|

Introduction

The

Enduring Legacies Reservation-Based Project

(funded by

the Lumina Foundation for Education,

College Spark Washington, and others), now in

its third year, supports Native American college

students of a number of Pacific Northwest tribes.

Educational technologies and e-learning play a

central role in the program. This project involves

three main endeavors.

1)

Associate of Arts.

The first involves the creation of a three-year

associate of arts degree that is fully transferable

to any university in the US. This program combines

e-learning courses offered through

WashingtonOnline (WAOL), a consortium of 34

community colleges of Washington State, with some

credits of face-to-face courses that focus on

humanities credits and topics such as public speech,

writing and literature, e-portfolios, and

battlegrounds (original

Native American teaching case studies learning)

in order to promote the learner cohort and

community. Also, the students meet with a study

leader from their own tribes one day a week to focus

on their studies. Tribal-based study leaders serve

as “whipmen” and work with learners “for tutoring

and mentoring”. The study leader relates to the

learners culturally, and, as a member of the

respective tribe, connects to the social support and

familial structure surrounding each learner.

Historically, Native American societies unite around

caring for their young and students “were not

allowed to fail” (Demmert, Dec. 2001, “Improving…”

p. 1).

The selected courses from the curricular offerings

of WAOL were initially revised in the first year of

the project for more Native American cultural

infusion in the curriculum, and the online faculty

underwent culturally-sensitive instructor training

and intercultural competence at

The Evergreen State College (TESC) campus, with

considerable peer learning from other faculty,

tribal members, and tribal learners. The online

instructors were handpicked for their high

engagement with learners and academic rigor. Events

at The Evergreen State College’s

Longhouse Education and Cultural Center were

designed to help learners meet and greet instructors

- over traditional and friendly forms of the

breaking of bread: fall orientation events like

clam bakes and salmon roasts. This curriculum

related to the

Reservation-Based/Community Determined Bridge

Program’s basic tenets of promoting student’s

personal authority, honoring of indigenous

knowledge, and the use of academics to “complement

personal authority and community knowledge.” Annual

themes of the 2006 – 2009 academic program include

“Contemporary Indian Communities in a Global

Society,” “Traditional Knowledge: The Foundation

for Sustainable Tribal Nations,” and “Integrating

Change in a Communal Society.”

One-credit humanities courses are taught four

Saturday afternoons per quarter at the TESC

Longhouse. These provide opportunities for peer

mentoring and socialization with Grays Harbor

College students in their freshman and sophomore

years mingling with juniors and seniors from The

Evergreen State College. The design of this degree

allows for easier transfer of freshman and sophomore

credits to the university. The pacing - a two year

degree offered over three years - acknowledges the

many outside-of-academia commitments of the Native

American learners and makes the work load more

realistic.

2) High-tech, high-touch hybrid approach.

A second feature employs a “high-tech high-touch”

hybrid approach. The high-tech involves the

Blackboard™ learning management system (LMS),

campus-based student-owned

e-portfolios (with a

learning framework), The Evergreen State College

(TESC) website, and digital learning artifacts. The

use of e-learning technologies allows a much deeper

reach into the geographically dispersed and somewhat

isolated

reservation-based tribes of the Pacific

Northwest for “place-bound” learners. The benefits

of the LMS are manifold. The courses used and

developed are digitally archived and may be

transferable to others. Any revisions to the

courses may benefit more than the targeted Native

American because of copyright releases built into

all system-owned courses in WashingtonOnline. The

use of accessible builds - through authoring tools

and an accessible LMS - make the curriculum

applicable to a wider audience.

The use of the World Wide Web (WWW) to collect and

deploy various learning resources in e-portfolios

and case studies magnifies the influence of this

program beyond the boundaries of the various

educational institutions. The ability to publish

broadly affords the Native American students (and

studies) voice, reach and often, respect.

The use of these technologies also involves some

cultural border crossing in the sense that many

Native American communities have been “have-nots” in

the “digital divide.” This program gives

software-loaded laptop computers to the learners as

part of the learning, and it includes face-to-face

training on the use of BlackBoard™, the laptop, and

Web resources. Native American teaching case

studies may be deployed online for a wider reach for

the curriculum, and many of these cases involve

full-sensory digital wraps (sight, sound, and

hearing). The benefits of the Web for rich research

also strengthen the learning with the definition of

web quests and other online assignments.

3) Native American case studies.

The third strand involves the development of

original Native American teaching case studies

involving primary and secondary research by college

instructors at WAOL, TESC, and experts in the Native

American communities. Teaching case studies support

the value of indigenous knowledge and the learners’

personal observations of the world and their

connections to vibrant communities. These cases

engage issues of relevance to Native American

learners and capitalize on tribal knowledge and

often less-publicly-accessible primary resources.

These may counter the observed Native American

invisibility in both the academic research and the

college teaching (Demmert, Dec. 1001, “Improving…A

Review of the Research Literature,” pp. 3 – 4).

These teaching cases are available on the WWW

and are shared with Creative Commonsk-type global

publication.

Participants. The

Evergreen State College (TESC) serves as the lead

institution in this collaborative endeavor.

Grays Harbor College (GHC) is the supporting

college, and WashingtonOnline (WAOL) serves as the

main online course provider. The Enduring Legacies

Reservation-Based Project started in Sept. 2005 with

an initial half-dozen First Nations tribes: the

Makah, Muckleshoot, Nisqually, the Port Gamble

S’Klallams, Quinault and Skokomish. By the second

year, a number of others had joined: Squaxin, Lower

Elwha Klallam, Quileute, and Shoalwater Bay. By Jan.

2007, the Chehalis Tribe had joined.

This paper addresses one aspect of this project:

the pedagogical and e-learning strategies applied to

the culturally sensitive curricular redesigns for

English Composition 1 and 2 (which involve essay

writing and research respectively). These are

foundational and required courses for a number of

degree programs and certificates, and the subtle

curricular redesigns for both courses address issues

of cultural sensitivity and learner focus.

Paper Organization

The paper will begin with a brief pedagogical

rationale for the cultural sensitivities approach,

with a focus on Native American learners’ cultural

needs. Then, some course redesign strategies used

by the WAOL instructors will be summarized. The

paper then focuses on the culturally targeted online

course redesign work cycle before addressing the

specifics of the two English courses in the

redesign.

