It's Showtime: Using Movies to Teach Leadership in Online Courses

|

Maureen Hannay

Professor

Sorrell College of Business

Troy University – Global Campus

Troy, AL 36802 USA

mhannay@troy.edu

Rosemary Venne

Associate Professor

Edwards School of Business

University of Saskatchewan

Saskatoon, SK S7N 5A7 CANADA

venne@edwards.usask.ca

Abstract

Online learning is now widely recognized and accepted as a viable alternative to face-to-face teaching. It has opened up learning opportunities for people of many ages in many different locations that previously did not have access to a wide range of educational choices. The continuing challenge is to ensure that online courses embrace the best of both worlds, combining the flexibility and accessibility afforded by the electronic format with the benefits of interaction and communication as seen in the face-to-face classroom. Carefully choosing movies that demonstrate course concepts and integrating them into the online course curriculum provides an excellent platform for learner–learner exchange and engagement and can increase communication and collaboration among participants. This paper recommends the movie Twelve O'Clock High as one choice for enriching the online learning experience for students studying leadership as it provides clear representations of theoretical concepts and examples of effective and ineffective leadership behavior.

Keywords: film, learner–learner interaction, collaborative learning, virtual teams, teaching tools, course enrichment |

Introduction

After several years of growing pains, which included resistance from faculty, students, and administrators, online courses seem to have secured a solid foothold in post-secondary education, and they continue to be on the rise. The 2010 Sloan Survey of Online Learning surveyed more than 2,500 American colleges and universities and found that approximately 5.6 million students were enrolled in at least one online course in Fall 2009, with nearly 30% of all U.S. college and university students now taking at least one such course (Allen & Seaman, 2010). This represents the largest ever year-to-year increase, with the 21% growth rate for online enrollments far exceeding the 2% growth in the overall higher education student population. Three quarters of institutions report that the economic downturn has actually increased the demand for online courses and programs. Ambient Insight (a research firm focusing on global e-learning) forecasts that 18.65 million college students will take at least some of their classes online by 2014 (cited by Nagel, 2009). Online courses appear to be an ideal way for universities to maximize enrollment beyond their traditional markets. This can be especially important for institutions in rural areas that are striving to meet the needs of students who are often geographically "fixed" and unable to relocate to fulfill their educational goals due to family, employment, and/or financial limitations.

As increased numbers of learners turn to online education for personal and professional development, the nature of the online environment poses significant challenges to the development of online learning communities (Johnson, 2007). To ensure that the online learning environment is as effective as the live classroom (and perhaps ultimately offers more than can be delivered in the traditional learning environment), it is important to address the lack of face-to-face interaction and real-time dialogue among students, which can be a significant shortcoming in poorly structured online courses (Johnson, 2007). In this position paper, an approach for building interactivity by using movies in an online leadership course is proposed. Learner–learner interactions are key in a leadership course as sharing students' experiences with effective and ineffective leadership can play a significant role in the learning process. This is particularly true at the graduate level, where students have often been in leadership roles themselves and can relate their own experiences as both leaders and followers. The use of film can provide a means to generate interactivity and at the same time provide vivid models of both effective and ineffective leadership behavior. This paper demonstrates the use of film as a teaching tool in online courses to build learner–learner interactions using Twelve O'Clock High, a movie that contains strong leadership elements and themes. It discusses the logistics of using movies and provides examples of the application of leadership theory to movies.

Moving from Face-to-Face to Online and Beyond

Most aspects of the face-to-face classroom experience can be effectively translated into the online learning environment by embracing interactivity between the students and the instructor and among the students themselves. Interaction plays a significant role in differentiating online courses from old-fashioned correspondence courses. The instructor must develop strategies to ensure that students' experiences in the online environment are at least equivalent to those they would have in the face-to-face classroom, because online students will be held accountable for possessing the same level of knowledge of the course materials as their campus-based counterparts. However, with the application of specific strategies to encourage interactivity and critical thinking, online learning may generate opportunities for students to experience a learning environment that does not just imitate the physical classroom, but rather capitalizes on the online medium to deliver a more comprehensive learning experience.

