Introduction

The issue of academic honesty is a sensitive one

for a university because it is so central to the

individual learner’s self-identity, the campus’s

academic mission, the university’s reputation, and

the qualifications it confers. While universities

strive to build learning cultures that support

honest research and teaching, academic integrity

goes beyond the quality of work to the moral fiber

of each generation of learners, and these values

include “honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and

responsibility” (“The Fundamental Values of

Academic Integrity,” 1999, p. 4). Academic

dishonesty has been a persistent part of the

higher education landscape.

Understanding the

potential causes and complexities of academic

dishonesty is critical in building an effective

academic culture and system to try to counter this

phenomenon.

Survey of the Literature

Researchers used meta-analyses of published

research and surveys (with self-reportage by

learners) to get a sense of the scope of this

issue. Studies in both high school and college

reveal an epidemic of academic dishonesty. The

portions of those engaged in academic dishonesty

ranged from 23% to 89% (Miller, Shoptaugh, &

Parkerson, 2008). However, these statistics are

not comparable across time and setting because of

a “substantial disparity in rates being reported

at any one point in time” (Miller, Shoptaugh, &

Parkerson, 2008, pp. 326–327). Ironically,

researchers have also found consistent faculty

underestimation of cheating (Volpe, Davidson, &

Bell,

2008).

Academic Integrity / Academic Misconduct

Academic misconduct involves a range of

behaviors. According to Hughes and McCabe (2006),

misconduct may include the following:

…working on an assignment with others when asked

for individual work, getting questions and answers

from someone who has already taken a test, copying

a few sentences of material without footnoting,

fabricating or falsifying lab data, and receiving

unauthorized help on an assignment (Hughes &

McCabe, 2006, “Academic misconduct…,” p. 1).

Bernardi, Baca, Landers, and Witek (2008), in an

international study, found that students

identified methods of cheatings fairly similarly

in three broad categories: writing, visual / oral

communication, and miscellaneous. The writing

category involved the use of crib notes, writing

notes on the body, and writing on clothing or

other things. The visual aspect involved copying

another’s exam, asking for answers, or having

another student take the exam. The miscellaneous

group involved the programming of calculators,

using cell phones, and hiding notes or books in

the bathroom.

Researchers have listed more nuanced forms of

academic dishonesty in a survey to see how people

perceive this issue. This list includes such

issues as “watching videotaped films of famous

works of fiction rather than reading an assigned

book,” (Higbee & Thomas, 2002, p. 42) using an

article only after having read the abstract,

changing laboratory results, switching off going

to lectures and taking notes with friends, and

turning in the same paper for two different

courses.

External and Internal Causal Factors

Causal factors for academic dishonesty may be

separated into (1) external and situational ones,

and (2) internal, developmental ones. Values may

be socially created between peoples and embedded

in a culture. Some values are situationally based

and relativistic. Other values may be internal to

individuals and may be a factor of their

developmental stages.

(1) External and Situational Causal Factors

In recent years, there have been some studies that

have focused on academic dishonesty in more

international settings. One identified the

influence of culture on academic integrity

(McCabe, Feghali, & Abdallah, 2008). Some

researchers find cheating more endemic in

collectivist cultures, while others find more

challenges in individualistic ones. “‘Instrumental

communities create an ‘egocentric climate’ in

which an ‘individual conscience takes precedence

over the claims of the community’ (Kaplan & Mable,

1998, p. 24) and exacerbate and complicate the

tasks of reinforcing academic integrity on

campuses” (Gallant & Drinan, 2006, p. 847).

External factors related to competition affect

academic dishonesty. These may include pressures

to achieve good grades, test anxiety, the

classroom environment and relative risk of

detection, institutional policies on academic

honesty, and performance and achievement issues (Higbee

& Thomas, 2002). Others suggest that such

situational factors as “the pressure to succeed in

school, external work commitments, heavy course

loads, and financial aid or scholarship

requirements” (Carpenter, Harding, Finelli,

Montgomery & Passow, July 2006, p. 182) have

little effect on academic dishonesty.

The challenges of academic dishonesty do not only

apply to undergraduate students, but

doctoral-level researchers may be poorly advised

and may have insufficient experience in the domain

field. If students plagiarize outside their Ph.D.

advisors’ own area of expertise, lapses may not be

easily discoverable (Mitchell & Carroll, 2008).

Contemporary students may have varying senses of

what is considered cheating. A collaborative

student culture may clash with “a more

traditional, individualistic faculty culture”

(Hughes & McCabe, 2006, “Academic misconduct…,” p.

15). Students read their environments and decide

how to proceed. In a cost-benefit assessment, if

they see a situation as low-risk, they may engage

in academic dishonesty; a majority will choose not

to report their peers even if it is an

institutional requirement (Jendrek, 1992). A

so-called thick trust culture will also result in

the low levels of reporting friends because

loyalty trumps an honor policy. A contextual

approach to e-learning uses organizational theory

to situate “the student cheating problem in the

context of the educational institution as a

complex organization affected by people, time, and

social forces”

(Gallant & Drinan, 2006, p. 841).

(2) Internal, Developmental Causal Factors

In terms of internal factors, Angell (2006) found

some potential links to personality constructs.

