Introduction

The proliferation of online programs and courses in higher education is considered by many scholars a pervasive societal phenomenon (Heeger, 2007). This remarkable growth can be easily attributed to the technological and societal changes as well as the increased demand for alternate delivery modes of educational offerings (Heeger, 2007). Indeed, according to the Sloan Consortium, in the fall of 2007, almost 4 million students in the US were enrolled in at least one online course, an increase of 12% (or about 450.000 students) compared to the year before. According to one report, more than 96% of the nation’s higher education institutions offer some form of online learning opportunities (Ebersole, 2007) In addition, the Sloan Consortium reports that more than 80% of the Doctoral/Research institutions today offer some sort of coursework online.

The increased availability of online coursework and programs in higher education has had a significant impact in the corporate sector. In today’s technology driven world an increased number of adult learners need training or professional development to further their careers (Meyer, 2002). This need had a significant impact in the culture of the workplace as there is now an increased demand for employees to remain constantly up-to-date in their field as a result of being part of a knowledge-driven society (O’Neil et al, 2004). In order to meet the demand for both professional development and current knowledge in the field, universities developed alternate delivery modes for existing programs, including the online format.

The availability of online course and program offerings constitute the prime example of accessible educational opportunities for current employees. Indeed, distance and online education have been more successful in the corporate world than in academia (Adams & Defleur, 2006). Corporations have successfully promoted online education over the years for the purposes of training and/or continuing education, and certain types of online degrees are considered an acceptable credential within the corporate world (Adams & Defleur, 2006). In light of these developments, it is not surprising that the online education offerings in the US have witnessed a remarkable growth rate during the last five years.

The proliferation of online offerings raises the question of whether the educational quality and learning outcomes of online instruction are similar compared to the face-to-face instruction (Allen et al, 2002; Bernard et al, 2004; Coates, 2004; Fortune et al, 2006; Neuhauser, 2002). The Sloan Consortium indicates that 45% of the chief academic officers surveyed believe that online and face-to-face education methods have similar learning outcomes. Ken Hartman (2007) cites a 2005 survey of human resources representatives according to which more than 62% of employers have a favorable opinion of online instruction; the survey respondents also view e-learning as an equal or superior mode of instruction compared to courses taught face-to-face. However, Adams & Defleur (2006) who also conducted a survey of potential employers found graduates with online degrees are less likely to be hired than applicants who have received their degree through coursework delivered in either a hybrid or face-to-face format.

One critical area for evaluating the effectiveness of online education in the workplace is communication. According to a survey of hiring officers by Peterson (1997), more than 90% of the respondents consider communication to be an essential skill for success in the workplace. However, according to the same survey, interviewers found that only 60% of the applicants demonstrated effective communication skills during the interview, and identified the inadequacy of oral skills as the most prevalent communication inadequacy observed (Peterson, 1997). In general, effective public speaking and interpersonal communication skills are considered by many human resources managers to be essential for prospective employees.

This case study examines student perceptions on a number of variables including effectiveness of delivery, knowledge acquisition, and the rationale for enrolling associated with an online section of a public speaking course. The said course is offered online twice a year at a major research university with a strong online presence in the Eastern United States. The main objectives of the course include the development and delivery of speeches and associated oral communication. In light of the student responses, the study also looks at the instructional challenges associated with teaching such a course in an online setting.

A “Different” Public Speaking Course Online

The research literature does include a few case studies of the traditional public speaking course offered in an online setting. Clark and Jones (2001), conducted a study comparing online and face-to-face sections of a public speaking course in a community college. The authors examined students’ rationale for enrollment as well as student perceptions of communication apprehension and public speaking ability before and after taking the course. The findings indicated that there was no significant difference between the two sections. Nicosia (2005), discusses the successful incorporation of certain assignments of a traditional public speaking course in an online format (such as the initial self-introduction speech). The author further discusses the challenges associated with teaching communication and public speaking courses in an online environment including, the emphasis on the personal interaction and the skills-based acquisition nature of the curriculum which is harder to master in an online setting (Nicosia, 2005).

