Introduction

Teaching has experienced rapid change in the last 20 years with the advances in the study of learning (Dervan, et al. 2006) . The Internet’s role in changing the form of teaching is transformative (Franzoni & Assar, 2007, Greenhow, et al., 2009 ). Some disciplines were early adopters of online mediated teaching but hospitality, recreation, and tourism (HRT) was not one of them. HRT instruction has historically used a hands-on learning approach with a concentration on social interaction. This study looks specifically at the learning perceptions and the use of leisure time of students enrolled in a traditional HRT program of study at an urban four-year university in Northern California. Since online social networking (OSN) happens as a recreation/leisure activity, exploring how students in a HRT program perceive online social networking and the role it plays in their lives is a new paradigm of study.

The differences in perceived learning between learning in an online or face-to-face (F2F) environment have been discussed for several years ( Batts, D. 2008, Atan, et al., 2004) . Fortune, Shifflett, & Sibley (2006) found that students enrolled in several online and F2F sections of a business communication course were similar with respect to their perceptions of skill development and learning, while differences were observed in the area of F2F interaction; the online students felt a lesser need for a F2F classroom setting and were satisfied with what they were learning regardless of the teaching modality. Supporting this finding, Larson and Sung (2009) determined that there are no differences in learning perceptions between the online and F2F delivery modes and that blended classes, e.g., ones that combine online and F2F instruction, do well when measuring learning effectiveness and student and faculty satisfaction.

Comparing the F2F and online learning modalities in the HRT curriculum is needed to determine whether students can develop and grow as hospitality, recreation, and tourism professionals with the desirable skills in leadership, interpersonal relationships, and customer service in a cutting-edge, high tech teaching environment with little or no physical contact.

Purpose

The first purpose of this study was to measure students’ learning perceptions related to a hospitality, recreation, and tourism program of study that uses two distinct teaching modalities—online and F2F classroom platforms. The other purpose was to explore the use of leisure time and online social networking. The approach for this study was to replicate prior research procedures and use the survey instrument developed by Fortune, Shifflett, and Sibley (2006) that measured learning perceptions of students enrolled in business communication courses in the two different learning environments—online and F2F.

University students enrolled in several sections of Introduction to Hospitality and Recreation (Recreation 1000) were asked to volunteer to participate in this study. The goal was to determine if there was a statistically significant difference in 1) student learning perceptions in relationship to the pedagogy/course environment (online vs. F2F), and 2) use of leisure related to online social networks.

Hypotheses

Researchers believed that there would be 1) no difference in perceptions of learning when comparing the online and face-to-face course delivery methods, and 2) online social networking (OSN) is a leisure activity and students would rather communicate electronically (online) as opposed to face-to-face (F2F).