Demographic factors do not apparently affect

whether or not a student will engage in academic

misconduct, with researchers finding little or no

correlation between academic dishonesty and

ethnicity, or academic dishonesty and religious

beliefs. Those with higher grade point averages

(GPAs) tend to be less likely to cheat. Older,

non-traditional students tend to cheat less than

their younger counterparts. Those involved in

campus organizations like the Greek system and

athletic teams are more likely to cheat than their

peers (Carpenter, Harding, Finelli, Montgomery &

Passow, 2006). Those with membership in Greek

organizations have a greater likelihood to

fabricate sources (Eberhardt, Rice & Smith,

2003). Students may not have internalized the

various sources of professional ethics for the

different domain fields.

Some internal risk factors relate to study skills:

“poor time management, lack of preparation, lack

of skills to find resources, unwillingness to

follow recommended good practice, inability to

seek appropriate help, (and) low intrinsic

interest in subject” (Sheard, Carbone, & Dick,

2002, n.p.). Traditional university-age students

are seen as not “self-authorized” because of the

particular stage in their intellectual

development.

If students do not feel that they can

generate their own knowledge, then they might

believe that it would be redundant to cite

knowledge sources or to promise to refrain

from accepting assistance on papers and

examinations. When the environment is

populated by individuals who are at the same

developmental stage, it can ‘lead to the

construction and reproduction of certain 'social

realities' in a student culture that define[s]

cheating as more acceptable or less-serious

misconduct than it was considered previously’

(Payne & Nantz, 1994, p. 91, as cited in

Gallant & Drinan,

2006, pp. 843-844).

The greater the level of self-restraint, the lower

the level of acceptance of cheating and cheating

behaviors (Jensen, Arnett, Feldman, & Cauffman,

2001 / 2002). There may be internal reasons for

not cheating, including: “pride in your work, want

to know what your work is worth, can get good

marks without cheating” (Sheard, Carbone, & Dick,

2002, n.p.). The student development theory

focuses on individual student development as a

factor in academic dishonesty.

A consensus view is that cheating will never be

absolutely eradicated either in face-to-face

courses or online ones, including potential

situations where students may pay another to take

the whole course in their stead

(Sibbernsen,

2008-2009). However, there are ways to lessen

this possibility.

Technology and Academic Dishonesty

The role of technology has been controversial in

terms of effects on academic honesty. Some have

linked the popularity of the Internet and Web to

growing “e-cheating” via misuse of the WWW

(Rogers, 2006). Web-based distance education may

be more conducive to academic dishonesty than

face-to-face (F2F) instruction (Kennedy, Nowak,

Thomas, & Davis, 2000, as cited in Baron & Crooks,

2005). A large technological divide exists

between the current generation of students and

those in the professoriate (Windham, 2005). This

gap may mean more opportunities to engage in

academic dishonesty without discovery.

Technologically based online environments may also

be designed to lessen academic dishonesty. Some

testing systems have built-in “misuse detection”

or “plagiarism detection.” Others use computer

forensics to track student work. Some use key

logger spyware and sniffers (Laubscher, Olivier,

Venter, Eloff & Rabe, 2005) to detect academic

dishonesty; others use watermarking to discover

the actual audit trails of exchanged code in a

computer coding course (Daly & Horgan, 2005).

Institutional Interventions

Universities will need to more clearly explain the

rationale for promoting academic honesty and

integrity in lab or research work. Many argue

that this critical value needs to be supported

from the top with its “authoritative allocation”

“at the level of presidents, boards, and

accrediting associations” (Gallant & Drinan, 2006,

p. 855). Leaders need to bring in all elements on

campus to align behind the academic integrity

policy, to avoid some of the blame-shifting that

may occur regarding academic dishonesty (McCabe,

2005). A holistic institutional approach

(MacDonald & Carroll, 2006) may be most

effective. Faculty need to be supported when they

uphold the honor code.

Universities with honor codes have been found to

have lower incidences of cheating (24% of students

report cheating vs. 47% in schools without honor

codes), but McCabe suggests that it’s the student

culture and university prioritizing of academic

honesty, and not the honor code itself that deters

cheating (McCabe, 2005). Melendez (1985) as cited

in McCabe, Trevino, and Butterfield (2002) and

Kidwell (2001), explains a “true honor code”

school as one having the following: a campus

pledge against academic dishonesty, a judicial

board with student input and/or student

leadership, unproctored exams, and a requirement

for reporting. McCabe, et.al (2002) noted that

true honor codes are traditionally located in

small, private institutions with few exceptions,

notably The University of Virginia. The modified

honor code is one way a larger institution can

still promote and hold students accountable to

concerns of academic integrity. The modified

honor code has both (1) communication of

importance of academic integrity and (2) student

involvement in decision making body regarding

academic integrity (McCabe, et al, 2002). The

“modified” honor codes have supported student

decision-making and leadership in setting higher

ethical standards (McCabe, 2005. Peer feedback is

critical to dissuade others from academic

dishonesty (Broeckelman-Post, 2008).

To be effective, the social norms intervention

requires “consistency, depth, and breadth” (Engler,

Landau, & Epstein, 2008, p. 101). These norms

relate to core values of the community (Carpenter,

Harding, Finelli, & Mayhew, 2005). “Notions of

independent thinking, intellectual property, the

struggle of original thought, and academic freedom

are all at risk should dishonesty prevail over

integrity,” (Gallant & Drinan, 2006, p. 853) warn

researchers. Widespread abuses of academic

integrity may lead to endemic corruption

(Crittenden, Hanna, & Peterson, 2009). At

universities, a reputation for poor academic

honesty will dilute degrees and potentially

threaten accreditation.

