Introduction

All too often, students, in a range of college programs, typically view basic research literacy courses as boring, anxiety-provoking and irrelevant to their program of study (Papanastasiou, 2005). These negative attitudes create barriers to learning and are associated with poor course results (Adams & Holcomb, 1986). This situation presents a serious problem as employers have identified the very skills developed in research courses such as finding and evaluating information, making decisions and thinking critically as essential for work, continuous learning and a successful life (Human Resources Development Canada, 2009).

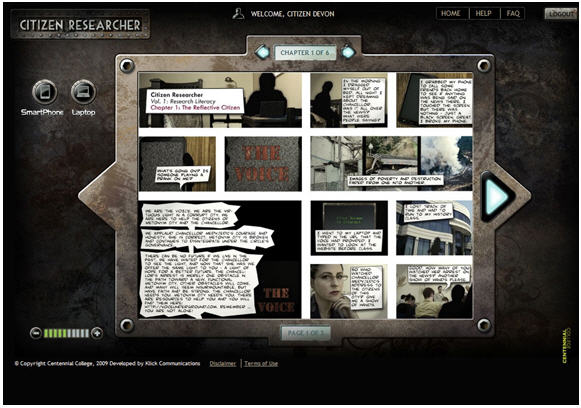

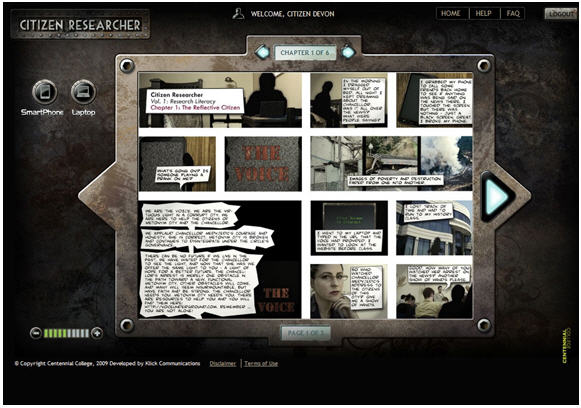

To address the vital need for research literacy in today’s graduates, a multimedia/curriculum team developed an online graphic novel called Citizen Researcher (CR). The graphic novel was developed to stimulate interest and motivation regarding research literacy concepts. The novel includes nine chapters that present research literacy skills in the context of the unfolding story. The learner adopts the role of a citizen living in a vast metropolis in the near future who learns the value of becoming ‘research savvy’ and the skills that are needed to achieve that goal. As learners journey through the story they are presented with resources via a virtual mobile phone, and engage in learning activities through a virtual laptop. Both these mechanisms are integrated into the story and the learning environment itself; the learner does not need to leave the story to access these resources or to apply new learning (Figure 1). A pilot research study was conducted with community college students to determine the efficacy of the graphic novel and explore learners’ experiences.

Figure 1. Screen shot from Citizen Researcher showing the graphic novel interface and the links

to the smartphone and laptop resources

Each of the nine chapters has a theme which is tied to a major educational objective:

- Chapter one, The Reflective Citizen : The learner explores the reflective cycle, reflective journaling and the importance of critical thinking in evidence-informed decision making.

- Chapter two, The Inquiring Citizen : The learner delves into the task of forming a well constructed problem statement and practices brainstorming to develop robust research questions.

- Chapter three, The Seeking Citizen : The learner is introduced to the different ways knowledge is acquired. Learners explore the difference between information sources, how to use e-resources and to examine information for bias.

- Chapters four through seven, The Thoughtful Citizen, The Methodical Citizen, The Perceptive Citizen and the Analytical Citizen : Learners are introduced to research studies and the specifics of qualitative and quantitative research. These chapters include activities related to sampling, validity and reliability, data analysis including descriptive and inferential statistics, and research designs.

- Chapter eight, The Innovative Citizen : Learners explore knowledge transfer and dissemination while promoting principles of academic honesty. In-text citations and referencing are reviewed.