Methodology

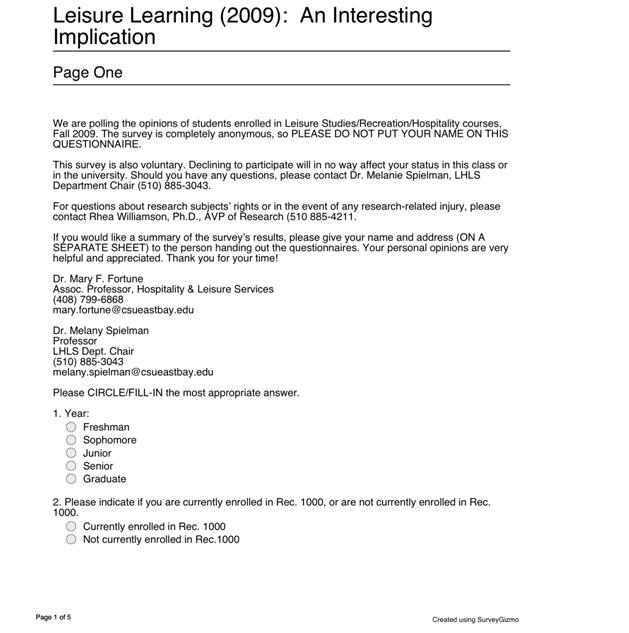

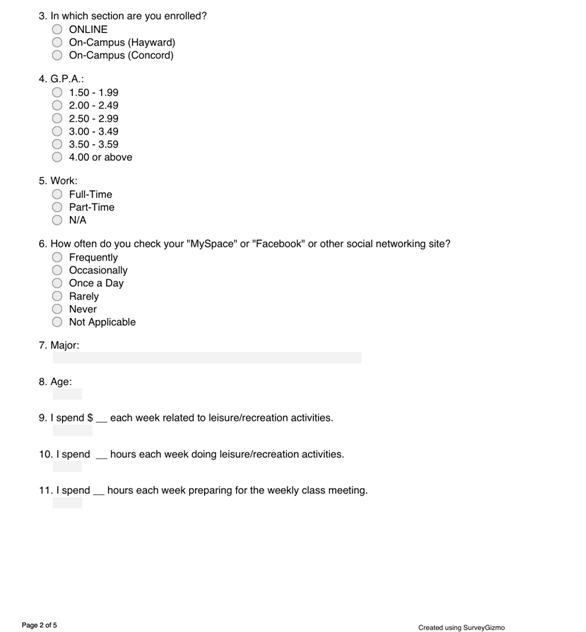

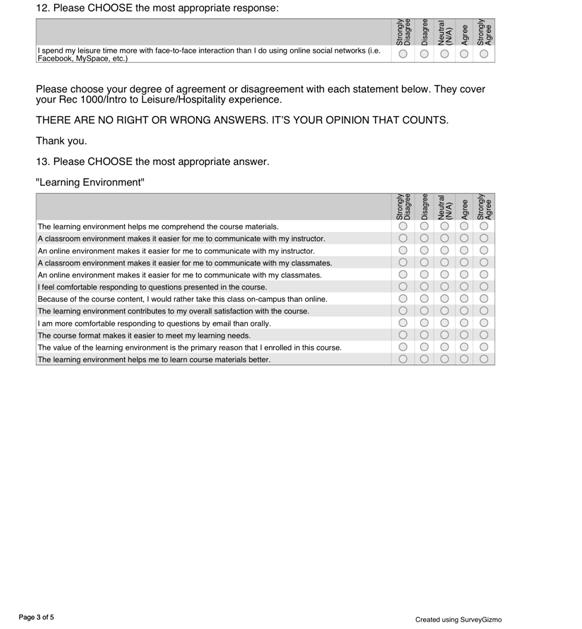

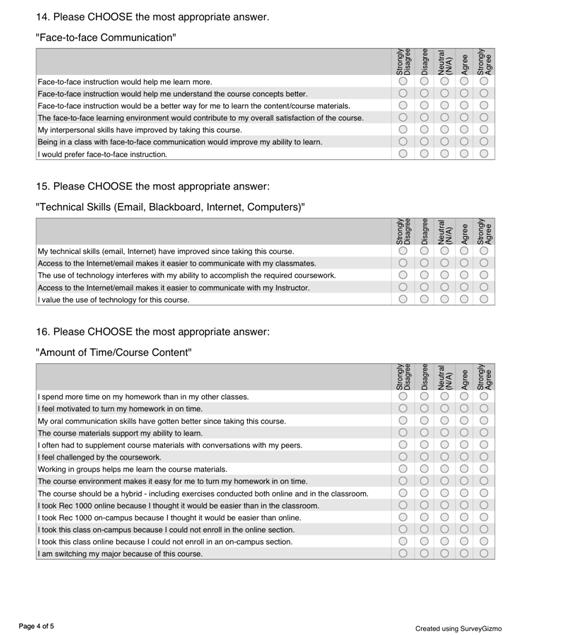

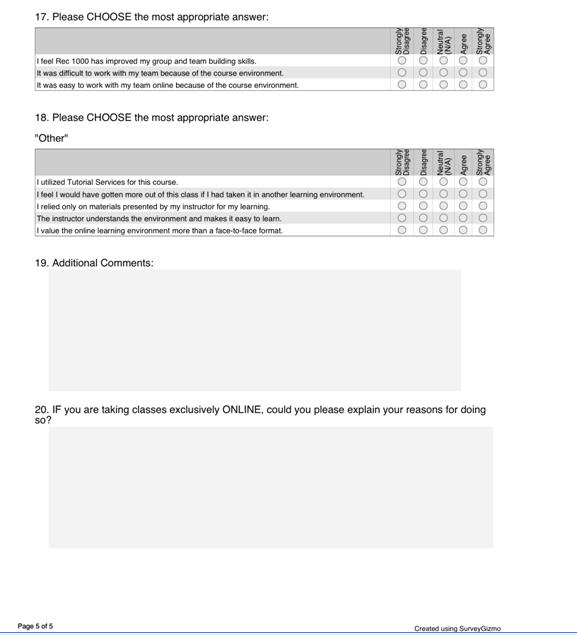

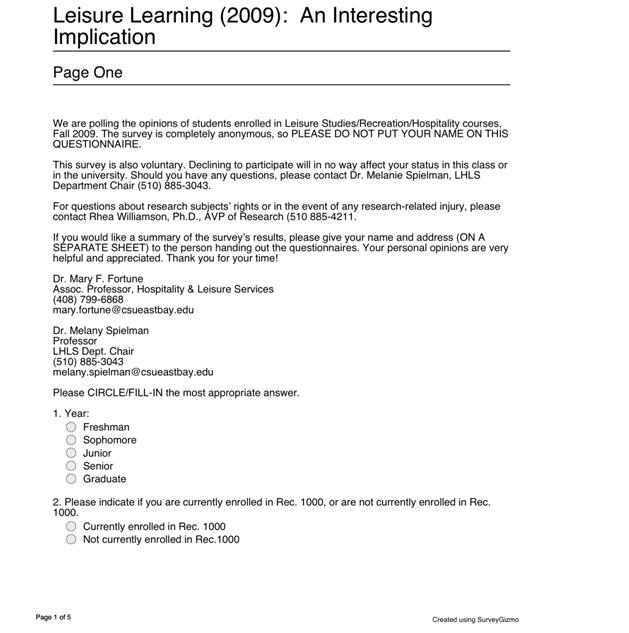

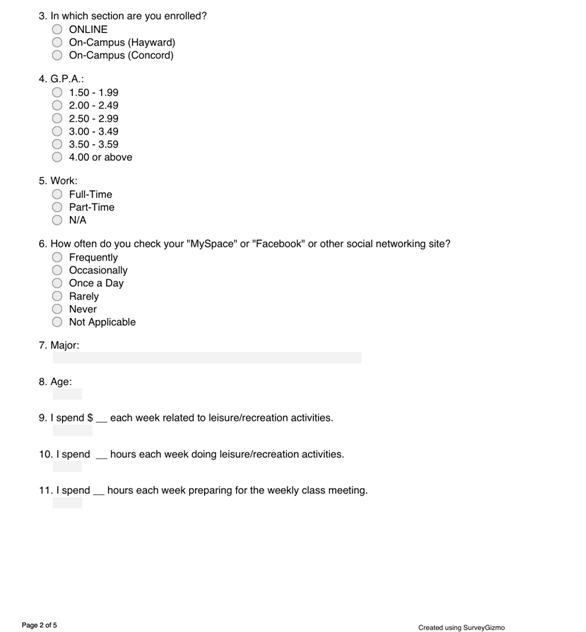

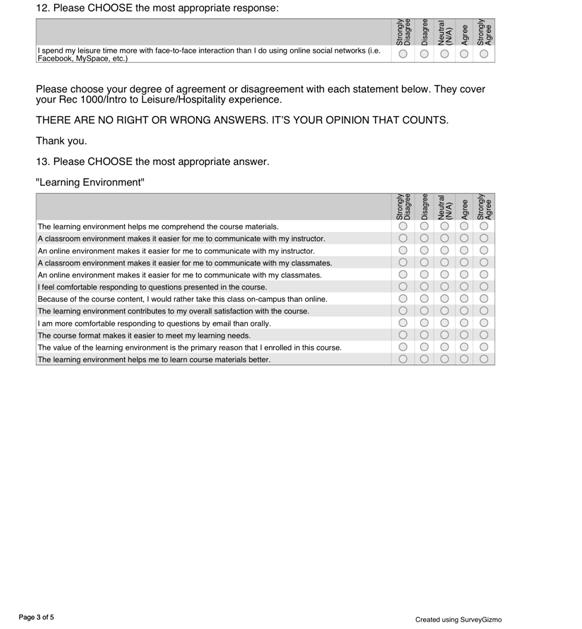

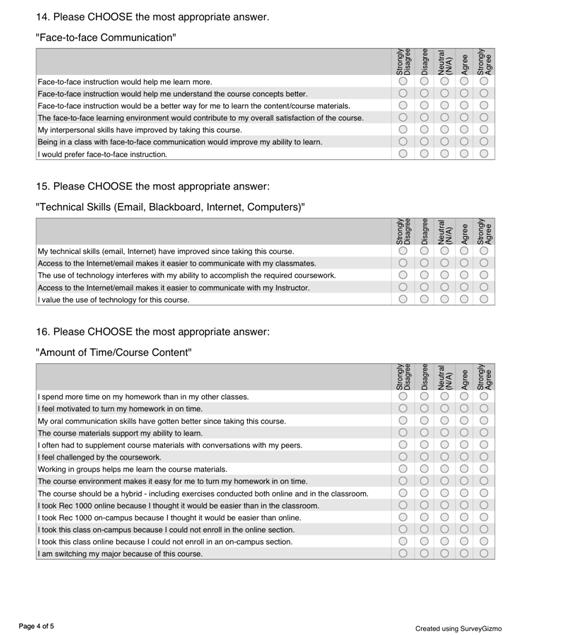

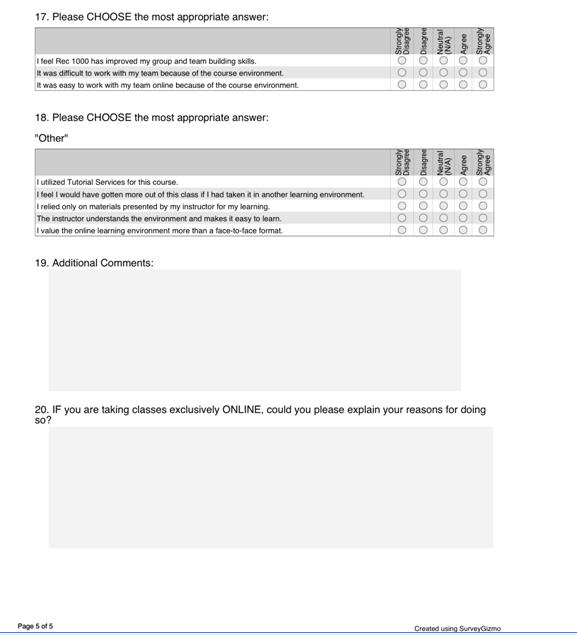

A pilot study was conducted using a survey developed and tested by Fortune, Shifflett, and Sibley (2006). The survey measured learning perceptions between students enrolled in online and F2F Business Communication courses. Building on the previous survey, the HRT survey was developed to measure learning perceptions and the use of leisure time. During the winter 2009 term, the HRT survey was piloted with students enrolled in both online and F2F sections of Recreation 1000/Introduction to Hospitality and Recreation, an introductory course that explores multi-disciplinary and multi-cultural dimensions of leisure. Students learn how leisure contributes to the quality of life of people and communities and the role it plays in a global society. The final HRT survey questionnaire was distributed to students enrolled in several sections of Recreation 1000 in spring 2009.

Participants

The participants in the study (n=156) were enrolled in either an F2F or an online section of the Recreation 1000 course. Students were given an equal opportunity to make that choice. The sample was representative of the population of the selected urban, multicultural university located in the Northern California.

Data Collection

The final HRT survey instrument consisted of 11 demographic, 47 five-point Likert-scale (strongly agree, agree, no opinion, disagree, and strongly disagree), and two free-form questions. The HRT survey was created using SurveyGizmo and was deployed online. An invitation was emailed to over 250 students enrolled in both the online and F2F sections of REC 1000 in spring 2009. Students enrolled in the course offered by the Department of Hospitality, Recreation, and Tourism were encouraged, but not required to take part in the HRT survey and the choice to participate or not had no impact on their grades.

