|

Introduction

The authors developed, implemented, and facilitated

a program to train and support faculty in the

effective use of an online course management system,

WebCT/Blackboard, at Anna Maria College (AMC). This

article describes the rationale, planning process,

implementation, assessment, and future goals for

ongoing professional development to support online

teaching and learning at AMC.

Few

faculty members possess the pedagogical or technical

ability to effectively develop and deliver online

courses (Oblinger & Hawkins, 2006). In addition,

regional accreditation requirements recommend an

ongoing program of technical, design, and creation

support for faculty members using distance education

(New England Association of Schools and Colleges,

2001). Regional accreditation also requires that

students enrolled in online courses acquire levels

of knowledge, understanding, and competencies

equivalent to those achieved in similar programs

offered in more traditional time periods and

modalities. Considering the need and mandate for

professional development, AMC supported the

development of a faculty certification course to

enhance pedagogical and technical skills.

The

primary focus of AMC faculty is on the growth and

success of their students. Faculty professional

development centers on teaching and learning, with

the mission of faculty development at AMC to value

reflective practices that result in systematic

assessment, quality improvement, and openness to

growth. To support this mission, the facilitators

used an educational philosophy based on research in

the field of cognitive psychology and the philosophy

of John Dewey (1938). Both Vygotsky (1986/1934) and

Dewey believed that thought is a tool and that ideas

have flexibility. Vygotsky considered cognition to

be primarily a social experience. A zone of proximal

development occurs when the person transfers

abilities from a shared environment to knowledge

within the self. A philosophy in which learning is

internally created and socially mediated is called

constructivism. A constructivist educational

philosophy guides preparation and influences the

delivery of faculty professional development at AMC.

Because faculty development focuses on improving

teaching, the facilitators used elements of

constructivism in designing the WebCT faculty

certification course. Adams (2009) explains that

relationship building, collaboration, inquiry, and

reflection are central elements of constructivism.

These elements are seen in the course in several

discussion topics. For example, the Introductions

discussion topic builds relationships, and

reflection is encouraged throughout all the

discussion questions.

The

faculty certification course incorporates a

student-centered approach that should produce

significant learning. Fink (2003) defines

significant learning with a process and an outcome

dimension. The process of learning begins by

activating prior knowledge. During the process of

learning, participants are highly engaged. The

outcomes include significant and meaningful change.

Using a student-centered approach could present a

potential challenge because faculty develop

conceptions about teaching based on their

experiences as a student or novice teacher and may

have established an orientation to teaching that

could limit the way they provide instruction

(Holmes, 2004; Northcote, 2009).

Engagement happens with hands-on practice, which is

essential to significant and active learning.

Constructivist beliefs are the basis for active

learning (Stewart, Bachman, & Babb, 2009). The

Association for Supervision and Curriculum

Development (2010) states, “Active learning is based

on the premise that if students are not active, they

are neither fully engaged nor learning as much as

they could” (para. 11). Course facilitators should

consider that active learning may need to be taught,

and that participants may resist active learning

because they have prior expectations about learning

and teaching (Michael, 2007). In addition,

facilitators need to be explicit about course

pedagogy for the participants to understand the

principles of constructivism, significant learning,

and active learning.

The

facilitators use many techniques to produce

significant and active learning during course

implementation. These techniques include (a)

communicate high, but attainable, expectations

clearly; (b) explicitly relate current learning to

prior learning; (c) offer a variety of ways to

learn; (d) encourage hands-on practice; (e) present

information visually; (f) support reflection; (g)

provide prompt and concrete feedback; and (h) assign

tasks to include revisions (Chickering & Gamson,

1987; Suskie, 2009). Ideally, the WebCT faculty

certification course will recognize, develop,

implement, and evaluate innovative and effective

teaching and learning strategies that foster college

student engagement.

Method

Rationale

AMC

adopted WebCT as a course management system in

spring 2005. Within eighteen months, eleven faculty

(about 20%) were using the system without any formal

training. AMC’s Dean of Academic Affairs invited the

facilitators to develop a certification training

model for all faculty members who used the WebCT

course management system. The goals of the mandatory

training would be to assure consistency, quality,

and integrity in academic programs, and provide

full-time and adjunct faculty members with the

opportunity for enhanced and meaningful interaction

focused on teaching and learning.