In her article "From Sage on the Stage to Guide on the Side," King (1993) discusses how instructors, as guides, can facilitate learning in less directive ways. She notes that in this model, students have to actively participate in thinking and discussing ideas while creating meaning for themselves. Palloff and Pratt (2001) maintain that the online environment is conducive to an interactive, collaborative, and facilitated approach wherein the instructor acts as a guide to the process rather than its director. Further, Palloff and Pratt tell us that through the development of a learning community, students can undergo their greatest and most profound learning through reflection and interaction with one another. Indeed, from a study of online group discussions, students indicated that critical-thinking skills were enhanced when working collaboratively, and they found the achievement of course goals easier and more efficient (Du, Durrington, & Mathews, 2007).

Some educators posit that this facilitative role does not mean that the instructor is doing less; actually, more is required. For example, Taormino (2012) notes that to facilitate effective individualized learning, the provision of timely feedback is necessary. He goes on to point out that the "guide-on-the-side" approach places the student at the center of learning, where the instructor can be much more involved with the student's experiences than is possible with a lecture-hall format. When students are encouraged to embark on a process of discovery during facilitated online courses, the resulting outcome is a deepening of the learning experience (Palloff & Pratt, 2001). Here, the essence of online learning can help move the learning process beyond what might be experienced in a traditional classroom setting.

The instructor as a guide and the fostering of a learning community are entirely consistent with the goals of a course in the area of leadership. Developing leadership skills is a process of discovery, and each student will likely make those discoveries in different ways and at different rates. Therefore, teaching leadership as an online course with the instructor as the facilitator and students building learning communities through conversation and interaction seems to be a logical fit.

Yet perhaps the most important lesson that can be taken from this analysis is that the pinnacle of online learning should not simply be replicating the traditional face-to-face classroom. An effort should be made to employ the tools available in the virtual classroom to provide students with a deeper and richer learning experience. The online instructor can guide students through the process of self-learning through discussion threads that may stretch over several days – allowing for reflection and interaction, identified as key learning elements by Palloff and Pratt (2001) – rather than being limited by the length of a class period. All students, as opposed to just a handful of them as we often find in the traditional classroom, can be required or given the opportunity to participate in the discussion, thereby increasing its breadth.

Online learning demands strong self-discipline, sound time-management skills, and the ability to motivate one's self. In other words, effective online learners must first be able to lead themselves in order to be effective in the online learning environment. This is pivotal in a leadership course that calls for a high degree of self-reflection. Moreover, unlike the on-campus classroom setting, the online environment also offers students the opportunity to work in virtual teams. Armed with firsthand knowledge of the potential strengths and limitations of this group process, students will be better prepared for the realities of the modern workplace, where face-to-face meetings are often viewed as luxuries that many multinational and even national organizations can ill afford. Online students are more likely to gain experience with the application of the communicative, technical, and interpersonal skills needed to be effective virtual team members: with less dependence on the instructor and increased learner–learner interaction, these students have the opportunity and obligation not just to read about leadership skills, but also to exercise those skills in the online environment.

Movies as Teaching Tools

Movies have been used as educational tools for many years. The principles of leadership and character development can be brought to life very effectively through the use of films. Movies are a very appealing way to connect the student with course material and enrich the learning experience beyond text-based reading assignments. A well-written and well-acted movie can grip a student's attention and provide an ideal focal point for discussion. Billsberry and Edwards (2008) note an explosion of interest in using cinema to examine management and leadership behavior because film vividly and captivatingly brings leadership to life. They speak of the richness and complexity of the portrayal of leadership that would be difficult to replicate in other mediums. By providing a common experience that extends beyond the textbook readings and cases, films are likely to motivate and spark the interest of students while providing an excellent avenue for interaction among them. Miller (2009) contends that media such as movies can markedly augment learning content by way of generating vivid and complex mental imagery. He asserts that movies help students acquire the mental imagery essential for conceptual understanding by stimulating learning at both the cognitive and affective (emotional) levels. This is especially crucial for an online course on leadership that deals with complex behavior. In such a course, seeing is believing: when concepts are seen enacted on the screen and manifested in the context of an unfolding narrative, they will likely become much more meaningful to students.