As an open invitation list, no direct email communication occurred between the surveyors and the respondents. Furthermore, no duplicate responses were permitted as respondent keys were assigned to each independent respondent through the survey process. In all cases of significance testing, an alpha level of 0.05 was employed. The primary statistical software tools used for analysis were Microsoft Excel 2007 and SPSS (PASW) 17.

Results

Although more than 250 students participated in the HRT survey, almost 90 students abandoned the survey instrument in progress, leaving 156 viable and completed response sets. Of the 156 complete surveys, there was an almost uniform distribution of respondents among the four undergraduate class levels (freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior). Descriptive statistics show more than 77.6% of the sample was enrolled in an online section, with 17.9% (28 respondents) enrolled in an F2F environment. Almost consistently, each class level showed preference for the online course of instruction by a margin of 4-1, with juniors, the exception at roughly 3-1 (see Table 1).

Demographics

With regard to employment outside their academic study, 22.4% of the respondents reported that they were employed full-time and 41.7% of the respondents reported that they were employed part-time. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of full to part-time employed students and those enrolled online or F2F (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic Items

Item |

% |

Year |

|

Freshmen

|

22.4% |

Sophomores

|

26.3% |

Juniors

|

17.9% |

Seniors

|

25.0% |

Course Modality |

|

Online

|

77.6% |

F2F

|

17.9% |

Employment |

|

Full-time

|

22.4% |

Part-time

|

41.7% |

Age |

|

Freshmen

|

18-31 years |

Sophomores

|

19-52 years |

Juniors

|

20-59 years |

Seniors

|

21-50 years |

