A System for Integrating Online Multimedia into College Curriculum

|

Michael V. Miller

Department of Sociology

The University of Texas at San Antonio

San Antonio, TX 78249 USA

michael.miller@utsa.edu

| Abstract

This article argues for the extensive employment of multimedia in college courses, and also suggests that instructors jointly involve their students in the process of making such resources. To foster greater engagement, a way of thinking about multimedia within the context of a coherent online system is introduced. The article identifies the key components of this system (i.e., distribution, location, collection, conceptualization, and production), the precise ways in which various online services and tools fit into each element, and how facility can be developed in working with digital learning content across the system.

Keywords : video, graphics, slideshows, media, cloud, RSS, bookmarking, information

|

Introduction

As instructors today, we have literally at our fingertips a vast and growing body of course-relevant content which can expand student learning opportunities unimaginably beyond those provided in the conventional text and lecture-based classroom. These resources consisting of online video, information graphics, image slideshows, and combinations of these and other media, can be timely, informative, and provocative, are easily accessible, and have the potential to break down classroom walls and directly engage students with subject matter. Moreover, the current configuration of media-relevant software applications, much of which is both user-friendly and freely available on the Web, enables us also to produce learning content of our own on a significant scale. Important is the fact that these applications now allow us to bring our students, as well, into the creative process.

Working with online multimedia within an academic field can range anywhere from simply linking them to syllabi or class presentations to teaching a full course devoted to their development. Although the latter could become a staple within the curriculum of virtually any discipline, most colleges now provide opportunities to gain or sharpen media-relevant skills only at a distance from students’ majors. Journalism programs increasingly have come to offer digital production courses, but enrollment in these is largely limited to journalism students. Courses directed to the greater student population, on the other hand, tend to be taught by educational technology specialists who, while long on technique, may have little experience in applying media to specific fields. Students can thus learn the mechanics of creating slideshow presentations and shooting video, but their work will likely have little relevance to their academic majors.

However, the availability of inexpensive digital cameras coupled with the recent emergence of reliable, user-friendly online services and tools have virtually eliminated the steep barriers to entry that formerly characterized multimedia production, now allowing for the expansion of instruction into varied curriculum domains. These applications not only enable content-area instructors and their students to find and collect digital learning content on the Web, they can assist them in creating and distributing materials of their own. Indeed, in light of their simplicity of use, most faculty can become competent enough to teach multimedia skills without extensive formal training. In addition to examining applications that are both free and easy to learn, those that are highly portable in the sense of facilitating work across multiple computing platforms will be especially featured in this paper. Such cloud software programs permit movement from desktop to laptop and other Internet-enabled devices without having to download applications or transfer working files, and in so doing also foster easy collaboration among users.

The full integration of online multimedia into academic curriculum makes great practical sense. We have the technological capability to do so, and it is backed by substantial research showing that media-based learning materials can help students better relate to course concepts and principles in a variety of ways (see Berk, 2009, and Shank, 2005, for reviews of the literature). Moreover, students today cannot be expected to pick up on their own how to engage with multimedia. Although some no doubt fit the stereotype—quite independently making, taking, or reshaping images, graphics, and online videos—they are not nearly as computer savvy and media sophisticated as is commonly assumed. Indeed, most students do not seem to have much feel for digital technology beyond texting and Facebook, rather than being literate in the sense of having the ability to engage multimedia in productive ways (see Metros cited in Grush, 2011). Teaching with multimedia thus not only could enhance learning by conveying subject content, it would likewise go far in promoting media literacy if students were required to address such materials in the classroom (Daley, 2003 ).

However, we are still a long way from significant integration, much less near the point of teaching our students how to work with multimedia, as even simple employment to date has not been widely embraced by U.S. college faculty. Although data are scarce, it appears that only a minority of instructors is using these resources in their classes. For example, perhaps no more than one-fourth regularly teaches with even such basic content as video clips (Guidry & BrckaLorenz, 2010; Smith & Caruso, 2010 ), despite their great online abundance and the fact that students enjoy learning through them (Smith & Caruso, 2010). Indeed, students overwhelmingly indicate that they desire far greater technology and media integration than they now get in their classes, often reporting they have to power down in their use of digital technology for school work in comparison to how they incorporate it in the rest of their lives (Kaufman & Mohan, 2009; Nielsen, 2009; Prensky, 2005).

The distinction made a decade ago between instructors as digital immigrants and students as digital natives (Prensky, 2001) generally still seems valid, but does not in itself account for college faculty being so slow to incorporate multimedia. Many K-12 teachers are digital immigrants as well, yet they have been far more inclined toward involvement in media integration. Discussions with faculty at various colleges and universities suggest that the problem is not that they did not grow up with technology nor their lack of interest. Rather, reluctance most often seems to reflect uncertainty about what working with multimedia exactly involves. A common perception is that integration is a complex, messy activity difficult to master that will take time away from the routines they have established around research and publication. Many also wonder if their schools really value integration because so little is done to encourage it beyond offering an occasional faculty development workshop. Certainly, they are not likely to believe that improving instruction by doing so will make a difference in raise and promotion considerations.

While not addressing the problem of low or absent institutional support for integration, this paper does argue that teaching with multimedia is possible to achieve with reasonably modest effort. In other words, faculty can develop at least some proficiency in working with digital learning content without disrupting their other academic pursuits. My interest in writing the paper came while developing an undergraduate sociology course on multimedia applications last year. Course objectives were to outline the rise of digital technology and its revolutionary effects on human behavior, examine the rich learning materials now available on the Web, demonstrate the ability of multimedia to make abstract concepts and research findings more comprehensible, and also provide students with initial experience in creating discipline-relevant digital content (see Miller, 2011b for course syllabus). I had no trouble locating quality publications and video tutorials on the Web that dealt with each of these course objectives. However, little information was found anywhere which shed light on how to approach online multimedia as a coherent system of information generation and processing that faculty and students could easily work within in terms of moving back and forth between the large universe of materials on the Internet and their own coursework applications and creative efforts. This paper therefore attempts to describe the system in terms of its basic elements, as well as identify current software services and tools that can be productively employed within each system component.

Types of Online Media and Multimedia Learning Resources

Although variously defined in the literature, media and multimedia are regarded in this paper as forms of symbolic communication that are not predominantly text-based. Multimedia will refer to combinations of different types of media that appeal to more than one perceptual sense, such as images with text or sound, or moving images and sound. They consist of a variety of visually-based resources such as slideshows, videos, and information graphics, as well as simulations, video games, and virtual worlds, such as Second Life, although these are beyond the scope of this paper . A lso not included in this paper are various types of social media such as social networking sites, wikis, and Twitter, except to the extent that these vehicles serve as ancillary resources within the online multimedia system. Likewise excluded are animated GIFs and interactive models and demonstrations, as these are primarily limited to science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) disciplines, and can be found in abundance at various STEM- related websites ( e.g., see Wolfram’s Demonstration Project). Finally, t wo other types of interactive devices may likewise be of use to instructors and students, but will not be further addressed. The first are those providing direct analogies for understanding phenomena in terms of size and spatial relationships. Exemplars of this genre are If It Were My Home’s Country Comparisons and Disasters , BBC’s Dimensions , and Huang’s Scale of the Universe . The second are the many interactive calculators available online (e.g., using the Life Clock to predict a student volunteer’s age at death never fails to generate lively class discussion; for an extensive directory of calculators, see Martindale’s Calculators On-Line Center).