Movies can also enhance learner comprehension by employing blends or mixes of sights and sounds that appeal to variable learning styles and preferences (Miller, 2009). Within the leadership domain, movies can present a real-time, multidimensional portrayal of leadership, and show how complex and challenging leadership is or can be by depicting the leader succeeding as well as stumbling. Miller suggests the most important function in terms of cognitive learning is for the film to supply representational applications for key course ideas. This is a crucial factor in a course on leadership. In particular, the right movies (such as Twelve O'Clock High, which will be discussed in more detail later in this paper) can bring to life theories such as Kouzes and Posner's (2007) five practices of exemplary leadership, Fiedler's (1967) Contingency Theory of Leadership, and Blake and Mouton's (1964) Leadership Grid, among others.

Logistics of Learner–Learner Interaction

The development of community must be a deliberate and intentional goal, and the achievement of that goal needs to be built soundly into the design of an online course (Vesely, Bloom, & Sherlock, 2007). Taormino (2012) laments that there are many examples of low-quality online experiences in which students read articles and watch videos on their own, and complete assignments with little interaction. Building interactivity into online courses ensures they are more than glorified correspondence courses. For example, online discussion boards, a standard feature found in course management systems (CMSs) like Blackboard, can be used to enable asynchronous communication among course participants. Because instructors are often dealing with students in multiple time zones, it can be impractical or impossible to hold synchronous (live) discussions. A discussion board allows the instructor to post questions, a case, or an assignment that students can discuss at their convenience up until the due date.

In order to make discussion boards work, it is imperative that students are graded on both the quality and quantity of their participation, and those grades must include responding to the postings of other students. Generally speaking, students should respond to at least three to four postings by their classmates, and those postings must be substantive – not just "I agree." Frequently, students are required to provide sources and citations for their responses. From the authors' own experience, discussion boards seem to work most effectively if two due dates are provided: for example, a discussion-board activity might run from Monday morning until Sunday night (one week), with initial postings by each student (based on the questions posed by the instructor) due by Thursday and responses to fellow students due by Sunday. This prevents everyone from waiting until the last minute to post, which would have the effect of stifling the ongoing discussion. The instructor can choose to either engage in the discussion with the students, or alternatively, wait until the conclusion of the discussion to add his/her perspective on the questions at hand.

It is important to continue to monitor the discussion to ensure that students stay on topic and that the discourse remains civil. Many students have strong opinions and tend to prefer to express their own views rather than reinforcing what others have said on the discussion board. Nevertheless, it is important to stress that students' contributions should represent their own views. Grades for weekly discussions can be posted to the Gradebook or similar feature within the CMS at the end of the discussion so that students are able to retrieve them in a timely fashion. Smith, Ferguson, and Caris (2002) contend that class participation should make up a higher percentage of the grade in online courses, since such participation can be more objectively assessed in terms of both quantity and quality.

Online Groupwork

Managing and working in virtual teams can be a daunting and challenging process, but such teams are a reality in today's global workplace and economy. Introducing students to the process early on can be beneficial to them in many ways. Blackboard has a built-in Groups function that allows for instructors to place students into groups, or for students to form their own teams; it is up to the instructor to determine which approach to use. If the instructor forms the teams, it can be helpful to do so by time zone. Another option is to have students post "help wanted" advertisements on the "Student Lounge" discussion board to recruit students with similar work habits and/or interests to be part of a team. These self-formed teams can be more effective and may yield a better experience for students. The Groups function allows the instructor to set up discussion boards for within-group communication. The instructor can monitor those boards to see how the group is progressing, and if he/she sees a lack of activity or potential problems arising, he/she can intervene. The Groups function also includes a file-exchange mechanism for students to easily send work to one another, and it provides access to group members' e-mail addresses.