Brief Pedagogical Rationale

Culture in learning has been discussed in the

research literature in different ways - as different

expectations, worldviews, assumptions, emotions and

comfort zones. It is part of the social landscape

that people are habituated to and often becomes

invisible until it conflicts with others’

expectations. Culture may be learned and unlearned.

Adaptive and variable, culture evolves (Nee and

Wong, 1985, p. 287, as cited by Aldrich and

Waldinger, 1990, p. 125).

Culturally sensitive approaches to learning came

into focus in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a

response to the growing diversity in US classrooms

and “concern over the lack of success of many

ethnic/racial minority students despite years of

education reform” (Pewewardy and Hammer, Dec.

2003). Here, a culturally relevant instructor may

mitigate some of the “social-historical-political

realities beyond the school” that may constrain

learning (Osbourne, Sept. 1996, p. 291).

Ladson-Billings’ theory of culturally relevant

pedagogy suggests dynamic “culturally responsive”

actions by instructors, regardless of their own

cultural backgrounds. There must be a focus on three

realms: conceptions of self and others, social

relations, and conceptions of knowledge (Autumn

1995, pp. 478 – 481). Ladson-Billings, in a

prescient work, suggests that culturally attuned

instructors must see themselves as part of the

community and believe that the students are capable

of academic success; they must see their pedagogy as

“art—unpredictable, always in the process of

becoming” (Autumn 1995, pp. 478 – 479). They must

maintain fluid student-teacher relationships;

demonstrate a connectedness with all of the

students, and develop a community of learners, among

which students learn collaboratively and responsibly

(Autumn 1995, p. 480). Culturally responsive

instructors also need to view knowledge as “shared,

recycled, and constructed,” and they must build

bridges or scaffolding to facilitate learning; they

must use a range of multi-faceted assessments for

multiple forms of excellence (Autumn, 1995, p.

481).

Adhering just to mainstream norms in education may

be exclusivist and socially myopic. Pewewardy and

Hammer observe: “Ultimately, the attitudes,

beliefs, and actions of the school must model

respect for cultural diversity, celebrate the

contributions of diverse groups, and foster

understanding and acceptance of racial and ethnic

plurality” (Dec. 2003).

The grounds for a culturally sensitive course

redesign lie in a deep knowledge of and empathy with

the Native American learners and their respective

cultures. Instructor sensitivity to the unique needs

and personalities of each learner will be critical

and possibly even more relevant than generalizations

about their cultures. In this case, cultural subject

matter experts (SMEs) with ties to TESC were brought

in to advise and to critique the course redesign

plans and actual course rebuilds.

Online means have been used to teach issues of

intercultural competence, respect for others’ ways

of life, changing perspectives, and the promotion of

knowledge about one’s own and others’ cultures (Liaw,

Sept. 2006, pp. 49 – 64). Online learning

technologies have been used for adaptive cultural

heritage learning (Casalino, D’Atri, Garro, Rullo,

Sacca, and Ursino, n.d.,

p. 224-).

Culture may affect learning preferences and styles.

Culture may affect perceptions of “time, gender,

dress, source of authority, individualism,

risk-taking, life goals, relationship of education

to community goals, and previous classroom

experience” on learning styles (Boiarsky, 2005, p.

48). A Native American journalist sees the Internet

as “raising the volume” as a “continuing legacy of

storytelling” and a sign of genetic memory for

storytelling (Merina, Fall 2005, pp. 32 - 33).

As many peoples, Native American comprise less than

1.5% of the US population. Half live in urban areas,

and fewer than 33% on reservations. Some 550 tribes

are federally recognized. As a group, only 15% of

Native American students who went on to college

achieved a four year degree, with an overall average

college graduation rate of 3%, compared to 16% for

the general population (Tierney, 1991; Fries,

1987). Kroc, et al.

(1995, p.2) found underrepresented Native American

learners with graduation rates at 17

percentage points lower than for the white student

rate. Of the American Indian students entering

university in the mid-1990s, only 24% had completed

a pre-college curriculum compared with 56% of all

college-bound graduates” (Pavel et al, 1998, as

cited by Kirkness and Barnhardt, 2001, p. 3). The

U.S. Secretary of Education’s Indian Nations at Risk

Task Force (1990 and 1991) found that “schools that

respect and support a student’s language and culture

are significantly more successful in educating those

students” (Reyhner, 2002 / 2004).

Washington State has one of the main regional

concentrations of Native Americans. Two-thirds of

Native Americans are found in ten states, including

Washington (Shumway and Jackson, Apr. 1995, p.

191). This state’s higher education statistics echo

the national crisis in Native education. There are

158,940 American Indians and Alaska Natives living

in Washington State, according to the U.S. Census.

In this state, the large majority of Indian children

are failing in all subjects at all grade levels on

Washington Assessments of Student Learning tests.

At least 32% of Washington Native American students

do not complete high school (Office of

Superintendent of Public Instruction, Washington

State). Thirty-six percent of Indian students

receive a B.A. within six years of entering a

four-year college program. Fifteen percent of

degree-seeking Indian students in Washington receive

a community college degree within 3 years—and the

large majority of Indian students attend community

colleges (National Center for Ed Statistics;

Washington Higher Education Coordinating Board).

Nationally, only 29% of the Indian population is a

high school graduate, compared to 79% of whites.

Solutions to the challenge of educating a larger

number of Native American learners require

partnerships, especially in Washington where half

the students begin college in a two-year

institution, and the transfer and baccalaureate

completion rates are low (“Proposal to the Lumina

Foundation for Education”, Aug. 18, 2006, p. 3).

In using G. Hofstede’s

cultural dimensions model, Native American

cultures—while diverse—may be described through the

issues of power distance, individualism,

masculinity, uncertainty avoidance and long-term

orientation quite differently than mainstream

American culture (“Geert Hofstede™ Cultural

Dimensions”, 2008). “Power distance refers to the

unequal distribution of power, prestige and wealth

in a culture. Individualism looks at the

degree of cultural emphasis on the individual vs.

the collective. Masculinity examines the cultural

focus on traditionally masculine vs. feminine

traits. Uncertainty avoidance looks at the value

placed on risk and ambiguity. Long-term orientation

examines the focus on short-term vs. long-term

forward-thinking values in a particular culture” (Hai-Jew,

2007, p. 8). Native cultures tend to be less

tolerant of high power difference differentials;

they tend to focus on the collective instead of the

individual; they focus on more traditionally

feminine values; they are comfortable with

ambiguity, and they tend to maintain more of a

long-term orientation.

