|

Introduction

As broadband Internet access becomes more affordable and the advanced

communication technology provides more varied

features ensuring multi-interactive learning

experiences, synchronous instruction– which

previously had not been adopted as often as

asynchronous – is fast becoming an important

communication mode in online learning fields (Shi,

Mishra, Bonk, Tan, & Zhao, 2006) (Synchronous

instruction, or synchronous learning, in this paper,

refers to real-time instruction or learning

occurring entirely online.). However, because of its

newness, research on synchronous learning has not

received significant research attention (Shi et al.,

2006). As a result, the efficacy of synchronous

learning has not been explored satisfactorily to

know how this mode impacts online learning

experiences, what pedagogical strategies are best

suited for different learners and learning contexts,

and what tools provide better support for those

strategies. Synchronous instructional modes and

techniques offer fresh and interesting opportunities

for enhancing learning across age groups and

disciplines that should attract a plethora of

research attention during the coming decade. What is

exciting for educational researchers is that, at

present, we are only at the entry point for such

research.

For successful online instruction, it is vital to use synchronous and

asynchronous modes appropriately and to acquire

skills and practical strategies for such

communication systems. In this study, the

researchers look closely at the instructors’

practices in a synchronous context and address how

individual strategies have influenced group

interaction and processes. In addition, we examine

how the tools were used to support the instructors

and the students as well as the types of support

that seem necessary for better use of synchronous

technology. Also explored are the instructors’

perceived benefits and disadvantages of the

synchronous mode and tools. Based on the findings,

the researchers suggest several instructional

guidelines for effective synchronous instructional

design and delivery. Given the newness of this

field, however, such guidelines are not intended to

be comprehensive or prescriptive. Clearly, much work

remains.

Issues and Solutions on Synchronous Communication

There is mounting evidence that synchronous instruction has a positive

impact on online students’ learning by supporting

the types of elements often found in face-to-face

contexts (Lobel, Neubauer, & Swedburg, 2002; Murphy,

2005; Oren, Mioduser, & Nachmias, 2002; Orvis,

Wisher, Bonk, & Olson, 2002; Rogers, Graham,

Rasmussen, Campbell & Ure (2003); Shi & Morrow,

2006; Veerman, Andriessen, & Kanselaar, 2000; Wang &

Chen, 2007). Orvis et al. (2002) examine synchronous

text chat interactions in military training

sessions. They indicate that online interactions

focusing on problem-solving show a similar pattern

of interaction as found in a corresponding

face-to-face course within the military: on-task

(55%), social (30%), or technology-related (15%). In

that study, the observed synchronous interaction

patterns changed over time. Mechanical interactions

steadily reduced as students acquired skills and

knowledge about technology. On-task related

interactions reached their peak near the middle of

the training time,

whereas students tended to be more involved in

social interactions at the beginning and end of the

six-month training time period. The researchers

argued that clear patterns of collaborative

interaction occurred in a synchronous problem

solving context. They also contended that social

interactions had a positive impact on the group

problem-solving behaviors.

In another study, Lobel et al. (2002) found that online synchronous

interactions in an inquiry based learning context

were parallel in nature, whereas face-to-face

interactions were typically viewed as serial events.

Parallel communication is observed when online

discussion participants post their individual

messages simultaneously with a given time and date

stamp. These researchers indicate that, “[Parallel

communication] enhanced the perceived worth of the

group to be many times the sum of the worth of its

individuals and it is this synergy that made

collaborative learning attractive and effective to

the participants” (Lobel et al., 2002, ¶11). In

addition, they noted that seventy percent of the

discussion participants in the synchronous learning

situation were actively participating in the

discussion within five-minutes of the one-hour

discussion period. The researchers felt that the

high percentage of participation as a form of

parallel communication was perhaps due to the fact

that the online context observed (in this case,

mediated by the “eClassroom”) was more dynamic in

terms of trust formation and data flow than that

seen in a face-to-face section of the same course.

Of the advantages of synchronous interaction, teacher immediacy and

dynamic interaction are highlighted by researchers

as elements benefiting students who work in

different times and locations. These two advantages

are often discussed in conjunction with issues

involved in the synchronous delivery mode. As Nipper

(1989) points out, “The primary aim of implementing

computer conferencing in adult learning is to

overcome the problem of social distance between

learners and teachers, not just geographical

distance” (p. 71).

In an education context, “distance” can be explained using the concept of

“immediacy.” Immediacy refers to verbal and

non-verbal behaviors used by instructors to reduce

psychological distance between students and

instructors (Gorham, 1988). In a traditional

classroom, nonverbal immediacy is perceived as

physical cues such as body position, facial

expressions, smiling, eye contact, and gestures

(Anderson, 1979), whereas verbal immediacy includes

encouraging students to participate, using personal

examples and humor, providing as well as inviting

feedback, and addressing students by name (Gorham,

1988). It is known that both nonverbal and verbal

immediacy influences student motivation and

cognitive and affective learning in a positive

fashion (Christopher, 1990). Particularly, for low

involvement students, instructor immediacy enhances

student attitude change toward the subject matter

because those students consider the instructors’

high immediacy (e.g., friendly and warm

communication style) as a key aspect of high quality

instruction (Booth-Butterfield, Mosher, & Mollish,

1992).