Table 1 provides a list of different types of media and multimedia and two online examples for each genre by three broad curriculum areas—STEM, business and economics, and social sciences and humanities. Instructors interested in integrating online resources into their courses will no doubt want to start with video, and perhaps audio as well, as they can be very effective for communicating important course concepts. Quality radio (e.g., American RadioWorks,Americana , and This American Life ) is plentiful, evokes rich mental imagery, and is easier to locate than video in light of its concentration at two primary sites (NPR and BBC). Materials more than a few minutes long are best employed as a syllabus-linked, outside-class resource that can be easily listened to while attending to tasks not requiring full concentration.

Although video is reduced to two major types in Table 1 for purposes of simplifying illustration, there is a wide array of genres that can have instructional value, including news-event footage, point-of-view messages, interviews, tutorials, class lectures, advertisements, clips from television episodes and films, as well as subject-related documentaries (see Miller, 2011 c, for a detailed listing of video and audio types along with numerous online examples). Such materials can be employed outright in class, edited and incorporated into class or online presentations, or simply assigned to students for out-of-class viewing (for an example of syllabus incorporation, see Miller, 2011a). Graphic and animated video versions are additionally identified in Table 1 under clips and shorts as they are becoming an increasingly popular way to package a great amount of information into a work.

Slideshows involve a series of photos, drawings, or graphics that are arranged in sequence and accompanied by text or voice-over. Slideshows are fairly simple to create and can effectively convey significant information about a concept, document key events, or tell compelling personal stories. Text-based versions are arranged within a presentation program that requires viewers to advance themselves through each slide (see, e.g., What the World Eats or Rape as a Weapon of War ), while audio slideshows are rendered as a video and typically voice narrated (see, e.g., Six Months After the Pakistan Floods or A Teacher’s Bone Transplant Lesson).

Information graphics, also called infographics, have emerged from the field of data visualization and are on the Web today in great abundance largely due to the growing interest among online newspapers and magazines in employing visual data to complement reportage ( for background on the growing use of this genre in reporting, view Journalism in the Age of Data ) . They can range anywhere along a continuum from incredibly simple to incredibly complex, and although they can be categorized in a number of ways, this paper will draw distinction among them only on the basis of interactivity (see Segel and Heer, 2010, for a quality overview of the field). Excellent infographics—whether interactive or not—share the trait of providing a large amount of useful visual information in a highly economical way. Many infographics are not media-rich per se, describing information in quite straightforward ways through words and images (see, e.g., 10 Levels of Intimacy in Today’s Communication or History of Search) or in words and images combined with quantification (see, e.g., The Facts About Bottled Water orFive Years of History in Online Video). But even static infographics can be provocative by virtue of the details and connections they draw (see, e.g., Left vs. Right) or through combination and video animation (see, e.g., Geography of a Recession).

Table 1. Examples of Media and Multimedia by Type and Curriculum Area

The power of information graphics is most evident, however, when they are interactive. F or example, CNN’s Casualties graphically displays the distribution of U.S. and coalition service men and women killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. This resource contains among a number of features, a photo and basic information about each individual, including circumstances of death, a timeline, and maps linking their deaths in Iraq or Afghanistan to their hometowns. It is updated with each new death, and allows for friends and relatives to give relevant testimony. Also rich in detail, but for a war fought a century and a half earlier, The Washington Post’s, Battles and Casualties of the Civil War , displays a record of battles fought over historical time, and casualties suffered by each side. Text accounts are provided by clicking the battle circle, and progressively more battle mapping detail can be had by moving the slide to closer locations.

The last major multimedia category listed in Table 1 illustrates the power of using an aggregate of rich-media genres to tell a story or relate to a subject. The University of Utah’s Learn.Genetics site is comprised of numerous detailed, interactive tutorials consisting of narrated, user-driven slideshows along with a series of information graphics to effectively convey a gamut of concepts central to an introduction to genetics. Video more often serves however as the primary source of content with support from slideshows and/or information graphics. For example, Death Perceptions mixes video and various graphics to examine deaths by trauma in Columbus, Ohio. Particularly riveting are the video accounts provided by workers playing key roles in dealing with such victims . Focusing on one particular event, the 2007 Interstate 35 bridge collapse, the StarTribune’s 13 Seconds in August begins with a series of slides and sounds from the structural failure, and then proceeds to a panoramic image from above showing the wreckage site. Each vehicle is numbered, and clicking on it provides a text narrative about what happened to driver and passengers. The work is made especially poignant by links to videos of survivors providing accounts of their experiences during the event and family members talking about loved ones killed in the collapse. While developing such sites as these tend to involve more advanced software applications than most instructors who integrate multimedia would probably like to learn, they nonetheless serve as rich learning materials for courses, as well as providing high standards for ambitious students to emulate.

Conceptual Framework: Online Multimedia System

The development of educationally-relevant multimedia traditionally has been viewed as a highly deliberate process designed to create meaningful instructional materials to remediate patterned deficiencies in student learning. From this perspective, multimedia resources are the episodic end product of bureaucratically-administered projects. For example, a recent article published in this journal (see Frey & Sutton, 2010), based on extensive literature review and consultation with experts, proposed an explicit ten-step process centering on formal operations related to such considerations as needs and goals definition, instructional design, logistics, learning resource production, implementation, and post-assessment.

However, my framework considers multimedia development within the context of the operational environment of the Internet and available online services and software tools. Multimedia resource production is not defined in terms of occasional organized efforts specifically designed to ameliorate officially sanctioned problems, but rather as something that instructors and their students can fluidly create on an ongoing basis in order to enhance course content and learning. Importantly, as suggested, it sees the Web as an immense storehouse of potentially pertinent materials that can be appropriated, chunked and/or aggregated, repurposed, and used, reused, and shared.

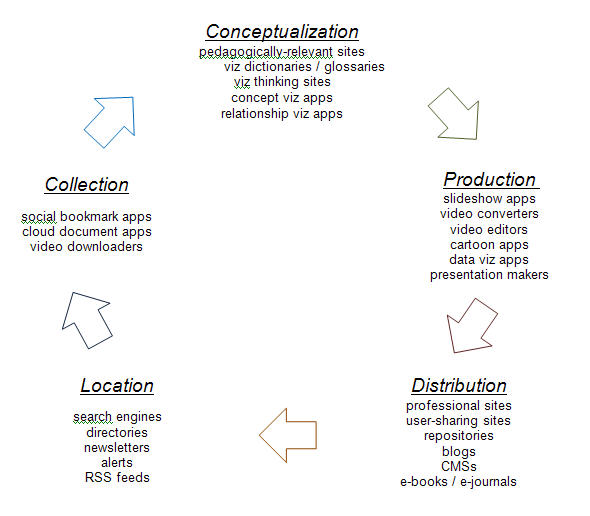

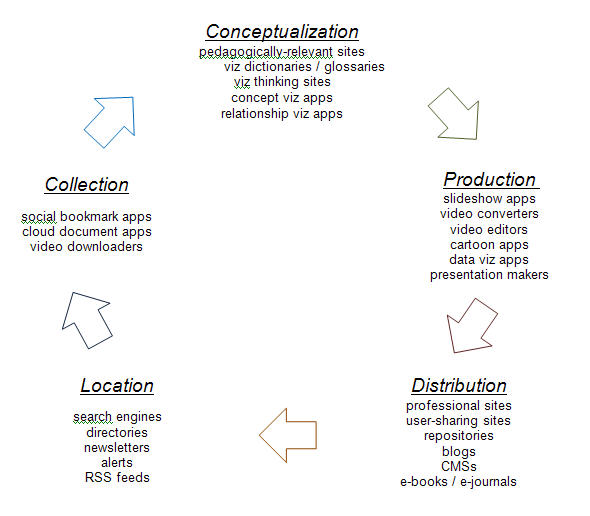

In my opinion, working with digital learning resources, whether it be producing them or simply linking them to a syllabus, is best facilitated by conceptualizing online multimedia within the context of an information generation and processing system. This system is comprised of five broad activities functionally linked within an ongoing cycle, specifically: distribution, location, collection, conceptualization, and production (see Figure 1). In examining the nature of each of these components, discussion will also center on those downloadable and cloud applications having the greatest potential to promote integration by virtue of providing acceptable quality, while being open source and simple to learn and employ. In addition, the online environment also includes legal and ethical considerations about which faculty and students should be mindful, particularly if they are interested in distributing their work on the Web, and therefore relevant resources about them will likewise be discussed.