Another way of viewing the cultural divide may be

between Western and Non-Western worldviews. Some

Native Americans may subscribe more to the

Non-Western model, which emphasizes group

cooperation and group achievement, “value harmony

with nature, time is relative, accept affective

expression, (value) extended family, (practice)

holistic thinking, (see) religion permeating

culture, accept world views of other cultures, (and)

(be) socially oriented” (Sanchez and Gunawardena,

1998, p. 51). A subjective and relativist approach

to reality may be more common: “Objectivist

research has contributed a dimension of insight, but

it has substantial limitations in the

multidimensional, holistic, and relational reality

of the education of Indian people. It is the

affective elements - the subjective experience and

observations, the communal relationships, the

artistic and mythical dimensions, the ritual and

ceremony, the sacred ecology, the psychological and

spiritual orientations - that have characterized and

formed Indigenous education since time immemorial” (Cajete,

1994, p. 20).

Academic competition between learners is

discouraged, contrary to many of the confrontational

student-competitive approaches. Culturally, Native

Americans revere Native art and share a mythical

storytelling. Native American students may mask

their competence so as not to stand out from others

in their communities (Swisher, 1991). Those who do

earn their higher education degrees may have a

reverse acculturation challenge in reintegrating

with their communities.

E.T. Hall’s high- and low-context cultures analysis

could be understood as also applying to this

cross-cultural situation. High context cultures

understand information to be an inherent part of a

person, so a minimal amount of verbal interchange is

needed in human relationships. Because they have

experienced stable traditions and history, “age,

education, family background and such things that

confer status do not change rapidly. In dealing

across cultures, high-context cultures become

impatient and irritated when low-context people

insist on giving them information they do not need.

They perceive low-context people as being less

credible because silence sends a better message.

High-context cultures tend to handle conflict in a

more discrete and subtle manner and are predisposed

to require learning for the sake of learning. For

example, high-context cultures include … Native-American(s)”

(Sabin and Ahern, 2002, p. S1C-11).

The concept of an “Indian theory of education” was

offered by E. Hampton, a Chickasaw academic from

Oklahoma. He listed the twelve ‘standards’ on which

to judge any such effort for creating education for

Native Americans: spirituality, service, diversity,

culture, tradition, respect, history,

relentlessness, vitality, conflict, place, and

transformation (1998, p. 19, as cited by Kirkness

and Barnhardt, 2001, p. 8).

However, there are

detractors to the idea of cultural learning

dispositions (Brown, 1979; Chrisjohn & Peters, 1989;

Harris, 1985; Shepard, 1982; Stellern, Collins,

Gutierrez, & Patterson, 1986; Bland, 1975; Kleinfeld

and Nelson, 1991; Stellern, Collins, Gutierrez and

Patterson, 1986). Several warned of taking

uncritical approaches to the idea of Native American

cultural dispositions towards learning (Chrisjohn

and Peters, 1989, as cited by Pewewardy, 2002, pp.

22 – 56; McCarty, et al., Mar. 1991, pp. 42 – 59).

Culturally Targeted Online Course Redesigns

Combined with the unique needs of many in Native

American communities, the instructors applied

concepts of a kind of universal design. The concept

is to create barrier-free learning (“Universal

Design,” Nov. 12, 2007), without cultural

hindrances. In the same way that accessibility may

be designed into structures, such broad-spectrum

solutions help everyone, not just those from a

special group. This approach was needed because

these courses for the Native learners would be

taught to mainstream learners simultaneously. Too

much of the cultural tuning may conversely make the

curriculum too difficult for non-Native learners.

Augmented curriculum for cultural awareness.

One political science course on American government

involved a deeper integration of tribal

organizations, treaty rights and intergovernmental

relations to include the Native American view. One

objective was to ensure that students “more

effectively understand the unique relationship

between federal and state authorities and Native

American tribal government.” Textbook readings were

integrated with Web links and video clips for more

rich learning. A Native case study was included in

the learning. A group project was designed to

address Native American cultural property rights.

“Redesigned assignments emphasize relationships

between First Peoples and local and national

governments” (Enduring Legacies Course Redesign

Report, 2007). Here, the instructor strove to

create more cultural relevance for Native learners.

Scaffolding for disadvantaged learners.

Other courses humanized the technology for students

unaccustomed to computer technologies by offering

extra credit assignments to encourage familiarity

and facility with the LMS and virtual learning

environment. Developmental learning add-ons to

mitigate the preparedness of some of the less

prepared learners was designed, such as through the

building of a glossary of terms, incremental

assignments to help students build their larger

projects step-by-step, simplified languages and

terminology were used. One math teacher worked out

a number of solutions for the learners to study,

learn from and master. A biology instructor designed

at-home “web labs” that would allow learners to buy

the materials at local grocery stores and to pair up

with other learners to actuate these experiments,

for lowered cost barriers.

Promoting Native American scholarship.

An anthropology professor used readings from Native

American writer-scholars. She included more work

that took place within the learners’ individual

tribes. Her assignments targeted issues within the

tribal communities (Enduring Legacies Course

Redesign Report, 2007).

Communal learning.

An art instructor integrated more Washington State

Native American art into her course and emphasized

experiential and communal learning by using forums

for student-to-student discussions. She built

studio critiques or “visual evaluations of the

student’s and peer’s work(s)”. She strove to make

the course “more culturally sensitive and relevant

to all the multicultural aspects of contemporary

society”. She encouraged research topics along the

lines of which indigenous people’s works affected

the works of modern artists, to emphasize the

“fusion of materials, formal elements, and

contextual themes that artist deal with on a daily

basis.” She avoided artificial “subjective

hierarchies” sometimes used in the definition of

art. Likewise, a music instructor redesigned his

music course to reflect more Non-Western culture.

He adapted his adopted textbook to Native American

resources and Nonwestern music sites (Enduring

Legacies Course Redesign Report, 2007).

Researching and learning.

The course instructors all researched more about

Native American studies and history. One music

instructor wrote: “Also, I have been actively

exploring, reading, researching American Indian

music…examining its influence on Western Art music”

(Enduring Legacies Course Redesign Report, 2007).

Defined virtual spaces.

