Introduction

Many universities with online programs are facing

the same challenges of providing positive

identification of students enrolled in online

programs and reducing the occurrence of cheating

on assignments and tests. Some may require online

students to go to the campus or testing center to

take tests; some require the tests to be proctored

by a trusted agent; and others are searching for

technological solutions. Remote Proctor from

Software Secure (http://www.softwaresecure.com/)

is one such technological solution that provides

biometric identification and a secure, monitored

testing environment. This paper provides a case

study of the procedures used in the adoption and

implementation of Remote Proctor and other

technologies aimed at improving academic integrity

of degree programs at a small southern regional

university (hereafter, SSRU).

Background

SSRU is a state supported institution located in a

rural area of a southern state. It hosts

approximately 2,500 on-campus students enrolled in

undergraduate and graduate programs. SSRU also has

about the same number of students enrolled in its

online programs. The programs are accredited by

the Association of Collegiate Business Schools and

Programs (ACBSP), National Council for

Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE),

Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training

Education, National League for Nursing, and the

Southern Association of Colleges and Schools

(SACS). Like many universities, SSRU is attempting

to confront the issues of cheating, plagiarism,

and other forms of academic dishonesty in both

on-campus and online courses.

Cheating and Technology

Cheating is not a new phenomenon at colleges and

universities. Research into why students cheat

and how universities control these activities was

conducted as early as 1964 (Bowers 1964). More

recent research indicates that cheating not only

continues to be a problem, but for the 10 years

between 1992 and 2002, the incidents of cheating

increased dramatically (McCabe 2001-2002; McCabe,

Butterfield, & Trevino 2006). It also seems that

students increasingly think it is ok to cheat (Etter,

Cramer, & Finn 2006; Malone 2006; Roig & Ballew

1994).

Apparently, cheating has become such a prevalent

and compelling topic that a recent prime time

television show, Without a Trace (Steinbert

2009), used it as the theme. The episode

revealed ways that students cheat and addressed

one of the major reasons why they do it:

competition to get into universities. If society

is so very aware of high school students cheating

their way into college, then it stands to reason

that it can be expected once they arrive, as well.

SSRU incorporates a variety of

technologies in the classroom to enhance the

student’s learning experience. Wireless access to

the Internet, the Blackboard course management

system, lecture capture systems, and textbook

publisher resources provide rich content and

encourage student collaboration. These same

technologies, along with cell phones, text

messaging devices and Bluetooth networking

contribute to the increasing trend in cheating (Popyack,

et al. 2003) and make it easier for students to

cheat (Auer & Krupar 2001). Students are often

more familiar with the technology than the

instructors which makes cheating even more

difficult to detect. Using the Internet and a

myriad of search engines, students find applicable

websites and simply copy and paste the material,

claiming it as their own work (Akbulat, et al.

2008; Embleton & Helfer 2007), They use cell

phones and blackberries to text test questions and

answers to classmates; camera phones to take

pictures of tests; and laptop computers to look up

answers on the Internet (Popyack, et al. 2003).

There are also websites that sell or subcontract

term papers and projects written at any level on

any topic (Ross 2005). While technology seems to

facilitate student cheating, other technologies

such as software to lock down the testing

environment, cameras, biometric identification

devices, Bluetooth enabled computers to detect

other Bluetooth enable devices, and originality

checking applications can be used by universities

to combat cheating, both on and off campus and to

meet the demands of accrediting and regulating

agencies.

Academic Integrity in

Distance Education

In its Policy Statements on Distance Education,

SACS requires that “the integrity of student work

and the credibility of degrees and credits are

ensured” (SACS: CS 3.4.6 and CS 3.4.10 2008). In

order to maintain their accreditation (or be

reaffirmed), universities must demonstrate they

have processes in place that will reduce

opportunities for students to cheat. For its part,

SSRU implemented Turnitin.com as its first process

for enforcing its academic honesty policy.

Turnitin.com is an online resource used to verify

the originality of term papers and other writings.

Instructors or students submit papers to the

Turnitin.com database which then compares the

submitted document to others in the database and

on the Internet. A report is then generated that

identifies the percentage of material directly

copied from another source. The overall intent of

this implementation has been to reduce the amount

of copy and paste activity from the Internet.

The federal government has also placed

restrictions on universities with online programs.

The Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 (HEOA)

states “…the agency or association requires an

institution that offers distance education or

correspondence education to have processes through

which the institution establishes that the student

who registers in a distance education or

correspondence education course or program is the

same student who participates in and completes the

program and receives the academic credit” (HEOA:

Issue 10 2009). Many universities use proctors or

commercial testing sites to meet this requirement.

Students taking tests are either known by the

proctor or asked to show an ID and the testing

environment is monitored in an effort to

discourage cheating. SSRU is looking toward a

technological solution that will meet HEOA

requirements. As part of a research project on

cheating and technology, SSRU began evaluating the

usefulness of Remote Proctor to verify the

identity of online students and monitor

potentially suspicious activity in the online

testing environment. Remote Proctor uses a

combination of biometric authentication; software

controlled testing environment; and a 360O video

camera to discourage cheating. The next section

describes the decision process used.

Case Study

Early in 2008, the authors were researching ways

that students use technology to cheat in on-campus

courses and how faculty can use technology in the

classroom to discourage and detect cheating. The

research led to information on a project at a

nearby university which was conducting a trial of

Remote Proctor for testing in its online classes

(Powers 2006). Initial reviews from that

university were generally positive. Since SSRU has

an extensive online program; contact was made with

executives at Software Secure for more

information. Arrangements were made for a

representative of Software Secure to join a

presentation of the research on cheating at the

spring 2008 faculty colloquium to introduce Remote

Proctor to the SSRU faculty. Plans were made to

conduct a pilot study of Remote Proctor at SSRU.

Pilot Study on Remote Proctor

The pilot study was designed to test the Remote

Proctor device in a controlled environment to

simulate conditions for installation, registration

and testing. A small classroom was equipped with

five computers, each separated by partition. Each

student would be required to install the Remote

Proctor on their assigned computer and complete a

sample test. The study would provide information

about its ease of use by students and faculty, and

make a recommendation about the adoption of the

product in online courses. The results of the

study were presented at the fall 2008 faculty

colloquium and published in the Proceedings of the

51st Annual Meeting of the Southwest Academy of

Management (Bedford, Gregg, & Clinton 2009).

Additionally, the results were presented to the

SSRU Dean’s council who would be deciding the fate

of Remote Proctor. The pilot study and results are

summarized below.

Materials

Once a school adopts Remote Proctor, the device is

available to students for $150 plus $30 per year

software license. Software Secure provided SSRU

with five Remote Proctor units for a period of

30-days for evaluation plus a 30-day academic

license for Securexam for Remote Proctor software

to cover five students. The total cost of the

pilot study was $750.

Participants

Faculty members from all colleges (Table 1) were

encouraged to participate in this study. No

special criteria were required for participation

except an interest in improving the caliber of

online programs. An email was sent to

participating full-time faculty members with a

questionnaire attached. Instructors were asked to

visit the Remote Proctor web site to view the

videos taken during the test period and then

complete and submit a questionnaire about the

experience. Participating faculty included 40%

from the College of Business, 25% from the College

of Education, 10% from the College of Liberal

Arts, 5% from the College of Natural Science and

Math, 10% from the School of Nursing and 10% from

administrators who also teach online classes but

are not assigned to a college.

Table 1. Participating faculty

|

College/School |

Number of Responses |

|

Business |

8 |

|

Education |

5 |

|

Liberal Arts |

2 |

|

Natural Science & Math |

1 |

|

Nursing |

2 |

|

Other |

2 |

Due to the short time period of the study,

students in the

College

of Business were asked by their instructors to

participate in the study by taking one or more

prepared tests using Remote Proctor. The grades on

these tests were unimportant to the process. The

students installed the Remote Proctor hardware and

software, enrolled their credentials (fingerprint

and photo), and took one or more tests on the

Software Secure Blackboard site. The students were

encouraged to shuffle papers, talk, use their cell

phones and perform other activities that would be

captured as suspicious video by Remote Proctor and

recorded to the administrative site. After

completing the test(s), the students completed a

short questionnaire about their perceptions of the

process. The results from the student and faculty

questionnaires are presented in the analysis

section of this paper. Table 2 provides a

breakdown of the participating students by rank

and gender. Freshmen and sophomores were likely to

be taking classes in other colleges as well as the

College

of

Business;

juniors and seniors were likely to only be taking

courses in the College of Business.