Figure 1. Online Multimedia System

Distribution

Distribution makes digital content available for instructional purposes by placing it on the Internet. Prior to the recent explosion in bandwidth, user-sharing sites, and cloud services and tools, it was an activity almost solely engaged in by news and entertainment networks and educational media foundations. Such commercial outlets as ABC News, Guardian, The New York Times, Scientific American, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post, provide much of the digital multimedia that those beginning to integrate will likely employ in their courses. Materials available through many nonprofit distributors, such as Annenberg Learner, Link TV, PBS , NESTA , and NPR, likewise reflect high production values and have consistent classroom relevance. Some universities and research institutes have also developed excellent websites rich in multimedia for given areas of study (e.g., Serendip and DNA from the Beginning, respectively ).

However, the widespread emergence of user-sharing sites, such as YouTube, Vimeo, SlideShare , and authorSTREAM, within the last few years has radically altered the nature of distribution by making it possible for individuals to upload and make available what they have produced, repurposed, or simply appropriated from other sources. These sites have generated massive collections of media and multimedia within a short time, reflective of the growing availability of cheap cameras and open-source software, and also because slideshows and videos are difficult to share via e-mail, given prohibitively large file sizes. All of these hosting sites enable producers to upload their work, which can then be accessed via URL and streamed or downloaded. In addition to furnishing a wealth of material for classroom use, they likewise can be of value for storing and disseminating work produced by instructors and students. Many offer premium services with paid subscription, but they also provide no-cost versions that usually allow for generous uploading. Facebook, Myspace, BlackPlanet, and other social networking sites now similarly provide free uploading services.

Repositories are an additional source of digital learning content. However, with a few notable exceptions, such as the public-domain Internet Archive mega-site, they typically do not directly upload and store works, but serve to link resources located elsewhere on the Internet to focused audiences of potential users (e.g., for the major clearinghouse for college course offerings available online, see Academic Earth; for an extensive set of math and science video tutorials, see Khan Academy). Some also provide value-added functions such as peer-review ratings and commentary, or instructions about how specific multimedia can be productively employed within a course. Both Connexions and this journal’s parent organization, MERLOT, allow open access to massive bodies of digital teaching materials that have been submitted by instructors from across the curriculum over the past decade. A special feature of MERLOT is the rigorous evaluation afforded many submissions (see Become a MERLOT Peer Reviewer). Within sociology, TRAILS is a new repository similar to MERLOT in providing peer reviews, although not open source in nature.

Special online collections of video clips have also emerged in recent years. Many are only accessible through fee-based subscription (e.g., British Pathe, NBCLearn, and Prendismo, formerly Cornell University’s open-source eClips), but a few offer highly relevant linked clip resources at no cost. Among these, Mindgate Media is preeminent in providing a large inventory spread across the college curriculum. Moreover, Mindgate’s clips are often accompanied by lesson-use directions contributed by instructors who employed them in their own classes. Additional new services that do much the same as Mindgate, but are specific to given disciplines, include the excellent sociology site, Sociological Cinema , Economics of Seinfeld , Psychotube , and Veritasium . Critical Commons is a new open-source advocacy site that also offers critical-media commentary on provocative film and television clips.

Blogs have become an additional source of distribution as they not only link much multimedia that have appeared elsewhere on the Web, but also serve to distribute newly-created work. This is particularly the case for information graphics, as much material crafted by individual developers in search of an audience is contributed to such blogs as Infographics Showcase and Information Is Beautiful. Instructors and students should also be aware of blogs within their own academic disciplines that are devoted to multimedia. For example, the University of Minnesota through its umbrella sociology site, The Society Pages, sponsors useful blogs addressing videos and photo images (Sociological Images), infographics (Graphic Sociology), and audio recordings (Office Hours). Like MERLOT and the video clip repositories mentioned above, blogs typically provide some value-added function such as commentary or criticism about the media piece.

It should be mentioned that course management systems (CMSs, also called learning management systems) provide a distribution alternative to the Web for instructors to employ. There are a range of these available through purchase (e.g., Blackboard), textbook adoption (e.g., Pearson’s MySocLab), and open source (e.g., Moodle). In addition to providing a central place to store digital learning resources, CMSs offer instructors significant control over them through password-protected access, which may be important for those not wanting multimedia they have uploaded to be available to the public.

Finally, the growing movement to integrate multimedia into digitized versions of academically-oriented printed materials should be noted. Text publishers certainly are beginning to include links to multimedia in their e-book offerings, although access largely remains available through purchase only (for exceptions, see OER Commons ; for an open-source business model along with links to free texts, see Flat World Knowledge ). Doubtless, publishers understand that their titles will have to fully integrate interactive media in order to be competitive in the near-future college market (for a demonstration of the potential of digital books, seeMatas (2011, April) ). Academic journals also are increasingly becoming digitally accessible, although relatively few journals that have gone online thus far have capitalized on the tremendous opportunities for multimedia integration that this presents. Most simply provide PDF versions of text-based articles. Disciplines on the leading edge in this regard generally are those for which visual and/or audio representation are particularly crucial for communicating subject matter (see, e.g., Eyetube, Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, Journal of Visualized Experiments, and Video Journal of Orthopaedics ), as well as those journals which incorporate topics about the development and application of digital multimedia (see, e.g., Audiovisual Thinking , Computers and Composition, Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, and Vectors: Journal of Culture and Technology in a Dynamic Vernacular).

Location

If instructors and students are to develop proficiency in working with multimedia, they must become immersed in the online environment. They will need to be familiar with those websites that consistently distribute the best work across various genres that relate to their academic disciplines, as well as stay abreast of the continuous output of digital materials that can be put to use in their courses. Obviously, cyberspace is vast, and searching for resources there without assistance can be a daunting task.

Productive immersion and location of online materials pertinent to any academic discipline are facilitated by a variety of vehicles (see Figure 1). Search engines constitute the most popular one for finding media in general, and specialized search engines are particularly relevant for photos and videos, with Google sites specifically devoted to each being the most comprehensive (see Google Images and Google Video ; also see Timeline and Wonder Wheel , additional visual Google search tools). User-rated “discovery engines,” such as StumbleUpon and Digg , may also help locate multimedia which have gathered popular currency. Searches can likewise be conducted at user-sharing sites such as YouTube and SlideShare, but only materials housed within those websites will surface. The location of instructor-crafted learning objects and videos that include lesson plans generally require search at link-based repositories such as MERLOT and Mindgate Media.