Some efforts have been made by researchers to see

how immediacy works for Web-based contexts in which

nonverbal immediacy behavior is significantly

limited (Arbaugh, 2001; Freitas, Myers, & Avtgis,

1998; Melrose & Bergeron, 2006; Mullen & Tallent-Runnels,

2006). For instance, when the online dialogue is

mediated by written language, both synchronous and

asynchronous interactions are likely to lack verbal

and physical cues. Arbaugh (2001) finds that the

online immediacy behavior of instructors is an

important factor in Web-based MBA courses impacting

on online students’ satisfaction and learning

experiences. In other studies, instructor immediacy

and student immediacy positively influence and

enhance participant mutual understanding, while, at

the same time, creating an overall social climate

which increases interactivity among participants in

online discussions (Melrose & Bergeron, 2006).

On the other hand, some researchers have expressed concerns or are openly

hesitant about available synchronous tools and

choice options. For instance, Marjanonic (1999, p.

131) stated that “…the majority of synchronous

collaborative tools enable communication (such as

text-based chat systems or video teleconferencing)

rather than computer-mediated collaboration.”

Perhaps it is partly for this reason, communication

over collaboration, that educators have been

somewhat reticent to adopt synchronous instruction

within online courses in higher education where

collaboration is playing an increasing role. Pfister

and Mühlpfordt (2002, pp. 4), citing the work of

Hesse, Garsoffky, and Hron (1997), delineate several

possible limitations in using a synchronous

text-based mode for collaborative discourse: (1)

Lack of social awareness, (2) Insufficient group

coordination, and (3) Deficient coherence of

contributions.

Several solutions are suggested to decrease the potential problems

related to distance discourse and processes. Bonk

and Reynolds (1997) delineate online strategies to

support critical thinking, creative thinking, and

collaborative learning. Focusing on effective

discussion methods, they suggest different roles

assigned to each discussion participant such as a

starter who reads ahead commences discussion, a

wrapper who summarizes the discussion tha interactions and resulting learning outcomes.

Even with such innovative pedagogies, it is difficult to equalize

participate contributions in a synchronous forum.

Pfister and Mühlpfordt (2002), in fact, point out

the problems in equalizing contributions and

creating coherent communication within synchronous

discourse since there can be deficiencies in its

structure. These researchers advocate the use of

learning protocols to facilitate a synchronous

text-based discussion performed by a small group

(e.g., three to five students). That is, the

programmed software provides the necessary

structures of discussions to elicit balanced

contributions and maintain coherence within the

discourse presented by team members. However, the

researchers noted that the learning protocols

introduced in their study may not apply to all

learning contents and contexts. Rather, they

recommended the application for “a kind of short

time exercise with clearly defined objectives and

time restrictions” (Pfister & Mühlpfordt, 2002, ppg.

34). The point the researchers call attention to is

the provision of the proper learning structure for

different learners, contexts, and contents to

maintain the quality of the synchronous discourse.

Research Context

This study has been conducted as a part of a larger research project on

synchronous technology integration into a graduate

distance program in educational technology at a

large state university. The researchers examined a

key course in this program for master’s and doctoral

level students. The students in this course learned

the principles of message and media design and

expanded their learning by developing their own

instructional media products. During the spring of

2006, this course merged students in the distance

and the residential sections. This merger was most

apparent when using a synchronous conferencing tool

called Breeze (now

called Adobe Connect Professional)

for various course activities and meetings.

Twenty-two of the distance students and eleven of

the residential students enrolled in this blended

course. One full-time faculty member and five

graduate teaching assistants jointly facilitated the

course.

During the semester, the students were required to

complete three main projects individually. At the

same time, they were supposed to participate in four

synchronous critique sessions in which students and

instructors met as a small group and conducted peer

evaluations of the students’ ongoing media design

products. The critique sessions held in this

particular course aimed: (1) to help students apply

the newly learned design principles in order to

formatively evaluate media design products, and (2)

to exchange constructive feedback on each other’s

projects in progress.

Each critique session consisted of three to four

students and one instructor as a facilitator. The

session was mediated by combined synchronous

communication technologies, such as the Breeze

web-based collaboration tool, including a text-based

chat or voice conference feature, or a standard

telephone conferencing tool depending on the

instructional conditions and instructor preferences.