- Chapter nine, Citizens United: This chapter advances the idea of knowledge transfer by encouraging networking for the further dissemination of information.

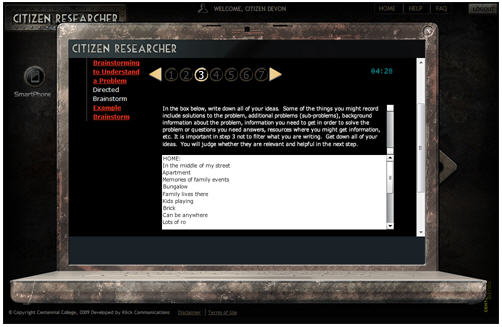

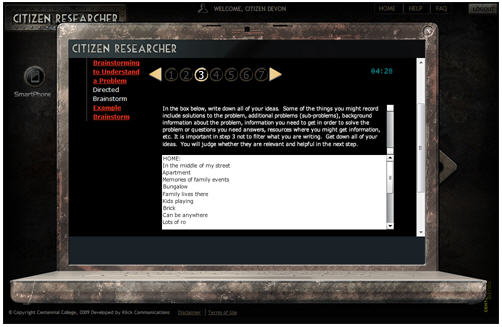

Citizen Researcher is presented in a custom-built, web-based platform that allows the learner to read the story as full pages or from panel-to-panel linearly depending on individual preference. The learning resources and activities are presented through the virtual laptop or phone as frames to a separate repository. An administrative system allows for the creation of any number of pages, chapters, and novels, which consist of jpeg images, mp3 sound files, and some text files to configure titles and URLs (Figure.2).

Figure. 2 Screenshot demonstration of a learning activity presented through the virtual

laptop. This one is a directed brainstorm exercise .

Literature Review

In the past 20 years, the graphic novel has emerged as a potentially useful medium to support cognitive, literacy and social outcomes (Carter, 2007; Downey, 2009; Waite & Davis, 2006). Increasingly, educators view the graphic novel as much more than what Yang (2008) called a “thick comic book”. They are starting to recognize the potential that the graphic novel holds in engaging students who are visual learners (Hassett and Schieble, 2007) and those who have had a steady diet of visual images through the Internet, television and video. Indeed, as more and more visual imagery and video make their way onto the Internet, visual literacy as well as verbal literacy will become important learning outcomes in our education programs (Callaghan, 2009).

The graphic novel has been identified by some researchers as a way to develop these multimodal literacy skills and to help students make meaning of text and media ( Hammond, 2009). Some authors believe that the graphic novel helps to portray complex concepts that are difficult to grasp when conveyed simply by text and that it demands more complex cognitive skills of the reader (Thompson, 2007).The graphic novel could also be a way of encouraging students to read: an important outcome when reading for pleasure is in decline with the middle school aged population (Edwards, 2008). Edwards reported that middle school children who participated in a study on graphic novels improved their reading comprehension, vocabulary and intrinsic reading motivation scores.

Short and Reeves (2009) argued that the graphic novel has potential in education because it appeals to the visual reader, a characteristic of many of our current students who are familiar with, and enjoy this format. These authors suggested that the graphic novel qualifies as an example of a “cool medium” as described by Marshall McLuhan. McLuhan (1964) described cool media as those that require the audience to use their imagination to complete the experience. Short and Reeves suggested that graphic novels are engaging because they provide some visual detail but leave much to the reader’s imagination. They also suggested that more research is needed to examine student satisfaction and experience with the graphic novel. While the emerging literature supports the integration of the graphic novel in curricula, there is a paucity of research studies that describe the use of the graphic novel as a teaching tool (Callaghan, 2009) and in particular, college students’ experiences and the impact on their learning. The purpose of this pilot study was to gain an in-depth understanding of what it is like to learn using a graphic novel and to explore students’ perceptions of their learning using CR.

Ethics

The study was approved by the participating college’s research ethics board. Participants provided informed consent for the study.

Research questions

The research project questions included:

- What impact does Citizen Researcher have on students’ perceptions of their research literacy skills?