Directories can likewise be useful for finding publication and distribution sites, specific digital resources, as well as materials which could be used to compose resources. For example, free stock-photo and open-source image sites are listed at AnimHut (see Ganesh, 2010). Useful information graphics directories can be found at Alltop: Infographics and Smashing Magazine, which recently published an extensive overview of infographic blog and producer websites (see Chapman, 2009). For video directories, two of the most comprehensive are Digital Librarian (see Anderson, 2010 ) and my article published recently in The MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, which probably contains the most extensive listing to date of relevant websites, programs, and clips (see Miller, 2009, Appendix E, pp. 408-423).

Newsletters and alerts comprise effortless ways to find multimedia learning content. Many distributor organizations e-mail free newsletters to subscribers on a periodic basis. Two that have served me well are the PBS Teachers Newsletter, which announces weekly programming to be aired on that network (sign up at My Profile), and The New York Times Focus, providing links to all slideshows, infographics, and videos deemed significant by editors that appeared in online Times editions the previous week. Also, Google Alerts is an excellent service for deriving topic-specific announcements about multimedia that have been posted to the Web.

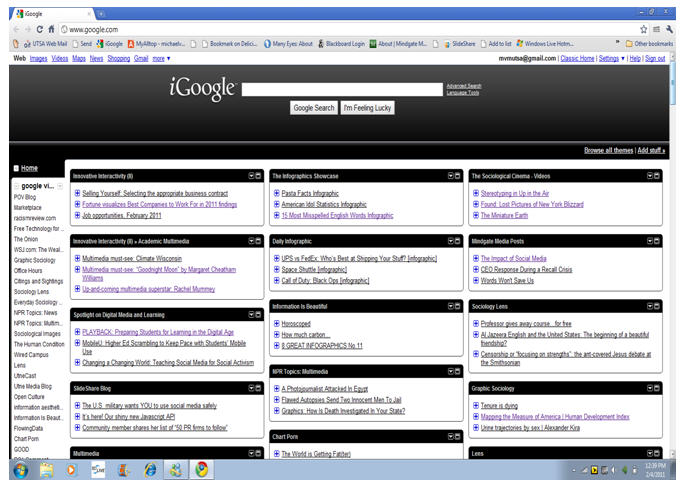

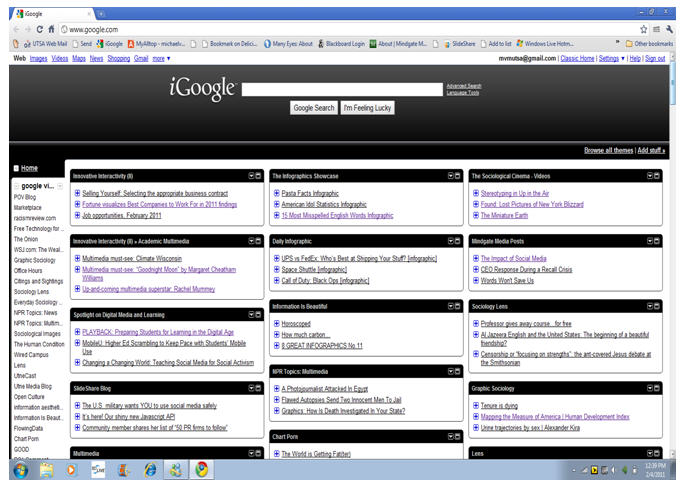

Perhaps the best and simplest way to facilitate location, however, is by creating a multimedia homepage comprised of push vehicles such as RSS feeds. The utility of the RSS widget is that it minimizes time and effort devoted to search activity by automatically forwarding new links from commercial distributors, user-sharing sites, blogs, and aggregators. These works may then be directly accessed from one’s homepage and examined on a periodic basis for relevance and value (for instructions on creating a multimedia homepage, see Miller, 2010a). Figure 2 shows a screenshot of an iGoogle homepage that could serve as the primary vehicle for locating online resources and media-relevant articles. This homepage example includes over 100 websites, with each highlighting the latest three materials featured on the site. The more productive a website, the more frequently entries change, and entries already visited are differentiated by font color from unvisited ones. Moreover, the left-hand margin of the page provides a complete list of websites that are being tracked; clicking on any of these reveals a list of all story feeds that have been received over time from a given website. RSS widgets on the iGoogle homepage also can be dragged and dropped to change locational prominence or categorical grouping, and of course can be deleted if unproductive.

Figure 2. Multimedia Homepage

Collection

What is to be done with an online resource once found and deemed worthy of keeping is the question addressed within the collection realm (see Figure 1). Location vehicles will uncover on an ongoing basis significant amounts of course-relevant materials that faculty and students may want to inspect and ultimately use. However, without a viable approach to collection, the process of managing digital links can become chaotic and time-consuming. C ollectors in many academic disciplines will no doubt be faced with the problem of resource overabundance, and therefore will need to devise relevant working criteria in order to limit and bring coherence to this activity. Titles and URLs will also need to not only be systematically recorded, but catalogued in such form that they can be efficiently retrieved on demand. Instructors and students may likewise want to have a copy of video files in their own possession, typically for reasons of later repurposing. This is an additional aspect of collection that can be handled through downloading tools such as RealPlayer.

Social bookmarks provide the most efficient mode for both collecting and organizing a large body of online multimedia. Although there are a number of free applications that serve these functions (e.g., see, Delicious , Diigo , and Zotero ), Google Bookmarks is my collector of choice. Generated categories for sociology courses that are taught, as well as various topics related to the nature and use of digital media, along with other subjects of interest, allow for the efficient cataloguing of articles, multimedia, and sites as encountered on the Web. For categories that have large amounts of entries, subcategories may also be designated to simplify organization (e.g., see the Work and Economy listing). Each entry can then be tagged to provide further details facilitating efficient retrieval. Google Bookmarks also includes an “add to list” feature that allows users to directly bookmark to category without copying and pasting its URL, and an access function which provides for variable bookmark sharing.

In addition to bookmarking, collectors may want to keep updated notes about particular learning resources and related integration issues. This can become unwieldy for those who use more than one computing device by virtue of having to transfer the working document file from one unit to another via flash-drive or by e-mailing it to one’s self as new entries are made. However, cloud technologies provide more efficient ways for handling this task through online document applications such as Google Docs or hosting / synchronization services such as Dropbox .

Conceptualization

Conceptualization involves the development of ideas and operations that determine what will be linked, repurposed, synthesized, or created from scratch, and how such products will be applied to learning. At the minimum, conceptualization should draw from a mix of at least three areas: form (principles and practices of multimedia design), content (substance of academic discipline), and purpose (instructor pedagogical objectives). In addition, conceptualization efforts may benefit from the employment of online applications that serve to stimulate thought about building and using multimedia. Such creativity tools as concept maps and graphical dictionaries can help instructors and students better visualize concepts and concept relationships.

Instructors interested in integrating multimedia into their courses might start by becoming familiar with at some of the sites that specifically address the use of multimedia within the context of teaching and learning (see, e.g., 21st Century Fluency Project, Free Technology for Teachers, HASTAC, MacArthur Foundation , MindShift , and Digital Learning Environments ). Andrew Churches’ adaptation of Bloom’s Taxonomy to Web-based media instruction is especially useful in this regard. His Digital Taxonomy organizes various activities related to multimedia creation and employment within Bloom’s famous higher order / lower orderthinking skills framework (see Summary Map), as well as in terms of types of tools, software applications, and rubrics identifying learning criteria.