As reported by respondents, the top ten majors, in order of frequency, were Recreation, Business, Hospitality, Biology, Kinesiology, Nursing, Pre-Nursing, Biochemistry, Computer Science, and Accounting. The HRT majors accounted for 29.5% of all respondents, as this is a required core course for all the majors in the department. Since Recreation 1000 also meets a social science general education requirement, students from many other majors enroll in the course as well.

Hypothesis 1: No differences in perceptions of learning will be found when comparing the online and F2F modalities with students in REC 1000.

Results for Hypothesis 1: No difference in perceptions of learning was found in this student population when comparing the online and F2F course delivery.

The null hypothesis was supported: There are no differences in perceptions of learning between those enrolled in Recreation 1000 whether online or F2F. Even though no significant difference was found, four individual items did reach a level of significance at the .05 level.

A Kolmogorov-Smirnoff non-parametric test (at an alpha level of 0.05) showed a significant difference in learning perceptions between the two modalities and was due to the difference in sample sizes (77.6% online and 17.9% F2F). To determine more accurately if any differences did exist between the two groups (F2F and Online), a t-test (at the same alpha level) showed no statistically significant difference in their measures of central tendency.

Valuable information was revealed when each variable comparing the learning conditions was tested. The results are based on two-sided tests with significance level 0.05 using Pearson’s Correlation. Tests are adjusted for all Pairwise comparisons within a row of each innermost sub table using the Bonferroni correction. Of the 50 variables, only five items reached the 0.05 level of significance (see Table 2).

The following conclusions can be reached as a result of this survey: The students in the online modality felt that they were more comfortable asking questions than those in the F2F sections (r 2 =6.06, .014) and they often shared more than they would in a traditional F2F class because they felt more comfortable in speaking up.