- What is the students’ level of satisfaction with the course content, design delivery method and learning activities?

- What are students’ experiences with Citizen Researcher?

- What are the strengths, challenges and barriers associated with this new model of course delivery?

Methods

The intent of the pilot study was to test the functionality, usability and pedagogical value of CR. A descriptive study, using surveys and interviews was conducted to gain an in-depth understanding of what it is like to learn using a graphic novel as this is a very recent innovation in online learning.

Sample

A broadcast message was sent to the student population inviting students to participate in the study. Twenty-four students responded and the final sample included 18 full time undergraduate students in 14 programs who were attending post-secondary college in a large city.

Demographic survey

Three surveys were administered: a demographic survey, a Research Literacy Competency self-report survey and a Course Satisfaction survey. The demographic survey, administered online at the start of the course, was developed by the research team to provide a profile of the learners that included age, sex, educational level, reading habits and Internet skills.

Research Literacy Competency Survey

A pre-post Research Literacy Competency survey was used to measure learners’ self-reported research literacy skills before and after the course. The survey was adapted from a survey developed by Ryan, Campbell and Brigham (1999) and was designed to measure perceived change in competency after a continuing education course. The survey was designed to be adapted for specific courses. Ryan and her colleagues conducted several tests to enhance validity and test the reliability of the survey, including an expert panel review, Cronbach alpha, test-retest and factor analysis studies. The tool was modified by the evaluation team to match the Citizen Researcher learning outcomes. Members of the curriculum development team and advisory committee reviewed the survey to enhance validity of the survey items. The Cronbach alpha for the current study was 0.92, providing evidence for the reliability of survey items.

The survey consists of 8 items that measure the CR learning outcomes and was administered online. Students were asked to assess their competency in finding peer-reviewed articles, distinguishing between qualitative and quantitative research, differentiating between popular and scholarly literature, interpreting surveys, assessing bias and other outcomes. Participants use a Likert scale to measure their perceptions ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 = beginner and 5 = master level competency.

Course Satisfaction

Students completed an online Course Satisfaction survey, also developed by Ryan (1999) after they had completed the graphic novel and the integrated learning activities. The survey was modified for the current project and items were validated by the curriculum and multimedia development team and advisory committee members. The survey consists of 16 items that measure clarity of course objectives, relevance of learning activities, the experience of shifting between the CR storyline and the learning activities, the design of the graphic novel and whether the course improved students’ ability to understand research. Participants use a five-point Likert point scale to respond. The Cronbach alpha for the current study was 0.82, providing evidence for the reliability of survey items.

The survey also includes three open-ended items where students are asked to identify the novel’s strengths and recommendations for change. They are also asked to provide, if possible, an example of something new or different that they are doing or any changes in their thinking after completing Citizen Researcher.

Interviews

Because of the experimental nature of using a graphic novel to teach research literacy concepts, interviews were held to gain an in-depth understanding of students’ experiences. Seven (38%) students participated in individual telephone interviews that lasted 10 to 20 minutes. Researchers used a structured interview guide and the interviews were taped and transcribed. Students were asked to tell the researchers if they had completed the novel and why or why not. They were asked what was it like to learn using a graphic novel, what they had learned, what parts of the course had been most helpful, what was not helpful and their recommendations for change.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics using SPSS were calculated for items on the demographic, the Program Competency and the Course Satisfaction Survey. Inferential statistics were used to examine change in perception of program competency on the posttest once students completed the program. A content analysis approach was used to analyze responses to the open-ended questions on the post-course competency survey and to identify key themes from the interviews.

Results: Student Demographic Survey

Eighteen students completed the Demographic Survey. Ten (56%) were women and 8 (44%) were men. Their ages ranged from 17 to 49; the median age was 20 years. The majority, 89% (n = 16) were in their first year at college. Students came from a wide range of programs including lab technician, broadcasting, business administration, practical nursing and general arts and science.

