Enhancing Pre-Service Teachers' Perceptions of Parenting:

A Glimpse into My Virtual Child

|

Shanna L. Graves

Assistant Professor of Early Childhood Education

School of Education

University Of Houston – Clear Lake

Houston, TX 77058 USA

gravess@uhcl.edu

Abstract

The benefits and challenges of technology-enhanced or virtual field experiences have been discussed in the literature related to teacher education. However, no previous studies seem to have explored the possibilities of the My Virtual Child program. The purpose of this paper is to provide a glimpse into My Virtual Child and share ways in which the program enhanced pre-service teachers' perceptions of parenting. Pre-service teachers enrolled in an undergraduate online Children and Families course shared their perceptions – via reflection papers – of the effectiveness of the My Virtual Child program in relation to understanding parenting. Results reveal that pre-service teachers felt the experience had a positive impact on their thinking about parenting. Specifically, pre-service teachers felt the My Virtual Child program: (1) forced them to think more critically about parenting decisions; (2) gave them a new perspective on parenting and its effects on children's development; and (3) had relevance to real-life situations. The My Virtual Child program was utilized as a virtual field experience in order to provide pre-service teachers with an opportunity to gain insight into parenting and its influence on child development. Hopefully, this new insight into parenting will positively impact pre-service teachers' ability to work with children's families.

Keywords: online simulation, e-simulation, virtual field experience, pre-service teacher education, parenting |

Introduction

Online learning has come a long way. Even in the last five years, with a plethora of technological advances, online learning has become a major instructional environment (Salem, 2012). The number of students enrolling in online courses continues to grow, as distance education has now become a worldwide phenomenon (Ambient Insight, 2012; Murray, Pérez, Geist, & Hedrick, 2012). As institutions of higher education in the United States become more accepting of online education, they will be met with the task of providing high-quality online programs (Kim & Bonk, 2006). In order to meet the needs of students – especially those who are "non-traditional" – higher education institutions must continuously look for ways to best use technology for students at all levels (undergraduate and graduate), as well as in a variety of formats, including face-to-face and hybrid (Rose, 2009).

The integration of technology in pre-service teacher education is the focus of this paper. While countless research exists on the myriad instructional strategies utilizing technology in teacher education programs, none seem to have explored the possibilities of My Virtual Child. This paper intends to shed some light on the ways in which My Virtual Child can enhance pre-service teachers' perceptions of parenting. My Virtual Child was incorporated into a fully online Children and Families course for pre-service teachers. At the end of the course, the pre-service teachers reflected on their experience using the My Virtual Child program. The pre-service teachers' perceptions on the effectiveness of the program as it was incorporated into the course will be discussed in this paper.

Literature Review

The Growth of Online Learning

The most recent data related to the growth of online learning reveals a number of interesting findings. In their most recent report on the state of online learning in U.S. higher education, Allen and Seaman (2011) found that 31% of students in higher education are now taking at least one online course. Further, the research firm Ambient Insight recently released a 2012 snapshot of the Worldwide and U.S. Academic Digital Learning Market and found a steep decline (more than 22%) in the number of students taking all of their classes in a physical classroom environment. The firm forecasts that by the year 2016, more than 23 million students in higher education will be taking at least one online course while less than 3 million students will be taking classes exclusively in a physical classroom environment (Ambient Insight, 2012). It may be important to note that the growth rate of online learning has slowed; however, it remains in excess of the rate of the total higher education student population (Allen & Seaman, 2011).

Researchers have shown interest in the reasons why online learning is increasing in higher education (Castle & McGuire, 2010; Dobbs, Waid, & del Carmen, 2009). According to Castle and McGuire, there are several reasons, including:

its potential to provide flexible access to content and instruction at any time, from any place and cost-effectiveness for institutions of higher education. Online learning can increase the availability of learning experiences for learners who cannot, or who choose not to, attend traditional face-to-face (onsite) offerings, it offers an opportunity to disseminate course content more cost-efficiently, and also enables higher student to faculty ratios while maintaining a level of outcome quality equivalent to face-to-face instruction. (p. 36)

Dobbs et al. (2009) suggests that the increase in online learning can be attributed to the affordability and accessibility of technology. Essentially, today's students have more direct access to computers and the Internet than ever before.