The versions of the public speaking course discussed above are more closely associated with a hybrid delivery format where part of the course content is delivered online, but some face-to-face interaction is also required especially for the delivery of the speeches. The online version of the traditional public speaking course under examination was developed in 2005. All of the course content was delivered online using the Blackboard interface. The textbooks were the same with some, but not with all of the face-to-face sections. Students in the online section were required to view Powerpoint lectures with audio and participate in discussion boards weekly. The evaluation for the online section also included three quizzes consisting of multiple choice, true-false questions during pre-announced regular intervals within the quarter (weeks 3,6 & 9 of the 10-week quarter system). Students were also required to write, deliver and submit either streaming video online or via VHS/ DVD an informative speech and a persuasive speech (typically the face-to-face section includes a speech of self-introduction in addition to the informative and the persuasive speech). No face-to-face meetings were required. The synchronous conversation and discussion options now available through the Blackboard interface were not used for those sections.

The instructor, who also developed the course, has taught the face-to-face sections in the past, but did not teach the online and face-to-face section during the same quarter. More than 95% of the students enrolled in the online sections of the course were completing their degree on a part-time basis and were considered working adults. Less than 5% of the students were located abroad. It is important to note that the course is offered in a variety of formats in order to accommodate different schedules and preferences. Specifically, students in the institution under examination can take the public speaking course:

- during the day (traditional, full-time students)

- during the evening (meets once a week for 10 weeks/3 hours per session, commuter/working adults/part-time students)

- during Saturday (meets once a week for 6 weeks/4 hours per session, accelerated version/working adults/part-time students)

- online (no face-to-face meetings, weekly assignments/participation required and speeches/quizzes due at regular intervals throughout the quarter/online students)

Based on those options, and assuming the students are able to commute in order to attend the campus section, it can be inferred that students do in fact have at least some choice regarding the delivery options for the course.

Methodology

In order to assess students’ perceptions regarding the effectiveness of the online section of public speaking, a cross-sectional survey was administered in three versions of the online course (Winter 2007, Summer 2007, Winter 2008). In total, four sections of the course (one from Winter and Summer 2007 and two from Winter 2008) were examined. The survey instrument included Likert-scale and true/false questions as well as an open-ended qualitative question regarding the feelings of the students towards the online section of the course (in terms of learning experience and knowledge acquisition, workload and overall recommendation towards the online delivery). The survey also attempted to assess the rationale behind the students’ decisions to enroll in an online section for the specific course. There was also a control question in order to find out whether the respondents are familiar with the different delivery modes of the specific course.

The survey was available during the last week of the quarter and had to be completed entirely online. Student participation was voluntary, but students received between 2.5% (Winter 2007, Summer 2007) and 5% (Winter 2008) bonus in their final grade for participating. The responses to the survey questions were anonymous as there was no way to link survey data to individual students. It is important to note that the survey instrument asked students to make a prediction regarding the face-to-face sections of the said course. The instructor did provide some information regarding the content and delivery of the face-to-face sections of the course (e.g. number of required speeches. In addition, a few students had taken other face-to-face courses in the University in the past. However, the online students in this study did not attend both the face-to-face and online section of the course and thus their responses were based on their expectations of what a face-to-face section is likely to be rather than an actual experience.

Results

Both the quantitative and qualitative responses from the survey clearly indicate that the vast majority of the respondents had a positive and valuable learning experience in the online sections of public speaking. In total, 55 out of 71 students in the four online sections of Public Speaking participated in the survey, a response rate of 77.5%. The results and response rates are consistent across all four sections examined.