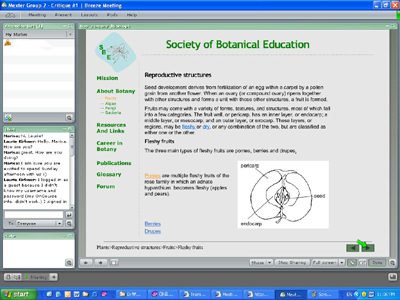

Breeze is a recently emerging Web-based

collaboration system that can connect instructors

and a group of students virtually as well as support

environments for multi-media presentations and

collaborations (Figure 1)

Figure 1. A synchronous critique session in Breeze

context

For each session, the individual instructor

contacted the students (3-4 students per session) to

schedule a meeting. Once the meeting time was set,

the instructor created the virtual meeting space in

the Breeze web server supported by the university

and sent the students the URL of the website that

the students would log into later. On the scheduled

date and time, the instructor coordinated the Breeze

environment in which the student (i.e., the

presenter) uploaded a presentation file to the

Breeze screen to share it with the team members

during the presentation. The instructor also

arranged a Breeze Voice conference or a telephone

conference to communicate with the participants.

Throughout the semester, a total of 49 synchronous

critique sessions were conducted in this course (see

Table 1).

Table 1.Numbers of Synchronous Critique Sessions

and Tools Used

|

Number of synchronous

Critique sessions held |

Tools used for synchronous critique sessions |

|

49

(including 3 practice sessions) |

Breeze* & telephone (38)**

Breeze & Breeze voice chat (4)

Breeze & Breeze text chat (5)

Breeze & Breeze voice chat & telephone (2) |

*

Breeze used as a visual display for uploading

student’s projects and

helping to share the same screen during the

presentation.

** Numbers in parentheses denote the number of

critique sessions

via the various communication tools.

Research Methods

Data were collected from January to May, 2006. The primary data

collection methods included individual interviews

with the instructors as well as the experiences of

one of the researchers who participated in

team-teaching this course. During the semester, this

individual facilitated eight critique sessions as

well as observed two text-based chats and four

recorded critique meetings in the Breeze server. The

researcher’s experiences in this course influenced

the initial list of questions for the interviews as

well as analyses of the data collected. In terms of

the data, the students’ experiences in this study

(Park & Bonk, in press), a course evaluation survey,

the course instructors’ critique assessment reports,

and asynchronous discussions that occurred in the

course website were utilized to interpret the data

collected and uncover any differences between the

instructors’ comments and other data sources.

The interviews aimed to know how instructors experienced the synchronous

critique including their perceptions about

synchronous teaching, the strategies employed, and

the challenges facing participants within a

synchronous context. The subjects participating in

the interviews consisted of one primary faculty

instructor and four assistant instructors who were

involved in teaching this blended course and

facilitating the synchronous critique sessions.

The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured way through

face-to-face meetings or via telephone.

Before each interview, the researcher sent the

instructors the list of the questions (see Appendix)

and information about the study. During the

interview meeting, the researcher used the same

questions in the list as well as follow-up questions

about emerging issues. The meeting time for each

subject took from forty to seventy minutes. All

interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed, and

analyzed by one of the researchers. After each

interview, a summary of the interview was emailed to

each subject to correct the researcher’s

misinterpretations about their intentions and to ask

additional questions to clarify the responses that

they had already made.

Findings and Discussions

In terms of learning effectiveness and satisfaction measured by the

students’ and instructors’ feedback, the synchronous

mode of instruction in this course was successfully

implemented. A course evaluation was conducted

online at the end of the semester. Seven out of

eleven residential students and nineteen out of

twenty-two distance students participated in the

survey. The results revealed that 85 percent of the

residential respondents and 84 percent of the

distance respondents agreed that the online

critiques were helpful for their project completion.

Follow-up interviews with four distance students and

four residential students were then conducted (Park

& Bonk, in press). The findings of the interviews

with the students indicated that they were satisfied

with the synchronous activities in terms of the

prompt feedback, meaningful interactions, and

instructor’s appropriate supports. On the other

hand, time constraints, a lack of reflection time,

tool-related problems, and peers’ insufficient

preparation in the necessary equipment and

technology were identified as the main challenges.

In this study, the collected data from the interviews with instructors

were analyzed to find the common themes as the unit

of analysis. The themes helped the researchers

identify the instructional strategies used for the

synchronous critiques and understand the positive

and negative aspects of the synchronous instruction.

The following section describes the findings in this

study in

terms of the: (1) instructors’ perceived benefits

and issues of the synchronous critique; (2)

instructional supports the instructors provided; and

(3) prevailing issues related to the synchronous

tools used.

Benefits and Issues of Synchronous Instructional

Mode

Compared to the time delayed interaction (e.g.,

discussion forum, Q&A forum), the synchronous

critique discussion used in this course offered

vastly different benefits for the instructors and

the students. The instructors interviewed indicated

that real-time communication helped to promote more

interactive and meaningful engagement during the

discussions. For example, early in the semester

prior to the start of the synchronous critique

meetings, the distance students communicated with

the residential students and the instructors in the

asynchronous forums within the course website. As

the quote below indicates, one of the distance

students felt more connected to other students

during their online collaborations within the

asynchronous conferencing.