It is a good idea for students to set up "rules of engagement" for their teams to lay out expectations of how quickly e-mails and telephone calls will be returned, establish deadlines for assignments, and delineate each team member's role for the assignment. Instructors can supply guidelines on these rules of engagement, for example in the form of a sample contract that students can adapt and use for their teams. Students should be encouraged to develop their own rules and procedures to supplement the standard contract; graduate students are generally allowed more freedom to develop their own processes, while undergraduate students are given more guidance. All team members are asked to sign a copy of the rules/contract, which is then sent to the instructor. Should problems arise in the group, students can be referred back to the signed contract as a first step in resolving any differences. In terms of group size, the authors have found that small groups of three to four members work best. Vesely et al. (2007) also recommend small groups as these allow for greater and richer interaction among members.

Keebler's (2009) position is that an effective online teaching strategy involves specific discussion questions to initiate and spur dialogue among learners. Vesely et al. (2007) posit that the development of an online community is encouraged with the use of structured collaborative activities in course design. The inclusion of opportunities for ongoing interaction among class members is critical. In online learning, it is essential that very clear and unambiguous instructions are given for each assignment. For lengthier assignments the instructor should consider multiple, interim deliverables and due dates so that portions of the assignment can be evaluated along the way to ensure students are on the right track. Well-defined questions, ongoing feedback, exemplars of similar assignments, and being available to answer questions are all keys to success.

Smith et al. (2002) counter the arguments of those who believe the online learning environment lacks the energy of live classroom dialogue by maintaining that in a face-to-face setting only a few students actually engage in the dialogue, due to time constraints. They argue that in fact, most students remain anonymous in the face-to-face classroom environment. Smith et al. point out that in an online discussion, every student must participate, and this increased frequency of engagement can lead to more productive learning. In particular, they suggest asynchronous dialogue provides the students with a broader and deeper understanding than is able to be achieved a traditional classroom. Students can read a posting and consider their response before replying to the threaded discussion; this act of consideration and the emphasis on the written word encourages a deeper level of thinking (Smith et al., 2002). Keebler (2009) also refers to this type of dialogue as allowing greater reflection and a more in-depth understanding.

Using Movies in Online Courses

Movies can be used in online courses in a number of different ways. A short clip or excerpt can be provided through the CMS, and it may form the basis for a weekly discussion-board activity. However, it is important in this case to keep copyright laws in mind. In the United States, for example, only short, discrete portions of a film can be used in this manner, in accordance with copyright/fair use regulations. (Please see University of Minnesota Libraries, 2010 for a more detailed discussion of the application of American copyright law to educational materials.) Alternatively, students could be required to watch an entire movie (the authors' preferred way) and complete either an individual or team assignment (the latter is preferred by the authors) based on that movie. These are the same activities that would be completed in class, but adapted for online delivery. Students are required to obtain a copy of the film (through purchase or rental) and watch it offline.

Because of the geographically dispersed arrangement of the students in most online classes, it is likely that the majority of discussions will be asynchronous rather than synchronous. Nevertheless, this generates scope for more in-depth discussions. Students can be expected to integrate more research into their responses to questions that instructors pose – something instructors would not be able to do as easily in a face-to-face classroom situation. Miller (2009) highlights the ease with which media can be obtained today in comparison to past decades. For example, commercial movies have become increasingly available on the Internet, with legitimate websites (e.g., Netflix, Vudu) offering significant inventories of free or low-cost streamed films. Thus, logistically, it is not difficult for most students to watch a required movie. This said, it is important that the instructor stresses the importance of obtaining the film from a legal and reputable source. It is also advisable to warn students beforehand if the film contains explicit language and/or sensitive subject matter, by posting an advisory online. As in the face-to-face classroom, the instructor can choose to provide a single grade for the entire team, or may use a combination of group and individual grades. If the latter is chosen (the authors' preferred method), then each team member indicates which portion of work he/she contributed, and is evaluated both on his/her individual contribution and on the overall quality of the team's finished assignment. One essential element of online teaming is peer feedback, so a portion of the grade on the assignment should be derived from this. This helps to combat "free riders" and encourages team members to put in their fair share of work.