Quantitative Findings

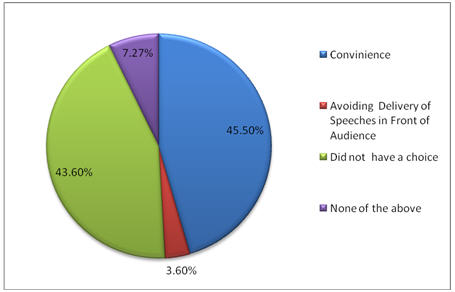

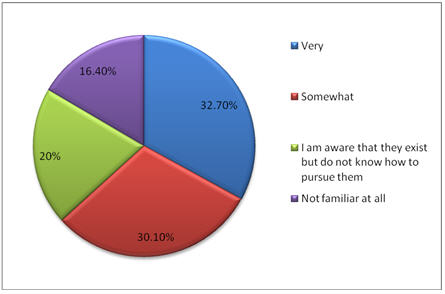

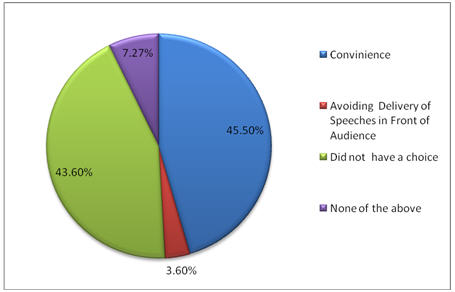

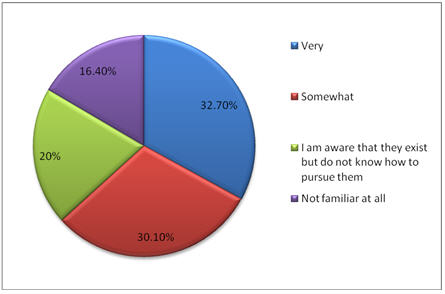

The quantitative results highlight a few crucial findings for the online delivery of the specific course. First, about 63% of the respondents indicated that they are familiar with the different modes of delivery for the specific course (evening, accelerated on Saturday etc) (Figure 1). When asked to indicate the primary reason for opting for the online delivery, respondents are almost equally split between convenience (45%) and their own lack of a real choice (44%) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. What was the primary reason that you chose to take COM 230 online?

Figure 2. How familiar are you with the different deliver modes at the University

(e.g. Saturday, evening, day etc)?