The group work was challenging [in the other

course]…but it also helped me to feel connected, and

like I was on the same page as at least a few other

people = ). I'm looking forward to some chats so I

can feel connected again. [Emoticon in original]

Her posting was echoed by several replies from peer

students who essentially expressed the same concerns

and expectations. It is important to note that, even

early in the semester, the students were actually

involved in certain types of interactions in the

asynchronous forum through Q&A sessions and informal

discussions and socializing. Interestingly, the

types of interactions the students appreciated here

were actually more geared to real-time based

engagements, such as synchronous task-oriented

discussions or collaborative team tasks. In fact,

the instructors noted that the student complaints

about feelings of isolation completely disappeared

when they started participating in the synchronous

meetings. However, the opportunity for live

interaction was not the only factor that lowered or

eliminated any deemed isolation barriers. Instead,

several elements might interact to create a sense of

community among the students and stimulate

meaningful interactions. These elements include the

availability of fast feedback, social supports, rich

verbal elements, and instructional strategies.

One of the disadvantages online students commonly experience is delayed

feedback, especially when interactions mainly occur

asynchronously (Doherty, 2006; Song et al., 2004).

Students are often frustrated when their questions

are left unanswered for several days and feedback on

assignments lags. The

instructors in this study reported that the

synchronous interaction

made it possible to

instantly address students’ questions related to the

course content, project requirements, and technology

(e.g., the use of different design software). In

addition, the instructors commented that synchronous interaction within this class encouraged

the critique participants to exchange constructive

feedback, offer voluntary help to team members, and

seek other forms of help from instructors.

For instance, one instructor stated:

It is consistently happening to students [in an

asynchronous forum]. Many of them don’t know what

they have to [say] and they are insecure in being

able to discuss the topic. They are very cautious;

conservative in the amount of what they say or what

they try to address. [However] synchronously,

especially with voice, they go faster and they try

things out little more.

The instructor pointed out that some of the students

in this course who were already involved

professionally in media design fields had a good

chance to contribute to the learning of others. As

an example of the value of incorporating real world

experiences into the class, the instructor

commented, “In this blended course, the residential

students probably benefit from seeing the work of

the distance students because many of them are

employed professionally now and just gave them [the

residential students] a wider group to interact

with.” Other instructors also indicated that the

multiple critique sessions allocated across the

semester helped students significantly improve their

own products.

Unlike face-to-face conversations, the lack of audio

elements in online conversation influences

communications. For example, a text-based chat is

known to be more difficult for effectively

delivering a speaker’s meaning and intentions than a

voice or video chat. According to Dennen (2005),

“Communicating online requires that the writer

choost-size: 10.0pt; font-family: Arial">

The audio-based communication during the critique

discussion in this study supplied rich verbal

elements that a text-based communication could not

offer. The participants were able to communicate by

listening to each others’ voices as well as their

conversational tones and emotional expressions. The

instructors agreed that such verbal cues enhanced

their mutual understanding and increased the general

connectivity among the participants.

While

many students found the verbal communication for online

discussions useful, one of the students interviewed

expressed highly positive experiences, as follows:

“When

you actually hear the voice speaking those same

words there is helpfulness and kindness in the tone.

There is little room for error in the meaning of the

words or critique when you are speaking in real time

and can immediately correct any misconceptions of

your intent.” (Park & Bonk, in press)

In conjunction with verbal communication support

that the instructors pointed out, the words of

encouragement and compliments exchanged during the

critique worked positively for the students who were

worried about their knowledge and skills in media

design. The positive and helpful comments offered by

peers appeared to motivate the students and enhance

their confidence. Consequently, the instructors

argued that this experience could prepare the

students for later criticisms and concerns. In

addition, one of the instructors reported how humor

and verbal immediacy worked for critique climate in

a positive way:

The

critique participants joked around and linked back

to times they have met in other critique sessions.

They talked about the process they had been going

through while working on this project and compared

experiences. They appeared to enjoy and value the

meeting together.

The previous research on immediacy also shed some

light on the influence of the psychological elements

(or immediacy) on online students’ learning and

motivation (Melrose & Bergeron 2006; Mullen &

Tallent-Runnels, 2006).

Instructors’ social supports as well as peer

students’ social presence are influencing elements

not only for enhancing the cognitive learning, but

also for creating a social climate which increases

interactivity among participants in online

discussions (Melrose & Bergeron, 2006). From such

perspectives, establishing

a learning community and facilitating social

supports is important in helping students to be more

active online learners.

Given these findings, the synchronous interaction

opportunities in this study were more likely to play

a positive role in the promotion of interpersonal

and social relationships among participants.

Furthermore, the small-group-based live interaction

could encourage an active role on the part of

learners and promote meaningful collaboration as a

group. Particularly, collaboration mediated by the

audio conferencing tools (e.g., Breeze shared screen

and telephone) could provide a novel social

dimension that was conducive to positive learning

experiences and learning satisfaction. Table 2

presents a summary of the benefits of the

synchronous critique activities.