The online students did not think that being in an F2F class would help them learn the materials any better. They would rather take a class online to learn the content and they prefer the online modality where they feel that they are able to learn best. They did not choose the online option as a backup solution for their academic career goals.

The students did not think that technology in an online class impacted their ability to learn. Many of these students grew up using technology in their daily lives and felt comfortable communicating online. Because technology has always been part of their lives, these “digital natives” (Prensky, 2001) use it seamlessly on an everyday basis.

The students in the F2F section appear to prefer F2F environments for communicating with instructors and would rather take the course on-campus because of the course content. They also significantly felt that that the F2F environment would help them to learn more, improve their understanding, and contribute to their satisfaction with the course. Additionally, they significantly preferred F2F instruction because they believe that this type of environment improves their ability to learn and that F2F is a better way for them to absorb the course materials.

F2F students found that the technology interfered with their ability to accomplish coursework and significantly felt that working in groups helped them to learn the course materials, but this did not rise to a level of significance. Note: F2F students also stated that they took the course “on campus” because they thought it would be easier than online, but they also felt that they would have gained more from the course if they had taken it in the online environment.

The online students felt that an online environment would have made it easier to communicate with their instructor and they were significantly more comfortable responding to questions by email than orally. They more often took the course online because they felt it would be easier than taking it in an F2F environment and felt that the course materials supported their ability to learn.

Online students also felt that the instructor understood the online environment and made it easy to learn, and they clearly valued the online environment more than the F2F modality. However, they were significantly split on whether it was easier or harder to work with their team online because of the online environment.

Hypothesis 2: Online social networking (OSN) is a leisure activity and students would rather communicate electronically (online) rather than face-to-face (F2F).

Results for Hypothesis 2: Participants spent more time in F2F interaction with friends than time online using OSN. They did report using Facebook (67.3% checked it at least once per day), but they did not believe that they spent more time online than F2F with their friends.

Hypothesis 2 is rejected because students believed they spent more time in F2F interactions with friends no matter how they were taking the class. A two-tailed z test was run to check the difference between the percentages of the two groups regarding preference for online social interaction over F2F. No significant differences were found.

Data showed that respondents spent an average of 15 hours per week engaged in leisure activities and an average of $40 per week on those same leisure/recreation activities, with the cost range spanning $0-200 per week. They also spent an average of 8 hours in preparation for weekly class meetings. Students clearly preferred F2F socializing in their leisure time, but spending time online also has a place in their world.

Table 2. Leisure Learning Survey Variables

Frequencies |

Correlations |

Item |

Agree |

Disagree |

Missing |

R2 |

df |

Sig |

A classroom environment makes it easier for me to communicate with my classmates. |

101 |

14 |

41 |

4.307 |

1 |

.038* |

I would prefer face-to-face instruction. |

51 |

42 |

63 |

4.413 |

1 |

.036* |

Face-to-face instruction would help me understand the course concepts better. |

76 |

29 |

51 |

6.060 |

1 |

.014* |

The use of technology interferes with my ability to accomplish the required coursework. |

39 |

74 |

43 |

5.317 |

1 |

.021* |

I feel challenged by the coursework. |

78 |

36 |

42 |

4.198 |

1 |

.040* |

Face-to-face instruction would be a better way for me to learn the content/course materials. |

62 |

37 |

57 |

3.262 |

1 |

.071 |

Face-to-face instruction would help me learn more. |

65 |

36 |

55 |

3.190 |

1 |

.074 |

I took Rec 1000 on-campus because I thought it would be easier than online. |

21 |

36 |

99 |

3.006 |

1 |

.083 |

The instructor understands the environment and makes it easy to learn. |

111 |

10 |

35 |

3.537 |

1 |

.060 |

The learning environment helps me comprehend the course materials. |

107 |

10 |

39 |

2.601 |

1 |

.107 |

Access to the Internet/email makes it easier to communicate with my classmates. |

98 |

18 |

40 |

2.419 |

1 |

.120 |

An online environment makes it easier for me to communicate with my instructor. |

60 |

31 |

65 |

1.902 |

1 |

.168 |

The face-to-face learning environment would contribute to my overall satisfaction of the course. |

52 |

42 |

62 |

2.306 |

1 |

.129 |

Being in a class with face-to-face communication would improve my ability to learn. |

57 |

42 |

57 |

1.851 |

1 |

.174 |

I took this class on-campus because I could not enroll in the online section. |

9 |

59 |

88 |

1.834 |

1 |

.176 |

* Statistical significance at the .05 level

Table 3. Online Social Networking vs. Face to Face

|

N |

Prefer Online |

Prefer F2F |

Z Score |

Z Critical |

F2F |

26 |

7 |

19 |

|

|

Online |

95 |

22 |

73 |

0.399 |

1.96 |

Discussion

Comparisons by group (online and F2F) were conducted to evaluate the differences in 1) perceptions of student learning regardless of the pedagogy/course environment, and 2) the use of leisure/recreation time related to online social networks. With respect to learning perspectives, there was no statistically significant difference between the participants enrolled in the online and F2F Recreation 1000/Introduction to Hospitality and Recreation classes. Students were very comfortable online and their mastery of the subject was not impacted by the use of a high tech environment. Many chose online over F2F classes for the convenience and ease of time and for the opportunity to work when they wanted instead of when they had to (Cuthrell & Lyon, 2007). Similarly, Harrington and Loffredo (2010) found that students preferred online courses because they were convenient and gave them the chance to being innovative and using computer technology. These students did not need the F2F environment to experience class participation (Artino, 2010).