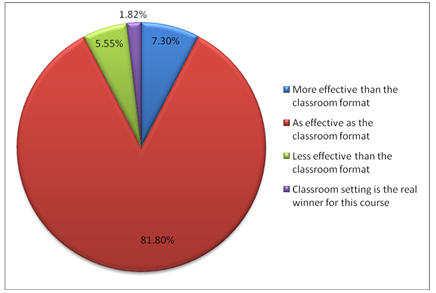

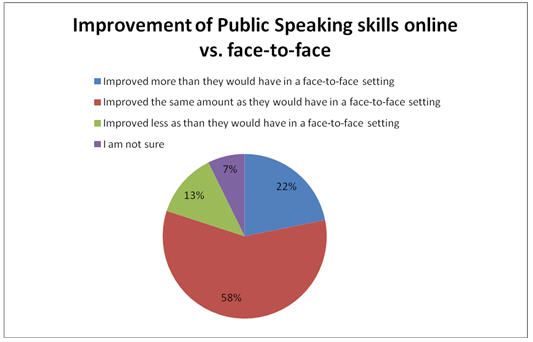

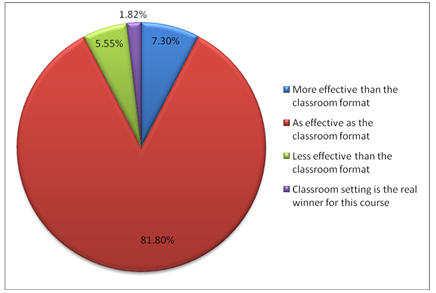

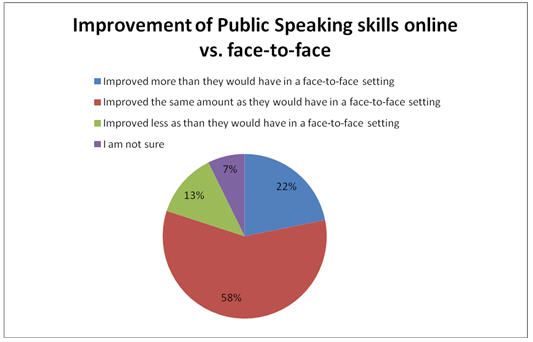

Furthermore, about 80% of the respondents indicated that initially they were at least to some degree concerned with taking a public speaking course in an online setting. However, at the conclusion of the course more than 80% of the students felt the delivery and knowledge acquisition skills from the online version of the course were as effective as they would be in a classroom format (Figure 3). Additionally, 80% of the students felt they learned the same amount in the online version of the course as they would have in a face-to-face format (Figure 4). Finally, 80% of the students indicated that they believe their public speaking skills through the online version of the course developed to the same degree or more than they would have through a face-to-face version (Figure 5).

Figure 3. Based on your experience in COM 230 this quarter would you say that

delivery and knowledge acquisition skills from the online mode are:

Figure 4. Based on your experience in COM 230 do you feel that you learned:

Figure 5. Based on your experience in COM 230 do you feel that your public speaking skills

(including preparation, outlining, delivery etc):

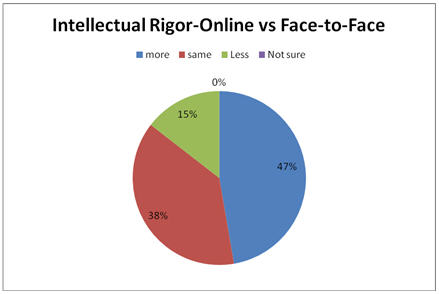

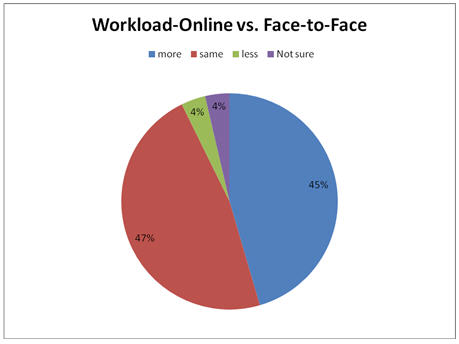

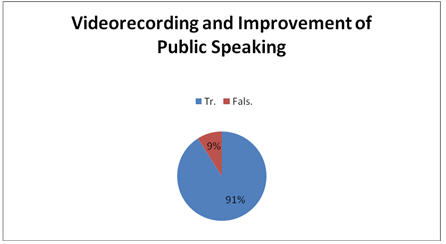

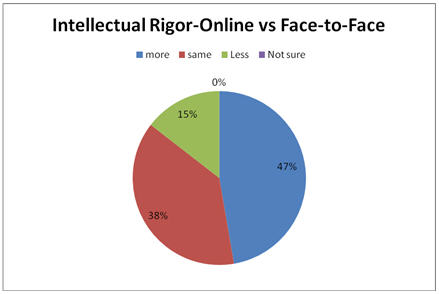

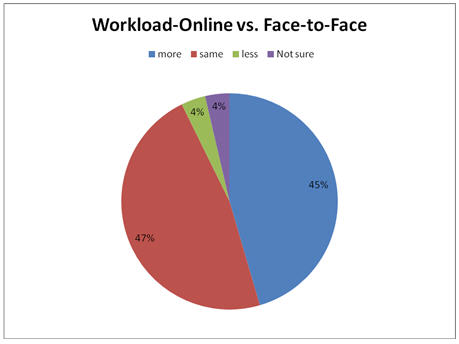

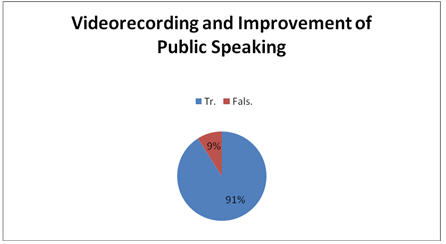

Students were also asked regarding their perceptions of the academic rigor and workload of the online version of the course. Almost half of the respondents (47%) indicated that the online version was more rigorous compared to a face-to-face version (Figure 6). More than 90% of the students felt the workload for the online version was the same or even more compared to a face-to-face version (Figure 7). An overwhelming majority of the students (91%), reported that the video-recording requirement for the speech submission helped them improve and practice the skills covered in the course (Figure 8).