A math instructor defined the e-learning paths in

her course more clearly and offered a richer range

of assignments (“Search the internet (sic) for

information about any mathematical topic of your

choice such as how math was used in an early culture

such as a Native American tribe or any other culture

of your choice” (Enduring Legacies Course Redesign

Report, 2007).

Listening to learners.

The instructors also solicited student feedback

(“Student Feedback: What They Say about their

Courses,” 2006). Many designed integrated feedback

loops in their online courses to capture learner

experiences in order to make the courses more

culturally sensitive.

The Courses in the Redesign

English Composition I and II went through this

cultural sensitivity rebuild process. While a

redesign could suggest a thorough change, the

limitations to this project prohibited that. The

Native American cohorts taking these courses would

be only a few students, or a total of maybe less

than a dozen each quarter. That number

would be too small to “carry” an entire course

section. This means that non-Native American

learners would be in the section, and their academic

needs should also be considered. The shared course

model of WAOL meant that these team-created courses

would have to meet the academic requirements of 34

community colleges.

Whatever curricular changes are made should broaden

and promote learning across a wider swath of the

learning public. The changes cannot be so

culture-specific or explicit that it becomes

exclusivist. The “universal design” tenets and

practices would have to be followed. Course

redesigns could not fundamentally affect the

textbook selection, main curricular build,

quarter-length scheduling, main assignments, and

grading structure. In other words, these course

redesigns would have to function implicitly on the

margins—even though they had not been revised

systematically for a number of years.

The course revision build would occur in a master

classroom, isolated from learner access. Once the

build was complete, it would go through an alpha

testing phase with the critique of cultural subject

matter experts (SMEs). Then, after revision, it

would go straight into “beta testing” with student

feedback and insights. Another round of revisions

would follow the first quarter of testing with live

learners.

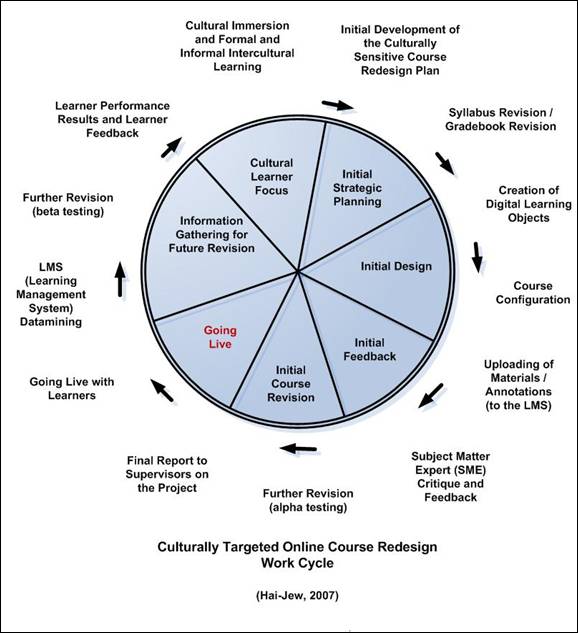

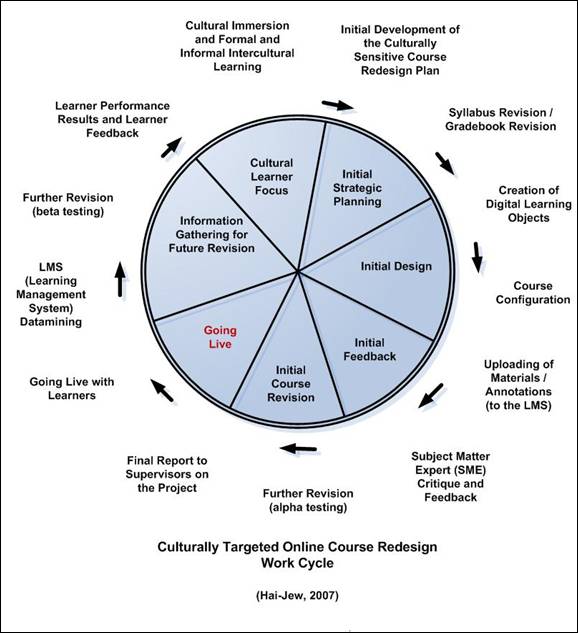

The work progressed in general in the following

way:

-

Cultural Immersion and Formal / Informal

Intercultural Learning

-

Initial Development of Culturally Sensitive Course

Redesign Plan

-

Syllabus Revision, Grade book Revision

-

Creation of Digital Learning Objects

-

Course Configuration

-

Uploading of Materials / Annotations (to the LMS)

-

Subject Matter Expert (SME) Critique and Feedback

-

Further Revision (alpha testing)

-

Final Report to Supervisors on the Project

-

Going Live with Learners

-

LMS (Learning Management System) Data mining

-

Further Revision (beta testing)

-

Learner Performance Results and Learner Feedback (Hai-Jew,

Culturally Targeted Online Course Redesign Work

Cycle, 2007)

Figure 1: The culturally sensitive course redesigns

followed a general work progression.

Defining a Course Revamping

The redesign approaches then are applied to a course

revamping or retrofitting. In broad terms, this

relates to an updating of the pedagogical

approaches. This may involve the application of new

e-learning technologies. New approaches regarding

the design and delivery may add value to the

learning and make it more applicable to learners.

Learning objects may be integrated more tightly with

the defined e-learning paths. A greater range of

ways to move through the curricular materials may be

created. Scaffolding for both amateurs and experts

in the course domain would enhance the accessibility

of the course for a wider range of potential

learners. (Some of these learning experiences will

be mandatory, and others will be opt-in.) Course

resources may be annotated for the other instructors

who may be inheriting the course.

Course revamping should optimally also be informed

by learner feedback about their needs and what would

enhance their achievements. The inclusion of former

learners’ works (with their legal copyright

releases) would help norm quality based on the

reality of what learners are actually producing

instead of a defined normative ideal.

Accessibility retrofitting may involve the inclusion

of verbatim transcriptions for sound files and video

files. Files may be versioned from Word and

slideshow files into portable document files for

easier accessibility. The technological strand is a

part of online learning and should be considered an

integral part of the course revamping.

Some possible re-branding of a course may be

helpful. This would enhance the ecology of the

online learning environment and to make the space

more coherent about the learning and the

professional values of the field.

Some Cultural Assumptions in Relation to English and

Writing

Place-bound learners.