Table 2. Benefits of Synchronous Peer Critique

Discussion

|

l

Providing immediate feedback

l

Encouraging to exchange multiple perspectives

l

Enhancing dynamic interactions among participants

l

Strengthening social presence

l

Fostering the exchange of emotional supports and supplying verbal

elements |

Instructional Supports

Student positive experiences and satisfaction in

this synchronous discussion could not be achieved

without planned instructional supports and the

appropriate use of communication tools employed by

the course instructors. It has been emphasized by

many other researchers that online instructors’

skills and knowledge in online pedagogy and tools

are critical elements for successful distance

learning (Berge, 1997; Bonk & Dennen, 2003;

Oliver, 2000).

Given such recommendations, the following section

discusses how the course instructors attempted to

take advantage of the benefits of the synchronous

instruction mode and lessen the challenges of the

real-time interaction through various instructional

supports and the available synchronous tools (see

also Table 3). The instructional approaches

presented here are organized based on the strategies

the students viewed useful for their learning. The

two key areas discussed are: (1) Prepare students

before the synchronous activity, and (2) Promote

active student involvement through preplanned

interaction structures, scaffolded learning, and

small group activities.

Prepare Students

Since few of the students in this course had ever used the Breeze

synchronous systems for learning-related purposes

before, there was a pressing need for the

instructors to train the students with the Breeze

system as well as explain the purpose of the

synchronous interaction in this course.

In preparation for the

actual critique discussion sessions, the instructors

used ground rules, practice sessions, and materials

to be analyzed and critiqued.

The ground rules (guidelines) included in the course

syllabus explained the objectives of the critique,

the critique requirements, and the rules and

examples. The guidelines made clear what the

students should do and should not do as a critique

receiver and a critique provider. For example, it

advised that “the person whose work is being

considered will present the work, including a brief

statement of the audience and goals for the work

[and] a brief (2-3 minute) walk-through of the work

that shows as many of its unique characteristics as

possible…” The kinds of statements the critique

givers should include in their verbal critique were

also addressed in terms of discrepancies, concerns,

and successful features.

The rules and guidelines are particularly useful

when they clearly communicate the instructors’

expectations,

the purposes of the critique activity, and

requirements.

The student interviewees responded that they read

the guidelines before the activity and viewed the

information useful not only for the preparation, but

also for understanding of their role in the activity

(Park & Bonk, in press).

Prior to the synchronous critique sessions, practice

sessions were held by the primary instructor via one

face-to-face format and three online synchronous

modes. The practice meetings aimed to demonstrate

the procedures and requirements of the critique and

to accustom students to the functions and features

of Breeze. While the instructor held multiple

practice sessions in varied modes in order to focus

on a different emphasis of the critique activity,

some of the students participating in the interviews

responded that the most helpful session was the

first actual critique meeting because they could

perform it with an authentic topic in the Breeze

environment talking through the audio conferencing

tools. That is, although each practice session was

designed to focus on one or two elements of the

critique activity, it lacked some of the conditions

(i.e., the face-to-face critique meeting focused on

the critique procedures but it could not provide an

opportunity to use the Breeze system). However, both

the instructors’ as well as the students’ points are

worthwhile to include in a plan of practice

sessions. To make practice more useful, it is

necessary that such sessions address individual key

elements of the critique activity under authentic

conditions.

The students preferred that any materials intended

to be used for the synchronous critique meeting be

made available beforehand. For instance, when the

students worked on the development of a Web-based

lesson, some of the instructors collected the

relevant student URLs and distributed the list to

the students in a team ahead of each session. Such a

coordinated approach appeared to work particularly

well because, according to the students, it could

provide them with time to look at each other’s

projects before the critique session began and

assess them against the design principles and

project requirements. Because the synchronous

critique was performed in a time-pressed condition,

the students were often required to perform the

multiple high level and intense cognitive processing

for evaluating other team members’ projects and then

nearly simultaneously discussing them in the context

of course topics. Providing additional review and

reflection time would decrease cognitive overload as

well as increase a chance to bring more quality

feedback to the meeting.

Table 3.

Instructional Strategies Employed by the Instructors

|

Instructional Strategies |

|

Prepare Students

l

Provide ground rules and guidelines.

l

Hold practice sessions.

l

Provide materials to be critiqued prior to the

activity. |

|

Promote an Active Involvement

l

Structure the synchronous critique activity

l

Scaffold students’ discussion

l

Use a small-group and be flexible about

synchronous activity management

l

Require students to keep a critique log and

write a reflection paper after each session. |

Promote Active Involvements

The synchronous critique meeting in this course was

designed from a learner-centered pedagogical

perspective. That is, the instructors encouraged the

learners play a more active role in their learning

by taking the initiative in seeking information and

collaborating with other team members to tackle

issues closely relevant to their professional

interests or course projects.