Faculty members play an important role in a

university’s academic integrity policy. McCabe

and Pavela (2004) offer the foundational

Ten Principles of Academic Integrity. There

is also “an apparent discrepancy in faculty’s

general stated discouragement of cheating and

their actual involvement in its limitation”

(Volpe, Davidson, & Bell, 2008, p. 164). Their

in-class behaviors may discourage a serious

approach to academic honesty.

…20% of faculty in Graham et al. reported that

they did not watch students while they were taking

a test, and 26% of faculty had no syllabus

statements regarding cheating. Furthermore, even

though 79% of faculty reported having caught a

student cheating, only 9% reported penalizing the

student (Volpe, Davidson, & Bell, 2008, p. 165).

Learners may be receiving conflicting messages

about this issue unless faculty are brought on

board. By contrast, some suggest that faculty

members should not maintain a “suspicious

attitude” towards learners because that breaks the

fragile trust necessary in the learning

relationship and introduces disunity (Zwagerman,

2008, p. 677).

How faculty members design assignments affects

learner integrity. One approach is to vary

assignments and assessments between terms.

Another is to avoid penalizing students for

getting unexpected laboratory or research

results. The institution also needs to provide

the proper equipment to fulfill the work, so

students do not compensate for poor equipment by

falsifying results (Hughes & McCabe, 2006,

“Academic misconduct…”). Assignments need to be

more interesting to encourage student

participation (Ma, Wan & Lu, 2008). Encouraging

group collaborations may encourage more academic

honesty (Mercuri, 1998). Curricula built with

progressively more difficult designs and the

building of scaffolding to support and enable the

learning may discourage academic dishonesty

(Linder, Abbott & Fromberger, 2006).

Faculty need to build communities where “the

learning is emphasized over measures of academic

achievement” and where role models who “do not cut

corners” are lauded (Tanner, 2004, p. 292).

Learners need to be inoculated against

pro-plagiarism justifications through rational and

cognitive reasons to build up attitudinal

resistance (Compton & Pfau, 2008). Researchers

have pointed out people’s ability to both engage

in academic dishonesty but still consider

themselves honest people (Mazar, Amir, & Ariely,

2008).

Pedagogical Theories

Since the implementation of the Honor System in

1999, Honor System staff members have emphasized a

student development perspective in adjudicating

those found in violation of the Honor Pledge.

Several studies have determined that becoming more

congruous in integrity is one of several

developmental tasks of college students (Kohlberg,

1984; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991; Perry, 1968;

Rest & Narvaez, 1994). Those associated with the

Honor System are therefore committed to using

procedures and sanctions that are educational in

nature. Staff members strongly believe that

college students are still developing in what it

means to make ethical decisions in times of

dilemmas (whether or not to cheat). They also

believe that character development (becoming more

honest) does not stop when young adults leave

home. On the contrary, many college students learn

what it means to be a good person and a good

citizen through liberal education (in the

old-fashioned definition) and in projects such as

service learning.

When young adults learn that it's not all about

ME, they come to understand that living in a

community requires following certain rules and

regulations for the betterment of the community

itself. Sometimes, young adults away from home

need to learn (from the guidance of those more

experienced) that it's about YOU and ME, together

(Kansas State Honor and Integrity System, 2008,

n.p.).

Chickering’s (1969) theory of identity development

is a psychosocial theory; however it is most

commonly held as the key student development

theory. Chickering’s seven vectors of development

are a series of tasks that students often go

through. Chickering’s non-sequential vectors do

build upon another as students examine and

develop. The seven vectors are as follows:

developing competence, managing emotions, moving

through autonomy to interdependence, developing

mature interpersonal relationships, establishing

identity, developing purpose, and developing

integrity.

Although all vectors work together for a complete

individual, the seventh vector, developing

integrity, relates directly to an honor council

and honor system. The goal for this vector is for

the student to develop congruence between their

moral thoughts and their actions. The student

begins to demonstrate a mutual respect of oneself

and others while incorporating appropriate ethical

decision making strategies into daily life.

With Chickering’s development of integrity,

college students are also seeking to develop

reasoning for moral judgment and decision making.

As ethics, integrity, and moral reasoning are

often intertwined, the theories of Kohlberg (1986)

and Gilligan (1977) focus on modes of reasoning.

Although Gilligan focused her research on women,

the overall moral development models of both

theorists resemble one another. Kohlberg (1986)

stated that decisions (especially in males) were

made though a justice model, searching for what is

just and right while Gilligan (1977) looking at

females explained that the decision making process

includes a level of care for oneself and others.

Although both males and females can use care and

justice in the decision making, men and women

align more often to justice and care

respectively. For men and women, there is a

standard sequence for decision making. In the

first stage, individuals focus on themselves

first. Decisions are based on how an outcome will

affect the individual. The second stage in when

the individual begins to think of others. For

woman in particular, the individual might

sacrifice what is best for himself in order to

enhance another person. The final stage is an

attempt to reach is a balance between oneself and

others. The interdependence of the outcomes of a

decision affecting both oneself and the community

one is in allows the individual to make

appropriate decisions even in an ethical dilemma.

As a student determines how to connect himself or

herself to the community in decision making,

Kitchener (1985) gives five guidelines for an

ethical decision. These five guidelines give

structure to an Honor and Integrity System to be

fair and honest with all involved and help them to

make decisions in the future. The five guidelines

are as follows: Respecting Autonomy (understanding

that what one person might do may not be the

appropriate decision for all), Doing No Harm

(understanding the necessity to cause not extra

harm to others because of one’s decision),

Benefiting Others (understanding in what ways a

decision can be of benefit to another), Being Just

(asking oneself if the decision being made if fair

and just to those involved), and Being Faithful

(asking oneself if they are being faithful to the

ideals, people, and morals that one holds dear).