One of the assumptions is that the reservation-based

learners are place-bound. Many not only were single

heads of household with children but also had

full-time jobs (often within their tribes), in

addition to their college studies. This suggests a

requirement for distance access to courses and

on-reservation activities for face-to-face (F2F)

endeavors.

Accessibility. Another angle related to the

place-bound learners is that most learners have

dial-up access because of the lack of broadband

wiring on many reservations. An occasional winter

storm often knocks out electricity access for days

given some of the tenuous infrastructure on some

reservations. Any online course redesigns would

have to take into consideration accessibility and

digital file size and design strategies regarding

video delivery.

Remediation.

For various basic academic skills, many Native

American students need remediation because of the

poor quality of teaching and learning (and often

low-resource conditions) that they received prior to

enrolling in college. This need applies both to

urban and rural learners, non-reservation based as

well as reservation-based. Academic preparedness, of

course, applies to a majority of conventional

university students as well. A curricular build

needs to scaffold for learner preparedness and

academic success as well as to support an internal

locus of control / sense of self-efficacy.

Cultural considerations.

The cultural considerations for these course

redesigns involved a complex mix of understandings

of Native American learners’ living situations,

worldviews, academic needs, understood values

systems, rituals, and motivating topics of interest

(for writing and research). Their communal

orientation came into play in terms of assignment

designs that emphasized cooperative work and support

for community-based writing and research topics.

Technological accessibility.

Many reservation-based learners lack access to

computers in their homes. Many of those who do have

computers have only dial-up Internet access from

their homes. This suggests that the accessibility

design must take into consideration this aspect.

Digital learning objects will need to be updated to

avoid the “slow fires” of disintegration based on

updated software programs (many of which may not be

able to read versions from a few software cycles

back).

Lowering unnecessary costs.

The statistics about Native American learners’

economic lives show many living below poverty. The

costs of college tuition, books and supplies may be

highly prohibitive. Part of these redesigns

involved using electronic book resources and essays

(many from published textbook anthologies) archived

online to save on costs.

Acculturation into academia.

The course rebuilds also involved awareness of the

cross-cultural issues between academia, mainstream

Native American cultures, and online learning

assumptions (Web 2.0, open-source). The awareness of

such challenges led to cross-cultural and

cross-values sharing moderated by the course

annotations, learning activities, and informed

instruction. Surfacing the various cultural

understandings may enhance learner comfort and offer

a language and openness to talk about their own

perceptions and concerns. Defining ontologies in

particular fields may help new learners more quickly

grasp relationships and understandings.

Building for instructor transferability.

Any course that is a shared one (inheritable by

other instructors)

needs to be adaptable. Given that there is little

courseware space for instructor guidebooks, the

learning itself must be common in the stated field,

up-to-date, flexible and pedagogically transparent.

If the value in the learning is not clear from the

beginning, then the course adoption may be more

difficult. Assignments must be able to be

“versioned” for different learning contexts. The

design must be neutral and generally non-political

in order not to be off-putting for various

instructors and their respective learners.

The Teaching / Facilitation of the Online Learning

for Native American Learners

The course redesign did not only refer to the

“static” curricular build elements of the courses

but also in how the courses would be taught.

Connecting people.

The way the redesigned courses would be taught

should align with the cultural sensitivity

concepts. Among some Native American learners, they

talk about “checking heart.” This refers to their

understanding of the motives of others towards them,

in particular those of their instructors. If

benevolence is not found while checking heart,

learners will not take the risks necessary to learn

because they may not feel sufficiently free from

potential harm. This suggests that the instructor’s

telepresence -his or her digital embodiment, voice

and video and still photo depictions, and

interactions in the online classroom - should align

with his or her person. This also would suggest

that learners should be encouraged to bring their

full selves into this online space in terms of their

telepresences as well. They should be welcomed and

supported in a sense of belonging. E-mails sent out

at important junctures to learners (beginning,

midterm and the end-of-term) may encourage stronger

course retention and more participation.

Building community.

Building a sense of community requires the

development of a shared sense of trust and open

communications. Culturally, Native American

learners tend to be drawn to cooperation more than

competition, so shared small group tasks may be more

conducive to some types of learning. Some

Native American learners

also feel awkward having attention directed to them,

so instructors should not create such “calling on”

situations synchronously or asynchronously. The

mainstream American focus on individualism

for topic selection, and the focus on the

first-person point-of-view in essay writing may be

awkward for some Native American learners, so there

should be sensitivity and flexibility about these

issues.

Facilitating group work online requires a range of

skills given the difficulty in coordination,

assignments, guidance, learning support, and

assessment. However, The Enduring Legacies

Reservation-Based Project educators (and

administrators) who work with Native American

students have found that this may be efficacious to

promote their learning online.

A more relativistic sense of time.

The sense of time that many Native American students

share may be less driven or deadline-centered.

Instructors may offer more of a flexible deadline

schema. Instead of daily deadlines, maybe the

closing of forums at week’s end would be helpful.

Extending deadlines based on the unique family,

health and other challenges of the learners may be

more flexible and pro-learning. However, there also

need to be limits to deadline extensions—as these

may be abused to the point where a learner may not

reasonably catch up with his / her peers.

Protection of learner interests.

“Learner interests” may be interpreted in a variety

of ways in freshman composition writing and research

writing courses. Of course, their quality of

learning is important, so they may have transferable

knowledge and skills into their future courses,

careers and lives. Their ability to discover and use

their own voices would be important, which would

suggest their ability to choose writing topics that

are socially, communally (tribally) and personally

relevant (and have learning value). Their

empowerment of speaking out in the larger world also

is critical. Another aspect of learner interests

would be their protection in terms of copyright and

publishing.

Range of assessments.

People with a range of different learning styles may

assess differently based on the assessment

instrument. Being open to different learner

interpretations of the work would be helpful. As

mentioned before, giving learners a wide sampler of

prior student work (with the proper copyright

releases) would be helpful, too. There may be more

connections between learners’ expressed ideas and

formal projects than the occasionally dry writing in

academic texts.

Encouragement of help-seeking behaviors.

Learners’ help-eeking behaviors should be

encouraged for enhancement of their learning.