Figure 6. Based on your experience in COM 230, do you feel that the intellectual

rigor compared to a face-to-face course was:

Figure 7. Based on your experience in COM 230, the quantity of the workload and

the time that you spent preparing assignments compared to a face-to-face course was:

Figure 8. The video-recording requirement helps practice and improve on the

public

speaking skills that COM 230 covers:

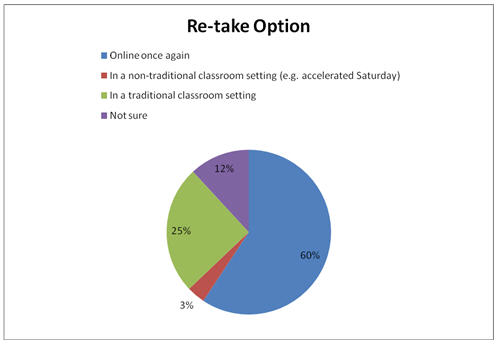

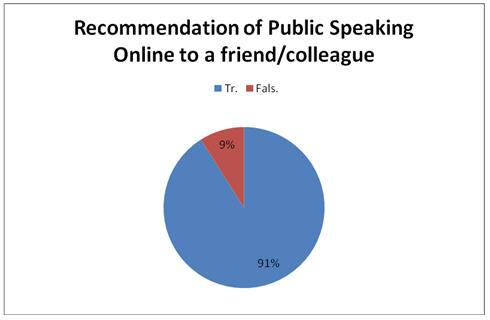

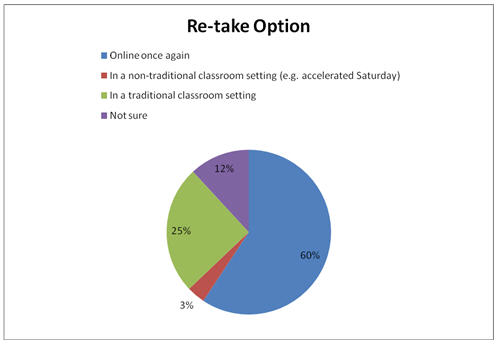

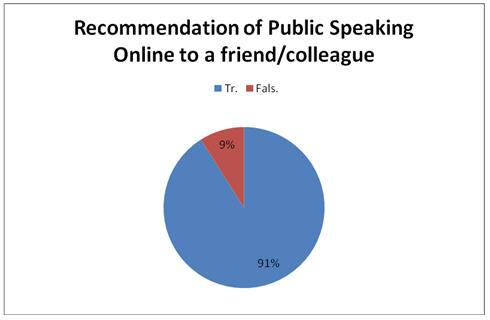

One of the most impressive finding of the survey was the indication that 60% of the respondents would take the course online once again if they were given a second chance (Figure 9). In addition, more than 90% of the respondents would recommend the online version of the course to a colleague or a friend, which is a clear statement regarding student attitudes towards the specific delivery mode (Figure 10).

Figure 9. Assuming you had a choice, and based on your experience from COM 230

online would you take this class:

Figure 10. I would recommend to a friend/colleague the online section of COM 230.

Qualitative Findings

The qualitative responses in the open-ended question of the survey, provided additional insight into the rationale for the quantitative responses given above, but also highlighted the challenges associated with taking and teaching the specific section in an online format. A few themes are evident through the qualitative commentary. First, many students felt the online version of the course was equally or more effective compared to a face-to-face version, despite some initial concerns. A few students enjoyed the convenience of the online format, the skills learned, as well as the rigor of the course as reflected in the comments below:

“I really enjoyed this class I think it was great way for me to take this course without having to the college and I believe I gained many important skills that I will use later in my teaching career. I was not good at giving speeches and after this class I feel like I have a step towards learning how to give speeches well. I enjoyed the class and I would definitely recommend it to friends”.