Table 2. Student demographics

|

Rank |

Gender |

|

|

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

Freshman |

5 |

0 |

5 |

|

Sophomore |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|

Junior |

5 |

3 |

8 |

|

Senior |

11 |

3 |

14 |

|

Total |

23 |

8 |

31 |

Process

For the purposes

of this study, Software Secure prepared three

courses on its Blackboard site along with sample

Remote Proctor tests. Since the purpose of the

study was to examine the usefulness of Remote

Proctor to identify the student and monitor the

test environment and not to test the students

knowledge of any subject, these sample

exams were deemed

sufficient to evaluate the Remote Proctor testing

system for our purposes. These prepared exams

precluded faculty from having to prepare and

upload special exams just for this project.

Students

It was desirable to have as many students as

possible participate in this study. The actual

number (31) of participants was sufficient to

provide a statistically normal sample. Online

students using Remote Proctor to take an online

exam will be required to register their

credentials (fingerprint template and picture),

login to the test site and complete the test.

Remote Proctor will authenticate the person taking

the test and monitor the test environment for

suspicious activity. To make the experience

reflect, as closely as possible, a typical online

student testing situation, each student was

required to do the following

·

review installation instructions and other

documentation;

·

assemble the Remote Proctor;

·

install the software and hardware following

the instructions provided;

·

register the installation and enroll their

credentials;

·

logon

to the Software Secure Blackboard site and

take the exam(s).

As a test of the Remote Proctor capabilities,

students were asked to perform activities that

activate the suspicious activities monitor (talk,

open a book, etc.). The activities were captured

and recorded on a test site for viewing by

faculty.

After finishing the tests and closing Blackboard,

the students completed a short questionnaire. The

entire process (installation, registration, exam

and questionnaire) took the student about one-half

hour to complete.

Faculty

All faculty members were emailed a copy of the

questionnaire and encouraged to participate in

this study by doing the following:

Userid for Faculty =teacher-b

Password =teacher-b;

Twenty faculty members from across all colleges

responded to the questionnaire.

Analysis

Excel was used to provide the statistical analysis

of the student and faculty questionnaires.

Demographic data was collected from the student

and is shown in Table 2. The sample was 74% male

and 26% female. A majority of the students were

juniors and seniors. Only four of the students

reported they had taken online classes at SSRU;

however, nine indicated plans to take online

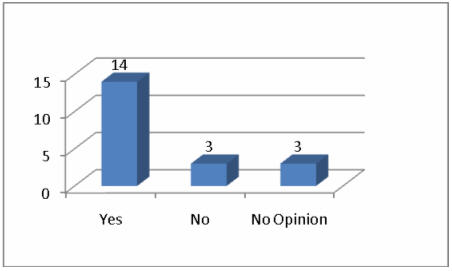

courses. As illustrated in Figure 1, 48% of the

students were supportive of adopting Remote

Proctor while 22% were not supportive and 30%

expressed no opinion.

Figure 1. Student recommendations

Acceptance and Adoption

The successful adoption of a new technology is

frequently determined by two primary factors:

perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use

(Davis, 1989). Perceived

usefulness is defined as the degree to which users

believe that the technology will facilitate the

process. The process evaluated in this study was

reducing opportunities for cheating and was

addressed in questions 6, 7, and 8. Perceived ease

of use is defined as the degree users find the

effort involved in using the technology as

minimal. This factor was addressed in the student

questionnaire by questions 10, 11, 12. They were

also addressed in the faculty questionnaire by

questions 1, 3, 4 (ease of use), and 5, 6, 8

(perceived usefulness).