The

AMC Electronic Learning and Teaching (ELT) committee

reviewed, approved, and recommended the faculty

certification course to the Dean of Academic

Affairs. The ELT committee decided the certification

course should be comprised of technological training

(30%) and pedagogy (70%). It should also include a

general WebCT orientation, discussion of

terminology, effective practices in e-learning and

teaching, mentoring, and coaching. Faculty

participants must successfully complete 80% of the

course to become WebCT certified.

The

original version of the course was delivered to the

first group of faculty in December 2006. The course

has since been taught eight times with the technical

support of the WebCT administrator. The course is

presented in a blended model and has been revised

each semester to better meet the needs of the

faculty and to model effective teaching practices.

The number of face-to-face sessions has varied based

on feedback, faculty need, and technological skill

level.

Participants

The

Dean of Academic Affairs invited full-time and

adjunct faculty members interested in using the

WebCT course management system to participate in the

training. To date, fifty-one faculty members

(thirty-six full-time and fifteen part-time)

successfully completed the course. Certified faculty

represent a variety of academic disciplines:

nursing, education, humanities, business, criminal

justice, science, visual art, music therapy,

sociology, psychology, fire science, and social

work.

Design

The

certification course was comprised of technological

training or process skills and pedagogy or content

knowledge. The facilitators purposefully designed

the course to guide the participants to

differentiate between these skills and knowledge to

effectively teach in the electronic learning

environment. In designing the course, the

facilitators considered faculty members’ personal

experiences with teaching and learning,

technological skills, and subject expertise. The

plan was to create a community learning environment

where faculty could work together as both students

and course designers. The facilitators developed

intellectually stimulating activities to promote a

deeper understanding of active teaching and

learning. Designed activities allowed participants

to explore technology, assessment strategies,

pedagogy, reflective teaching and learning, and

innovative practices.

In

designing the faculty certification course, the

facilitators used a variety of resources. They

relied on the Quality Matters (2006) standards and

website as well as information from the WebCT !mpact

2006 8th Annual User Conference (Henne, 2006; Smith,

2006). Because the facilitators are both from the

field of education, they used research from Bloom

(1956), Chickering and Gamson (1987),

Darling-Hammond and Bransford (2005), Fink, 2003;

Vygotsky (1986/1934), andWiggins and McTighe

(1998).;;

Course Objectives

The

facilitators designed the WebCT course so that

participants experienced it from both course

designer and student perspectives. The course and

syllabus were developed to support the following

objectives. Activities and experiences were designed

to facilitate participants’ ability to:

1.

Discuss effective teaching and learning.

2.

Utilize a variety of questioning strategies

(open-ended, clarifying, values, connective,

relational, synthesizing, and application).

3.

Discuss research-based practices to include the

importance of peer review.

4.

Practice course design in the WebCT environment.

5.

Develop a syllabus using a template and posting the

syllabus to WebCT.

The

first two objectives were the primary focus for the

faculty certification course. Participants

experienced the student perspective as members of

the course and as course designers; a “sandbox” was

available where they could experiment with the

development of a course that they would teach in the

future.

Implementation

Faculty members who participated in the course

shared their interests and expertise during

face-to-face meetings and through online

discussions. Facilitators encouraged participants to

discuss effective teaching and learning strategies

through the discussion topic. They guided

participants to use a variety of questioning

strategies. The first three topics, Introductions,

Netequitte, and Community Icebreakers,

were led by the facilitators, and methods for asking

open-ended questions were modeled. The questions

were posted in a discussion thread.

Next, participants were instructed in the technique for

facilitating a discussion thread. First, they read a

short article and reviewed a sample open-ended

question. Alone or with a partner they wrote a

lingering question in paragraph form. The

expectations for the open-ended question were that

it be original, relevant, and elicit a range of

responses. The questions began with a link to the

reading. After writing the paragraph, participants

shared their questions through the discussion board.

For

the remainder of the course, participants were

assigned responsibility for leading discussions on

predetermined topics that focused on the course

content readings; those who were not leading the

discussions were discussion participants.

After the first group of participants facilitated a

discussion, both groups reflected on and discussed

the following questions:

·

How did it feel to be a facilitator?

·

How did it feel to be a participant?

·

How might you provide feedback on discussions?

·

What criteria would you use?

·

How will you encourage students to be active and

involved?

·

How much will participation and discussion be worth

in your course?