While the instructors had the freedom to tailor

their own sessions according to the learning context

and the learners assigned to them, the findings of

the study showed that the overall critique sessions

were commonly structured in this manner: (1)

presenters’ presentation, (2) question and answer

between the presenter and team members, (3) team

members’ critique, and (4) summary. Given that

synchronous interactions were held under one-hour

fixed time conditions, the discussion structure was

more likely to help instructors to manage the time

On the other hand, the instructors stated that they

acted as facilitators to give students more power to

freely exchange opinions instead of dominating the

discussion. One instructor, in fact, stated:

While the students were giving their feedback, I

listened to them and considered their opinions to

determine if their feedback is valid or important or

makes sense. When it’s my turn to say, I would

usually say whether I agreed with them and why. I’d

also provide any additional feedback that I think is

important but had been left out by my students.

It was observed that the cognitive supports were

provided during the discussion in varied forms. For

instance, the instructors provided information,

clarified meanings, and summarized key points (e.g.,

“So, to summarize, overall the group liked the

layout and images Jane used on the two pages....Jane

may want to think about whether how many font

treatments she needs, and if there are other ways to

emphasize different types of information.”). The

instructors also brought up questions and issues

whenever the discussion was inactive or the students

focused on one point rather than dealing with

different aspects or perspectives (e.g., “Did

you have a functional reason for choosing these

particular colors?”).

Directing questions to quiet students was a commonly

used strategy in order to draw out

balanced contributions by team members (e.g.,

“Peter, Kim, what do you think about the way Jane

combined the detailed information about fruit with

the information about vegetables on this page?”).

As noted in the quote below, one of the instructors

attempted to validate or acknowledge the critique

providers’ points when they were not confident or

not welcomed by the critique receivers:

When some students have made a very legitimized

criticism but they say, “I am not really sure but it

seems to me…” or “This might be just to me…”, I am

trying to give not only the formal principle, but

also kind of support to their comments.

The students’ responses revealed in the course

evaluations and the interviews indicated that such

instructional supports were particularly valuable to

help them focus and make sure they were successful

in performing their synchronous tasks:

Student A: He [the instructor] effectively

controlled the pace and led us to focus on important

points of our projects. He also came up with

meaningful questions or suggestions about our

projects, which gave me a lot of help.

Students B: A summary at the end by either the

instructor or the participant was helpful. Even

though I had the same remarks noted it was good to

hear the instructor repeat them.

Students C: Her comments were made clearly; they

were constructive with a positive tone, but they

were critical…which you need…I felt like her

insights actually taught me to see slightly

differently.

The instructors agreed that a small group (i.e., 3

students) worked effectively for a one-hour audio

conference. More than three students in a team

created problems in coordinating the sessions and

increasing students’ workload for reviewing the

projects to be critiqued. In contrast, the sessions

tended to be inactive when fewer than three students

were involved in a critique team because of

relatively less diverse experiences and fewer

perspectives. The critique meetings were scheduled to be one hour

sessions. Student attendance at these sessions was

typically not problematic which is not too

surprising given that this was a graduate class. The

same results may not have occurred had this been an

undergraduate class.

Flexible synchronous decision making and guidelines

seem to be vital for deciding the size of the team,

the interval between the critiques, the duration

time, and the scheduling for the given conditions.

In sum, despite the unique advantages of synchronous

mode of interaction, it has often played a

supplementary role within asynchronous online

instruction (e.g., online chats with guest experts

or online office hours). Some researchers (e.g.,

Murphy, 2005) have attributed the low adoption to

its relatively low reliability, high price, and

bandwidth constraints, whereas

other researchers (e.g., Hesse, Garsoffky, & Hron,

1997) have pointed to pedagogical limitations such

as insufficient structure and supports of

synchronous discussion. Several solutions are

suggested to decrease the potential problems related

to real time discourse and processes. Some

researchers such as Pfister and Mühlpfordt (2002)

recommended the use of the necessary structures of

discussions to generate balanced contributions and

maintain coherence within the discourse presented by

team members. It appeared that the instructors in

this study nicely addressed these concerns through

structure and multiple scaffolding strategies to

help

students’ thinking and to guide knowledge

application during the critique activity.

Issues on Synchronous Tools Used

Overall, the instructors showed high satisfaction

with the Breeze shared screen feature. The

advantages of Breeze identified by the instructors

included: (1) Not difficult to share varied file

types visually, (2) Functions to organize critique

participants’ roles and screen control, (3)

Compatibility with the existing course, (4) Ease of

use, and (5) Capability for recording and archiving

Depending on the conditions, the instructors used

the Breeze voice chat or telephone to talk with

their students during the critique. Telephone

conferences were preferred by the instructors over

the Breeze Voice chat because the telephone was an

already familiar tool for the instructors and the

students and it provided a stable condition that was

much less vulnerable to the participants’

technological conditions.

The most frequently encountered problem involved the

resonating voices the Breeze voice tool created.

In

addition,

some students’ connection problems (when it forced

them to drop out repeatedly during the critique)

seriously impacted group communication and the

team’s ultimate performance in a negative direction.

In sum, a useful approach for not depending on any

single software is likely to facilitate more

sophisticated forms of synchronous interaction.

