (SMEs) Websites using Google AdWords, Google’s flagship advertising product. AdWords provides a simple and quick way to advertise on Google.com and millions of independent Websites that form Google’s content network. Table 1 below illustrates two example Google AdWords ads, which could show up on the results page of a Google search for the phrase “online education.” The first line of the ad has a maximum of 25 characters including spaces and the other lines have a maximum of 35 characters. In a Google search query, AdWords advertisements would be displayed above and alongside the organic search results.

Table 1. Sample AdWords Ads

For three weeks, students evaluate statistics and adjust the live campaigns accordingly. Teams of three to six students compete on campaign metrics and submit two written reports that address: learning objectives and outcomes; group dynamics and client dynamics; how campaign strategies evolved; and future recommendations. Google provides an Academic Guide and printed text, Marketing and Advertising Using Google, for instructors and three eBooks for students (Student Guide, Guide to Setting up your AdWords Account, and Marketing and Advertising Using Google). Table 2 lists these and other Challenge-related resources.

-

-

Keyword Research with Christine Churchill and Ralph Wilson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oIb05Fu_9qk

-

-

There are four major phases to implementing the Challenge in a course:

1. Recruit SME : Once students are formed into groups, they select a Team Captain. Next, the student teams recruit an SME (i.e., business, governmental, or non-profit) with under 100 employees, that has a Website but does not currently use Google AdWords. To help students, Google’s Student Guide includes a section titled “Selecting and Working with a Business or Organization.” Once a suitable client is found, the students deliver a Letter to Business that explains the Challenge and what SMEs can expect from participation. Businesses simply need to agree verbally that the students may promote their Website using Google AdWords.

2. Develop Pre-Campaign Strategy : Student teams work with the businesses to understand their goals and to then structure an online marketing campaign documented in a Pre-Campaign Strategyreport. This short report contains a client overview and proposed AdWords campaign strategy covering criteria such as keywords, text advertisements, budgeting, and geo-location targeting. Students upload the Pre-Campaign Strategy report to the Challenge Website, as well as deliver it to their client and instructor.

3. Establish AdWords Accounts and Run Campaign: Teams set up the basics of their AdWords account and receive an online advertising voucher worth US$200. During a 3-week Competition Window, teams implement their proposed campaign strategy, review their results frequently, run reports, and adjust their campaigns accordingly. To accommodate teams in myriad countries, teams could run their campaign any time between mid-February and mid-May as long as it was three consecutive weeks.

4. Develop Post-Campaign Summary : Upon completion of their campaign, teams evaluate the campaign, document findings in a Post-Campaign Summary report, upload the Summary to the Challenge Website, and deliver it to their client and instructor. This report addresses how well the team researched their client, provided a reasoned AdWords strategy, and learned from the experience. It includes an industry component, a learning component, and encourages the use of tables, figures, and charts to illustrate campaign results.

Google and then a global panel of academics judged the entries, with teams competing for global and regional prizes. The Challenge employed a multi-level approach involving an algorithmic evaluation of the teams’ campaigns, followed by a qualitative campaign evaluation, and then an evaluation of the two written reports. First, Google judged each team's campaign statistics such as account impressions, cost-per-click, click-through-rates, keywords, ads, budgets, and more. To measure the effectiveness and management of accounts, Google used a proprietary algorithm that assessed five aspects of team performance: (1) account structure, (2) optimization techniques, (3) account activity and reporting, (4) relevance, and (5) performance and budget. Based on the algorithm, Google trimmed the 1,620 teams to 150 teams. Next, Googlers manually winnowed these 150 teams to 15. In the final phase, an academic panel of over a dozen professors from eight countries selected the eventual winners based solely on the teams’ two written reports. Two panelists with teams in the final 15 abstained from judging the written reports. Detailed information is available on the official Challenge Website.

Table 2. Resources for the Challenge

Google Online Marketing Challenge eBooks

- The Student Guide is a 23-page document that provides answers to frequently asked questions, a suggested timeline, advice for selecting and working with businesses, a brief overview of online marketing and Google AdWords, Challenge criteria and grading, and terms and conditions. https://www.google.com/onlinechallenge/student_guide.pdf

- The Guide to Setting up Your AdWords Account is a 19-page guide that walks students through managing an account, making the most of campaigns, judging criteria, and resources and support. https://www.google.com/onlinechallenge/adwords_setup_guide.pdf

- The Marketing and Advertising Using Google Textbook is a detailed, 156-page resource that helps students learn about AdWords through readings, activities, and quizzes. It includes topics such as Google search marketing, successful keyword targeted advertising, image and video ads, local and mobile advertising, and tracking performance. https://www.google.com/events/business_educators/files/MarketingAndAdvertisingUsingGoogle.pdf