Twelve O'Clock High (Zanuck & King, 1949) is used here as an example of a film applied to leadership theory in an online course. In particular, the authors use this movie as an educational tool for demonstrating transformational leadership in their online courses. There are many outstanding movie portrayals of leadership that they have used in their leadership classes over the years. The movie Twelve O'Clock High has long been recognized as a classic leadership movie, one of the best that showcases leadership theories (see Graham, Sincoff, Baker, & Ackermann, 2003 for a list of leadership movies). Bognar (1998), for example, refers to this movie as a "superb treatise on understanding the charismatic leadership paradigm" (p. 94) from which he draws numerous leadership lessons applied to the military.

Twelve O'Clock High stands out as a movie that is "pure leadership" without any extraneous material or distracting subplots. It is based on a book about the actual experiences of World War II (WWII) pilots, and a romantic subplot was purposely left out of the movie. Every scene in the movie deals with leadership, whereas in many movies there are several storylines, with only one actually dealing with leadership. Moreover, Twelve O'Clock High is one of the few movies that addresses several hierarchical levels of leadership: it speaks to both the strategic and interpersonal levels, or both the macro and micro levels, of leadership. Most other films only handle the micro or interpersonal level, such as the leader's relationship with the group. For instance, the portrayal of leadership in the movie Apollo 13 (Grazer & Howard, 1995) is very much a micro-level portrayal. Twelve O'Clock High depicts strategy implementation across several levels, from top command to actual implementation by the lowest level in the hierarchy.

The film continues to be used by the U.S. military in leadership-development training for both officers and enlisted personnel. With the wide variety of movies available that demonstrate leadership within a military setting, Twelve O'Clock High continues to be viewed as a film that clearly illustrates the essential role of effective leadership in ensuring successful organizational performance. This movie shows transformational leadership at work as it chronicles the growth of a dysfunctional military unit under a new leader. To briefly summarize, this WWII film is set in 1942 England and deals with the U.S. attempt to prove the superiority of daylight-precision bombing over the British night-time bombing. Specifically, it tells the story of the 918th Bomber Squadron. There is a high sick-leave rate in this dysfunctional squadron, with the incumbent leader, Keith Davenport, beaten down and blaming bad luck for their problems. Davenport's leadership is based solely on his relationship with his men, and he prioritizes this relationship over getting the job done. Much of leadership is the management of culture and meaning (Schein, 1985) and judging one's subordinates, because strategy is ultimately implemented by people. The decision is made to replace Davenport with Frank Savage, who is brought in to turn things around.

Savage, the main character, is a textbook case of effective transformational leadership until he falls apart due to a conflict of personal versus organizational decision issues at the end of the movie. This film also shows students that leaders bear significant responsibility, and that their decisions have far-reaching impact and consequences. Savage is in a hurry; he is eager to raise the group's performance as quickly as possible. He reveals his vision to put pride back into the group, so that the worst thing conceivable would be for a man to be left behind on a mission. Savage paints a picture of meaning and importance of the squadron and its bombing attacks on the enemy. As the squadron members buy into his vision, he is able to transform the formerly dysfunctional group so that everyone wants to fly. In fact, ground personnel are actually sneaking aboard the planes so that they can be a part of the big mission!