It should be noted that in this study 77.6% of the students self-selected online course delivery, while only 17.9% preferred F2F delivery. Students chose their preferred course delivery during registration and each had an opportunity to take the Recreation 1000 course either online or F2F. The students choosing an F2F class were very firm on their preference, but it may simply be that it was the way they have always experienced being educated or socialized to “do” school. In fact, one student commented, “I would rather take on-campus classes. It is a better learning experience.” Another indicated, “I actually sat and spoke with my instructor, and I believe that he is better in F2F contact.” One online student commented, “I work full-time, however depending on the teacher there are times it would be nice to have the option in taking a F2F class.”

Students preferring online had similar motivations to the on-campus students. Both groups made the same assumptions that their preferred delivery style (online or F2F) was going to be “easier” and both groups believed that it would be easier to talk with the instructor and to ask questions in their preferred modality. One online student commented that “…it is more convenient for my schedule and because I am not so great on my communication skills.” Additional student comments included: “I took this class online because I did not think it was necessary to take it in a classroom environment.” “I take as many classes as I possibly can online.” “I live one and a half hours away from campus, have a family, and work full-time.” “I greatly appreciate online learning because I can do the coursework when I am able.” “I learn better when my learning is self-directed, and I am not stuck in a classroom.” “For me, F2F instruction is less conducive to learning than in an online environment.”

Another student summed up many of the benefits of online courses, “online learning has not only improved my typing, but has helped my reading, vocabulary, oral communication, and Internet skills (i.e. black board, horizon, good act.) I love online learning, I tell everyone to try it. I feel that I can communicate to my instructors better than if I was in class due to all the other classmates. As well as it does not give you busy work as most in class courses do. I am more confident in school and have better grades than ever.”

In this sample of students, 64% worked part or full-time. If the sample included only majors, the percentage of working students would be higher. If a student is successfully holding down a job in the industry while they are going to school, the need for professors to monitor their social interaction skills closely is lessened as a result of the applied learning environment and because they are developing and practicing their skills in their jobs. They are not only learning the required knowledge content but also practicing the work skills that they can only gain on the job. This synergy also plays a critical role in learning and strengthens the overall experience in higher education. As a result, online learning allows students to both earn a degree and gain valuable experience while working in the field.

Online Social Networking and Leisure Time

Students did use Facebook or other online services daily, but not for the amount of time assumed by the media (Young, 2009) and the belief that it did not have an impact on their grades. The accuracy of the self-report method used in this study cannot be verified, but students reported use is similar to that of the average user, according to Facebook, which states that the average user is on the site 45 minutes a day. This supports the self-report from the students (retrieved from Facebook, May 23, 2010). Furthermore, Pasek, More, & Hargittai (2010) found that their investigation into Facebook and its impact on grades determined that Facebook use did not significantly impact academic performance.

Extracurricular use of social networking as a means of learning is an interesting topic of study. Gemmill & Peterson (2008) suggest that the role of social networking and its relationship to academia needs to be explored further in order to assess the impact of social networking on student learning. They concluded that continual disruptions by technology hinder the focus on learning and distract students from the main goals of learning, which are to attain knowledge and graduate. Another possible effect has been on student scholarship levels (Martin, 2009). According to Karpinski (2009), college students who spend large amounts of time on Facebook tend to have lower overall GPA/grades but in a replication of Karpinski’s research, Pasek, More, and Hargittai (2009) found that there was no impact on college students’ grades due to Facebook use. Rutherford (2010) found that students are now using social media to work with classmates to prepare class assignments 60.2% of the time (very often and often), and also use it to complete assignments 54.2% (very often and often).

Conclusion

A survey instrument was distributed to students during the spring 2009 term to explore the value and impact of online learning environments in contrast to traditional classroom setting in a hospitality, recreation, and tourism course. The subjects provided the researchers with a clearer perspective regarding learning perceptions regardless of the teaching environment and the use of online social networking related to the HRT major. Even though the sample sizes were not equal, after controlling for differences in size, the HRT students did not differ in their perceptions of learning regardless their chosen mode of instruction.

Limitations

The vast majority of this sample self-selected whether they would take the class online or F2F. One way to mitigate the uneven groups would be to ask more sections of the F2F to participate in the next study. This could address one of the limitations of this present study. The main finding of this study was that students can learn in any type of environment and will gain new knowledge from their experiences regardless of the teaching modality.