Conceptualization about multimedia form includes consideration of multimedia principles (see, e.g., CognitiveDesignSolutions, 2003; Mayer, 2003, Shank, 2005) and other dimensions of design that facilitate learning goals, including functionality, aesthetics, and usability (see Clark, 2011). An important part of becoming conversant about design requires familiarity with the work of others. Gaining fluency in this regard would certainly benefit from close inspection of online examples that are thought to be exemplary. Studying the work of professional developers at sites such as The New York Times and the Guardian may stimulate creative thinking about the best ways to approach discipline-relevant concepts and data. As mentioned, a number of blogs are devoted to the critical evaluation of information graphics at a general level, as well as for work crafted within some disciplines (e.g., ongoing critiques about design are available at Graphic Sociology). Revisiting repositories such as MERLOT to see how multimedia there have been produced or repurposed should also help design efforts.

If interested in developing multimedia relevant to disciplinary content, fundamental understanding about the nature of inquiry within the field is essential. For example, those working in any science should be conversant about the linkage between explanation and evidence. Reacquainting students with theory and the process of empirical verification--particularly in terms of conceptualization and measurement, data collection techniques, data analysis and interpretation, and establishing causation--would be a wise investment of time and energy. In preparation for discussions about these considerations, social science majors might review online modules such as Critical Thinking Web or Quantitative Methods in Social Sciences.

The employment of online multimedia certainly should be informed by how media has been traditionally incorporated into the academic field in question. For example, sociologists have long been interested in using disciplinary perspectives and methods to understand the content of newspapers and magazines, advertising, popular music, radio and television programming, and movies, and also have extensively employed photos, audio recordings, and video to describe and analyze behavior. Online resources can be similarly used as an object of study and as a data-gathering source, in addition to serving as an instructional vehicle.

Of course, the value of a piece of multimedia does not lie in the resource itself, but rather in how well it facilitates instruction and meets student learning needs. Pedagogical objectives therefore should necessarily inform multimedia development and employment. Online video has been extensively addressed in this regard in recent years (e.g., see Andrist, Chepp, & Dean, 2011, Berk, 2009 and 2010, Burden & Atkinson, 2007, Duffy, 2008, King & Cox, 2011, Miller, 2009, and Zhao, 2011; almost forty scholarly articles and conference papers have been devoted to just teaching with YouTube, according to Snelson, 2011). These writings provide a wealth of ideas as to how video resources can be employed to promote learning goals, and similar instructions about using audio and information graphics have likewise begun to emerge (see Sayers, 2010, and Wynn, 2009, for the former, and Schulten, 2010, for the latter). Sites centering on the promotion of visual thinking, such as The Back of the Napkinand XPLANEIVisualthinking can stimulate ideas about pedagogical application, as can those which enrich voice narratives through illustration, such as RSA’s Animates, and the several videos produced by StoryCorps (e.g., see The Human Voice). Sites that offer experimental approaches to modes of presentation also bear examination (e.g., Igniteand 60-Second Lectures).

In addition to the representation of key course concepts and principles, video clips can serve numerous objectives that include, among many others, showing the real-world relevance of abstract content (The Math Behind Numb3rs), illustrating the power of elegant explanation ( Explaining Stonehenge ), injecting humor into a drab topic (Troubling Rise in Teen Uranium Enrichment ), enhancing appreciation of alternative viewpoints (Stolen for Fashion), promoting affective learning (Cab Driver to Donate Kidney), and even preserving instructor time and sanity (AmyMaalox (2010, November 12)). Of course, linked online documentaries, as well as clips, can be used effectively outside the classroom to augment depth and detail of content covered in class.

Instructors should also visit those websites that have been created to facilitate the distribution and employment of multimedia for instruction. This definitely would include close examination of curriculum–relevant resources in MERLOT and those in narrower learning object repositories such as Connexions, as well as video clips and instructional materials available at Mindgate Media and the various discipline-specific sites previously mentioned. All of these websites not only filter through the massive amount of multimedia available on the Web to identify and provide materials that are especially pertinent for instructional use, but moreover facilitate teaching by detailing how such media can be productively used in courses.

Also of relevance for conceptualization are a variety of creativity tools now available on the Web. Among the many dictionaries and glossaries, Wordnik provides usage examples from the Internet, recent Twitter references, relevant photos tagged in Flickr, and a charts feature, consisting of ratios of a word’s appearance in digitized text over historical time. Graphical dictionaries may also be helpful; they display terms in webbed linkages in relation to synonyms, antonyms, and related word forms (Visuwords and Lexipedia). Video dictionaries (e.g., Wordia) and encyclopedias (e.g., Encyclopedia of Usability) represent the latest reference variants.

Moreover, creativity tools relevant to methods of visualization can be especially helpful for encouraging systematic thought about how discipline-specific concepts and relationships can be framed by multimedia. Lengler and Eppler define a visualization method as a "…systematic, rule-based, external, permanent, and graphic representation that depicts information in a way that is conducive to acquiring insights, developing an elaborate understanding, or communicating experiences…" (2007a, p.1 ), and have created an interactive table, organizing exactly 100 devices across six types of visualization categories (see Lengler and Eppler, 2007b). Patterned along the lines of the well-known chemistry table, this highly instructive work provides an excellent beginning for understanding the diversity and utility of visualization (see A Periodic Table of Visualization Methods). Data visualization is an especially relevant type of visualization method for those in STEM and social science disciplines, and many useful guides are available online to provide introduction to this field (see, e.g., Few, 2010; for specific help about teaching with visualizations in the geosciences, see SERC, 2010).

For explicit treatment of concept relationships, instructors and students might likewise become familiar with concept-mapping tools (see also closely related mind-mapping and argument-mapping tools). Rather than providing sets of terms, meanings, or links as do online dictionaries, these devices help users graphically lay out ideas and link them to related concepts of choice (see Novak and Canas, 2008 for basic description). Such maps may assist conceptualization efforts by forcing users to explicate their ideas, help to clarify thinking about relationships between ideas, and promote communication with others about such relationships. Most of these tools also allow for the embedding of hypertext links to online materials. Nonetheless, online concept-mapping applications require more than a few minutes to learn as procedures tend to be complex (see Eppler, 2006, for discussion of strengths and weaknesses, as well as an elaboration of concept map variants). Cmap is probably the best known of the more than two dozen freeware versions now available.

Production

Production, of course, is at the heart of the online multimedia environment, and now is no longer limited to just those with specialized media skills having access to costly equipment and software. As mentioned, full immersion in the production process is certainly not essential for instructors who simply wish to use online materials in their courses. They can quickly learn how to link such content to syllabi or class presentations. However, as they become more proficient with integration, they may want to create their own works and possibly teach production to their students. There are now a wide variety of no-cost downloadable and cloud applications to facilitate production of various kinds (see Figure 1).

Instructors today can employ online multimedia in their classes in virtually limitless ways with varying degrees of complexity. Generally, the nature of integration sought is dependent on pedagogical goals as determined in the conceptualization stage, as well as instructor proficiency in working with digital resources and software. Facility with production can be viewed as an acquired, additive process along a trajectory that begins with linking activities and then extends to more complex and involved kinds of repurposing and creation.

Instructors who have yet to use online materials should start with linking, i.e., directing online resources to students via hypertext links. Linking involves no activities that download or in any way alter online multimedia, nor does it risk violation of copyright law ( American Library Association, 2006 ) . Linking can be performed by inserting a URL either on a course document to be made available to students online or on a slide within a presentation to be shown in class, posted on a CMS, or uploaded to a user-sharing website. As previously mentioned, the assignment of online resources linked to a course syllabus is an especially efficient way to augment out-of-class learning for students (see, e.g., Miller, 2011a ).

Those experienced in using streamed media through linking might build on this by repurposing existing online materials or by creating new resources for their courses. Pro duction comes in varied forms: it can be built around downloading and transforming extant online images, videos, and/or sounds into a synthesis or mash-up, creating the substance of one’s work by shooting and editing, or inputting directions or data into a cloud application which in turn performs the bulk of creative activity.