Even with the increase in online learning, there remains some skepticism in regards to the true potential of online learning, particularly when compared to face-to-face instruction. Allen and Seaman (2011) found little change among academic leaders (e.g., chief academic officers) in their perception of the relative quality of online learning as compared to face-to-face instruction. Further, academic leaders' perceptions of faculty acceptance of online versus face-to-face instruction have remained constant since 2003. Less than one third of the leaders believe their faculty accept the value and legitimacy of online education. Research has shown, however, that online learning can be as effective as other modes of instruction as long as the courses are well designed, provide access to high quality instructional materials, and are led by experienced and motivated faculty (Mayadas, Bourne, & Bacisch, 2009; Murray et al., 2012). In Mayadas et al.'s analysis of data provided by a number of institutions, they found that the quality of education received by online students and students in traditional classes was equivalent, and the dropout rates were the same. It may also be important to note that perceptions of the value of online learning vary by the type of school (Allen & Seaman, 2011), as well as the faculty background and experience with online teaching (Lao & Gonzales, 2005).

Online learning in higher education is a relatively broad topic, thus there is an abundance of research available. Higher education, though, encompasses many vastly different areas – from business to engineering to teacher education. With the advancement of virtual schools in K-12 education, it seems that online learning in teacher education is as common a research topic as any other area in higher education. Further, since a major component of teacher education programs is field experience, or practica, it seems obvious that research on the integration of technology in field experiences would be copious. The final section of this literature review focuses on online learning and its possibilities within field experiences in teacher education programs.

Integration of Technology in Field Experiences

There has been much discussion in the literature on the benefits and/or challenges of technology-enhanced field experiences (Brown, 1999; Ferry, Kervin, Cambourne, Turbill, Hedberg, & Jonassen, 2005; Foley & McAllister, 2005; Girod & Girod, 2008; Hixon & So, 2009; McPherson, Tyler-Wood, McEnturff, & Peak, 2011; Payr, 2005). A common thread in this discussion is the notion of "safety in practice." For example, Brown believes that:

field work does not allow enough room for error; it's not possible to redo a botched activity with real and very vulnerable school-age children. Learning through play simulation has at least one advantage over learning in situ, and learning in this manner is natural to humans. (p. 308)

Brown (1999) goes on to argue that if the play instinct is a basic component of human development and thought, then simulation deserves more attention as an instructional activity in teacher education. Girod and Girod (2008) believe that in order for practice to be effective, among other things it should provide a setting for candidates that will enable them to experiment and fail safely. The researchers believe failure in a practicum setting could be destructive.

The idea of simulation as a teaching, or educational, tool is nothing new and is not limited to teacher education. Major agencies such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) have been known to use virtual reality technology to train mission operations flight control and engineering personnel (Brown, 1999). Teacher education programs certainly have the potential to experience such success with simulations, as revealed in the literature on virtual field experiences. For example, Foley and McAllister (2005) conducted research on Sim-School, a web-based simulation of a classroom in which candidates:

experience pre-service education courses through a hands-on approach in which they must apply to a school, receive a classroom with simple profiles of their students, and then complete a series of assignments as a member of a grade level team and school faculty. (p. 160)

The findings from the Sim-School study revealed that students felt the simulation helped them feel prepared and confident about student teaching, as well as more engaged in the course content because they were able to apply theory to practice in their simulated classrooms.

Hixon and So (2009) found that what works best actually depends on what candidates need to learn from the experience. The researchers believe that virtual field experiences may be more useful as a tool to help students make the connection between theory and practice. Similarly, Ferry et al. (2005) suggest that simulated environments are simply alternative ways to exhibit a theoretical perspective in action, but within a virtual classroom.