Participants were asked to consider how they might

use discussions to promote learning within their

courses. The facilitators shared sample rubrics to

assess participation in discussion topics. The

remainder of the course developed technical skills

while reinforcing effective teaching and learning

strategies.

Measurements and Analysis

To

determine the effectiveness of the WebCT faculty

certification course, the facilitators measured and

analyzed course discussion threads, participants’

sandboxes, and the course evaluations. Ongoing

analysis throughout the course served to provide

formative assessment, and the course was revised

based on needs, interests, and preferences. In a

summative fashion, the analysis was used to improve

future revisions of the course. Data were analyzed

to generate categories, comparisons, and

relationships among responses. Through open coding,

data were closely examined and compared for

similarities and differences. The analysis

identified participant inquiry and reflection, which

are indicators of significant learning (Fink, 2003)

and central elements of constructivism (Adams,

2009).

Discussion Threads.

Throughout the course, participants engaged in

online conversations through discussion threads. The

threads were divided into different topics that

allowed participants to create discussions around

specific subjects. The facilitators provided

materials and resources including scholarly

articles, PowerPoint presentations, and URLs on each

topic. Directions for how to participate in each

discussion thread were provided and included guiding

questions to help participants focus on inquiry and

reflection.

Facilitator-Led Discussions. The facilitators led the first three discussion topics,

Introductions, Netiquette, and

Community Icebreakers. The goal was to model

methods for responding to participant postings by

rephrasing key points, providing additional

resources, and asking open-ended questions to

promote further discussion. Participants were

expected to respond to the initial posting, to two

other participants, and to anyone who responded to

them.

Introductions.

The

first discussion topic led by the facilitators was

Introductions. The purpose of this topic was

to encourage participants to learn about each other

beyond the classroom environment, to model

open-ended questioning techniques, and to

demonstrate responses that promote discussion.

Participants introduced themselves to their

colleagues and answered one of the following

questions:

-

If you were on a deserted island and could only bring

one book, which book would you bring? Why?

-

If you had to describe yourself as an animal, which

animal best matches your personality? Explain?

-

What are three websites you go to every day and why?

Analysis of the Introductions thread showed

participants sharing personal information,

identifying commonalities, asking clarifying

questions, and providing resources to their

colleagues. Facilitators responded to each

participant by commenting on a point of interest in

the posting, adding personal information, and asking

an open-ended question to encourage additional

discussion. The Introductions topic provided

an opportunity to build a sense of community and

presented a chance to preview participants’

netiquette skills.

Netiquette.

The

second discussion topic, Netiquette or rules

that guide electronic written communications,

required that participants review a PowerPoint

presentation. The facilitators provided the

following guiding questions:

·

How did you learn the “rules” of emailing?

·

Can we assume students know our rules?

·

How will you communicate your expectations about

netiquette to students?

·

Would you add any rules or considerations that we

may have missed in the PowerPoint presentation “What

Is a Quality Course?”

Analysis of the Netiquette topic demonstrated

that participants learned netiquette as they learned

new technology. Participants discussed that as

technology changes there are new expectations that

can create confusion. They reflected that new

technology requires a learning curve for teachers

and students, trial and error, observing others, and

assistance in learning the rules. Because of the

learning curve, instructors should assume nothing,

set clear expectations, hold students accountable,

and have a student policy and procedure guide.

The

majority of participants who responded to the final

guiding question felt that the PowerPoint

presentation adequately covered the rules and

considerations of netiquette. One participant

suggested an addition to the PowerPoint in regard to

the lack of ability to read body language with

online communications. This response became the

focus of a reflective discussion about the

importance of considering the fact that students who

communicate nonverbally may initially find the

online environment difficult to navigate. After

reading the discussion about nonverbal

communication, a participant responded, “I wonder if

students who have visual limitations could be able

to teach us something about this. How do these

students make up for the lack of visual cues when

they participate in face-to-face courses? Is there

something they can teach us that would make

electronic learning more effective?”

Community Icebreakers.

The third discussion topic, Community Icebreakers,

is the last of the initial facilitator-led

discussions. Participants were asked to read and

reflect on the Seven Principles for Good Practice

in Undergraduate Education (Chickering & Gamson,

1987). The guiding questions that provided focus for

the Community Icebreakers topic were:

•

How do icebreakers fit in?

•

How do you make learning collaborative and social?

•

How do you build community?

•

How will you have students participate in

activities that encourage them to get to know each

other?