The median number of books read per year, per student was 12, the mode was 3; the range was very wide, 1 to 70 books per year. Eight (44%) of the participants read five books or fewer per year; however, 10 (56%) read more than 12 per year and almost a quarter had read more than 25 books in the past year. There was no significant difference in the number of books read by female and male students. The most popular reading choice was comics, followed by novels, newspapers, non-fiction and blogs.

Internet skills varied widely among students. Eleven percent (n = 2) identified themselves as beginners, 61% (n =11) as intermediate and 28% (n = 5) as expert. Four students (22%) had previously taken an online course. None of the students had previously taken a formal research course.

Results: Research Literacy Competency Survey

The Research Literacy Competency survey was administered before and after students worked through the CR novel and learning activities. The average total score on the pre-course Research Literacy Competency survey was 27.8 (SD 6.5) out of a possible 40 (69.5/100). The minimum score was 13 (33/100) and the maximum was 40/40 (Table 1). The average total score on the post-course Research Literacy survey was 32 (SD 5.2) out of a possible 40 (80/100). The minimum score was 21 and the maximum was 40/40. There was a statistically significant difference in the mean pre and post research literacy scores for the total surveys (t = -3.29 ; df =17; p = .004).

All items on the pre-course survey received a mean score of 3 or higher on the five point scale. This result suggests that students who volunteered to participate in the study rated themselves as having fairly high research literacy competency levels even before reading CR. That said, gains were reported in every item on the post-course survey.

Table 1. Research literacy competency survey: pre-post mean scores and standard deviation (maximum score is 5) (n = 18)

Research literacy competency item |

Pre-course

mean (SD) |

Post-course mean (SD) |

I can use the internet to find peer-reviewed articles and information in my field of interest/ study. |

3.7 (.75) |

4.1 (.58) |

I can tell the difference between mass media and scholarly information. |

3.7 (1.1) |

3.9 (1.0) |

I understand the difference between qualitative and quantitative research. |

3.5 (1.0) |

3.9 (1.0) |

I know what bias is and how it alters the reliability of information. |

3.8 (.92) |

4.3 (.90) |

I understand how to interpret different types of quantitative data such as surveys. |

3.4 (1.0) |

3.9 (.87) |

I can identify strengths and weaknesses in the information I read. |

3.4 (1.0) |

4.0 (.76) |

I can use the College’s online resource centre to find a research article. |

3.1 (1.1) |

3.7(.80) |

I know how to formally analyze a research article. |

3.0 (1.0) |

3.6 (.84) |

Course Satisfaction Survey

The Course Satisfaction survey was administered after students completed CR. The mean total score for the survey was 65.5 (SD 5.6) or 82/100 and scores ranged from 56 to 76 or 70/100 to 95/100. The item with the highest score was, “I liked the graphic novel design”. Students felt that the storyline was clear and easy to follow. Regarding site design and functionality, most students reported that CR was easy to use, the information presented was easy to read and navigation was simple (Table 2).

All but one student ranked all items positively. This student disagreed with the items: “The objectives of CR were clear”, “The learning activities were interesting” and, “The learning activities helped me practice what I’d learned”. This student elaborated on his experience in the telephone interview. Three students (17%) reported they were neutral regarding the item, “I liked learning online”. All students agreed/strongly agreed that they would recommend CR to other students.

The three items with the lowest mean scores were, “It was easy to shift between the story and the learning activities”, “The learning activities were interesting”, and, “The learning activities enabled me to practice what I learned” These results are explained by results from the interviews. The mean for the item, “Citizen Researcher improved my ability to understand research” was 3.9/5. There was no statistically significant relationship between age and course satisfaction or the number of books read per year and course satisfaction.