As previously stated, perceptions of the value of online learning and, for that matter, virtual field experiences vary. As such, it is critical that instructors continue to share effective online strategies and experiences in order to challenge the notion that online learning might be inferior to face-to-face learning and, therefore, may have no place in teacher education. Every day there are technological advances that break the barrier between certain pedagogical strategies and online delivery. Therefore, the immeasurable potential of online learning cannot – and should not – be understated. The intention of this paper is to share pre-service teachers' experience utilizing a virtual simulation program as a means to gain experience in the world of parenting and to make those connections between the program and course content related to children and families.

My Virtual Child

My Virtual Child, a virtual "parenting" simulation program, was created by Frank Manis at the University of Southern California in 2007. The program can be used in different types of courses as well as in different formats (i.e., face-to-face, hybrid, online). After purchasing the program, students create a log-in username and password. Students must then complete registration, which includes identifying the parents' gender, choosing the child's physical characteristics, and completing cognitive and personality quizzes.

The quizzes include Likert-type items and require students to rate their own personality when they were between the ages of 16 and 18, as well as their abilities in five multiple intelligence areas (verbal, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, and bodily-kinesthetic).

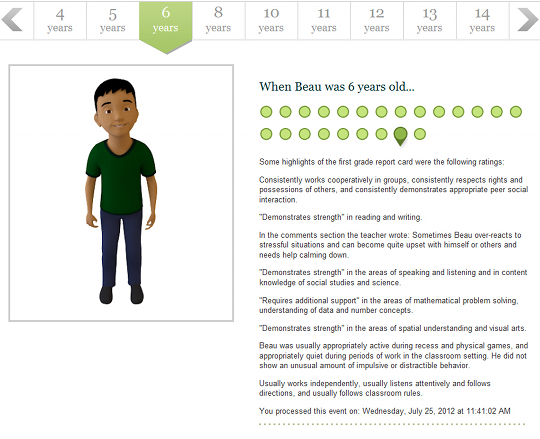

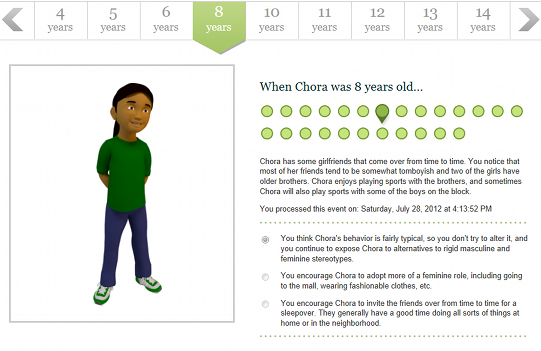

"Once the initial student choices are made, the program 'tells the story' of the development of this child up to 18 years of age" (Manis, 2011, p. 5). Each child in the virtual program is unique and its development is affected by a number of factors, including the child's and parent's personality characteristics at birth, parenting decisions, and random environmental occurrences (Manis, 2011). As students progress through the program, they observe their child's developmental progress; they receive reports from the pediatrician and psychologist, as well as school report cards (see Figure 1). Detailed information about the child's behavior is described through events and questions (see Figure 2). Events may include developmental milestones and questions provide scenarios that require the student to make choices that will ultimately affect their child's life trajectory (Manis, 2011). Once students have completed the entire program, they will have made 275 parenting decisions.

Figure 1. Example of a school report card

Figure 2. Example of a scenario

Context of the Course

The My Virtual Child program (second edition) was incorporated into a fully online Children and Families course for pre-service teachers and was the designated "virtual field experience" for the course. Field experience is a requirement for the 16-week course (which is generally taught face to face), and in past semesters, the field experience ranged from volunteering at non-profit organizations that worked closely with children and families (i.e., a child care center in a battered women's shelter) to simply visiting various community programs that provided outreach to children and families experiencing a variety of family stressors. The intention behind the decision to incorporate My Virtual Child as the field experience was to have pre-service teachers focus more specifically on various aspects of parenting and its effects on children's growth and development. Some of the course objectives that specifically tie – in one way or another – into My Virtual Child include the following:

- Analyze the relationship of the family to a child's social and emotional development;

- Analyze the influence of environmental factors on a child's social and emotional development;

- Develop an understanding of factors affecting the development of self-concept, independence, and pro-social behaviors;

- Understand the role of parental involvement in education.