Background

The Honor and Integrity System

In Fall 1994, Kansas State Provost James Coffman

convened the Provost’s Task Force for Academic

Honesty with a charge to create policies and

guidelines to enhance academic integrity at Kansas

State. By 1996, a draft for the Kansas State

Honor System was in place. Within this draft,

authors Dr. Mitchell D. Strauss and Brad Finkeldei

(Student Body Vice President) compiled the

overarching ideas of the current honor pledge.

These ideas included:

That, as K-State students, they will not give or

receive aid in examinations; that they will not

give or receive non permitted aid in class work,

in the preparation of reports or in any other work

that is to be used by the instructor as the basis

of grading. That, as K-State students, they will

do their share and take an active part in seeing

to it that others as well as themselves uphold the

spirit and letter of the Honor System. This

includes reporting an observed dishonesty. That,

the faculty, on its part, manifests its confidence

in the honor of its students by refraining from

taking unusual and unreasonable precautions to

prevent the forms of dishonesty mentioned above.

The faculty will attempt to avoid academic

procedures that create temptations to violate the

Honor Pledge. On all course work, assignments, or

examinations done by students at Kansas State

University, the following Honor Pledge is either

required or implied: ‘On my honor as a student, I

have neither given nor received unauthorized aid

on this academic work’ (Kansas State Honor and

Integrity System, 2008, n.p.).

Kansas State Student Senate approved the proposed

modified honor code system on December 4, 1997,

and Faculty Senate followed in the same suit on

April 4, 1998. Through the 1998-1999 academic

year, Honor Council appointees constructed the

constitution and by-laws for the Honor System. In

February 2004, this constitution was amended to

include graduate students within the honor

pledge. The motto for this system soon became

“Education, Consultation, Mediation, Adjudication:

We do it ALL with student and faculty development

in mind!” (Kansas

State Honor and Integrity System, 2008, n.p.).

To date, 836 cases have been filed with the

K-State Honor and Integrity System representing

over 1100 students (Kansas State Honor and

Integrity System, 2008). Faculty, staff, and other

students can submit a violation report to the

office regarding academic dishonesty. As faculty

and staff have the autonomy to decide to report,

they too have the autonomy to decide upon a

sanction for the student. The

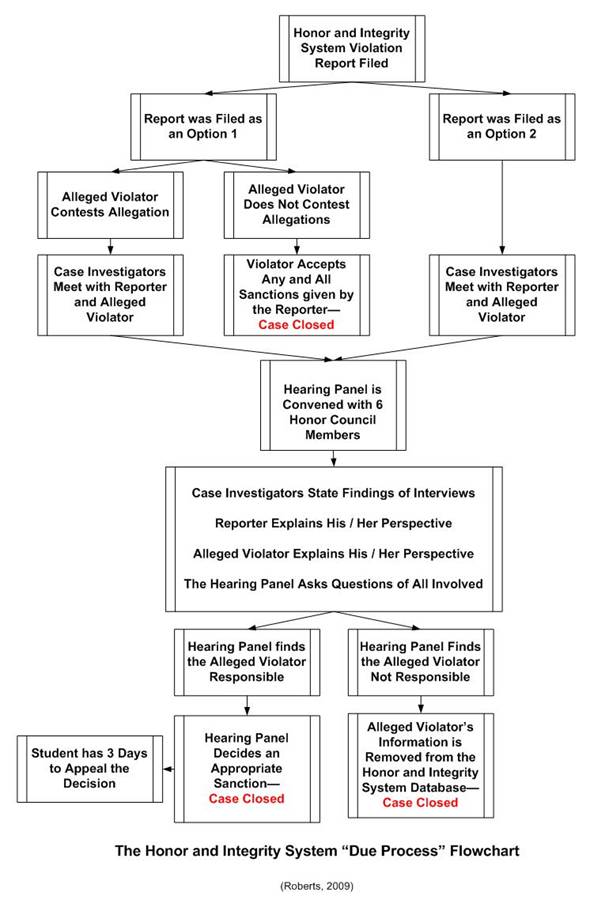

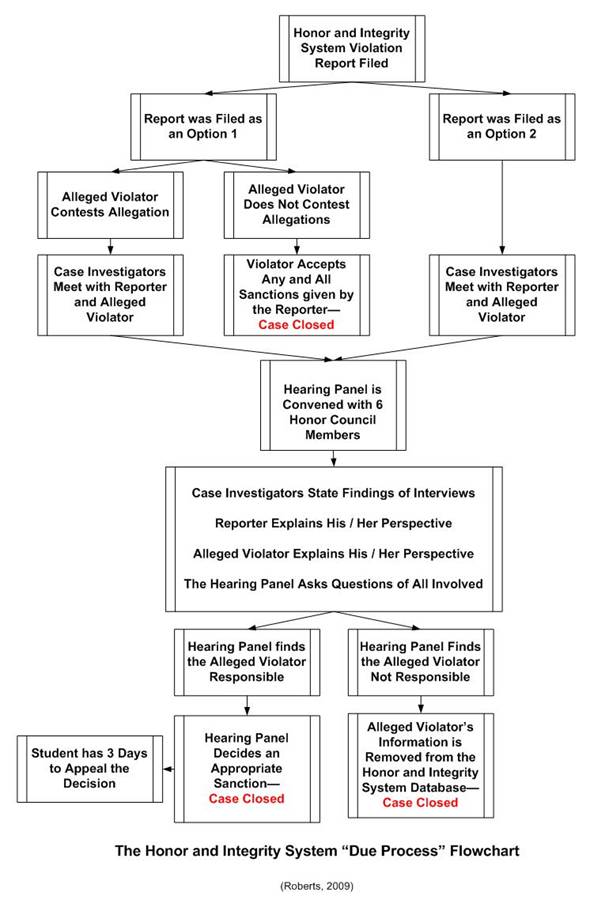

step-by-step process

that an alleged violator follows is one of due

process to the student. The student has the right

to contest an allegation; however, one cannot

contest the sanction. The flowchart below (Fig.