There are several good starting places for acquiring development skills beyond linking. One would be to become familiar with visualization applications that render simple output such as word clouds (see Wordle ) or photo mosaics (see Mosaic Maker ). Instructor or student-authored work could be used for various class purposes (e.g., see Borash, 2011) , for how word clouds can illustrate change in learning comprehension, or see admin, 2011 , for how they can draw comparisons between groups; relative to photo mosaics, see soconceptual (2010, August 20) , for how they might serve as a student introduction device). Initial activities could likewise center on presentation development. For example, one could start by adding voice narration to existing course presentation slides used in the classroom (Donavant, 2011). These could then be uploaded to the CMS or to a user-sharing site for future student reference. A slideshow with either one’s own images or those acquired online could also be created. User-friendly Photo Story 3 allows for customized image motion and voice-narration / music insertion (if using a Mac, slideshows in addition to other video-related work can be handled by the preloaded iMovie program). While this application is only available via download, cloud alternatives are VoiceThread , which provides for collaboration by recording viewer reactions to slides, and PhotoPeach , which allows for a quiz component (see slideshow example and Bentley, 2010).

Producing work that involves video integration can be easily handled through Windows Movie Maker, another free downloadable Microsoft application. However, if instructors or students are interested in repurposing existing online video and incorporating it into a presentation, converting the clip to a compatible format that can be edited is first necessary. There are a variety of converters available on the Web at no cost: e.g., the latest version of RealPlayer includes both downloading and converting functions, and the free version of Any Video Converter is quite serviceable, particularly if the video segment to be edited is lengthy or has already been downloaded (for detailed steps on how to use this program, see Miller, 2011d). Once the clip has been converted into an appropriate format, it can then be imported into the video editor. Preliminary to this, however, instructors and students will likely want to edit images and sound before inserting in video—tasks that can be handled through online applications such as GIMP or Picasa and Audacity .

Windows Movie Maker (WMM) has features that can be intuitively grasped to produce video presentations. It is free and allows for standard video production functions: effects, transitions, timeline editing, text insertion, and audio file editing (note: the latest version, Windows Live Movie Maker, has been criticized widely (e.g., see Henry, 2010), and those having Vista or Windows 7 operating systems might instead upload an earlier variant, WMM 2.6). Instructors should also be aware of the large body of free, online tutorials, providing suggestions and tips about how to employ the program (see, e.g., Russell, n.d.). My students have used WMM to good effect in repurposing extant online video, and in shooting their own footage (see, e.g., soconceptual (2011, June 3)). While WMM is only available through download, two others have recently become accessible from the cloud: JayCut andYouTube Video Editor , although limited to editing videos from that site.

Instructors should also be aware that the employment of video can be extended through cloud applications to the production of animated cartoons. One of the most user-friendly is xtranormal . Students in my multimedia applications class were asked to outline a two-person dialogue around a significant social issue (the free version of xtranormal permits no more than two characters). They then developed a story plot that included voice script and character movements, and entered it into the cartoon development site. They were able to produce credible submissions after briefly working with the application, and were overwhelmingly positive about its potential as a creative instructional tool (for an example of student work, see soconceptual (March 7, 2011)).

For those instructors who are quantitatively inclined, an assortment of cloud applications permit the facile production of information graphics output. These range from those with limited functionality such as timeline creation (e.g., xtimeline and TimeGlider), to those having multiple display utility (e.g., Google Fusion Tables , Many Eyes , StatPlanet , and Tableau Public ). The latter type allow users to upload their own data or data provided at the site, and then produce various kinds of visual graphics, including text analysis, frequency distributions, time-series distributions, and mapping. These programs have varying strengths and weaknesses, as well as degrees of difficulty to master. Given sufficient time, instructors might attempt to employ Tableau Public as it is clearly the most sophisticated, permitting the construction of interactive infographics. Conversely, Many Eyes will likely be the program of choice for most instructors and students as it is the most user-friendly. Those who want to display time-series analyses relating to specific locales should definitely become familiar with Gapminder . This dynamic tool is useful for making highly animated state and international comparisons over historical time relative to a large collection of population, health, and economic variables (see the developer's introduction at Rosling, (2006, February)). Gapminder is quick and easy to learn, and is available through download and on the cloud (for a detailed lesson plan about how to employ Gapminder in the classroom, see Lindgren, 2010).

It is important to note that virtually all areas of media production are complemented by numerous online publications and tutorials providing explicit details about how to produce quality work with given types of applications. For example, Knight Digital Media Center hosts an extensive set of informative tutorials andworkshop presentations , as do es JISC Digital Media and Vimeo. Quality textbooks about multimedia development are also available online (see, e.g., Briggs, 2007 and Savage & Vogel, 2009 ).

Finally, instructors with students who may be unable to afford standard presentation software programs should be aware of no-cost alternatives. Oracle, for example, provides OpenOffice which is comparable to the Microsoft Office suite, and includes IMPRESS, the equivalent of PowerPoint. A significant alternative to PowerPoint is Prezi , which provides a very functional free version. In fact, Prezi is currently gaining wide popularity among presentation developers, given its departure from the linear nature of other programs by virtue of having an infinite canvas to work upon rather than being bound by sequential slides (see Colemere’s Imagine! and King’s A History of Hate for good examples of the potential of this application).

Legal and Ethical Considerations

The use of copyrighted work is an area fraught with confusion and anxiety for many instructors, although their students commonly believe that if it is on the Web, it is fair game. Because most online multimedia made in recent years is protected by copyright law, it is important to avoid infringement. However, this does not mean that copying and exhibiting parts of such works are by definition illegal. The fair use clause of copyright law grants limited privileges to certain categories, including college instructors and students (particularly those teaching or studying media), under given conditions (see Section 107 [U.S. Code, 2007]). In reality, fair use allows for the judicious employment of copyrighted work if the product being created from it is transformative in nature and will be used for noncommercial purposes.

Instructors should therefore make sure they and their students are knowledgeable about fair use and its boundaries. Guidance for this task is available through the Center for Social Media, an organization that has led efforts to widen fair-use latitude. The Center has developed a series of "best practice" codes concerning copyright and fair use, specifically directed at media instructors and online video and documentary filmmakers (see Center for Social Media: Fair Use), that include a set of downloadable teaching materials (see Center for Social Media: Fair Use Teaching Tools).

In addition to copyright, instructors and students need to know what is both legally permissible and ethically appropriate if they are to shoot and publish photos and videos. Certainly, they should be apprised of legal restrictions for public and private places. Laws specific to locale should be examined and discussed in class (preliminary to reviewing laws, students might be assigned Atkins (n.d.) and Krages (2006). Within this context, the importance of gaining subject permission should also be addressed; many colleges make consent and release forms available to faculty and students. It is likewise important for faculty and students to have an understanding of ethical issues relevant to photography and videography (NPPA, 2011, is a good starting point), and particularly the variability in attitudes and norms prevailing across subject-group populations about having their pictures taken (see "Approaching Unfamiliar Cultures" in Caputo, 2007).

Conclusions

This paper has outlined some of the basic considerations relevant to teaching with and about online learning resources. It has conceptually mapped the central elements of the online multimedia system and illustrated the relevance of these elements to integrating such instruction within academic disciplines. It has paid special attention to how facility in working with multimedia can be fostered and then employed by instructors and students to augment reading and lecture-based learning content. Online resources can be easily added to the arsenal of instructional materials that are either presented in class or assigned. As shown, cloud computing services and tools, which can facilitate collaboration and movement across Internet-enabled devices, are becoming increasingly available for use within components of the online multimedia system.