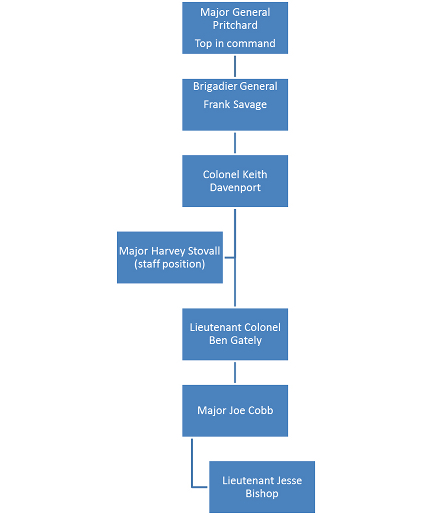

When using movies in online courses, the students can be provided with a character list or chart for the movie, along with a set of questions that require them to work with one another in a group project. The authors' students are asked to analyze the Twelve O'Clock High film using leadership material from the course. For example, they are required to apply transformational leadership using Kouzes and Posner's (2007) five practices of exemplary leadership from their book The Leadership Challenge. The five practices are "model the way," "inspire a shared vision," "challenge the process," "enable others to act," and "encourage the heart"; there are numerous examples of each of these practices in the film. To illustrate, in terms of "challeng[ing] the process," the leader experiments and takes risks by generating small wins; an example of this from the film is when Savage ignores the radio recall order for all air squadrons to turn back during a critical air-strike mission. He directly disobeys the recall order in order to give his team the chance to succeed in hitting the target where no other squadron was able. See Table 1 for a list of the characters and Figure 1 for a command structure. Table 2 contains a list of broad and specific questions that the authors use for their leadership films.

Table 1. List of major characters in Twelve O'Clock High

Character |

Actor |

Major General Ben Pritchard |

Millard Mitchell |

Brigadier General Frank Savage |

Gregory Peck |

Colonel Keith Davenport |

Gary Merrill |

Lieutenant Colonel Ben Gately |

Hugh Marlowe |

Major Harvey Stovall (administrator; staff position) |

Dean Jagger |

Major Kaiser (doctor; staff position) |

Paul Stewart |

Major Joe Cobb |

John Kellogg |

Sergeant McIllenny (Savage's driver) |

Robert Arthur |

2nd Lieutenant Jesse Bishop |

Robert Patten |

Figure 1.Chain of command in Twelve O'Clock High

Table 2. List of movie-related questions

General/broad questions |

Assignment: Analyze the film as a leadership case. Apply the text and readings to the movie and any characters who you feel played significant leadership roles. What did the main character and others do well (or not) according to course material? Why did it work (or not)? What could the main character and others have done to improve? What mistakes did he/she or others make? Could any one of them have been more effective? Why did the main character (and others) each behave as they did (motivation)? The preceding involves accounting for the main character's and other persons' successes or lack thereof and exploring their approach to leadership. What leadership lessons did you learn from this project? |

Specific application |

You need to demonstrate that you understand the material we have covered in the course as well as how it applies to leadership issues in the movie (at a minimum, apply Kouzes and Posner's (2007) five practices of exemplary leadership and find several examples of each of the practices), the motivation material, and the self-concept (actual and ideal) for the main character. |

Learning rationale |

It is one thing to read about effective and ineffective leadership. A film allows you to see leadership in action in real time and gives you the chance to see if you can recognize effective or ineffective leadership practices, and to apply course material. A group project provides an opportunity for personally exploring leadership issues. Also pay attention to what happens in your group in terms of leadership during the course of this project. |

Leadership Movie Genres

Various genres of potential leadership movies exist. Military leadership is demonstrated in The Bridge on the River Kwai (Spiegel & Lean, 1957); teachers exhibit leadership qualities in To Sir, with Love (Clavell, 1967); sports figures embody the spirit of leadership in Remember the Titans (Bruckheimer, Oman, & Yakin, 2000); and leaders take on injustice in the legal realm in Erin Brockovich (Shamberg, Sher, DeVito, & Soderbergh, 2000). (See Table 3 for other movie suggestions.) The authors beg to differ with Billsberry's (2009) contention that there is an almost limitless list of possible films for use in leadership courses; in their view, many of the best leadership movies are based on true stories. Fictional movies, especially some notable recent ones, tend to have negative stereotypes of the actual leaders, with the movie's hero being portrayed as an anti-establishment character fighting against the "evil" leaders in society (e.g., Avatar – Landau & Cameron, 2009). Part of the appeal of the based-on-a-true-story movies is their realistic portrayal of the leader as a person, warts and all. To qualify as a potential film to be used in a leadership class, a movie should contain a believable leader, sometimes winning and sometimes failing, rather than an invincible cartoon-like character.