1) follows an Honor and Integrity System report

from being filed until closing the case.

Figure 1: The Honor and Integrity System “Due

Process” Flowchart

(Roberts, personal communication,

February 20, 2009)

Since its inception, the Kansas State Honor and

Integrity System reports have ranged from minor

offenses such as having a fellow classmate sign an

attendance sheet for another to major offenses

which could include law enforcement officials

through breaking and entering to gain test

material or bribery for an increased grade. As

previously mentioned, faculty and staff reporters

may determine a sanction for the alleged

violator. In determining an appropriate sanction,

the Honor and Integrity System suggests that the

reporter and hearing panel establish the level of

truthfulness of the alleged violator through the

process, the premeditation of the act that

violated the honor pledge, and the flagrancy or

severity of the act. These three components can

assist in determining the severity of a sanction

from a warning to possibly suspension or expulsion

from the university. One well known punitive

sanction for students is reception of an “XF” for

the course of violation which signifies on the

student’s transcript that the student has failed

this class due to academic dishonesty. Although

well known, the “XF” is no longer the standard

sanction. Based upon the focus of student

development and education, the most common

sanction for a student is currently the

Development and Integrity course.

The Development and Integrity Course

Following the inception of the Honor and Integrity

System in 1999, the honor council saw a need for a

way of removal of the “X” from an “XF” grade as

well as a way to educate students though the honor

violation sanction. In November of 1999, the

department of Counseling and Educational

Psychology submitted a proposal for an “Academic

Integrity (AI) Seminar.” This seminar is now

entitled the Development and Integrity Class

(worth 1-credit) and it is still housed in the

Department of Special Education, Counseling, and

Student Affairs (formerly Counseling and

Educational Psychology). The first AI seminar

occurred between April and June of 2000 with four

individuals. Each year, the course has emerged as

an educational tool for the Honor and Integrity

System to assist violators of the honor pledge in

understanding the choices he/she makes, academic

integrity at the university setting, professional

standards and integrity in the workplace, and

understanding the ethical and moral development of

college students. The table shown in Fig. 2

relates the number of students who have enrolled

in the Development and Integrity Course.

|

Academic Year |

Face-to-Face Course |

Online Course |

|

Spring 2000 |

4 |

N/A |

|

2000-2001 |

21 |

N/A |

|

2001-2002 |

45 |

N/A |

|

2002-2003 |

100 |

N/A |

|

2003-2004 |

76 |

N/A |

|

2004-2005 |

90 |

N/A |

|

2005-2006 |

77 |

N/A |

|

2006-2007 |

97 |

N/A |

|

2007-2008 |

74 |

11 (Spring only) |

|

2008-2009 (to date) |

60 |

15 |

Figure 2: Table

of Enrollments in Development and Integrity

The Development and Integrity Course (Online)

The need for an online version of the “Development

and Integrity” course originated with a growing

number of students finish their studies and move

on to pursue work and other endeavors but who

still need to take this course in order to fulfill

sanctions or remove an “X”. A Principled

Course Build

Early on, the lead instructor for this course (who

was also serving as the Associate Director of the

Honor and Integrity System) and the instructional

designer decided to take a fully principled

approach to the building of the online version.

This would mean that they would pursue copyright

releases on all contents created. Any video

captured of students would be by their express

consent, and the videographer would not capture

any faces or identifiable information during the

classes to protect their privacy. Students in the

class were also referred to by acronyms or assumed

names to protect their sense of privacy. The

course ran for five weeks and was based on the

following topical modules:

Module 1: Student Development

Module 2: Academic Integrity

Module 3: Giving Credit

Module 4: Ethical Approaches and Decisions

Module 5: Refocusing the Future

Each module consisted of a multimedia article that

would feed the learning based on professional

journalistic pieces created by mainstream

broadcast media organizations. The instructor

created slideshows that would be used in

videotaped lectures. The instructor debriefing of

the learned ideas and help students apply them to

their lives. There were case studies used to help

students discuss applied philosophical and

values-based ideas.

Course Objectives

The course objectives enable students to

understand that they are still developing

integrity while in college. They will empathize

with other stakeholders’ perspectives in terms of

academic dishonesty dilemmas, in order to

formulate better decision-making skills while in a

classroom or future profession-based dilemma.

Students will be able to understand several

perspectives in viewing ethical behavior and

appreciate multiple sides to an argument or

situation. Optimally, they will choose not to act

unethically in the future.

More specifically, students will identify the

ethical risks of academic dishonesty and evaluate

their own academic ethical decision making

strategies. Students may adopt different

strategies in ethical decision making, through

reflection and self-monitoring dialogue. They

will increase their awareness of their own moral

agency in everyday situations and be more aware of

their “obligation to help others manage ethical

decision-making” while respecting others’

boundaries.