Instruction about how to create slideshows, information graphics, and video presentations with the assistance of online tools, moreover, can be integrated into virtually any course within a discipline. Instructors might consider employing media-production activities as either supplements or substitutes for common course requirements such as research papers. Faculty who have production skills could transition to teaching media development either within a regular course or by creating an offering explicitly centered on multimedia. Leading a class devoted to it of course assumes broad knowledge about how digital resources can fit into the academic discipline, in addition to having skills across all elements of the online system.

As suggested, production abilities can be acquired incrementally over time. Instructors new to using multimedia might first try linking materials to course syllabi or linking a video clip to a class presentation. Instructors who want to exploit multimedia definitely need to become familiar with the most productive discipline-relevant websites, and should establish a system of multimedia information processing like that outlined in this paper, which will enable them to facilely locate, retrieve, and catalogue resources. Moreover, they might likewise encourage students to begin using fundamental tools such as RSS feeds and social bookmarks for finding and collecting online information that are relevant to their academic coursework.

Online multimedia resources are obviously neither space nor time bound. They can be used within an equipped classroom or outside it at any time as long as students have access to an Internet-enabled device. Indeed, distance-learning instructors should find them particularly relevant in light of the common criticism that their teaching is too reliant on text-based content. Online multimedia would certainly go far in supplementing texts and streamed talking-head lecture videos, and assignments requiring its production would likewise be suitable as much of the substance of in-class instruction about media production could be handled through online tutorials created by instructors themselves or linked from the Web.

Experience gained in developing and leading a course devoted to applying Web-mediated learning resources to sociology suggests several recommendations for those having interest in offering a similar course within their own disciplines. Some relate directly to mundane considerations in managing class logistics and operating issues. For example, should the course be work-product intensive, enrollment should be low—perhaps no more than 15 students. Likewise, a well-conceived system for facilitating assignment submission flow and grading is essential, and can be managed through a serviceable CMS. For courses taught in a computer lab, it is wise to secure administrative privileges in order to download software without having to wait for permissions. Periodic assistance will no doubt be necessary to address technical questions as they arise. Therefore having someone to call on for quick answers should prove invaluable; indeed, cultivating a positive working relationship with a technology specialist or two is good policy. Consider also enlisting other faculty and staff who are especially knowledgeable about given media-authoring programs to serve as occasional guest instructors.

The most meaningful lesson learned from teaching a multimedia development course, however, relates to teaching style and orientation. Specifically, as instructors, we may need to revise possibly entrenched ways of relating to students in light of our status as digital immigrants. That is, many of us, unlike our students, did not grow up with current technology, and therefore will likely early betray our rather imperfect knowledge and clumsiness in relating to things digital. The probability that there will be some students in our classes who are more aware and skilled about some aspects of digital media, nevertheless, should not keep us from instruction. Rather, we might think of ourselves as facilitators, remaining vital by providing structure and guidance, but as well communicating to students that we see ourselves as mutual learners (see Grasha, 2002, and McGee & Diaz, 2007). Such leveling in authority structure may also help promote a classroom environment more open to experimentation, where students are more concerned about innovation than avoiding mistakes.

Developing competence in using and creating online multimedia not only should enhance students' academic comprehension and practical skill-sets, but also may have relevance to broader changes now emerging. Certainly, digital technology has challenged long-standing beliefs about the nature of education, especially in light of growing fiscal constraints and public demands for more flexible, cheaper alternatives. Online courses are now instructional delivery staples within many colleges, and their popular rise underlines the fact that schooling can occur in virtually any place at any time. Moreover, traditional icons of academic authority—the professor as expert, the peer-reviewed publication, and the course text—have likewise been challenged by the onslaught of online information resources. The increasing use of instructor and student-crafted multimedia may further add to this controversy. As demonstrated in this paper, we now have the capacity to bring online multimedia production fully into the curriculum, and should this occur on a widespread basis, we can expect far more debate as to what is an acceptable learning source and how should those who develop them be recognized. Organizations such as MERLOT will no doubt enter into this discussion, given their role in institutionally legitimating instructor-authored learning content through peer review.

Likewise consistent with emergent change is the potential for multimedia development to affect relationships with students. As we begin working closely together on projects, we will not only contribute to the growth of Web-mediated instruction and media literacy, but also may be promoting a constructivist alternative to the distant, hierarchical relationships now prevailing in undergraduate education. This emergent model would more clearly recognize the value of the experiences and latent abilities that students themselves bring into the classroom. Indeed, the significant growth of multimedia instruction across disciplines, sparked by the keen interest of youth in online activity coupled with their underlying dexterity in working with digital technology, may be one additional step toward making colleges more relevant and appealing to students in the near future.

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is extended to those colleagues who offered helpful reactions to earlier iterations of these ideas: John Bartkowski, Ron Berk, Ilna Colemere, Paul Dean, Juanita Firestone, Natalie Giesbrecht, Jeffrey Halley, Lisa Lewin, Patricia McGee, Cherylon Robinson, Chareen Snelson, Kyle Songer, Cathy Swift, and Jose Vazquez. I am particularly grateful to Barbara Millis, Director, Teaching and Learning Center, The University of Texas at San Antonio for her encouragement and advice over the course of the writing project. I would also like to thank the students in my classes for the many worthwhile suggestions they gave about conceptualizing multimedia content and working with online applications. Jessika Horner, Alexandria Inman, and Emily Johnson are especially appreciated for permitting me to link their work to the paper. Finally, LaVonne Grandy, Jason Fane, and Rick Schlueter deserve special recognition for the very competent technical assistance they have provided over recent years.

References

admin. (2011). Word cloud: How toy ad vocabulary reinforces gender stereotypes. The Achilles Effect. (March 28). http://www.achilleseffect.com/2011/03/word-cloud-how-toy-ad-vocabulary-reinforces- gender-stereotypes/

American Library Association. (2006). Hypertext linking and copyright issues. American Library Association. ( October 11). http://www.ala.org/ala/aboutala/offices/wo/woissues/copyrightb/copyrightarticle/hypertextlinking.cfm

Andrist, L., Chepp, V., & Dean, P. (2011). Using videos in the classroom: Pedagogy and the Sociological Cinema. Teaching / Learning Matters. 39(3), 8-10. http://www2.asanet.org/sectionteach/v39n3.pdf

Bentley, P. (2010). Comparing tools part 2: PhotoPeach. Cloud 9. (July 11). http://penbentley.com/2010/07/11/comparing-tools-part-2-photopeach/

Berk, R. (2009). Multimedia teaching with video clips: TV, movies, YouTube, and mtvU in the college classroom. International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, 5(1). http://www.sicet.org/journals/ijttl/issue0901/1_Berk.pdf

Berk, R. (2010). How do you leverage the latest technologies, including Web 2.0 tools, in your classroom? International Journal of Technology in Teaching and Learning, 6(1). http://www.ronberk.com/articles/2010_leverage.pdf

Briggs, M. (2007). Journalism 2.0: How to Survive and Thrive. Knight Citizens News Network. http://www.kcnn.org/resources/journalism_20/

Burden, K. & Atkinson, J. (2007). Jumping on the YouTube bandwagon? Using digital videoclips to develop personalised learning strategies. ICT: Providing Choices For Learners and Learning. Proceedings ASCILITE Singapore 2007 . http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/singapore07/procs/burden-poster.pdf