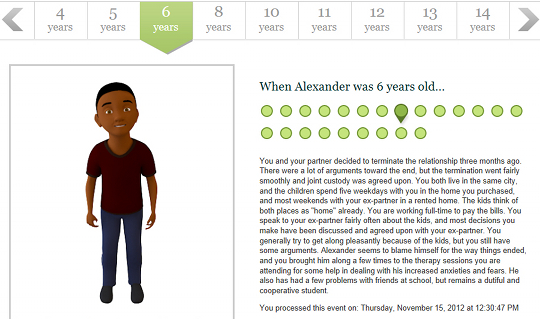

Field experience was one of many course requirements, but the My Virtual Child program was not completely separate from other aspects of the course. Many of the discussions from the chapters in the course textbook, Families, Schools, and Communities: Together for Children (Couchenour & Chrisman, 2011), were reiterated in either videos or scenarios in the My Virtual Child program. For example, the course's weekly discussion board activities included topics such as economic differences between families, the stress of divorce, and the challenges of balancing work and family. In the My Virtual Child program, many of the pre-service teachers were faced with environmental occurrences, such as the loss of a spouse's job and subsequent changes in living arrangements (moving from home to apartment), termination of the relationship with their spouse, and the realities of single motherhood (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Example of an environmental occurrence

The pre-service teachers were required to complete the My Virtual Child program before the course ended. As stated previously, there are approximately 275 parenting decisions that must be made by the end of the program so the pre-service teachers were advised to carefully pace themselves throughout the semester. There was no set schedule for progressing through the program. The pre-service teachers were given freedom to work at their own pace, as long as the program was completed by a set deadline.

Method

Nineteen female pre-service teachers were enrolled in the Children and Families undergraduate course, which was offered in a fully online format for the first time at the university. None of the pre-service teachers had participated in any type of virtual field experience prior to this course. The instructor was able to track the pre-service teachers' progress in the My Virtual Child program through the Student Roster in the program. Students were required to input a designated Class ID during registration and their information was then transferred to the roster that was only visible to the instructor.

In addition to completing the program, the pre-service teachers were required to share their "parenting" experiences with their classmates. The instructor created a Parent Forum on the course discussion board (see Figure 4) and the pre-service teachers were required to post updates on their virtual child and respond to their classmates' posts as well. The Parent Forum was created as a means to make this experience as peer interactive as possible.

Figure 4. Screenshot of the Virtual Child Parent Forum

Upon completion of the My Virtual Child program, the pre-service teachers were required to submit a reflection paper detailing their experience as a virtual parent and their perceptions of the value of this virtual field experience. The reflection papers followed a Describe–Analyze–Plan (DAP) format. First, the pre-service teachers were to provide a detailed description of their virtual child, including personality characteristics, behavioral patterns, and cognitive and social-emotional developmental patterns throughout the child's life. Second, the pre-service teachers were to critically analyze their experience as a virtual parent and describe how this virtual field experience may have changed their perception of parenting in any way. Additionally, the pre-service teachers were to critically analyze their own personality, interests, and developmental pattern and note whether there were any similarities between themselves and their virtual child. Finally, the pre-service teachers were to offer their critical thoughts on this virtual field experience, including positive and negative aspects. The pre-service teachers were also asked to offer suggestions for future use of this program to help the instructor in planning for future courses.

The pre-service teachers uploaded their DAP reflection papers to the learning management system at the end of the course. The instructor then printed all of the papers and read them several times, looking for central themes. Keywords were highlighted and notes were made in the margins of the papers. Similar phrases and/or quotes were grouped together and rearranged until separate, distinct themes were identified. Additionally, the instructor went back and read through the pre-service teachers' posts to the Virtual Child Parent Forum in order to get a sense of the pre-service teachers' experiences as virtual parents and their feelings about the program.