Instructors need to be aware of different

synchronous tools available for their courses and

have knowledge and skills about such tools before

using them in a course. Equally important, the

preparation of necessary equipment, the speed of

synchronous conferencing connections, and the

selection of the appropriate tools must be

considered before holding the synchronous meeting.

Table 4 summarizes the issues discussed.

Table 4. Issues Identified on Synchronous Tools

|

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Breeze shared screen

|

l

Shared view and content during presentation

l

Features to organize participants’ roles and

screen control

l

Compatibility with the existing course

l

Ease of use

l

Recording and archiving function |

Small screen viewer when other pods are used

at the same time.

Delay or difficulty in playing large-sized

files. |

|

Breeze voice conference |

l

No additional cost needed

l

Ease of use |

Vulnerability to user’s technical

conditions |

|

Telephone

conference |

l

Stable condition

l

Ease of use |

Relatively high cost |

|

Breeze text-based chat

|

l

No additional cost required

|

Difficulty in moderating discussions with a

large group of students |

This study examined how the synchronous communication mode was

incorporated in a blended graduate course to

facilitate real-time critique sessions carried out

by the residential and distance students enrolled in

the graduate course. The findings showed that the

combined power of synchronous communication tools

with the effective instructional approaches used for

the synchronous discussion created a novel

instructional condition that could not be easily

achieved by an asynchronous mode of communication.

That is, the real time interaction effectively

supported two of the key instructional goals—effective

learner multimedia presentations and intense learner

critique discussions. The synchronous environment

also fostered

a vast array of social interactions. In addition,

live meetings in small groups encouraged learners to

maintain an active role in the discussions and

facilitated meaningful collaboration. Equally

important, the multiple critique sessions conducted

across the semester provided a recurring chance for

the instructors to

instantly address students’ questions related to the

course. In turn, the non-delayed interaction

benefited the students

by having a chance to exchange useful information among the

students, direct their questions to the instructors,

and improve their projects.

The course evaluation survey and the findings from student interviews

provided evidence that the real time critique

sessions contributed to students’ satisfaction and

overall learning. Coupled with fast-paced live

characteristics of synchronous mode,

several elements such as well designed and effective

instructional approaches, social presence, rich

verbal cues, and proper technology use seemed to

synergistically interact to promote a sense of

community and enhance task-related learning. As

previous studies of asynchronous interaction and

communication have reported (Doherty, 2006; Song et

al., 2004), there were similar complaints about the

lack of interactions and delayed feedback expressed

by some of the distance students early in the

semester before they were involved in the

synchronous meetings. Given that students’

complaints about feelings of isolation disappeared

when the synchronous meetings commenced, the

synchronous critique activity in this course seemed

to address the students’ needs that were not easily

satisfied in the time delayed learning environments.

The team teaching capability in this course appeared

to be one of the critical factors of the synchronous

instruction success witnessed in this study. For

instance, team teaching made it possible to

implement 49 small-group based meetings during the

semester. One primary instructor and five teaching

assistants provided planned supports and practical

guidance for their students to achieve the key

course goals before, during, and after the

synchronous meetings. It is plausible that

recruiting qualified team teaching members and

developing effective synchronous communication and

collaboration aids is the key to successful learning

synchronous learning experiences; at least in higher

education.

It may also be that appropriate use of several

different synchronous tools and approaches played an

important role in fostering quality learning

experiences during this course. The advantages of

real-time communication were multiplied by the use

of combined synchronous tools. The lack of

dependence on a single software tool or approach was

meant to facilitate more sophisticated forms of

synchronous interaction.

Another factor impacting the results found here was that the

students were experienced in educational technology

use. In addition, they were majoring in educational

technology; hence they likely had internal

motivation to succeed here. Both of these factors

might be deemed limitations of this particular

study.

We also observed a potential limitation that the instructors

did not appear to utilize the recorded audio files.

Some of the Breeze meetings were recorded and

archived to allow the students to access the

recorded sound and visual presentation files, while

most of the telephone mediated meetings were

tape-recorded not for the students' use, but for

research purposes. Unfortunately, the researchers

did not have a chance to explore whether or when the

students actually used the Breeze recorded sessions

and how the recorded files actually facilitated

students’ learning in this course. Future studies

might address this issue further.

There were also tool related problems observed in

this study. For instance, we noted severe echoes

generated by audio conference tools, students

sometimes lacking necessary equipments (e.g.,

headsets for talking), and slow network connections,

among other problems and challenges to the

synchronous processes and performances. To cope with

such problems, online instructors might make

different synchronous tools available for their

courses and try to obtain sufficient knowledge and

skills about each of these tools before using them.

Of course, having an instructional team may also

help in this regard, since each team member could

become an expert at a different synchronous tool or

feature.

Implications

Based on the key findings of this study, several suggestions are offered

below related to instructional guidelines for

synchronous teaching. These guidelines include

strategies on how to prepare students for

synchronous audio conference meetings and how to

promote active and meaningful interactions. Our

guidelines and suggestions should help institutions

plan for the incorporation of the synchronous mode

of instruction in their various programs.