- The professor’s Academic Guide contains material similar to the three student eBooks but also includes information of interest to professors such as managing student teams and setting up a timeline (18 pages). https://www.google.com/onlinechallenge/professors_guides.html

Getting started with Google AdWords

Managing and Optimizing an Account

Video and Other Resources

|

|

Implementing the Challenge

At the end of the inaugural Challenge, the Google Online Marketing Challenge Research Center (2009) administered customized online surveys for each of the three participating groups: professors (n = 136), students (n = 687), and businesses (n = 103) (c.f., Neale et al. 2009 for questionnaire development, administration and subsequent data cleaning of these surveys). The authors evaluated open-ended responses from participating professors using a modified critical incident approach (Gremler, 2004), specifically: What factors frustrated you with the Challenge? (n= 143, no response = 21), Did your search engine advertising, online marketing, etc., experience prior to this project (or lack thereof) affect your ability to lead the project? How did you leverage/overcome these strengths/weaknesses? (n= 130, no response = 31), and What suggestions would you make to improve the Challenge? (n = 140, no response = 32 ). From the analysis, three broad concerns with the Challenge were identified by participating professors: (1) getting up to speed for the Challenge, (2) teaching the students, and (3) tactical issues. We address each of these issues in order to provide guidance for successful implementation of the Challenge.

1. Getting up to Speed for the Challenge: Marketing faculty often face obstacles in adopting innovative technologies (Li, Greenberg, and Nicholls, 2007; Matulich, Papp and Haytko, 2008). Certainly, this is true for professors without Google AdWords experience, as this was the number one issue professors reported concerning the Challenge. As with any new course, instructor preparation and expertise is a major component of success. The authors recommend two pre-requisite tasks in order for professors to feel adequately prepared to run the Challenge.

First, professors should avail themselves of the resources presented earlier in Table 2, including eBooks provided by Google (Academic Guide,Student Guide, Guide to Setting up your Account, and Marketing and Advertising Using Google). The four eBooks contain valuable information to help get professors up to speed for the Challenge. In particular, Marketing and Advertising Using Google is an outstanding resource for instructors, and it can be read very rapidly. The authors recommend that professors carefully read all four eBooks, and if deeper AdWords knowledge is desired, explore the additional resources in Table 2.

Second, even though the AdWords online interface is very user-friendly, professors are advised to run a simple AdWords campaign themselves prior to beginning their course. It is free to setup an account and use all the integrated tools of keyword selection, advertisement creation, and traffic estimation. In addition, upon request, Google will provide a free US$ 50 voucher to participating professors. Suggested clients for professors to run an AdWords campaign could be their own Website, student clubs, or a departmental Website. The goal is for professors to grasp how AdWords operates, become familiar with the AdWords interface, see the statistics the platform provides, develop advertisements, and understand the reporting tools.

2. Teaching the Students: A real-world marketing experience in a course is a great opportunity, albeit with risks, in presenting useful material. Although the Google AdWords platform is feature rich, instructors should address at least three AdWords components with students: the traffic estimator tool, ad creation, and online market analysis. Brief exercises for each component for instructors to assign as an optional in-class or out-of-class exercise follow.

- Traffic Estimator Exercise : This handy tool estimates the potential search traffic a keyword will generate, and thus helps select what terms to use for each Ad Group within the team’s campaign. The traffic estimator lets students try potential key phrases and provides estimates of the number of impressions each phrase might garner in a given period. A learning exercise to familiarize students with this tool may involve development of a spreadsheet or table that summarizes and compares findings from 5-10 different keywords and phrases. Students can log into their AdWords account and use the Traffic Estimator to report: minimum bids required for a keyword, the maximum cost-per-click associated with a keyword, search volume to determine how competitive ad placement is for a particular word, estimated average cost per click, and estimated ad position. See www.adwords.google.com/support/bin/topic.py?topic=1502 for further information about the Traffic Estimator tool.