Research has found that those who have fewer

academic skills tend not to use the resources

provided to them. Building motivations to access

and use such resources are an important part of

curricular rebuilds. “As described earlier, when

students in these studies were provided with helpful

resources (informational and strategic) and given

the freedom to use them, many elected to utilize

little or nothing. As this suggests, learners may

have access to relevant information or strategies

but may not choose to employ them. Because

strategies as we have operationally defined them,

are characterized by carefully planned and

intentional use, their susceptibility to

motivational effects may be rather considerable”

(Alexander and Judy, Winter 1988, p. 396). Lifelong

and discovery learning suggest that learner

help-seeking behaviors would be a critical aspect to

that.

Another assessment approach could be to offer

incremental assignments that coalesce to create the

larger multi-week or term projects. For example,

smaller fine-focused assignments may be designed for

the writing, essay organization, resource evaluation

and citations for the term research paper. This

allows more feedback to learners and support for

their larger projects in incremental ways. This

helps

learners focus on the building of specific skills.

This also may allow more customized and unique

feedback for each learner and more constructive

interactions with the instructor.

Redesigned rewards structure.

With the additional assignments and opt-in

resources, the grading rewards structure was also

redesigned to more fully represent the value in

learner interactivity (higher points) and support of

each other. Extra credit was added to provide

incentives for some of the optional value-added

learning. Learners who published their works in

their respective student or community newspapers

earned extra credit points. This new rewards

structure encouraged deeper learning and also moving

beyond the virtual classroom into the wider world of

publishing and sharing.

A Virtual Community of Online Course Redevelopers

The faculty from various fields working on these

course redesigns did not work in a social vacuum

even though they were separated by distance. WAOL

established an “open house” of courses for mutual

sharing, including the creation of open guest

accounts. A conference was hosted by TESC in the

early summer of 2006 and another in Summer 2007 to

train faculty in the writing of Native American case

studies.

One of the goals of the collaboration was clearly to

support each other’s work. Another was to

collaborate around the goals of interconnectedness

between the learning and transference. For example,

the research and library course was linked to the

various academic projects from the areas of

anthropology, history, and political science. The

premise is that connectivity between the courses

would create a sense of alignment in the course

studies and better transference of reinforced

skills.

The pedagogical theories applied to the course

redesigns should lead to a sense of alignment and

coherence between the

learning objects. A clear learner experience and

e-learning path should exist from the

pre-week through the entire term and into any opt-in

post-week learning. The focus should be both

specific at the learning object level and broad at

the course level.

The Selected Courses

Understanding the original intentions of the initial

lead instructors of both courses and analyzing their

digital artifacts and structural builds may form a

stronger basis for the redesigns. The idea is to

align with the thinking in the respective fields but

also to offer some alternate narratives and

options. Both of these courses were built by lead

instructors with the advisement of colleagues under

course development grants in the late 1990s.

EC1 focuses on a number of learning objectives,

mostly around the introduction of various rhetorical

modes of nonfiction essay writing, paragraphing,

organizational strategies, and the development of

author voice. There is an early introduction of

analytical reading and the concepts of objective and

factual summaries vs. analytical evaluations of

various writings.

EC2 was built around contemporary global

literature. It adds academic research, which

involves research strategies, various schools of

literary criticism, Modern Language Association

(MLA) citation methods, strategies for writing long

papers, and other elements. The learning outcomes

from both courses are fairly well defined for the

respective colleges for transfer, and the skill sets

expected from both have clear definitions in various

master course outlines. These learning objectives

must be left intact in any redesign, but new

learning may be added to enhance the courses. A

cultural redesign also strives to make the existing

learning more accessible for a wider range of

learners. The original course was built around the

use of contemporary international literature as a

basis for the research writing.

Redesign Strategies: English Composition I

English Composition I involves a reading and a

writing strand. The readings expose readers to a

range of ideas and topics. The learners explore a

variety of individual and public voices. They learn

various ways to summarize and analyze college-level

readings. They acquire new vocabulary. Students

form a sense of open-mindedness to others’ ideas.

The writing strand emphasizes self-expression and

the discovery of a personal voice. Learners

practice pre-writing, outlining and organization,

thesis-writing, various literary techniques,

point-of-vied, proper essay writing semantics, and

empowerment in building a public voice.

Online collection of contemporary essays.

For English Composition I, an online reader of a

variety of contemporary non-fiction essays was

created with live URL links. Learners were assigned

to choose a total of 12 essays throughout the

quarter to summarize and analyze—to enhance reading

analysis skills and the differentiation between

objectivity and subjectivity. The URLs were broken

up by rhetorical mode and sequenced into the

existing curriculum. This was to enhance reading

comprehension and analytical abilities.

This was also added to address an oversight in the

earlier curricular build, which left the course

without a reader and only a few brief essay

readings. The assignments highlighted

socio-cultural and historical assumptions underlying

the various literary works and therefore raised the

ability of learners to see others’ cultural ideas,

and more directly, their own. There were efforts to

avoid inaccurate, commercial, or fly-by-night

sites. Rather, the focus was on quality sites which

offered just the essays without excessive or

unnecessary add-ons.

Skills development.

Different assignments were created for the students

to focus on lead-ins and conclusions. More time was

spent on rhetorical modes and outlines. Writing

strategies were emphasized not only in the

curricular materials but also in the feedback of

learner works. The emphasis on extensive revision

was brought to the fore, in part to counter amateur

tendencies to go with just the first draft.

Clearly defined policies on civility, plagiarism,

and other relevant guidelines were created,

particularly given the academic nuances of these

issues. A slideshow on how to annotate readings for

helpful recollection and later analytical writing

was designed and written. A clearer explanation of

the course’s pedagogical theory - to enhance the

metacognition of learners - was created, with an

emphasis on study strategies and approaches. A

scaffolding piece on how to learn online was

included in the pre-week, to

help learners who are new

to this mode of e-learning.

Some other resources defined terms with greater

clarity, such as defining non-fiction vs. fiction

writing. Differentiating between facts and opinions

was addressed in one slideshow lecture. More

elaboration on the different genres of writing was

included. The use of

rhetorical mode forms to create a piece of organized

writing was built onto the course; learners were

introduced to both writing samples and strategies

based around narration, comparison and contrast,

description, definition, analogy or extended

comparison, collage, division and classification,

causal analysis, and other modes. Using more

effective thesis statements was included.