Table 2. Mean Scores (SD) Course satisfaction survey items (range 1 - 5)

Course satisfaction item |

Item mean (SD) |

It was easy to find my way around Citizen Researcher |

4.1 (.61) |

It was easy to read the information provided |

4.2 (.57) |

The overall appearance of Citizen Researcher made it easy to use |

4.2 (.75) |

I liked the graphic novel design |

4.5 (.61) |

The story was clear and easy to follow |

4.4 (.70) |

Directions for learning activities were clear |

4.1 (.58) |

It was easy to shift between the story and the learning activities |

3.7 (.57) |

Citizen Researcher was well organized |

4.2 (.54) |

Citizen Researcher provided useful information |

4.0 (.84) |

Citizen Researcher improved my ability to understand research |

3.9 (.72) |

I gained skills that will be useful to me in the future |

3.8 (.70) |

The objectives of Citizen Researcher were clear |

4.0 (.84) |

The learning activities were interesting |

3.8 (.90) |

The learning activities enabled me to practice what I learned |

3.8 (.70) |

I liked learning online |

4.0 (.59) |

I would recommend Citizen Researcher to other students |

4.2 (.46) |

The Course Satisfaction survey also included three open-ended items where students were asked to describe what aspect of CR had been most helpful, unhelpful and to make recommendations for change.

Most helpful components

The most helpful part of CR, reported by 5 out of 17 (29%) students, was that the graphic novel design acted as an incentive to learn. Four students commented that the learning activities had been most helpful.

Least helpful/problematic components

When asked which parts of CR were not helpful or were problematic, five students said ‘none’. Some students reported that they were already familiar with the course concepts, two reported some confusion with the story, one reported not liking reading online and one said that the learning activities had not been helpful.

Recommendations for change

Two students felt no changes were needed. One student wanted the interface to be more user-friendly; he wanted to be able to enlarge individual screens. This response indicates that the student overlooked a function that is built into the system. Two students wanted the novel to be available for black and white printing. Two suggested that the flow between the learning activities and the story needed to be improved.

Key Learning

Students were asked to identify something important that they had learned from the course. Five students reported that they would begin to critically question what they were reading. Three commented that they had learned that the graphic novel has an important role to play in learning and two reported “research skills”.

Results: Interviews

Most students estimated that it took them about 20 minutes on average to read one chapter and complete the integrated learning activities.

The experience of using the graphic novel

All students, with the exception of one, were very enthusiastic about Citizen Researcher. They found the graphic novel approach to learning enjoyable and some said that it acted as an incentive to learn. One student noted, “It was great, I loved it. I thought it was really creative. I thought the way they did it was phenomenal.” They reported that it made a pleasant change from the usual lecture format and it stimulated their interest in reading and learning. They found the story realistic; several mentioned getting caught up in the story, wanting to know what happened next, and this experience acted as a driver to motivate them to keep reading. One student reported that her learning had happened effortlessly. She noted, “Ifound that I was learning but it was kind of an unconscious sort of thing, I wasn't, ‘okay, I've gotta read this now’. I just kept going back and it felt natural, interesting, because it's kind of little bit untraditional.” Two students described an interesting process; the story helped them to put the learning activities into context. “[It] brings what you learn into perspective.”

Part of the students’ interest in the story was because the main character was not defined in CR and some clearly put themselves into this role. One noted, “You can sort of use your imagination and put yourself in there, being part of the story.”

One student out of the seven interviewed had negative comments to share. This student was 49 and his primary objection was spending time developing generic skills, not the graphic novel format. He felt that time not spent building program-specific skills was time wasted. He recognized the importance of teaching basic literacy skills at college but did not think the novel’s theme was appropriate. He noted, “…this kind of a theme, it really overwhelmed the basic skill of being able to find factual information….You could’ve used a graphic novel with something less bleak, less grim than a society being turned into a totalitarian society”. He felt that the graphic novel was not suitable for the discussion of complex themes however, his satisfaction survey result was 76/100 and he felt the graphic novel was a suitable medium for high school students.

Impact on learning

Most students reported that CR had fostered their learning. Some students with prior research experience noted that CR reinforced their learning and helped to clarify previously confusing content. Students with no or little previous experience said that it helped to develop their basic research skills. One student noted that CR would be helpful in assisting students to make the transition from high school to college. She discussed the challenge of doing her first college research paper when she had never used an online database to obtain research resources and had never been required to formally reference a paper to the extent required by the College. These students particularly appreciated learning these skills in the world of Citizen Researcher.