Module 1: Student Development

The first module creates the framework

understanding of student development as an element

of counseling. The instructor’s videotaped

lecture helps contextualize the course for

learners. The learners meet their instructor, and

they meet each other. The students review the

syllabus. The instructor’s talk is

future-focused, centered on the professions that

the students will be entering upon graduation.

The instructor’s task is not to necessarily dwell

on the sanction but on supporting the students in

developing the necessary skills to function well

into the future. The stated goal is also to help

them graduate without another academic honor

violation at this university. At date of

publication, of the 644 students, 14 have been

found responsible for a second violation after

having been sanctioned the class. This statistic

includes those students who may not have had the

opportunity to complete the class prior to a

second violation.

The instructor engages with the students who talk

about their busy lives—with work, family, and

courses. The instructor empathizes with the

students’ heavy work and then asks students what

grades mean to them, observing the students

identified issues of status and money. There are

values higher than those, the instructor

suggests. The instructor introduces the theories

of

Lawrence Kohlberg in his

Stages of Moral Development. This shows how

people’s various stages of moral judgment affect

the students’ motivations for their actions. The

instructor also introduces

Carol Gilligan’s (1977)

Ethics of Care Model, which also includes

various stages of moral development. The first

assignment familiarizes students with the honor

system as they read about past cases.

Module 2: Academic Integrity

The second module defines academic integrity.

This is defined both in the context of the

“Cheating Crisis in America’s Schools” news story

but also within the context of

Kansas

State University’s honor policy. The instructor

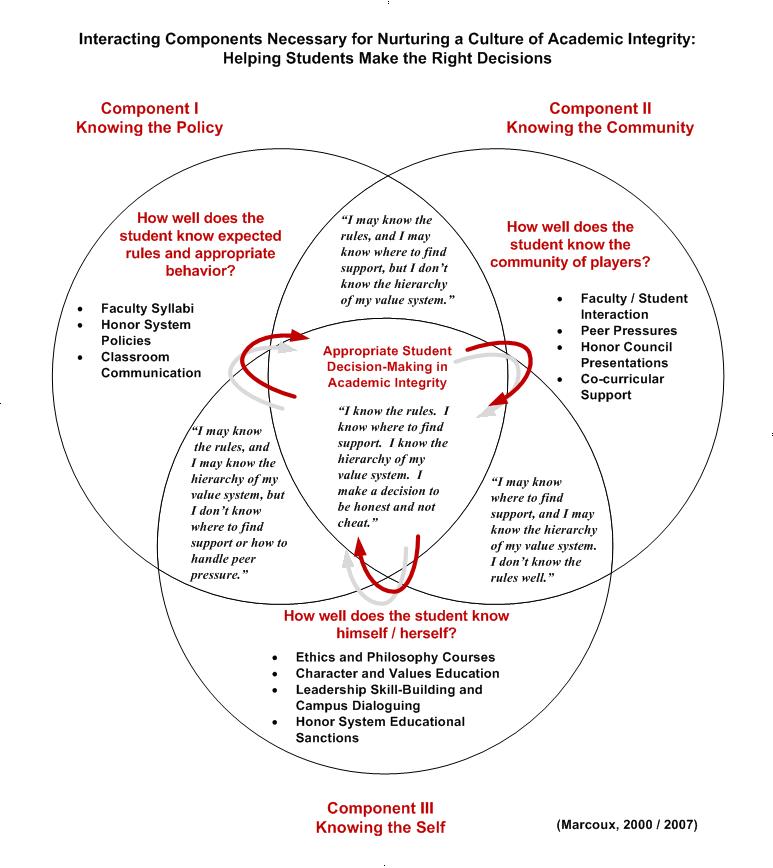

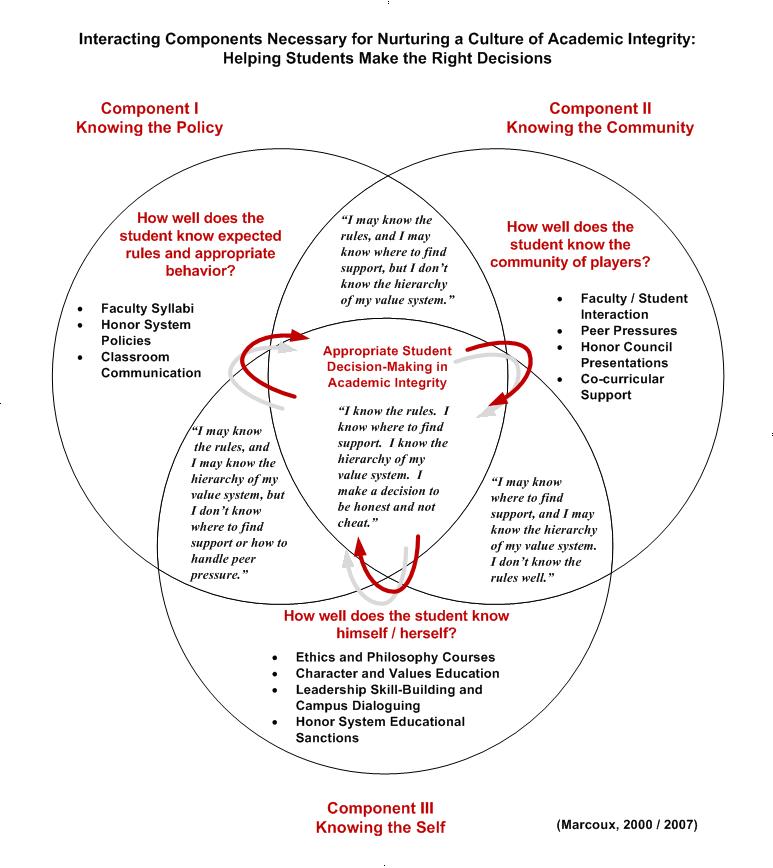

introduces the model for addressing academic

integrity: Component I involves knowing the

policy. Component II involves knowing the

community. Component III involves knowing the

self. Students now have a context for the course

approach.