- Ad Creation Exercise : Students should practice crafting ads in order to feel comfortable making adjustments to ads during the three-week campaign window. Prior to the campaign as an exercise, students can log on to AdWords and develop sample ads to share and critique online. The sample ads could be about their client’s business or an instructor-assigned topic. Key areas to evaluate in ad development include: consumer motivation to click the ad, search terms showing up in the ad’s title, descriptive URLs, a call to action in the ad copy, and meeting Google’s editorial guidelines for ads. For example, Google will not run ads for alcohol or educational aids such as services that sell student essays. For further guidance on Google’s Editorial and Format Policies, please see https://adwords.google.com/support/bin/static.py?page=guidelines.cs&topic=9271&subtopic=9277

- Online Market Analysis Exercise: It is helpful for students to develop a thorough understanding of the competitive landscape before developing their campaign. As an exercise, students should search for competitors using key phrases that they plan to bid on. Students should analyze the ads that appear in order to see how intense the competition is, who their competitors are, and the positioning of the competition. In addition to understanding what the competition is doing, this is a good technique for selecting a client SME

3. Tactical Issues : Although several variations exist, professors can take one of three general approaches to deliver the Challenge: (1) Out of Class with little or no class time devoted to the Challenge, (2) Partially in Class where the Challenge is a component of a course and some class time is devoted to the Challenge, and (3) In Class where the Challenge is the, or a major component of, a course. Table 3 illustrates example timelines and topics for each of these three approaches, which were used successfully by the authors, to show how other instructors might schedule Challenge activities. Some instructors might prefer a great deal of in-class time for the Challenge while others may opt for student work outside of regularly scheduled class time. With ample support materials and structured outcomes, the Challenge offers great flexibility in implementation.

Table 3. Sample Timelines to Structure the Challenge based on Percentage of **In-Class Course Time Devoted to the Challenge

Week |

Out of Class

Minimal in-class contact hour scenario targeted to the professor who may not be an expert or comfortable or does not have much in class time for the Challenge. Extra credit project, totally out of class, and/or minimal meetings with instructor. (0-6 hours) |

Partially in Class

Some in course time and when the Challenge is a component of a more all encompassing course. (7-9 hours) |

*** In Class

High class time. Ideal for a special topics class. Also ideal for classes taught in a computer/teaching lab or classroom where students have Internet access. (10 or more hours) |

1 |

* Introduction to Challenge and students divided into teams. |

* Introduction to the Challenge. |

* Introduction to Search Engines, Search Engine Marketing, and Sponsored Search |

2 |

Students read the Google eBooks. |

* Students divided into teams. |

* Establish AdWords Accounts, AdWords Overview and Selecting Businesses

* Students divided into teams. |

3 |

Students read the Google eBooks.

|

Students recruit a SME |

* The Three Course Requirements (Strategy, Campaign, and Assessment) |

4 |

Out-of-Class Exercises: Traffic Estimator, Ad Creation, and Online Market Analysis |

Students read the Google eBooks.

Establish AdWords Accounts |

* Successful Keywords and Campaigns

* In-class Exercises: Traffic Estimator, Ad Creation, and Online Market Analysis |

5 |

Students recruit a SME |

* In-class instruction on Search Engine Marketing ( SEM).

Out-of-class Exercises: Traffic Estimator, Ad Creation, and Online Market Analysis |

* Tracking Performance

Students recruit a SME |

6 |

Establish AdWords Accounts |

* Continue in-class instruction on SEM and guest speakers. |

* Clients and Stakeholder Analysis

* Develop the Pre-Campaign Strategy. |

7 |

Independent teamwork to develop the Pre-Campaign Strategy. |

Mix of in-class and out-of-class time to develop the Pre-Campaign Strategy. |

* Campaign Strategies

Teams submit the Pre-Campaign Strategy to instructor, client, and Google. |

8 |

Independent teamwork to develop the Pre-Campaign Strategy. |

Mix of in-class and out-of-class time to develop the Pre-Campaign Strategy. |

* Prepare for Three Week Campaign |

9 |

Semester Break |

Semester Break |

Semester Break |

10 |

* Mid-semester AdWords Strategy Session with Professor. |

Teams submit the Pre-Campaign Strategy to instructor, client, and Google. |

* Campaign Week One |

11 |

Teams submit the Pre-Campaign Strategy to instructor, client, and Google. |

* Campaign Week One – 15-20 minutes devoted to the Challenge at the end of each class |

* Campaign Week Two |

12 |

Campaign Week One |

* Campaign Week Two – 15-20 minutes devoted to the Challenge at the end of each class |

* Campaign Week Three |

13 |

Campaign Week Two |

* Campaign Week Three – 15-20 minutes devoted to the Challenge at the end of each class |

* Analysis of Campaign Success

* Develop the Post-Campaign Summary. |

14 |

Campaign Week Three |

*Mix of in-class and out-of-class time to develop the Post-Campaign Summary. |

* Teams submit the Post-Campaign Summary to instructor, client, and Google. |

15 |

Teams submit the Post-Campaign Summary to instructor, client, and Google. |

Teams submit the Post-Campaign Summary to instructor, client, and Google. |

* In-class Presentation of Campaign Results to client. |

16 |

Finals Week |

Finals week |

Finals week |

* Denotes in-class time devoted to the Challenge. Detailed Challenge information is available on the official Website, https://www.google.com/onlinechallenge.