Impact on thinking/behaviour

Students were asked to describe the impact that the novel had on their thinking or their behavior. Several students noted that it had further developed their critical thinking skills. One student said that CR would spur her on to investigate the information she retrieved on the Internet more thoroughly. One student noted, “It taught me a lot about looking past where the information is coming from, looking at how reliable things are. It made me question more about the information being presented, kind of look past what we’re being told”.

Story to learning activity transition

Most students found the process of moving from the story to the learning activities simple and easy.One student found the activities so integrated with the novel that she was not sure she had done them. She remarked, “I just found that I was so into it that I didn't even realize I was doing them”. One student however, found the transition choppy. He noted, “I know when you read the activities and when you read the novel you get experience of what it talks about in the story-like way but then it kind of made me forget what part did I finish. I’d have to go back to check what part I had to read next”. Two students missed the learning activities completely. One found them after reading a few chapters and then went back and completed them.

Technical issues

Most students did not have any technical problems with CR. Most commented that they could read the story online without difficulty. Two students had some difficulty grasping the navigation process and recognizing that clicking on a screen enlarged a frame. One student suggested a typographic change; the text balloons should be wider than they are high and that CR should employ a font that isn't all capitals because text is read more easily, particularly online, when the it includes upper and lower case letters.

Recommendations

One student suggested adding content and activities related to critiquing Internet information sources such as Wikipedia and making better use of the Internet as a research tool. She felt that many students accept the validity of Wikipedia’s information without question. She added that many students are not sure how to use the College online databases so they simply use Google to locate research. Another student suggested adding reputable reference citation tools to CR.

One student recommended keeping the learning activities reasonably short so that the learner does not become disengaged from the story. Another student indicated that CR include a brief introductory tutorial to help students orient to the novel as a learning object and to learn about navigation. Two students recommended that more emphasis be placed on the learning activities at the end of each chapter so they are not missed. One student asked that CR be downloadable to an e-reader.

Discussion

While a relatively new media, the graphic novel will be used increasingly as an educational tool in the hope that it will encourage reading in a generation of students who have become accustomed to a high degree of visual stimulation through video and television. This pilot study explored students’ experiences and learning outcomes with an online graphic novel designed to develop basic research literacy skills. The study was conducted to provide educators with an understanding of how students learn with a graphic novel and if that learning is effective. The use of both surveys and interviews provided a comprehensive picture of the phenomenon of interest. By combining methods, we were able to add depth to our understanding of the graphic novel as a medium for education.

The mean score of 82/100 on the Course Satisfaction survey suggests that most students had a fairly satisfactory experience; a result reported in other studies ( Hammond, 2009). Students reported that learning research literacy skills through this medium was enjoyable and the novel format acted as an incentive to read and learn. This finding, that graphic novels encourage reading, was reported in earlier studies (Thompson, 2007; Edwards, 2009). This innovative approach might be particularly useful when course content is particularly dry or difficult. Further, any approach that encourages reading is worth investigating. A large study, Adult Literacy in America (NCES, 2002) showed that 21% to 23% of Americans could not locate information in text and that they had difficulty inferring from text and integrating basic information.

The major objective and theme of the CR graphic novel is that critical thinking is essential to personal and societal survival. The most frequently reported outcome by students was that they had learned the importance of critical thinking; a result that demonstrates that CR was successful in delivering a major objective. The intertwining of story and learning activity, where the story illustrates the value of the learning activities, reinforced key concepts. Some researchers suggest that educators need to create environments where skills are demanded and practiced; that this will have more impact on skill development than any particular teaching method (Bereiter & Scardamalia; 2003). It is possible that the CR environment, as much as any of the learning activities, influenced students. This finding suggests that the graphic novel has significant potential in education. It may also be useful to those students for whom English is a second language. The use of graphics to accompany text may be particularly helpful to this group of learners (Carter, 2007).