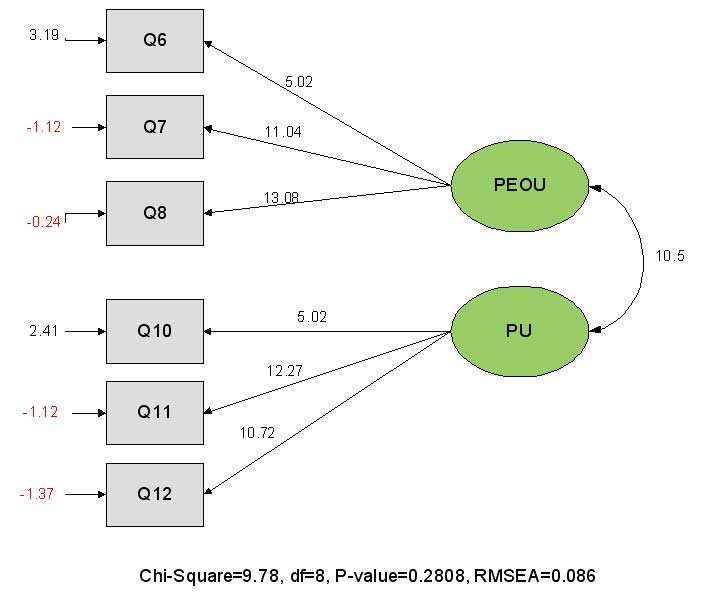

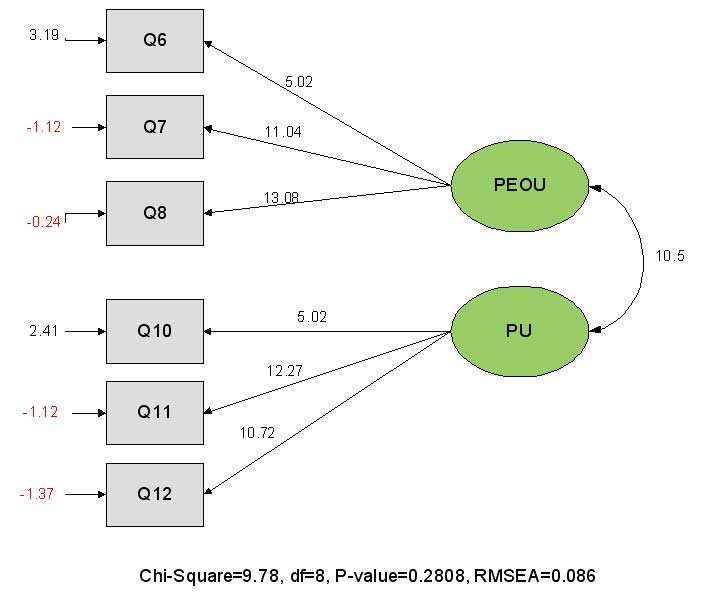

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used in

this study to identify the strength of the

relationships between the variables and their

effect on the latent variables of perceived

usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU).

Figure 2 illustrates the SEM model used in this

study.

All of the variables were

significant with t values well above the critical

value of 2.457 (α=.05, 30df). Additionally, the

goodness of fit statistics for the model indicate

an overall good model. Key goodness of fit indices

include ×2 = 9.78 with a p-value of 0.28 and 8

degrees of freedom, adjusted goodness of fit (AGFI)

= 0.94, and root mean square of approximation (RMSEA)

= 0.086. The model confirms that students (1) view

Remote Proctor as useful for reducing or

discouraging cheating (2) view the system as easy

to set up and use and (3) are supportive of the

system and are willing to adopt Remote Proctor.

Figure 2. Structural equation model

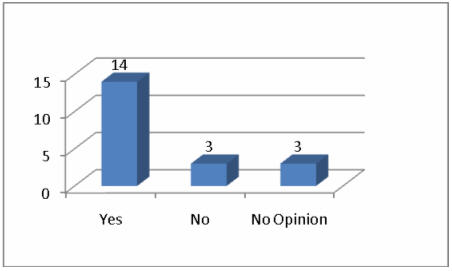

Instructors were more limited in their exposure to

Remote Proctor. Unlike students who were required

to install, configure, and use Remote Proctor,

instructors were only asked to view the videos

captured during the time the tests were taken. Due

to the small sample size (20), SEM could not be

used for analysis. However, instructors supported

adoption at a rate of almost 5:1 (Figure 3).

The results of the pilot study were presented at

the September 2008 Dean’s Council along with a

recommendation to adopt the system. Several of the

members participated in the study and added their

recommendations. The adoption of Remote Proctor

for online testing was approved with a target date

of spring 2009.