To determine more accurately how much time students were involved in online social networking compared to academic learning, a tracking procedure could be employed. With more options now available for computer mediated social interactions, students have more distractions than ever. Self- reporting of time on electronic mediated social networking can be underreported.

Future Research

Future directions include expanding the study to use grades or success rates in the classroom to measure achievement to see if there are any differences in regards to teaching format (online or F2F) and how online social media impacts grades and graduation rates. A further study is planned to explore blended learning through the use of three sections of the same course, one online, one F2F, and one hybrid (one day online and one day in class) all taught by the same instructor in order to control for teaching style and ability. This study should produce new insights for professional educators.

References

ArtinoHigher Education, in press, August 2010.

Atan, H., Rahman, Z. A., & Idrus, R. M. (2004). Characteristics of the web-based learning environment in distance education: Students' perceptions of their learning needs. Educational Media International, 41(2), 103-110. Retrieved from Academic Search Premier.

Batts, D. (2008). Comparison of student and instructor perceptions of best practices in online technology courses. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 4, 477-489. Retrieved from https://jolt.merlot.org/vol4no4/batts_1208.htm.

Cuthrell, K. & Lyon, A. (2007). Instructional strategies: What do online students prefer? MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 3(4), December 2007. https://jolt.merlot.org/vol3no4/cuthrell.htm

Dervan, S., McCosker, C., MacDaniel, B., & O’Nuallain, C. (2006). Educational multimedia. In A. Méndez-Vilas, A. Solano Martín, J.A. Mesa González and J. Mesa González (Eds.), Current Developments in Technology-Assisted Education, Badajoz, Spain: Formatex, 810-805.

Facebook. (2010). In Facebook. Retrieved May 23, 2010, from http://www.facebook.com/ .

Fortune, M.F., Shifflett, B, & Sibley, R. A. (2006). A comparison of online (high tech) and traditional (high touch) learning in business communication courses in Silicon Valley. Journal of Education for Business, 81(4), 210-214 Mar-Apr 2006.

http://heldrefpublications.metapress.com/app/home/contribution.asp?referrer=parent&backto=issue,5,10;journal,29,80;linkingpublicationresults,1:119934,1.

Franzoni, A., & Assar, S. (2007). Using learning styles to enhance an e-learning system. Proceedings of the 6th European Conference on e-Learning, Copenhagen, Denmark: Academic conference management, 235-244.

Gemmill & Petterson (2008). Technology use among college students: Implications for student affairs professionals. NASPA Journal, 43 (2), 280-300. http://www.naspa.org.proxylib.csueastbay.edu .

Greenhow, C., Robelia, B., & Hughes, J. E. (2009). Research on learning and teaching with web 2.0: Bridging conversations. Educational Researcher, 38(4), 280-283. Retrieved from Sage Journals Online.

Harrington, R., & Loffredo, D. (2010). MBTI personality type and other factors that relate to preference for online versus face-to-face instruction. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 89-95.

Karpinski, A.C. (2009). A description of Facebook use and academic performance among undergraduate and graduate students. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, California, April 2009.

Larson, D., & Sung, C-H. (2009). Comparing student performance: Online versus blended versus face-to-face. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 13(1), 31-42, April 2009. http://www.sloanconsortium.org/node/1578

Martin, C. (2009). Social networking usage and grades among college students. UNH Media Relations, UNH Whittemore School of Business and Economics, December 23, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2010 from http://www.unh.edu/news/cj_nr/2009/dec/lw23social.cfm.

Pasek, J., More, E., & Hargittai, E. (2009) Facebook and academic performance: Reconciling a media sensation with data. First Monday, Peer-Reviewed Journal On The Internet, 14(5), May 4, 2009. http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2498/2181

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, MCB University Press, 9 (5), October 2001, 1-6. http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Rutherford, C. (2010). Using Online Social Media to Support Preservice Student Engagement. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 6(4), December 2010, 703-711. https://jolt.merlot.org/vol6no4/rutherford_1210.htm

APPENDIX

Appendix A

Appendix B

Leisure Learning And Social Networking: Online or

Face-To-Face? An Interesting Implication

Data

|

Frequencies |

Correlations |

Learning Environment

|

Agree |

Disagree |

Missing |

R 2 |

df |

Sig |

The learning environment helps me comprehend the course materials. |

107 |

10 |

39 |

2.601 |

1 |

.107 |

A classroom environment makes it easier for me to communicate with my instructor. |

69 |

27 |

60 |

.859 |

1 |

.354 |

An online environment makes it easier for me to communicate with my instructor. |

60 |

31 |

65 |

1.902 |

1 |

.168 |

A classroom environment makes it easier for me to communicate with my classmates. |

101 |

14 |

41 |

4.307 |

1 |

.038* |

An online environment makes it easier for me to communicate with my classmates. |

52 |

51 |

53 |

.985 |

1 |

.321 |

I feel comfortable responding to questions presented in the course. |

126 |

7 |

23 |

1.387 |

1 |

.239 |

Because of the course content, I would rather take this class on-campus than online. |