Audience analysis as a starting off point for

writing a paper was introduced as a strategy. One

lecture strove to show how the different stages of

the writing process fit together. And at the

conclusion an e-portfolio analysis was included at

the end, to provide a way for learners to analyze

their own work and thoughtfully approach their

development.

Wider topic ranges.

While memoir writing was accepted, the learners

could also go to the other objective extreme and

choose less individual-focused writing topics.

Instructors would benefit from further readings into

Native American history, literature, politics,

culture, health, and other elements—in order to be

conversant on some of these issues.

Promoting learner interactions.

The interactive curricular build encouraged learners

to read and critique each other’s works and to

respond to each other in every forum. The idea here

was to broaden their

sense of possibilities in work and to learn from

each other’s writing strategies.

Research transition for English Composition II.

A folder focused on research as the transition piece

into the next course, English Composition II. This

involved a segment on research strategies, the

citation of primary sources, how to use online

databases, and also how to use libraries. Some

resources on Modern Language Association (MLA)

citation methods were created.

Other learner works.

Additional annotation was added to the student essay

sampler, with insights on style and writing

strategies. These annotations also enhanced the

accessibility of their works, and reminders were

included in the Announcements about this resource.

Current students were encouraged to write quality

works, with a perk as possible inclusion of their

works in this small in-class repository (with their

copyright release).

The essay assignments will connect more clearly to

community (two of the current four assignments

already relate to community), especially the

evaluative first essay and the research final essay.

Redesign Strategies: English Composition II

The premises of the English Composition II course

redesign were to strengthen learners’ understanding

of information, the different valuations of

researched and discovered information, its use in

research, professional research citation, and

research writing. The ownership of information and

their de facto ownership of their own writing was

also an important element. The goal was to empower

learners as authors and researchers.

EC2’s focus on literature may be off-putting to

learners of different cultural backgrounds because

so much of literature is based out of cultural world

views and time periods. So one adjustment was that

learners were allowed a wider range of author

selection for their term projects. Learners need a

sense of comfort regarding their reading milieu

especially given the relative rarity of reading in

today’s society. More “scaffolding” would make

visible the cultural assumptions behind the literary

works, the authors’ lives and times, the values of

the times, and potential embedded worldviews.

Pre-week transition materials and tasks.

An opt-in pre-week folder was set up in the

Assignments area. This

included transitional lectures on issues of ethics

in research, research strategies, ways to write

longer research papers, and schools of literary

critique.

Updated learning resources.

Some elements were revised for better quality

learning and up-to-datedness. These included “Tips

for Organizing Longer Research Papers,” “Schools of

Literary Critique” (with a new explanatory graphic),

“Avoiding Logical Fallacies,” and other related

handouts / lectures in EC2. These resources were

created for easy downloading and learner

comprehension, with the hopes that learners would

use these as resources into the future post-course.

Visual literacy.

One fundamental change involved a visual literacy

element. This lecture addressed the inclusion of

graphics, drawings, maps, tables, charts, graphs,

diagrams, timelines, photographs, and other

elements, in a broad way. This encouraged the

examination of visually delivered information. This

covered the need to have captioning and labeling as

well as clear citations in the Works Cited list.

This addressed what visuals may convey in a paper in

terms of learning and memory. Also, some principles

of including graphics in a research paper were

included. The idea was to include more

multi-sensory modes in learning and in the handling

of information.

A fundamental change came with the addition of a

visual literacy resource. Students occasionally

will drop images into their papers, but these are

often done willy-nilly and without a larger

sensibility about how images may convey, summarize,

highlight, or communicate information in rich ways.

This touches on “other ways of knowing” promoted in

multicultural learning.

Coherent research strategies.

Learners often do not have a coherent research

strategy, so they often end up with highly disparate

works that may be unrelated to their original

pursuit. A strategy lecture covered a more coherent

applied way to approach research, both primary and

secondary.

Another slideshow lecture addressed tools that may

be used to organize and present longer works -précis,

subheadings, transitions, and others. Given the

difficulty of in-text citation (both in-sentence and

parenthetical) for many learners, this was

addressed. The relation between the in-text

citations and the Works Cited list was also

emphasized. Other common errors - such as how to

cite one author with multiple works in a paper -

were addressed. New authors also have difficult

times differentiating their own writing from their

cited writing, so a new resource was created about

when to quote, when to paraphrase and when to

summarize.

Opt-in group assignment choice.

An opt-in group assignment for the third critical

essay was created which would give learners a chance

to communicate and interact with peers in the

writing of one essay with a shared grade. This essay

allows for use of personal first-hand

reader-responses to a piece of literature.

Addressing common domain fallacies. The

embedded schools of literary critique from the

initial course design can be quite difficult to

grasp. Many students assert that authors write a

work to fit a particular literary critique tool and

do not seem to realize that all literary critique

tools can be applied to all literary works—with

differing outcomes. Authors may write a work that

may seem conducive to certain critique, but they do

not generally write works to fit a certain school of

critique. Others will reverse engineer a literary

work and make assumptions about authors’ lives, even

without any factual support. Addressing logical

fallacies and differentiating facts and opinions are

crucial.

The author's hand in research writing.

New research writers also need support in

understanding the importance of the author

hand—originality, worldview, clear values in

selecting research—in the writing of research

papers. Amateurs and those from other cultures seem

to be comfortable letting a research paper merely be

a listing of ideas from other resources, and they

forget the importance of actual authorship.

A passive mitigation.

A more passive mitigation involved setting up a

learner lounge, a space just for learners without

instructor presence or intervention. However, just

the mere existence of this space often is

insufficient to encourage learner participation, so

designing and placing some resources in this lounge

may be conducive to learner use and forum

presence.

Early Results

The course redesigns have not themselves undergone

rigorous testing for learning efficacy. Anecdotal

support has been positive from the learners who’ve

taken the courses. Part of The Enduring Legacies

Reservation-Based Project involves regular and

constant support and monitoring of the learners.

Conclusion

Planning for when to revise and update the

curricular materials of both redesigned courses will

be critical in maintaining the quality of the

curriculum. This would suggest that having clear

documentation of the decision-making for the current

rebuild, a definition of the applied cultural

principles, and documentation about the

technological standards and software used, will be

critical for later work.