Student Perceptions

Overall, the feedback about the virtual field experience was positive. Some of the responses (from the DAP reflection papers) included: "very interesting"; "one of the greatest assignments I have ever been assigned"; "positive experience"; "my favorite assignment"; "the best ever!"; "the field experience was one of my favorite parts about this class"; "great asset to this class"; "made the greatest impact"; "very enlightening"; "an eye opener"; "great tool"; "very educational and well-developed"; and "excellent learning experience for me."

Three main themes emerged through analysis of the DAP reflection papers, indicating that the My Virtual Child program did enhance pre-service teachers' thinking about parenting.

Critical Thinking

The majority of pre-service teachers revealed that the program forced them to think more critically about parenting and the effects of making certain decisions. At various points in the program, pre-service teachers were given choices about a plethora of issues, such as how to intervene in their child's academic development. For example, if they had a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), they would be presented with choices about the use of medication and behavior management at home and at school (Manis, 2012). As one pre-service teacher stated, "I like the choices it gives you on the actual program, it makes you think. There were multiple questions that I had to sit back and think about. This program really showed me a lot that goes into parenting that I have never thought about before." Another pre-service teacher noted that the program helped her think more critically and forced her to reflect on her real-life parenting. She said:

"My Virtual Child allowed me to think away from my usual mom decisions, and go into more critical thinking. I had to think about my choices and watch how it affected the child I was raising. It was scary and impressive. It was scary because it really made me realize just how much my decision as parent and person around my daughter all the time, affects her life. It was impressive because it was just so accurate on my personality and my daughter's. It made me realize that my daughter's attitude and person is being shaped by everything I do and say."

A New Perspective

Many of the pre-service teachers' reflection papers discussed how the My Virtual Child program gave them a new perspective on parenting. From the beginning of the program, the pre-service teachers were presented with questions and events that forced them to consider everyday challenges many parents face in real life. For example, some of the events the pre-service teachers experienced included, but were not limited to, an unexpected second pregnancy, separation from partner, temper tantrums, partner getting laid off from work, transitions in child care, moving to a new home or apartment, and attachment issues. As revealed in their responses, the pre-service teachers experienced a few eye openers through their participation in the My Virtual Child program. Examples of some of the responses are revealed below:

"It made me think of topics that I have never taken into consideration. It showed me that there is so much to raising a child and so many decisions to be made throughout the process ... it really put into perspective all the changes that have to be made in life once having a child."

"My Virtual Child helped me realize how parents, adults, and a child's environment can greatly affect how a child develops. I never understood how much impact each decision would be on a child. I learned that every decision a parent makes would determine how that child would turn out to be."

"It brought up points that I have never thought of such as, would I allow my baby to play with objects more than be around people, and what would I do if my child is more attached to me than to my husband. I started to get so into the program that when my child did well I would feel so proud of her."

"The experience changed a lot of the pre-conceived notions that I had about what it would be like to raise a child. Parenting seems hard from afar, but is a lot harder when you have to make decisions that can affect the well being of a human being."

Real-World Application

Approximately half of the pre-service teachers in the course were real parents. The reflection papers, however, revealed that regardless of their experience as real parents, the pre-service teachers could envision the program's applicability to real life. The questions and events that were presented throughout the program were realistic and did not include any extraordinary or inconceivable scenarios. The pre-service teachers discussed how they thought of real life as they navigated through the program and some even stated that they would use some of the knowledge gained in the program in their future parenting. For example, one pre-service teacher said, "It gave me some confidence in my future decision making as a parent." Other similar responses included the following:

"As the program progressed I really tried to envision how I would handle the scenarios in the real world. [My] Virtual Child made me really aware of how parenting style affects a child's development. I hope to use my knowledge from the [My] Virtual Child program to become a better parent toward my daughter."

"I thoroughly enjoyed the virtual field experience. I felt that it provided a great opportunity for non-parents (like myself), to get a glimpse of what it would be like to be a parent. The field experience had several scenarios and situations that a parent could possibly face with their actual children."