27 |

86 |

43 |

.961 |

1 |

.327 |

The learning environment contributes to my overall satisfaction with the course. |

99 |

7 |

50 |

.596 |

1 |

.440 |

I am more comfortable responding to questions by email than orally. |

76 |

26 |

54 |

1.099 |

1 |

.294 |

The course format makes it easier to meet my learning needs. |

98 |

8 |

50 |

.988 |

1 |

.320b |

The value of the learning environment is the primary reason that I enrolled in this course. |

74 |

27 |

55 |

.263 |

1 |

.608 a |

The learning environment helps me to learn course materials better. |

93 |

10 |

53 |

1.370 |

1 |

.242 |

Face to Face |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Face-to-face instruction would help me learn more. |

65 |

36 |

55 |

3.190 |

1 |

.074* |

Face-to-face instruction would help me understand the course concepts better. |

76 |

29 |

51 |

6.060 |

1 |

.014* |

Face-to-face instruction would be a better way for me to learn the content/course materials. |

62 |

37 |

57 |

3.262 |

1 |

.071* |

The face-to-face learning environment would contribute to my overall satisfaction of the course. |

52 |

42 |

62 |

2.306 |

1 |

.129 |

My interpersonal skills have improved by taking this course. |

60 |

30 |

66 |

.007 |

1 |

.934 |

Being in a class with face-to-face communication would improve my ability to learn. |

57 |

42 |

57 |

1.851 |

1 |

.174 |

I would prefer face-to-face instruction. |

51 |

42 |

63 |

4.413 |

1 |

.036* |

Technology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

My technical skills (email, Internet) have improved since taking this course. |

90 |

26 |

40 |

.022 |

1 |

.881 |

Access to the Internet/email makes it easier to communicate with my classmates. |

98 |

18 |

40 |

2.419 |

1 |

.120 |

The use of technology interferes with my ability to accomplish the required coursework. |

39 |

74 |

43 |

5.317 |

1 |

.021* |

Access to the Internet/email makes it easier to communicate with my Instructor. |

106 |

7 |

43 |

1.571 |

1 |

.210 |

I value the use of technology for this course. |

111 |

5 |

40 |

a |

a |

a |

Learning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I spend more time on my homework than in my other classes. |

65 |

36 |

55 |

.034 |

1 |

.853 |

I feel motivated to turn my homework in on time. |

114 |

11 |

31 |

.727 |

1 |

.394 a |

My oral communication skills have gotten better since taking this course. |

41 |

37 |

78 |

.160 |

1 |

.689 |

The course materials support my ability to learn. |

93 |

13 |

50 |

.495 |

1 |

.482 a |

I often had to supplement course materials with conversations with my peers. |

59 |

35 |

62 |

.115 |

1 |

.735 |

I feel challenged by the coursework. |

78 |

36 |

42 |

4.198 |

1 |

.040* |

Working in groups helps me learn the course materials. |

64 |

53 |

39 |

.019 |

1 |

.889 |

The course environment makes it easy for me to turn my homework in on time. |

95 |

10 |

51 |

.000 |

1 |

1.000 a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Preferences |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The course should be a hybrid - including exercises conducted both online and in the classroom. |

45 |

59 |

52 |

.002 |

1 |

.962 |

I took Rec 1000 online because I thought it would be easier than in the classroom. |

58 |

41 |

57 |

.346 |

1 |

.557 |

I took Rec 1000 on-campus because I thought it would be easier than online. |

21 |

36 |

99 |

3.006 |

1 |

.083* |

I took this class on-campus because I could not enroll in the online section. |

9 |

59 |

88 |

1.834 |

1 |

.176 |

I took this class online because I could not enroll in an on-campus section. |

14 |

75 |

67 |

.071 |

1 |

.789 a |

I am switching my major because of this course. |

14 |

98 |

44 |

.733 |

1 |

.392 |

Collaboration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I feel Rec 1000 has improved my group and team building skills. |

73 |

26 |

57 |

.653 |

1 |

.419 |

It was difficult to work with my team because of the course environment. |

41 |

62 |

53 |

.522 |

1 |

.470 |

It was easy to work with my team online because of the course environment. |

58 |

42 |

56 |

.302 |

1 |

.582 |

Overall |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I utilized Tutorial Services for this course. |

31 |

61 |

64 |

.723 |

1 |

.395 |

I feel I would have gotten more out of this class if I had taken it in another learning environment. |

35 |

68 |

53 |

.070 |

1 |

.792 |

I relied only on materials presented by my instructor for my learning. |

79 |

32 |

45 |

1.506 |

1 |

.220 a |

The instructor understands the environment and makes it easy to learn. |

111 |

10 |

35 |

3.537 |

1 |

.060* |

I value the online learning environment more than a face-to-face format. |

76 |

25 |

55 |

.076 |

1 |

.783 a |

a= More than 20% of the cells in this subtle have expected cell counts less than 5 Chi-square results may be invalid

* The Chi-square statistic is significant at the 0.1 level