Implementation

The academic year for the online program at SSRU

consists of five 8-week terms beginning in mid

August; Fall 1, Fall 2,

Spring 1, Spring 2 and Summer. The decision

to adopt Remote Proctor did not occur until late

in the Fall1 term. Several issues were identified

as critical to successful implementation and

included technological issues as well as student

and faculty issues. A committee was assembled to

address these issues. Committee members consist

of the Director of Information Technology (chair),

Dean of the College of Education (online graduate

degrees), Dean of the

Graduate

School,

Dean of Online Studies, and the Associate Dean of

the

college

of Business.

Figure 3. Faculty recommendation

Technical issues involved interfacing the course

management software (Blackboard) so the Remote

Proctor software would recognize the faculty

assigned to the course. This is necessary so the

faculty member can develop and deploy the Remote

Proctor exams. Also, the bandwidth and storage

requirements for handling the streaming video from

(theoretically) 2500 concurrent exam takers demand

the architecture be highly scalable. There is also

the issue of user support and which campus

office/department will be responsible. SSRU’s

Information Technology (IT) department will

provide helpdesk support from 8:00am to 5:00pm.

Secure Software and IT are in process of testing

the other factors.

Student issues center around two factors:

technical support with installation and

registration (handled by IT) and purchasing the

Remote Proctor. The device is available in the

online bookstore and is used in every online

course offered. All online students are required

to purchase Remote Proctor unless they are within

one term of graduation. This precludes a student

having to spend $180 to take only one or two

tests. Students living near SSRU would be allowed

to come to campus to use Remote Proctor units

available in the Julia Tutwiler Library. Others

are handled on a case by case basis using either

testing centers of live proctors. The Dean’s

Counsel felt it was essential to develop a privacy

use statement to be given to each student.

Faculty issues are associated with monitoring the

saved videos for suspicious activity. While

Software Secure does offer monitoring service, it

is quite expensive due to the number of students

and exams involved.

Once the identified issues were resolved, a date

for implementation was chosen –

Spring 2

students must purchase and begin using Remote

Proctor. Announcements were made on the SSRU

homepage, the main page for each online course,

the course registration page, and in news media (Bathwal

2009).

Unresolved issues

Even though the committee attempted to address the

major issues that arose during implementation,

there are still issues that remain unresolved:

·

Remote Proctor is not yet available for Macintosh

or 64-bit PCs. This is anticipated to be resolved

by fall1-2009;

·

Military students stationed in

Iraq and Afghanistan cannot get Remote Proctor

overseas or attach to a military computer; and

·

Students who need special assistance under the

guidance of the Americans with Disabilities Act

(ADA)

Even though they remain unresolved from a

technology standpoint, Remote Proctor will greatly

reduce the need for human proctors. The company

is working to make available the Macintosh

software as soon as possible, hopefully before the

summer session is over. Military students have

access to commanding officers who are very

familiar with and willing to proctor exams to

enhance the education of their troops. And,

students with disabilities have to be handled in a

manner related to helping them overcome their

particular disability. This would be the case

whether online or in the classroom. For example,

some students simply need more time to take a

test; therefore, a separate test can be made for

them which will allow them to have more time which

other students will not be allowed to access.

Remote Proctor was fully implemented during the

Spring 2 online term,

but not without some minor difficulties. SSRU’s

IT department received some 600 calls for

assistance installing Remote Proctor, several

faculty members needed additional help installing

ExamBuilder software, and some students expressed

concerns about perceive privacy violations. In

spite of the difficulties, Remote Proctor is now

in use in the online program and initial response

by both students and faculty is generally

positive. It seems fair to say that implementing a

project such as this, regardless of proper

planning, is likely to encounter issues. However,

it is anticipated that Remote Proctor will prove

to be another tool to help ensure the quality and

integrity of SSRU’s online program.

Conclusion

In today’s fast-paced, high tech society, the

opportunity to cheat has increased, and research

has shown that, in fact, cheating is on the rise.

Colleges, universities, and accrediting bodies

have become concerned about cheating, especially

in the area of determining whether the student who

registered for a class is actually the one taking

the tests and doing the work in the online

environment. The research presented in this case

study has shown that the Remote Proctor may be a

valuable resource to colleges and universities

when determining that students are actually doing

their own work. Because of its low cost and

functionality, its use will be more cost effective

for students and the university, in the long run.

Faculty and students both feel the device will

help curb cheating.