Analysis of the Community Icebreakers thread

showed that participants shared a variety of

specific icebreaker activities they have employed in

their classrooms. Ideas included sharing a favorite

website, providing information about a favorite book

or hobby, or participating in an online survey on

learning styles and discussing similarities and

differences. In addition to sharing ideas about

icebreakers, they reflected on the assigned

readings.

Participant-Led Discussions.

After sharing in an activity designed to assist

participants with the development of open-ended

questions, participants were assigned responsibility

for facilitating discussions that focused on the

course content readings; those who were not leading

the discussions were discussion participants. The

facilitators posted an opening question, responded

to all participants, worked to keep the discussion

thread on topic, and provided a summary of the

thread to include a list of any resources. The

topics that were led by participants were

Objectives, Learner Interaction,

Resources and Materials, Assessment and

Measurement, and Effective Feedback.

Objectives.

Facilitators for the Objectives discussion

were asked to reflect on the Quality Matters (2006)

standards for learning objectives. Guiding questions

included:

·

How will you write measurable objectives?

·

How will you design your course to meet your

objectives?

·

How many of the competencies identified in the

article do you possess?

Analysis of the Objectives topic demonstrated

that participants reflected on objectives from a

variety of experiences. Participants who were new to

teaching requested pragmatic assistance with

generating objectives. Participants who taught in

programs that involved external accreditation helped

others to realize the requirements of predetermined

course objectives.

Some participants discussed the importance of

reviewing objectives throughout the semester. Others

reflected on objectives as they relate to the

program level, course level, and lesson level. One

participant stated, “the course objectives should

flow well from the program objectives. I will be

working to ensure that the individual unit

objectives also flow well from the course

objectives.”

Learner Interaction.

Facilitators for the Learner Interaction

discussion were asked to reflect on the Quality

Matters (2006) standards for learner interaction and

use the following guiding questions to frame their

discussion:

·

How will you use questioning techniques in your

course?

·

How will you use instructional strategies and WebCT

components to promote learner interaction?

·

How many of the competencies identified in the

article do you possess?

A

question generated by one of the facilitators for

the Learner Interaction thread presented an

example of reflection on the need for liveliness in

teaching.

Liveliness appears an essential ingredient in

bolstering and assuring levels of active

participation. It seems, then, apparent that the

media used for relaying course content can either

elicit or dampen curiosity! If we seek to cultivate

high levels of motivation and stimulate intellectual

and personal growth on the part of hopefully many

excited learners in the class, what practical steps

can be taken to foster this good “Learner

Interaction” and build genuine interest?

The

summary of the discussion on liveliness in teaching

provided a synthesis of the discussion and an

overview of the breadth and depth of the topic that

was covered in the discussion.

Our

discussion yielded a sense of the potential and

promise that new media offer to the academy as well

as a cautionary sensibility around possible

denigration of the teaching enterprise when and if

resources are poor or lack truth in reporting. . . .

I do think we can make the claim that a critical

evaluation of resources may preclude problems and

ensure a class is committed to veracity as well as

creativity in the new, media-rich contexts we

currently enjoy and which can surely enhance the

learning experience and our life ventures.

Resources and Materials.

Facilitators for the

Resources and Materials

discussion reflected on these guiding questions:

·

How do your instructional materials have depth in

content and comprehensiveness for the student to

learn the subject?

·

How do you accommodate different abilities of

students?

·

How do you present instructional materials in a

format appropriate to WebCT, which are easily

accessible to and usable by the student?

·

How do you make the purpose of the course elements

(content, instructional methods, technologies, and

course materials) evident to students?

Analysis of the Resources and Materials

thread illustrated participants’ willingness to

share the materials and resources they used and ways

they might change as they move to an online format.

“Some of the issues brought up included how to

utilize technology for group work and the challenge

of how to overcome the ’face-less,’ impersonal

aspect of online teaching.” Resources were provided

that discussed the issue of technology in the

classroom and the important consideration that both

students and faculty come to the classroom with

differing technology skills. Other discussions

“raised the question of information versus knowledge

and of material that might be classified as

entertainment and what educational purpose that

material might have.” Some postings posed questions

regarding the “use of ‘open sources’ such as

Wikipedia and the educational value of them if used

properly.”

Assessment and Measurement.