Table 3. List of leadership movie genres, with examples

Military |

Bridge on the River Kwai; Twelve O'Clock High; Master and Commander; Braveheart |

Teachers as leaders |

To Sir, with Love; Freedom Writers; Lean on Me; Stand and Deliver;

Dead Poets' Society |

Sports |

Coach Carter; Remember the Titans; Invictus |

Fighting injustice |

Patch Adams (medical); One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest (mental health);

Erin Brockovich (legal); Norma Rae (labor); To Kill a Mockingbird (racism) |

Bio-pic |

Gandhi; Patton; Warm Springs (Franklin D. Roosevelt); The Queen; Elizabeth |

Conclusion

One clear finding from the Vesely et al. (2007) study is that it is incumbent upon faculty to play a leadership role in building community in their virtual classrooms. Students indicate that instructor modeling is the most important element in building this online community. The heavy requirements for participation in online courses can often result in stronger relationships (both instructor–student and student–student) being formed than in face-to-face classes (Smith et al., 2002). The relationship between instructor and students is particularly important in a leadership course, where the instructor can model leadership behavior to the class. As online learning matures and solidifies itself as a viable ongoing venue to deliver education to students at all levels, it challenges instructors to continue to build an effective, meaningful learning environment. As technology becomes more sophisticated and students demand more multimedia learning tools, instructors must respond with techniques to engage online learners.

Movies have been effectively implemented in face-to-face classrooms for years. There is no reason to believe that they cannot also be effectively applied in an online course. In fact, given the vivid imagery of film coupled with the required interaction and reflection, movies can be particularly effective in online courses. Movies can be seen as more than entertainment by setting the scene for analysis and application of theory and course material. They engage the interest of students and provide an excellent way to build learner–learner interactivity into a course. Movies are particularly useful in leadership education as they can provide role models of both effective and ineffective leadership practices that students can identify and discuss. As noted earlier, not only can movies help students understand course concepts, they can stimulate learning at both cognitive and emotional levels, which is especially important in a leadership course dealing with the complexities of human behavior (Miller, 2009). In particular, Twelve O'Clock High is recommended as an excellent teaching tool that instructors can adapt to online leadership courses. It is rich with examples of leadership challenges and setbacks that are sure to engage the viewers and generate lively and energetic online discussions.

Online courses have been criticized for their lack of face-to-face interaction or real-time dialogue among students. This position paper has argued that utilizing movies can be an effective way to generate interactivity and reflection in online leadership courses, and ultimately deliver a learning experience that is equal to or surpasses that offered in the traditional classroom. In particular, the paper has demonstrated the logistics of film as a teaching tool to build learner–learner interactions using a strong leadership movie such as Twelve O'Clock High.

References

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2010). Class differences: Online education in the United States, 2010. Babson Park, MA: Babson Survey Research Group. Retrieved from http://www.sloanconsortium.org/sites/default/files/class_differences.pdf

Billsberry, J. (2009). The social construction of leadership education. Journal of Leadership Education, 8(2), 1-8. http://www.leadershipeducators.org/Resources/Documents/jole/2009_fall/Billsberry.pdf

Billsberry, J., & Edwards, G. (2008). Toxic celluloid: Representations of bad leadership on film and implications for leadership development. Organisations & People, 15(3), 104-110.

Blake, R., & Mouton, J. (1964). The Managerial Grid: The key to leadership excellence. Houston, TX: Gulf.