Figure 3: The K-State Honor System Logo.

Across the top of the logo, it reads “Academic Integrity.”

To the right, it reads “Moral Development.”

And across the bottom, it reads: “The Demands of Citizenship.”

The instructor addresses issues of risky

behaviors—such as taking on excessive life

commitments and pushing deadlines. An “honest

degree” requires honest work, the instructor

exhorts. The instructor walks the students through

understanding the long-term consequences of their

choices: ethical compromises can have effects on

their own lives and that of others. When

individuals get into positions of power and

responsibility in the future, choices will have

many implications on others’ lives, so honesty

will be that much more critical.

A session in Module 2 focuses on students’

experiences, with a focus on the generational

differences between them and the so-called

“gray-hairs” in the academy. The instructor

encourages the group members to share their

experiences that led them to the academic

integrity sanction, working with the students to

understand motivations and actions in the context

of integrity. The students explain how they

forgot to cite sources in a research paper or how

they were under multiple pressures in their lives

and thought plagiarism would be an easy

copy-and-paste solution. Another describes how he

put a grade on a paper before he actually took a

test. Another has had an issue with lab notes.

Dr. Helene Marcoux (personal communication, 2007),

the instructor, exhorts the class about shame:

It is good for you to feel guilt and shame in

moderation. If you don’t have enough guilt and

shame, society hurts. If you have too much, who

hurts? You do. So deal with that guilt. Deal

with that embarrassment. And then let it go.

That’s what this class is about, too. It’s

processing through what happened and letting it go

and doing better the next time around.

As a trained counselor, the instructor is helping

the students work through the emotional fallout of

the students’ experiences while also addressing

community standards and expectations: Even if one

doesn’t agree with these standards, the standards

still have a way of affecting individual lives.

Students write a reflection paper on the honor

pledge violation. Students are asked to summarize

as best they can remember, what the circumstances

were leading to the Honor Pledge

violation/dilemma, what was happening at the time

of the violation/dilemma, what they were thinking

and feeling, and their thoughts and emotions

immediately following the violation/dilemma but

before having a report written. The students also

reflect on when they received notification of the

violation and the hearing process. The paper

concludes with the question of whether the student

has changed any of their thoughts or feelings

regarding the violation since being sanctioned.

Students must also synthesize the information from an

investigative news story about the cheating crisis

in American schools. The students discuss how

teachers (high school) and instructors (colleges

and universities) contribute to or factor into the

issue of academic integrity, its lack or

prevalence. They must decide whether students

should be responsible for addressing academic

dishonesty in the classroom when they see it and

the students must determine whether they believe

promoting integrity is a “lost” cause. As seen in

the news story, many faculty and students have

mistrust between them; therefore, this assignment

concludes with the student offering two or three

suggestions for improving the trust between

faculty members and students.

Figure 4: Interacting Components Necessary for

Nurturing a Culture of Academic Integrity

(Marcoux, 2000/2007;

used by permission of Dr. Helene Marcoux, Feb.

2009)

Module 3: Giving Credit

The third module provides a foundational

understanding about the rationales for giving

credit where it is due to avoid plagiarism. The

instructor draws on the publication “On

Being a Scientist: Responsible Conduct in

Research” (2008) by The National Academies

Press to help students argue through various

professional dilemmas in research. The instructor

uses a “jigsaw” to help them work through the

cases. This lesson involves understandings of

information provenance, primary and secondary

sourcing, and proper citations. This helps

learners connect to the practices in the larger

academic community and professions.

The students study a case of widespread cheating

at a high school in the state and discuss the

complex fallouts on a number of stakeholders—on

the students, the parents, the instructor, the

school board, and the high school as a whole.

Students must make the decision of which side they

support. The students also discuss the idea that

others say that cheating it not wrong but helps

you gain an advantage. The students see through

this real life example how academic dishonesty

among some students can affect those honest

students as well.

Students write a reflection paper on academic

integrity to synthesize the various ideas. Using

the

K-State Honor & Integrity System website,

students are asked to read actual cases

adjudicated at K-State. Students are asked to

summarize the academic integrity cases for a given

year. Based on the students’ research, the

students are asked to make observations and

generalize based on the information found. They

examine violations, sanctions, rank of reporter,

cases that went to a hearing, and are asked to

draw conclusions for the differences in the cases.

Module 4: Ethical Approaches and Decisions

The fourth module focuses on ethical dilemmas in

personal and professional lives. The instructor

shows the effects of student dishonesty in the

experience of one instructor and administrator who

serves as a guest speaker. The instructor also

offers some ethical models, such as T.L. Beauchamp

and J.F. Childress’s model (from Principles of

Biomedical Ethics), and which is added to by

K.S. Kitchener (in Foundations of Ethical

Practice, Research, and Teaching in Psychology).

The instructor also discusses the relevance of I.

Kant’s

categorical imperative as applied to people’s

interests.