Facilitators for

Assessment and Measurement reflected on a PowerPoint

presentation that focused on Quality Matters (2006)

standards for assessment and measurement. Guiding

questions included:

-

How do you align the types of assessments selected

to the learning objectives and course activities and

resources?

-

How is your grading policy transparent and easy to

understand?

-

Are the assessments selected appropriate for WebCT?

-

Do you use both formative and summative assessment

strategies?

Analysis of the Assessment and Measurement

thread showed participants shared practical

strategies and tools for assessment and discussed

the pros and cons of a variety of methods.

Exploration of assessment in inquiry-based learning

promoted discussion of authentic assessment and the

use of rubrics “guided by what the real world

expects of a practitioner in the field.”

Participants reflected that “obtaining input from

students in the development of rubrics, or relying

on the requirements of an external body or

professional performance standards” may be helpful

when developing assessment criteria. Participants

grappled with “achieving equitable assessment when

students may be bringing different experiences and

perspectives to the project.”

Effective Feedback. Facilitators for the

Effective Feedback

discussion were asked to reflect on:

·

Which strategies provide effective feedback to the

student?

·

How do you use formative assessment strategies?

Analysis of the Effective Feedback topic

demonstrated that there was a general consensus

among participants regarding the definition of

effective feedback. They agreed that “effective

feedback should include positive and encouraging

language with importance on being polite and

respectful. In addition, the content must be

relevant and individualized.” A list of attributes

that can and should be observed were developed:

·

Timely

·

Clear

·

Thorough

·

Consistent

·

Equitable

·

Professional

Participants discussed different ways feedback could

be delivered by the instructor as well as

“mechanisms that best enable students to self-assess

their own performance.” A majority of participants

were able to gather the information they needed for

feedback from classical methods of outside

assignments and quizzes. “Should a student exhibit

difficulty in any area, the instructor would

schedule a conference and try to work with the

student on a more individualized basis.” Most of the

participants felt this model could be easily

adaptable to online learning.

The

final discussion topics, Best Practices and

Resources for Further Study, were led by the

facilitators. At this point in the course

participants had completed instruction on course

design and had worked in their sandbox. Each

discussion topic opened opportunities for reflection

and inquiry. As the course continued and colleagues

shared their thoughts, reflective topics such as the

discussion on nonverbal communication were added to

course content.

Sandbox.

Participants designed their initial course in a

sandbox or course shell. Designing in the sandbox

allowed for hands-on practice and permitted

facilitators to provide prompt and concrete feedback

on the three layers of course design. Participants

reflected on the feedback and used inquiry to make

the required changes.

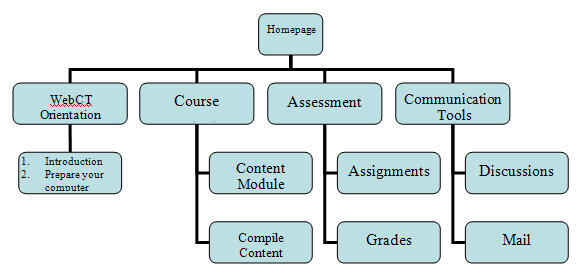

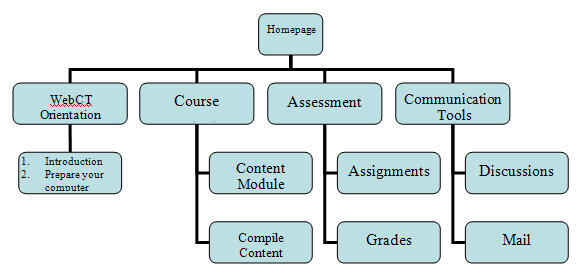

Layer One is the initial display or homepage of the

course in WebCT. It includes the color scheme, upper

and lower text blocks, preloaded links to Layer Two,

and a frame with a preloaded course menu. There are

nine items on the standardized course design

template in Layer One. See Figure 1 for a visual

representation of the layers.

Analysis of the common errors in Layer One included:

·

Changed the colors of the course template or

background color of the text blocks.

·

Added too much information or too little

information to the upper text block, which was

designed to provide the basic course information

(course number, course name, class meeting day,

times, place, and instructor’s name).

·

Added additional links to the four preloaded links.

·

Omitted the date in the lower text block, which is

intended to initially welcome students and provide

updates as the course progresses.

·

Did not change the preloaded message in the lower

text block.

·

Created a message that might not be perceived as

welcoming in the lower text block.