Clark, G. (2011). Four dimensions of multimedia. CAPP 30523 - Applied Multimedia Technology, Fall 2008. University of Notre Dame OpenCourseWare. http://ocw.nd.edu/computer-applications/applied-multimedia-technology/four-areas-of-multimedia-analysis

CognitiveDesignSolutions. (2003). Principles of Multimedia. http://www.cognitivedesignsolutions.com/Media/MediaPrinciples.htm

Colemere, I. (2010). Imagine! https://prezi.com/secure/615a80e317e6775e0e44a3444ec8ad95693f6ae1/

Daley, E. (2003). Expanding the concept of literacy. EDUCAUSE. (March/April). http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/erm0322.pdf

Donavant, B. (2011). Narrated digital presentations. In King, K. and T. Cox, The Professors’ Guide to Taming Technology. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Duffy, P. (2008). Engaging the YouTube Google-eyed generation: Strategies for using web 2.0 in teaching and learning. E-Journal of E-Learning. 6(2). (April).http://www.ejel.org/volume6/issue2/p119

Eppler, M. (2006). A comparison between concept maps, mind maps, conceptual diagrams, and visual metaphors as complementary tools for knowledge construction and sharing. Information Visualization. 5. http://liquidbriefing.com/twiki/pub/Dev/RefEppler2006/comparison_between_concept_maps_and_other_visualizations.pdf

Frey, B. & Sutton, J. (2010). A model for developing multimedia learning projects. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching . 6(2) (June). https://jolt.merlot.org/vol6no2/frey_0610.pdf

Grasha, T. (2002). Teaching with Style: A Practical Guide to Enhancing Learning by Understanding Teaching and Learning Styles. Alliance Publishers. http://ilte.ius.edu/pdf/teaching_with_style.pdf

Grush, M. (2011). Literacy redefined: What does it mean to be literate in the digital realm? Campus Technology. (January 11). http://campustechnology.imirus.com/Mpowered/book/vcampus11/i1/p58

Guidry, K. & BrckaLorenz, A. (2010). A comparison of student and faculty academic technology use across disciplines. EDUCAUSE Quarterly. 33(3). http://www.educause.edu/EDUCAUSE+Quarterly/EDUCAUSEQuarterlyMagazineVolum/AComparisonofStudentandFaculty/213682

Henry, L. (2010). Windows Live Movie Maker – support woes. LEHSYS http://www.lehsys.com/2010/10/windows-live-movie-maker-2011-support-woes/

Kaufman, P. & Mohan, J. (2009). Video Use in Higher Education: Options for the Future. Intelligent Television. http://library.nyu.edu/about/Video_Use_in_Higher_Education.pdf

King, K. & Cox, T. (2011). Video development and instructional use: Simple and powerful options. In King, K. and T. Cox, The Professors’ Guide to Taming Technology. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Krages, B. (2006). The Photographer's Right. http://www.krages.com/ThePhotographersRight.pdf

Lengler, R. & Eppler, M. (2007a). Towards a periodic table for visualization methods for management. http://www.visual-literacy.org/periodic_table/periodic_table.pdf

Lengler, R. & Eppler, M. (2007b). A periodic table of visualization methods. http://www.visual-literacy.org/periodic_table/periodic_table.html

Lindgren, M. (2010). Teachers’ guide: 200 hundred years that changed the world. http://www.gapminder.org/downloads/200-years/

Matas, M. (2011, April). A next-generation digital book. [Video file]. http://www.ted.com/talks/lang/eng/mike_matas.html

Mayer, R. (2003). The promise of multimedia learning: Using the same instructional design methods across different media. Learning and Instruction. 13. http://projects.ict.usc.edu/dlxxi/materials/Sept2009/Research%20Readings/MayerMediaMethod03.pdf

McGee, P. & Diaz, V. (2007). Wikis and podcasts and blogs! Oh my! What is a faculty member supposed to do? EDUCAUSE Review. (September/October). http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERM0751.pdf

Miller, M. (2009). Integrating online multimedia into college course and classroom. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 5(2) (June). https://jolt.merlot.org/vol5no2/miller_0609.pdf

Miller, M. (2010). Building a serviceable multimedia homepage with iGoogle. http://www.slideshare.net/soconceptual/miller-building-an-rss-multimedia-homepage

Miller, M. (2011c). Types of online video and audio content with examples. http://www.slideshare.net/soconceptual/miller-types-of-online-video-and-audio-content-with-examples

Miller, M. (2011d). Video clip conversion instructions. http://www.slideshare.net/soconceptual/miller-video-clip-conversion-instructions

Nielsen, L. (2009). Let’s stop making students power down at school. The Innovative Educator. (November 22). http://theinnovativeeducator.blogspot.com/2009/11/lets-stop-making-students-power-down-at.html

Novak, J. & Canas, A. (2008). The theory underlying concept maps and how to use them. Technical Report IHMC CmapTools. http://cmap.ihmc.us/Publications/ResearchPapers/TheoryCmaps/TheoryUnderlyingConceptMaps.htm

NPPA. (2011). NPPA Code of Ethics. National Press Photographers Association. http://www.nppa.org/professional_development/business_practices/ethics.html

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon. 9 (2) (October). http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20- 20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Prensky, M. (2005). Engage me or enrage me. EDUCAUSE Review. (September/October). http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/erm0553.pdf

Rosling, H. (2006, February). Hans Rosling shows the best stats you’ve ever seen. [Video file]. http://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_shows_the_best_stats_you_ve_ever_seen.html

Russell, W. (n.d.). Windows Movie Maker tutorials. About.com. http://presentationsoft.about.com/od/moviemaker/a/mov_mak_beg.htm

Savage, T. & Vogel, K. (2009). An Introduction to Digital Multimedia. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. https://books.google.com/books?id=hge68lNNu1AC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_v2_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Schulten, K. (2010). Teaching with infographics: Places to start. The New York Times: The Learning Network. (August 23). http://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/08/23/teaching-with-infographics-places-to-start/

Segel, E. & Heer, J. (2010). Narrative visualization: Telling stories with data. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. (November). http://vis.stanford.edu/files/2010-Narrative-InfoVis.pdf

SERC. (2010). Ideas for teaching with visualizations. On the Cutting Edge. http://serc.carleton.edu/NAGTWorkshops/visualization/teaching.html

Shank, P. (2005). The value of multimedia in learning. Adobe Design Center. http://www.adobe.com/designcenter/thinktank/valuemedia/The_Value_of_Multimedia.pdf

Smith, S. & Caruso, J. (2010). The ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2010. EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research. http://www.educause.edu/ers1006

Snelson, C. (2011). YouTube across the disciplines: A review of the literature. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching . 7(1) (March). https://jolt.merlot.org/vol7no1/snelson_0311.htm

soconceptual. (2011, March 7). Cartoon: A Inman. [Video file]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmXpUZ2wuOI

soconceptual. (2011, June 3). Digital Story: E Johnson. [Video file]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAaRC0Hi-cg

soconceptual. (2010, August 10). Photo Mosaic: J Horner. [Video file]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAjcxIfz2pA

U.S. Code. (2007). Copyright law of the United States and related laws contained in Tıtle 17 of the United States Code . Circular 92. October.

Wynn, J. (2009). Digital sociology: Emergent technologies in the field and the classroom. Sociological Forum. 24 (2):448-456. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2009.01109.x/abstract

Zhao, R. (2011). Teaching invention through YouTube. Computers and Composition. (Fall, 2010-Spring, 2011). http://www.bgsu.edu/cconline/youtube/