"My parenting style will most likely be like the one I used with My Virtual Child ... it really made me think about the type of parent I am going to be and how I will deal with situations that affect my children."

"I often considered what I would do in a real world scenario and tried to answer each question as honestly as I could. I learned a lot about myself and I learned that parenting takes a lot of adaptation."

"My husband found my "virtual child" very interesting. He actually sat with me a couple of times and made some decisions with me. We discussed our decision and it is nice to be reassured that we do agree on some things about raising a child. I suppose that was practice!"

Discussion and Conclusion

The pre-service teachers' perceptions of the My Virtual Child program were positive. After participating in this virtual field experience, pre-service teachers discussed its impact on their thinking about parenting. The majority of pre-service teachers felt that the My Virtual Child program: (1) forced them to critically think about parenting decisions; (2) gave them a new perspective on parenting; and (3) had relevance to real-life situations. These results reveal that the My Virtual Child program can, in some ways, enhance the online experience for pre-service teachers. Whether instructors choose to use the program as a supplement to course material or as a virtual field experience, My Virtual Child has the potential to enrich the teaching and learning experience in positive ways.

As stated earlier in the Literature Review, what works best – in terms of virtual field experiences – actually depends on what candidates need to learn from the experience (Hixon & So, 2009). In this particular situation, the instructor wanted to provide pre-service teachers with a different type of "field" experience. This Children and Families course has been designed to provide insight into all environmental factors that affect the whole child – school, family, and community. As stated before, previous field experiences have focused on the community's influence (i.e., visiting various community programs), as well as a school's influence (i.e., volunteering at a childcare center in a battered women's shelter), on children's growth and development. This time, the instructor wanted to offer an experience that would allow pre-service teachers to focus more on the parental influences on a child's growth and development.

Perhaps this new insight into parenting and its influences on children can affect pre-service teachers' thinking about parental involvement in education. For example, when a teacher has a deeper understanding of the many challenges of parenting, he/she will more likely sympathize with the parents and demonstrate a level of sensitivity to the family's issues. A major part of teaching is developing partnerships with children's families, and the preface to that is simply understanding the many challenges parents face. Perhaps more important than learning how to teach content is learning how to work collaboratively with children's first teachers – their parents. To that end, a simple glimpse into the world of parenting could be a transformative experience for pre-service teachers.

Brown (1999) believes that simulations have established some credibility as instructional activities and states that "in teacher education, the possibility of creating environments in which pre-service teachers may experiment with a variety of decisions and their outcomes without placing any real students at risk should be an exciting prospect" (p. 316). As revealed in this paper, the My Virtual Child program does hold potential as a credible instructional activity in teacher education. The pre-service teachers who participated in the program expressed excitement at learning in a new way. Some of them admitted to being hesitant initially, but revealed that they quickly saw the value in using this program as a teaching tool in an online course.

Although the results of this study have focused primarily on the pre-service teachers' perceptions of parenting, the My Virtual Child program did touch on several issues that were discussed in this course throughout the semester. Through its scenarios and videos, the program provided opportunities for the pre-service teachers to look at how certain parenting styles or behaviors can affect a child's self-concept, independence, and pro-social behaviors, but the program also provided insight into how changes in the family (i.e., divorce, loss of job, relocation to a different community) can affect a child's social and emotional development, and how a number of environmental factors influence a child's growth and development in different ways.

There are limitations to this study that should be noted. While a new perspective of parenting was a specific objective of the course, it did emerge as a theme. This could have been the result of the writing prompt that was used for the reflection papers. The guidelines for the reflection paper were very specific and perhaps did not leave room to explore other perspectives on the program. Given the fact that the My Virtual Child program tied into several of the course objectives, opportunities to analyze this program in multiple ways, from different angles, could have explored. For example, it may have been useful to develop research questions that related more specifically to all of the course objectives that tied into the My Virtual Child program. In this way, the effectiveness of the My Virtual Child program in meeting the course objectives could have been explored. Additionally, this approach could have provided further insight into how this program relates to other issues in teacher education.