·

Deleted or added too many links to the course menu,

which included four preloaded links. Participants

could add up to two additional links; some added up

to six additional tools.

Figure 1. Visual Representation of

Course Design Layer

Layer Two of the AMC standardized course design

template has five sections: course content,

assessment, communication tools, the syllabus, and

resources. Analysis of the common errors in Layer

Two included:

·

Neglected to upload the course syllabus file to the

syllabus tool.

·

Overlooked using the AMC standardized template to

develop the course syllabus.

·

Unchanged preloaded items of additional materials

and Web links.

·

No pages or tools added to resources, which is

linked to the course menu.

Participants added their specific course materials

to sections in Layer Three. There were a total of

four items in Layer Three: adding information to

course content, assessment, communication tools, and

resources. Analysis of the common errors in Layer

Three included:

·

Failure to upload files to the headings in course

content.

·

Not adding details such as due dates, questions,

and points in assessment.

·

Failure to add instructions for students in

discussions.

·

Included http:// twice when adding a URL to

resources.

Layer Three presented the most difficulty based on

the analysis of the data. In Layer Three,

participants needed to upload files and create the

delivery model for their course. Layer Two required

the least amount of additions because the WebCT

administrator preloaded much of the layer into the

course shell. The facilitators provided specific and

concrete feedback on the sandbox. Many participants

required individual attention and technical

assistance to understand how to add materials to

their sandbox. Participants were encouraged to

experiment and “play” in the sandbox as a form of

inquiry.

Course Evaluations.

At the end of the certification course, participants were required to

provide feedback as part of their assessment

process. The course evaluations produced a 100%

response rate and clearly indicated possibilities

for improvement. Over time, the facilitators revised

the course evaluation form and, in spring 2007,

aligned the current form with the Quality Matters

(2006) standards. All faculty members completed

items on a Likert scale and responded to open-ended

questions. The results shown in Table 1 are from a

total of eighteen faculty members who completed the

course from spring 2008 to summer 2009. A Likert

scale assessed the quality and support systems of

the faculty certification course design using

Quality Matters standards.

A

series of open-ended questions were used to evaluate

course content. The responses were compiled and

transcribed into a summary document. The

facilitators read the transcribed data, line by

line, and divided the data into meaningful

analytical units. Next, the data were coded with

inductive category names developed by the

facilitators by directly examining the data. The

questions on the course evaluation were:

·

What did you enjoy most about this experience?

·

From the perspective of a WebCT student, describe

your significant learning.

·

From the perspective of a course designer, describe

your significant learning.

·

How might you change your teaching based on this

course?

·

How could we improve this course and facilitation?

·

How can we improve the infrastructure of electronic

teaching and learning at

Anna

Maria College?

Participants reflected that they enjoyed the

experience and gained technical skills, information

and resources, and pedagogical knowledge including

the demonstration of effective facilitation. They

appreciated the collegiality of the experience. Two

faculty members responded that they can empathize

with their college students more effectively after

participation in the course.

Significant learning was reported by the

participants. Understanding the importance of

socially mediated learning was an area of growth for

about half of the participants. The participants

also learned much about the role of the facilitator,

including the time commitment involved in teaching

online. They gained new technical skills and have

access to many new resources.

Participants will change their teaching practice

based on the certification experience. Changes

reported include the use of a variety of methods for

learning such as creating opportunities for student

interaction; improved organization and clear

communication of expectations; promoting

relationship building; aligning measurable

objectives, activities, and assessment; and

utilizing new assessment techniques.

The

facilitators received specific information on how to

improve the course. The content could be improved by

making expectations clearer, allowing more time for

the course, providing additional support, and

spending more time working on course design with

more instruction on assessment components. The

facilitation could be improved by allowing for more

socially mediated learning, providing more prompt

and concrete feedback, relating current learning to

prior learning more effectively, and offering more

hands-on practice of technological skills.

AMC

could improve the infrastructure of electronic

teaching and learning by hiring more personnel for

ongoing professional development and technological

support. This could include the creation of a

faculty certification instructor guide, the

development of a formal mentoring process (train the

trainer model), and a voluntary peer-review process.

There is a need for more physical space on campus

for larger computer labs. Technological upgrades

should be continually supported with funding and

personnel. One participant suggested that the

certification course could include a discussion on

educational philosophy. In addition, the college

should plan curricular changes to offer students

more technological training and guidance.