The average total score on the pre-course Research Literacy Competency survey was 69.5/100 and the average total score on the post-course Research Literacy survey was 80/100. The statistically significant increase in scores on the Research Literacy competency pretest- posttest in spite of the high pre-course scores provides evidence that a relatively short online graphic novel was effective in helping students make gains in research literacy skills. Students indicated that they had gained skills in searching the online research databases and citing reference articles. These results reflect those parts of the course where students engaged in particularly interactive learning activities.

The mean score for the item, “Citizen Researcher improved my ability to understand research” was 3.9/5, a satisfactory result however, one which could be improved. Data from the interviews clarifies the survey results and suggests that some students did not realize the learning activities were part of the graphic novel activity and were therefore not completed. This result has implications for the placement of the learning activities within the novel and suggests that a brief introductory tutorial is needed. The team also plans to revise certain learning activities to ensure they provide a better ‘fit’ with each chapter to strengthen learning outcomes. Learning activities related to searching online databases, critiquing Internet resources and referencing sources were identified as particularly useful to students making the transition from high school to college. It is also important to remember this was a pilot study, Citizen Researcher was a stand-alone activity, it was not integrated with a full course; no grade was assigned. The learning activities are expected to have more impact when the novel is integrated into course curriculum. The learning objects however, will be contained in a repository that can be accessed independently of the story via computer or mobile phone and used in other research courses offered at the college.

One interesting finding was that three students (17%) reported that they were ‘neutral’ about learning online; two of these three respondents were new to online learning. While results from this study indicate that students were very positive about the graphic novel, educators will have to move forward in a thoughtful manner when introducing the graphic novel into the curriculum. We cannot assume that all our students have a strong technology background. This means that as always, educators need to choose the medium that best suits the program learning outcomes rather than simply adopting the graphic novel. Innovative learning environments such as the graphic novel can be useful in engaging learners however, they need to be part of a portfolio of other tested teaching strategies (Bates, 2009). This also means that some students will require assistance in making the transition to the graphic novel; we cannot assume every student has the skills to start without assistance.

This study met its goals and also served to generate questions for future research. How is the graphic novel perceived and interpreted by students whose second language is English? What impact does it have on their perceptions of college level reading? What impact would an online discussion board have as another component of the learning experience? What is the best fit regarding story theme and topic and college level course concepts? How closely does the story line need to match the concepts that are being taught? What is the best story length to learning activity ratio? Further, developing a graphic is a very labour-intensive and therefore costly process. The costs and benefits of this approach need to be documented and considered in educational program planning.

Limitations

This was a pilot study and included a small, self-selected sample. While their age and other demographic variables resemble the larger college student population, the self-reported pre-course Research Literacy scores indicated that students who volunteered for the study had a fairly high degree of basic research literacy and therefore may not be representative of the larger population of college students. They were also, as a group, strong readers; ten (56%) had read more than 12 books for pleasure in the past year and comics were a popular reading choice for this group. That said, a recent report, Reading on the Rise (NEA , 2009) indicates that the 18-24 age group had the greatest increase in literary reading, reversing a decline reported in 2002. The authors speculate this might be the result of a tremendous resource push to support reading in recent years. It is possible that other students would have struggled more with the graphic novel format or conversely, as more reluctant readers, they might have benefited more and reported a higher degree of satisfaction and learning. A further limitation is that self report measures were used to measure research literacy gains. Research using objective measures of research literacy gains is needed.

Conclusion

The results of this study support the ongoing development and integration of the graphic novel in college curriculum. The graphic novel provided an incentive for learning and helped students develop basic research literacy skills. The graphic novel holds promise in education, however, it should be used selectively and further work is needed to identify how it can be used most effectively with different curricula and student groups.

Acknowledgements: The team wishes to thank the Centennial College Applied Research and Innovation Centre for funding this research study and the Colleges Ontario Network for Industry and Innovation for funding the development of the graphic novel. The Applied Research Modules Working Group at Centennial College provided input on the curriculum and story content. Our thanks also include the students who participated in the study.