** On average, professors report allocating a median of 8.2 hours of in-class time towards the Challenge, with a range of 0 to 40.

*** Within the “In Class” version, each course lesson focused on an aspect of the Challenge. Given the possible mix of students, the stand alone course began with a review of search engines as indispensable tools for locating information, but also to facilitate e-commerce transactions. This was followed by introductions showing how many organizations are using search engines for online marketing, branding, and advertising. The remainder of the course lessons examined the online marketing environment via the Challenge, with an emphasis on the Google AdWords platform and tying this platform to larger technology, marketing, and advertising themes.

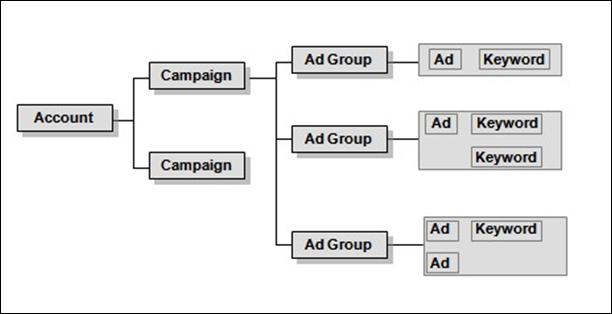

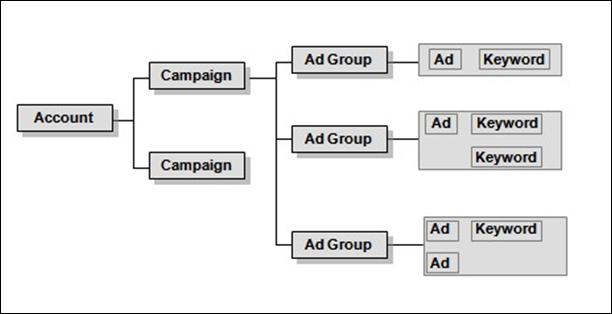

Although a team project, the Challenge allows for individual accountability. One way of ensuring this is making each team member responsible for an AdGroup (i.e., a sub-component of closely related terms on a specific topic and associated advertisements) within the team’s campaign. Thus each student can have his or her own set of keywords and ads to manage, for example associated with one product from the client’s product line. With each team member in charge of one or more AdGroups, there is individual accountability, but it requires team coordination for budgeting and keyword coordination. As can be seen in Figure 1, under each Google AdWords account there may be multiple campaigns. A variety of settings are controlled at the campaign level, including the daily budget, geographic targeting, time of day scheduling, and ad position ranking on the Google search results page. Under each campaign, there may be a variety of AdGroups. An Ad Group might, for example, have two ads as in Table 1, and those ads might share the same keywords, or have different sets of keywords.

Figure 1. Basic Structure of a Google AdWords Account

Given the realistic nature of the Challenge, professors should advise teams of implementation issues. First, the teams must recruit an SME. It is important to alert students that the type of business they pick will impact the execution and performance of their campaigns. For example, there may be issues with the timing of campaigns involving flower shops in the United States, who sell mostly during Mother’s Day and Valentine’s Day. To succeed, different teams will necessarily have different campaign strategies.

Second, students must consider the myriad aspects of working with different types of clients. The more the client collaborates with the student teams, the better the experience for all parties and the better the online marketing campaign. Although it may be easy for professors or students to recruit client SMEs, the focus should be on willing clients. Professors could contact the local Chamber of Commerce, Small Business Association, or Alumni Association for a list of potential SMEs. Ideally, students will consider several clients and choose the best alternative.

Third, once the teams have chosen their SME, they set-up an AdWords account for this SME and Google provides each team with a US$200 voucher. The teams have to be ready at the start of the three-week competition window, but should not activate (turn on or start running) their campaigns early. Professors may wish to hold the vouchers until students are ready to start their campaign. This step reduces accidental activation of the campaign, and the handling of the voucher provides a good evaluation milestone; the professor can review the campaign before the voucher hand-off.

Finally, the Challenge comes with explicit instructions for students to develop their Pre-Campaign Strategy and Post-Campaign Summary reports. Instructors have two ready-made assignments with detailed guidelines and clear assessment criteria.