Discussion

Findings

Fink (2003) describes six aspects of significant

learning, one of which is learning how to learn.

Learning how to learn requires inquiry and

reflection or learning how to seek information and

construct knowledge. Fink defines inquiry as the

ability to ask and answer questions. In the faculty

certification training, evidence of inquiry included

formulating questions, sharing resources, and

effectively facilitating discussions. Reflection

allows people to make meaning of experiences and

information. Evidence of reflection included

acknowledging new technical skills, engaging in

dialogues to search for the meaning of course

experiences, and writing about their learning

process. Using these definitions of inquiry and

reflection, the facilitators analyzed course

discussion topics, participants’ sandboxes, and the

course evaluations. The analysis confirms that the

faculty certification course effectively promoted

inquiry and reflection for the participants.

Table 1. Likert Scale Items from WebCT Faculty

Certification Course Evaluations.

(SD = Strongly Disagree, D = Disagree, N = Neither agree or

disagree, A = Agree, SA = Strongly Agree, NR = No

Response)

|

Standard Quality |

SD |

D |

N |

A |

SA |

NR |

|

Learning Objectives (essential)

A statement of the specific and measurable

knowledge, skills, attributes, and habits that

students are expected to achieve and demonstrate

as a result of their educational experiences in

a program, course, or module was clear.

|

|

|

1 |

4 |

12 |

1 |

|

Assessment and Measurement

I received specific comments, guidance, and

information provided in response to an activity

or assessment. Feedback was integrated to the

established criteria, and the instructors

provided reasons for the accompanying evaluation

and the resulting grade. |

|

|

|

4 |

13 |

1 |

|

Resources and Materials

The course provided instructional materials that

support the stated learning objectives. The

materials had sufficient breadth, depth, and

currency to learn the subject. The instructional

materials were logically sequenced and

integrated. |

|

|

1 |

2 |

14 |

1 |

|

Learner Engagement

The learning activities promoted the achievement

of stated learning objectives.

Learning activities fostered instructor-student,

content-student, and if appropriate to this

course, student-student interaction. The

requirements for course interaction were clearly

articulated. |

|

|

1 |

2 |

14 |

1 |

|

Course Technology

The tools and media supported the learning

objectives and were appropriately chosen to

deliver the content of the course. The tools and

media enhanced student interactivity and guided

the student to become a more active learner.

Technologies required for this course were

either provided or easily downloadable.

Instructions on how to access resources at a

distance were sufficient and easy to understand.

|

|

|

|

6 |

11 |

1 |

|

Support Systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The course instructions articulated or linked to

a clear description of the technical support

offered. |

|

1 |

1 |

4 |

9 |

2 |

|

The course instructions articulated or linked to

an explanation of how the institution’s academic

support system can assist the student in

effectively using the resources provided.

|

|

2 |

|

4 |

8 |

3 |

|

The course instructions articulated or linked to

tutorials and resources that answer basic

questions related to research, writing,

technology, etc. |

|

1 |

|

6 |

8 |

2 |

Limitations of the study

This study was limited in several ways. The results

are applicable only to the facilitators’ work

setting, and the sample size was relatively small (N

= 51). The facilitators collected data randomly;

therefore, a more systematic approach to data

collection would strengthen the findings.

Conclusions and Future Research

The

facilitators have observed that successful course

completers use the pedagogical knowledge from the

course in both blended and face-to-face courses. For

further study, the facilitators plan to research

whether faculty members experience shifts in

pedagogical beliefs after developing and teaching an

online course.

Based on course evaluations, the addition of

mentoring and peer review are needed at AMC. If

these processes are implemented, the facilitators

will study the effectiveness of faculty support

after the initial training. Are there differences

between early adopters and the faculty who were

required to participate in the certification

course?

This article described the rationale, planning

process, implementation, assessment, and future

goals for ongoing professional development to

support online teaching and learning at AMC. The

WebCT faculty certification course effectively

supports inquiry and reflection in faculty and,

according to one participant, supports the

recognition and respect of one’s own diversity and

that of others: “We are from varied fields, social

work, psychology, English, business, economics,

religion, history, writing, fire science . . . and

our collaboration has been awesome . . . who would

have thought that? Maybe this is a lesson for us

about online students . . . who come with different

agendas, cultures, ethnicities, socioeconomic status

. . . and yet we find common ground.” |