The instructor illustrates four approaches to

framing ethical dilemmas: principle-based,

case-based, virtue-based, and responsibility

based. What principle or rule was broken in the

ethical dilemma? What specific case details

surround the dilemma? Who is the person

involved? And whose obligation is it to address

this dilemma? The presentation shows the

strengths and weaknesses of each framework for

ethical decision-making and analysis. Film

snippets shown depict characters in various

situations of professional ethical dilemmas.

Students then write a “retirement” paper about

what they want to have achieved in their lives by

the time they retire. Students are also asked to

ruminate on personal heroes and heroines and what

they admire about them.

Module 5: Refocusing the Future

The final module culminates the learning by

introducing

James Rest’s (1986)

Defining Issues Test, which focuses on moral

development. Using this as a general framework,

students re-conceptualize their academic

violation. Students also have a possible

catharsis in contemplating what they would say to

the faculty member and the student honor council

that sanctioned them.

The multimedia in Module 5 focuses on Michael

Josephson’s poem “What Will Matter” (Josephson,

2009) to offer a more long-term view of life and

personal choices. The professor also links to

lyrics of a song to highlight the role of ethics

in life. The curriculum concludes with a

culminating case about a professor who was found

guilty of murdering two people in his youth; he

served his time and had entered the professoriate.

When his past was discovered, he was removed from

his faculty post. The questions: Was this man

rehabilitated? Should he be allowed to teach and

contribute to society?

As a final paper, students are asked to refocus on

the class and on their violation. After having

spent time examining academic integrity, decision

making, and ethics, the students are asked if they

think they were aware of the ethical/moral nature

of the individual violation. Students reflect on

what the class has meant to them and how they

might think or make decisions differently based on

the class.

Adaptations of the Course since Construction

As a course develops, minor changes and evolution

occur with various instructors and students within

the class. Since the inception of the online

class, the following changes have occurred. The

syllabus

for the current Spring 2009 class is included.

The students do not look at the class in modules,

but rather weeks similar to a face-to-face class.

The five modules are spread through a 10 week

period of time. Each week the new information is

uploaded and unlocked for access for the

students. This includes a PowerPoint

presentation, all needed handouts as well as all

multimedia components. Each week the students are

also asked to answer specific questions or

discussion topics through the online message

board. Following their own original response, the

students are asked to respond to a minimum of two

classmates’ responses for the same week to create

an online dialogue of the week’s information.

An additional component of the class is a week spent on

citations. Although citations are discussed as

giving appropriate credit and through the idea of

sloppy scholarship, many students were unable to

create appropriate citation. Within this week,

students examine correct ways to cite books,

journals, and websites and must complete a

citation exercise which includes creating in-text

citations and reference pages.

Some Lessons Learned

Building an online course to change attitudes,

awareness and behaviors is ambitious. Any of

these elements may be highly entrenched. The

strategy was to engage learners in an interactive

online course. The course was built in a way that

aligned with university standards and policies.

This alignment strengthened the impact of the

course. The Development and Integrity course was

built in a principled way by observing the

intellectual property laws and federal

accessibility guidelines (with full transcription

of all audio and video, alt-testing of images, and

other endeavors).

The course was designed to support learners. It

was designed to offer metacognitive awareness and

some catharsis as they moved through the honor and

integrity process. Students were protected as

they went through the course. The students’ sense

of self, their public identities, and their

self-respect were all protected in the learning

process. The students’ voices were encouraged and

supported in this course. The instructor engaged

with each learner in a way that each was

recognized and affirmed.

The course design instructor clarified that she

would not even be addressing students in the

course by name (unless students spoke to the

instructor first), on the off-chance they didn’t

want to be identified as having any relationship

with the instructor, given the “honor and

integrity” profile on campus.

The use of the multimedia was strategic to include

students in on the national debates relating to

academic integrity. The contents also involved

case studies from a national online repository

(with proper copyright release) to enhance

learners’ ability to ethically reason. The

instructor’s telepresence—in introductory video

snippets and in course videos—was a critical part

of creating rapport and in encouraging the

identification with an instructor modeling honor

and integrity. The instructor has a role model

responsibility in terms of integrity (Lumpkin,

2008).

Students wrote personal analytical essays and

received in-depth responses by the instructor.

This allowed more customized and interactive

assessment. This also allowed the instructor to

promote the various learners’ respective growth

issues individually.

The course was built for transferability with the

separation of components for optimal instructor

flexibility. The course would be designed to be

inheritable by others, so the various components

of the course could be changed in or out depending

on instructor needs. There would be room for

defining domain-specific professional values and

ethics that would inform the learning for

different groups.

Conclusion

As this online course “Development and Integrity”

is taught both online and face-to-face, more

information will be collected to evolve and revise

the course materials. The reality of academic

integrity is a critical one for 21st

century higher education, with much at risk if

universities fail. An online development and

integrity course serves an important function in a

university’s overall approach to academic

integrity by offering opportunities for

rehabilitation and further learning. This course

carries a pro-social and pro-learner orientation

that supports the idea of social responsibilities

and second chances.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. David Allen, Dr. Christy Moran, and

Dr. Ken Hughey in assisting me to take on

instructor responsibilities of the course and

adapt the class to guide the students. - CJR

Thanks to Dr. Helene Marcoux, Rosemary Boggs, and

Dr. David Allen for helping this initial online

course build come together. Thanks to Tim Seley

and Evan Reser for the videography work. Thanks

to R. Max. - SHJ