Refer to https://www.google.com/onlinechallenge/academic_guide.pdf for grading criteria to evaluate each report. Instructors can add additional assignments, change the grading criteria, or modify the reports for their own course grades. Refer to https://www.google.com/onlinechallenge/students_guides.html for information on the Pre-Campaign Strategy and Post-Campaign Summary reports. For the inaugural Challenge, a few undergraduates reported that it was somewhat difficult to follow some instructions while graduate students seemed to more successfully navigate and follow the Challenge materials. Instructor ‘hand-holding’, and performance expectations, may need to vary accordingly.

Conclusion

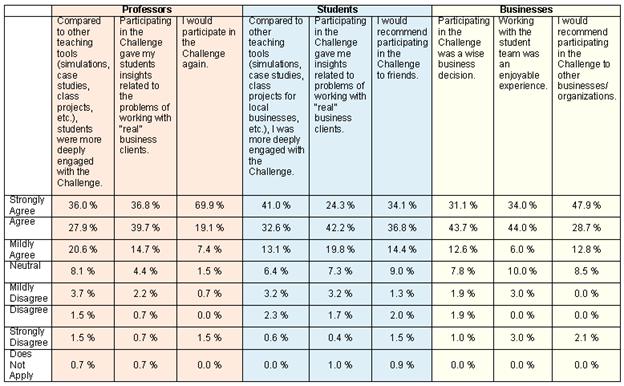

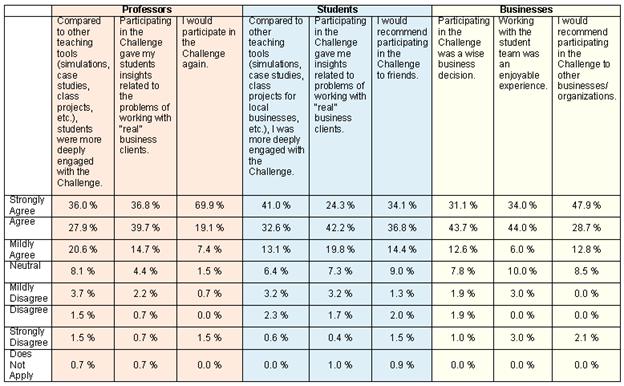

According to results presented on the Google Online Marketing Challenge Research Center (2009), the Challenge was extremely successful in accomplishing the pedagogical aims outlined above; 94 percent of professors and 92 percent of students reported being pleased with the experience. The businesses were also pleased, as 89 percent would recommend participating in the Challenge to their colleagues. The results in Table 4 indicate high overall satisfaction from all involved groups. Of noteworthy importance is that students and professors report more student engagement with this project compared to other teaching tools such as cases and simulations. As a final measure of satisfaction, professors, students, and businesses overwhelmingly indicated they would participate in the Challenge again.

Table 4. Participant Satisfaction with the Challenge - Professors, Students and Businesses

While different student levels require unique pedagogical approaches, it should be emphasized that the Challenge is extremely flexible and was successfully implemented in different levels of classes from community college to graduate classes (Murphy, Tuzovic, Ling, and Mullen, 2009; Oliver, 2008; Rosso, McClelland, Jansen, and Fleming 2009). The Challenge also adapts to a wide variety of clients and cultures as the 2008 Challenge ran in 47 countries across six continents. Professors can implement the Challenge in a wide assortment of marketing (e.g., Internet Marketing, E-Commerce, IMC, Advertising, etc.) and non-marketing courses (Information Systems, Hospitality, Management, Media Arts, Economics, etc.).

The student involvement in and enthusiasm for the Challenge was evident, as well as online networking opportunities and discussion forums for the participants (c.f., Lavin et al. 2009; Ling 2008). For instance, enterprising students at a major university set up a n unofficial social network (The Google Online Marketing Challenge Network ) for all teams in the Challenge (www.gomcha.com). This social network grew to over 340 members by the 2008 competition’s end and has almost 700 members in 2009. Professors created their own sub-group within the network for discussions away from prying student eyes. There was also a Challenge-oriented Google Group (groups.google.com/group/onlinechallenge) where professors and students from all over the world came together to communicate and collaborate.

In summary, there is much to recommend about the Challenge. It is perfectly suited to modern conceptions of active and problem-based learning, and experiential pedagogy. It uses a new online marketing form that represents one of the most innovative components of the economy, a component expected to maintain torrid growth in the future. The Challenge involves students with actual SMEs solving real advertising problems, and is highly adaptable across various course levels and curricula. To top it off, survey results indicate that all participants – businesses, instructors and even students – enjoyed it. In the future, the Challenge will be available for instructors all over the world. Instructors should seriously consider adopting it for their own courses. |