The work of retrofitting courses for cultural

sensitivities may be seen as a larger part of making

the courses more accessible, albeit along cultural

lines. Some strategies involve the following:

·

surfacing cultural differences in a safe learning

environment

·

creating a range of assignment options for learners

·

scaffolding the learning for accessibility,

technologies, developmental learning, and costs

·

affirming learners’ abilities and experienced lives

·

offering student work samplers for deeper peer

learning

·

creating opportunities for the development of

learning communities, group work, dyadic work, and

interactivity among learners

·

considering learner budgets in the course design

·

promoting the scholarship of the learners’ works

·

soliciting learner feedback for more

learner-responsive cultural course redesigns

·

(and) exhibiting instructional flexibility (to some

degree) regarding time and student work.

The application of universal design aims to improve

the cultural accessibility and intercultural

understandings of all learners taking the e-learning

courses. In this paper, the focus was on English

Composition I and English Composition II, with a

focus on Native American learners through The

Enduring Legacies Reservation-Based Project. The

learning and general principles from these course

rebuilds may apply to other course retrofitting

situations from a cultural angle.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Barbara Leigh Smith, The Evergreen

State College; Connie Broughton, Managing Director

of WashingtonOnline (WAOL), and R. Max. Thanks also

to the Society for Applied Learning Technology

(SALT) for showcasing the cultural sensitivities

work in 2007.

References

Aldrich, H.E. and Waldinger, R. (1990). Ethnicity

and entrepreneurship. Annual Review of

Sociology: Vol. 16. pp. 111 – 135.

Alexander, P.A. and Judy, J.E. (1988, Winter). The

interaction of domain-specific and strategic

knowledge in academic performance. Review of

Educational Research: Vol. 58, No. 4. pp. 375

– 404.

Boiarsky, C. (2005). Making connections: Teaching

writing to engineers and technical writers in a

multicultural environment. IEEE. pp. 47 – 53.

Cajete, G. (1994). Look to the mountain: An

ecology of indigenous education. Asheville: Kivaki

Press. p. 20.

Casalino, N., D’Atri, A., Garro, A., Rullo, P.,

Sacca, D. and Ursino, D. (n.d.) An XML-based

multi-agent system to support an adaptive cultural

heritage learning. International Conference on

Networking, International Conference on Systems and

International Conference on Mobile Communications

and Learning Technologies (ICNICONSMCL ’06). IEEE.

p. 224

Demmert, Jr. W.G. (2001, Dec.) Improving academic

performance among Native American students: A

review of the research literature. ERIC

Clearinghouse on Rural Education and Small Schools.

pp. 1, 3 and 4.

Enduring Legacies Course Redesign Report. (2007).

The Evergreen State College. pp. 1 - 6

“Geert Hofstede™ Cultural Dimensions.” (2008) ITIM

International.

http://www.geert-hofstede.com/ .

Hai-Jew, S. (2007, Jan. 31 – Feb. 2). Cultural

sensitivities in eLearning: Designing hybridized

eLearning for Native American learners through ‘The

Enduring Legacies Project’” (A Case Study). SALT

2007 New Technologies Conference. Orlando, Florida.

Kirkness, V.J. and Barnhardt, R. (2001). First

nations and higher education: The four R’s—Respect,

Relevance, Reciprocity, Responsibility.

Knowledge across Cultures: A

Contribution to Dialogue among Civilizations.

R. Hayoe and J. Pan, Eds. Hong Kong: Comparative

Education Research Centre, the University of Hong

Kong.

Kroc, R., Woodard, D., Howard, R., and Hull, P.

(1995). Predicting graduation rates: A study of

land grant, research 1 and AAU universities.

Association for Institutional Research Forum,

Boston. p. 8.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995, Autumn). Toward a

theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American

Educational Research Journal: Vol. 32, No. 3,

pp. 465 – 491.

Liaw, M-L. (2006, Sept.) E-learning and the

development of intercultural competence.

Language Learning & Technology: Vol. 10, No.

3. pp. 49 – 64.

McCarty, T.L., Lynch, R.H., Wallace, S., and Benally,

A. (1991, Mar.). Classroom inquiry and Navajo

learning styles: A call for reassessment.

Anthropology & Education Quarterly: Vol. 22,

No. 1. pp. 42 – 59.

Merina, V. (2005, Fall). Covering Indian Country:

The Internet: Continuing the legacy of

storytelling. Nieman Reports: Vol. 59, No.

3. pp. 32 – 34.

Osbourne, A.B. (1996, Sept.) Practice into theory

into practice: Culturally relevant pedagogy for

students we have marginalized and normalized.

Anthropology & Education Quarterly: Vol. 27,

No. 3. pp. 285 – 314.

Pewewardy, C. (2002). Learning styles of American

Indian / Alaska Native students: A review of the

literature and implications for practice. Journal

of American Indian Education: 41, No. 3. pp. 22

– 56.

Pewewardy, C. and Hammer, P.C. (2003, Dec.)

Culturally responsive teaching for American Indian

students. ERIC Clearinghouse on Rural Education and

Small Schools. p. EDO-RC-03-10.

“Proposal to the Lumina Foundation for Education.”

(2005, Aug. 18). Smith, B.L., Special Assistant to

the Provost. pp. 1 – 10.

Reyhner, J. (2002 / 2004) “American Indian /

Alaska Native Education: An overview.” Northern

Arizona University.

http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~jar/AIE/Ind_Ed.html.

Sabin, C. and Ahern, T.C. (2002, Nov.)

Instructional design and culturally diverse

learners. 32nd ASEE / IEEE Frontiers in

Education Conference. pp. S1C-10 to S1C-14.

Sanchez, I. and Gunawardena, C.N. (1998).

Understanding and supporting the culturally diverse

distance learning. In C.C. Gibson, (Ed.), Distance

learners in higher education. Madison, WI:

Atwood Publishing. pp. 47 – 64.

Shumway, J.M. and Jackson, R.H. (1995, Apr.)

Native American population patterns.

Geographical Review: Vol. 85, No. 2. pp. 185 –

201. “Student Feedback: What They Say about their

Courses.” (2006).

Swisher, K. (1991, May). American Indian / Alaskan

Native learning styles: Research and practice. ERIC

Clearinghouse on Rural Education and Small Schools.

“Teaching and Learning with Native Americans: A

Handbook for Non-Native American Adult Educators.”

http://literacynet.org/lp/namericans/intro.html

“Universal Design.” (2007, Nov. 12). Wikipedia.

Downloaded Nov. 20, 2007.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_design

|