Suggestions for future research into the My Virtual Child program include a more critical analysis of different aspects of the program. As stated previously, this program can be used in a variety of courses and in different formats. As such, there are countless opportunities to dissect this program. The purpose of this paper was to provide a glimpse into one aspect of the program, but a deeper, more critical analysis is needed and may prove useful, particularly in teacher education.

References

Ambient Insight. (2012). 2012 snapshot of the worldwide and US academic digital learning market. Monroe, WA: Author. Retrieved from http://www.ambientinsight.com/Resources/Documents/AmbientInsight-2012-Snapshot-Worldwide-US-Academic-DigitalLearningMarket.pdf

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2011). Going the distance: Online education in the United States, 2011. Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group. Retrieved from http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/goingthedistance.pdf

Brown, A. H. (1999). Simulated classrooms and artificial students: The potential effects of new technologies on teacher education. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 32(2), 307-318.

Castle, S. R., & McGuire, C. J. (2010). An analysis of student self-assessment of online, blended, and face-to-face learning environments: Implications for sustainable education delivery. International Education Studies, 3(3), 36-40. Retrieved from http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ies/article/download/5745/5308

Couchenour, D. L., & Chrisman, K. (2011). Families, schools, and communities: Together for young children (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Dobbs, R. R., Waid, C. A., & del Carmen, A. (2009). Students' perceptions of online courses: The effect of online course experience. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 10(1), 9-26.

Ferry, B., Kervin, L., Cambourne, B., Turbill, J., Hedberg, J. G., & Jonassen, D. H. (2005). Incorporating real experience into the development of a classroom-based simulation. Journal of Learning Design, 1(1), 22-32. Retrieved from https://www.jld.edu.au/article/download/5/3

Foley, J. A., & McAllister, G. (2005). Making it real: Sim-School a backdrop for contextualizing teacher preparation. AACE Journal, 13(2), 159-177. Retrieved from EdITLib Digital Library. (5955)

Girod, M., & Girod, G. R. (2008). Simulation and the need for practice in teacher preparation. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 16(3), 307-337. Retrieved from EdITLib Digital Library. (24469)

Hixon, E., & So, H.-J. (2009). Technology's role in field experiences for preservice teacher training. Educational Technology & Society, 12(4), 294-304. Retrieved from http://www.ifets.info/journals/12_4/25.pdf

Kim, K.-J., & Bonk, C. J. (2006). The future of online teaching and learning in higher education: The survey says ... . EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 29(4), 22-30. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/future-online-teaching-and-learning-higher-education-survey-says%E2%80%A6

Lao, D. T., & Gonzales, D. C. (2005). Understanding online learning through a qualitative description of professors' and students' experiences. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 13(3), 459-474. Retrieved from EdITLib Digital Library. (4692)

Manis, F. (2011). My Virtual Child: An instructor's manual. Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California.

Mayadas, A. F., Bourne, J., & Bacisch, P. (2009). Online education today. Science, 323(5910), 85-89. doi:10.1126/science.1168874

McPherson, R., Tyler-Wood, T., McEnturff, A., & Peak, P. (2011). Using a computerized classroom simulation to prepare pre-service teachers. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 19(1), 93-110. Retrieved from EdITLib Digital Library. (31438)

Murray, M., Pérez, J., Geist, D., & Hedrick, A. (2012). Student interaction with online course content: Build it and they will come. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 11, 125-140. Retrieved from http://www.jite.org/documents/Vol11/JITEv11p125-140Murray1095.pdf

Payr, S. (2005). Not quite an editorial: Educational agents and (e-)learning. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 19(3/4), 199-213. doi:10.1080/08839510590910147

Rose, K. K. (2009). Student perceptions of the use of instructor-made videos in online and face-to-face classes. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 5(3), 487-495. Retrieved from https://jolt.merlot.org/vol5no3/rose_0909.htm

Salem, N. M. (2012). Online learning: Determinants of success. In P. Resta (Ed.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2012 (pp. 853-858). Chesapeake, VA: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education. Retrieved from EdITLib Digital Library. (39679)