“ I feel like I really learned a lot in this class. I actually felt like i had to prepare more in an online setting than a class speech. For instance, you cant watch other peoples speeches before you go, as you can in a class. I used to watch people and use what they did to help my speech sometimes in order to not make certain mistakes etc. I felt that from reading the book and listening online, as well as watching the speeches on video for class I was very well prepared. There were certain challenges of course being an online class, such as recording the tape etc. but it was really a fun course and I loved the online discussion. thanks so much for a great quarter…”.

Some students, emphasized the overall effectiveness of the course and the possible advantages of the online format:

“Although I was skeptical about how effective an on-line speaking course would be, I was pleasantly surprised. In my experience, most public speaking courses focus on the presentation itself. This course did that, but also taught skills in speech writing, listening skills, ethical obligations, and presenting information logically. This was of great value to me. In addition, the professor was the only one who had to spend the time viewing all of the speeches, so we got ten solid weeks of education. In a typical classroom setting, students usually sit through all of the presentations which consumes a lot of time. Overall, this was an excellent experience. I take with me new skills and tools that will definitely be put to use in my professional and personal life.”

In addition to the advantages of taking a public speaking course online, students also indicated several challenges associated with the specific delivery format. The main student criticism focused on the recording requirement for the speeches as well as the lack of a live audience during the speech delivery. Below are four comments highlighting the difficulties associated with the technical requirements and the absence of a live audience associated with the online version of the course under examination:

“I had more problems getting my speech recorded and burned onto a usable format then anything else, and I don't think the added stress should be added to the course load. I think in a face-to-face, we could have started with smaller speeches and done them more frequently to help build confidence. I'm a pretty good speaker (I do training and presentations quite often at work), but getting in front of a camera was a nightmare. It was even worse that a camera gives you the ability to start over, as it made both of the ten minute speeches into two hour ordeals. I liked the class, and the course work was informative, but I'm not sure I like the online format for this type of class”.

“ I believe that part of the speech giving anxiety is performing in front of an audience. Online does not provide that level of experience that a real classroom would.”

“The technical requirements are very stringent and frustrating and I feel it unnecessarily compounds the stress of presenting the speech itself. The required visual aid would be much easier to institute in a face-to-face setting but becomes a huge hindrance in the online setting.”

“The content of the course was effective with respect to the readings and discussion. However presenting in front of a camera is challenging at best because its unresponsive. The camera also makes me more nervous because it seems to amplify any strange presentation problems (not looking at the camera, ticks, pauses, etc).Just having to know that i will have to sit and watch it to make sure it looks solid before sending makes me feel awkward. Also I think this is a class that I could have benefited from the normal classroom banter regarding course material and problems with speaking in public in general. This could have been a disaster if the professor wasn’t as involved or organized”.

Discussion

A few key findings emerge from the survey results. First, the majority of the students felt they received a comparable educational experience in terms of academic rigor and skills from the online version of the course as they would have with a face-to-face section. While results indicate the online version of the course does pose some challenges in regards to the submission of the speeches, an overwhelming majority of the students believe that the requirement to videotape and submit the speeches for evaluation did help master the oral communication skills covered in the course. The fact that students had the ability to review their speech prior to submission and get a sense on how they look on camera can be classified as one of the benefits of the online delivery of the specific course. While some face-to-face sections involve the recording of the speeches delivered in the classroom, this method only allows the evaluation of the speech after it has been delivered and graded.

Overall, despite the challenges associated with taking the online version of the course three key findings from the survey highlight that a fully online version of a public speaking course can work effectively. First, an overwhelming majority of the students believe they learned the same or more than they would have in the face-to-face version. Second, a large percentage of the students would re-take the online version of the course if they had a second chance. Third, an overwhelming majority of the students would recommend the online version to a friend/colleague.