Bognar, A. J. (1998). Tales from Twelve O'Clock High: Leadership lessons for the 21st century. Military Review, 78(1), 94-102.

Bruckheimer, J. (Producer), Oman, C. (Producer), & Yakin, B. (Director). (2000). Remember the Titans [Motion picture]. USA: Walt Disney Pictures.

Clavell, J. (Producer/Director). (1967). To Sir, with love [Motion picture]. UK: Columbia Pictures.

Du, J., Durrington, V. A., & Mathews, J. G. (2007). Online collaborative discussion: Myth or valuable learning tool? MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 3(2), 94-104. Retrieved from https://jolt.merlot.org/vol3no2/du.htm

Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Graham, T. S., Sincoff, M. Z., Baker, B., & Ackermann, J. C. (2003). Reel leadership: Hollywood takes the leadership challenge. Journal of Leadership Education, 2(2), 37-45. Retrieved from http://www.leadershipeducators.org/Resources/Documents/jole/2003_winter/JOLE_2_2_Graham_Sincoff_Baker.pdf

Grazer, B. (Producer), & Howard, R. (Director). (1995). Apollo 13 [Motion picture]. USA: Universal Pictures.

Johnson, E. S. (2007). Promoting learner–learner interactions through ecological assessments of the online environment. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 3(2), 142-154. Retrieved from https://jolt.merlot.org/vol3no2/johnson.htm

Keebler, D. W. (2009). Online teaching strategy: A position paper. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 5(3), 546-549. Retrieved from https://jolt.merlot.org/vol5no3/keebler_0909.htm

King, A. (1993). From sage on the stage to guide on the side. College Teaching, 41(1), 30-35. doi:10.1080/87567555.1993.9926781

Kouzes, J., & Posner, B. (2007). The leadership challenge (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Landau, J. (Producer), & Cameron, J. (Producer/Director). (2009). Avatar [Motion picture]. USA: Twentieth Century Fox.

Miller, M. V. (2009). Integrating online multimedia into college course and classroom: With application to the social sciences. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 5(2), 395-423. Retrieved from https://jolt.merlot.org/vol5no2/miller_0609.htm

Nagel, D. (2009, October 28). Most college students to take classes online by 2014. Campus Technology. Retrieved from http://www.campustechnology.com/articles/2009/10/28/most-college-students-to-take-classes-online-by-2014.aspx?sc_lang=en

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2001). Lessons from the cyberspace classroom. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning. Madison, WI: The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. Retrieved from http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/Resource_library/proceedings/01_20.pdf

Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Shamberg, M. (Producer), Sher, S. (Producer), DeVito, D. (Producer), & Soderbergh, S. (Director). (2000). Erin Brockovich [Motion picture]. USA: Jersey Films.

Smith, G. G., Ferguson, D., & Caris, M. (2002). Teaching over the Web versus in the classroom: Differences in the instructor experience. International Journal of instructional Media, 29(1), 61-67.

Spiegel, S. (Producer), & Lean, D. (Director). (1957). The Bridge on the River Kwai [Motion picture]. USA: Columbia Pictures.

Taormino, M. (2012, April 25). Re: A "sage on the stage"? A "guide on the side"? What is the role of a teacher online?" [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://www.wiredatheart.com/2012/04/25/a-sage-on-the-stage-a-guide-on-the-side-what-is-the-role-of-a-teacher-online/

University of Minnesota Libraries. (2010). Understanding fair use. Retrieved from https://www.lib.umn.edu/copyright/fairuse

Vesely, P., Bloom, P., & Sherlock, J. (2007). Key elements of building online community: Comparing faculty and student perceptions. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 3(3), 234-246. Retrieved from https://jolt.merlot.org/vol3no3/vesely.htm

Zanuck, D. F. (Producer), & King, H. (Director). (1949). Twelve o'clock high [Motion picture]. USA: Twentieth Century Fox.