The technical requirements associated with the delivery of the speeches do present a challenge from both a student and instructional perspective. In the version of the course under examination, students had to record the speech assignments, and successfully convert the video to a DVD/VHS or upload it to a streaming server online. All of those options require specific hardware and software that students need to be able to use. There is always the risk of a decline of the video and audio quality, thus preventing the instructor from fully appreciating and adequately evaluating the speech; this was a common problem in the sections examined, affecting at least 15% of the submissions. In addition, while explicitly cautioned not to register for the online version unless they can meet one of the submission options, recently (Winter 2008) there has been an increase of the number of submissions that do not conform to the submission requirements (about 20% of the submissions received). The submissions which do not conform to the established requirements present another instructional challenge; assuming the instructor wants to give the students the benefit of the doubt an effort has to be made to either view the submissions that do not meet the format requirements or to work with the specific students for a re-submission that conforms to the course requirements.

Another challenge with the online version of the course that was used in this study was the lack of a live audience for the delivery of the speeches. While students were encouraged to record their speeches in front of a live audience that they setup themselves (for bonus points in the speech), very few students (less than 5% of submissions) make use of this option. This can be attributed to the difficulties associated with getting a live audience (time requirement, room location etc) and the additional challenge of capturing the audience’s reactions in the recording.

In light of the findings above, the following solutions have been implemented in the current version of the online public speaking course. First, students are required to record their speeches in front of an audience of at least three adults (the audience must be evident during at least part of the recording). Second, the current version of the online section uses two relatively new communication features of the Blackboard interface; voice boards (allowing for audio discussion posts) and ‘live classroom’ where students are able to log in at the same time with both audio and video and interact with the fellow classmates and the instructor. Those features allow for increased interaction among the group members. The ‘live classroom’ feature is also used as a forum for delivering the speeches and therefore provides the live audience setting which is the standard in a speech course. The ‘ Wimba live classroom’ software may also be used for recording the speeches asynchronously (in the presence of an audience) thus allowing students to directly upload their speeches on Blackboard. However, the ‘live classroom’ option means additional work for the instructor as sessions have to be held more than once to accommodate the different schedules of the online learners.

Finally, the time devoted to the teaching of the online public speaking section should be considered. The total time spent on the actual instruction and preparation of the online section (2 hours average per week) was less than the face-to-face version (5 hours on average per week). However, grading and dealing with student questions and complaints was considerably more time consuming in the online version (5 hours on average per week) than in the face-to-face version (2 hours on average per week). It should also be noted that developing and updating the online section of the course requires on average 10 hours per week, though this is only applicable on the quarters the course is updated or developed.

Conclusion, Limitations and Future Research

This paper includes results of a comprehensive survey of students enrolled in a public speaking course delivered entirely online. The survey results clearly indicate that a fully online version of a public speaking course can be comparable to a face-to-face version in terms of skills, knowledge acquisition, workload and academic rigor. In addition, the results indicate the students surveyed were satisfied from the online version of the course and would re-take it if they were given a chance. However, it is clear that the online version of the public speaking course is best suited to the students who are familiar with video recordings and the online environment. The convenience associated with the opportunity of taking the specific course online seems to the main driving force behind the choice of taking the specific course in an online environment. The above findings indicate that the online version of the public speaking course is especially appealing to working adults who would like to improve their oral communication skills without having to worry about attending a class at a specific time slot. The technical challenges and the lack of audience interaction, two issues the survey respondents indicated as drawbacks of the online version are currently addressed to at least some degree by using the new technologies of the Blackboard interface.

This article analyzed the responses and their implications from the students who enrolled in the online sections of the public speaking course during the selected time frame. Due to the selection of the specific sample, caution should be exercised in generalizing the results beyond the specific population. Further research is needed in identifying the perceptions of online students towards skills-based courses like public speaking. One aspect that warrants further attention is whether certain types of courses such as public speaking are appealing in an online setting due to the perception that interaction with the classmates will be limited (thus making it more comfortable for the students to present). In addition, more research should be conducted towards identifying the perceptions regarding the effectiveness of online education held from online students, faculty and administrative personnel. As more data becomes available researchers can determine ways through which skills and interaction based courses like communication can be effectively taught in an online environment. With further research results, employers will be able to direct adult learners towards the delivery mode that is best suited to the individual learner’s needs.