Prepare Students for Synchronous Learning

Naturally, the learners are central to the effectiveness of synchronous

online instruction. Learners may not have

experience with technology-mediated synchronous

instruction; at least not with the particular tools

employed within a particular organization. As a

result, it vital to train them with basic technology

skills as well as to explain the purposes and

benefits (as well as the problems) associated with

synchronous communication. Some recommendations are

listed below.

1.

Clarify Technology Requirements. Before

commencing with any synchronous activities or

instruction, require student to be equipped with the

necessary software and equipment (e.g., a headset

for voice chat) as well as a stable Internet

connection. Extensive preparation fosters a more

rich and engaging learning process, including

quality group interactions and performances.

2.

Explain Task Purpose.

Express explicitly what learning outcomes and

behaviors are expected from the synchronous

activity. Course resources and materials,

synchronous interaction guidelines and ground rules,

and team meeting planning aids and worksheets should

be provided to help students’ understanding and

preparation of the synchronous task.

3.

Schedule Practice Sessions. Hold

practice sessions under the same conditions (e.g.,

tools, activities, events, and procedures) as those

implemented during the actual synchronous meetings.

Such practice sessions help students become aware of

the procedures and tasks required in synchronous

activity and to become familiar with the functions

and features of the communication tools.

4.

Be Flexible.

The instructional plan should be flexible enough to

adjust according to students’ emerging needs and

instructional conditions. Decisions made for

communication tools to be used, the duration and

number of synchronous sessions, the number of

participants per session, and the meeting times need

to fit various situations.

Promote Active and Meaningful Interactions

Not only must students be prepared for synchronous instruction, but

instructors need to reconsider their pedagogical

techniques when utilizing synchronous learning

tools. More emphasis should be placed on active and

engaging learning approaches where students are

placed in charge of their own learning. More than

fifteen or twenty minutes of direct instruction

without engaging the learners can prove to be quite

deadly. Utilizing synchronous tools such as online

polling, web browsing, drawing, and chat can involve

students more in the learning process and focus

their attention. Some of the points offered below

also should increase learner motivation and

engagement.

1.

Scaffold Students’ Discussion.

Instructors should not dominate or lecture but

facilitate more interactive and coherent

contributions during the meeting. Instructors, as

subject matter experts, information givers, and

technology advisors, should use various support

strategies such as clarifying meanings,

authenticating students’ points, providing

rationale, and posing questions to keep discussion

active and constructive.

2.

Create a Social Climate.

A positive and friendly

environment helps students to be open and reduces

problems that might hinder students’ participation.

Engaging

students in task-based collaboration is also

important to increase satisfaction and connectivity

among participants. A flexible structure, role

assignment, supportive interaction,

immediate feedback, encouragement, and personal

messages seem to foster a sense of community as well

as accountability among students.

3.

Provide Materials to be Discussed. Topics or

materials to be reviewed during synchronous meetings

should be provided before the meeting.

Unlike asynchronous discussion, a synchronous

meeting requires immediate responses from students often without sufficient time to reflect upon the topics.

Materials given to students assist them not only to

think deeply about the given topics, but also to

bring constructive feedback to the meeting.

4.

Facilitate a Small-Group-Based Discussion.

An audio conference is not suitable for a large

number of participants. Three to four students in a

small group is perhaps the ideal number for quality

synchronous discussions and interactions.

Provide Faculty with Planned Supports.

Many instructors in higher education remain reluctant, resistant, and

reticent to use any form of technology in their

classrooms. Such hesitancy is not surprising given

that new educational technologies seem to emerge

each week with a host of unique expectations for

instructors to consider and potentially find a way

to embed in their classes. Synchronous instructional

tools may pose an even greater challenge and risk

for many instructors. The reason for the sense of

risk is that synchronous instruction--unlike various

supplemental forms of asynchronous instruction such

as online discussion forums, student online blogs

and reflection tasks, and online testing--may

directly replace face-to-face lectures in which they

have invested extensive time and effort and, thus,

are highly passionate about. Professional

development and support in the area of synchronous

teaching and learning, therefore, is crucial.

Without a doubt, adapting synchronous approaches to existing courses

requires new knowledge and skills. Administrators

should understand the different roles and

responsibilities of online instructors and develop

new support systems better suited for their

contexts. To meet these needs, institutional

infrastructure and supports must address issues

related to instructional supports (e.g., pedagogy),

technology supports (e.g., software, hardware,

resources, and skills), and institutional support

(e.g., an incentive program). Several general ideas

are noted below.

1.

Provide Technology Options. Introduce

all the technology tools available to instructors.

They should be given several options for software to

experiment with rather than be assigned a single

software option and forced to fit it to their

instructional approaches and course tasks. And if

the goal is one tool or system, instructors’

evaluations of various tools should be considered

before selection. Higher education institutions

should not simply mandate a tool or system since it

is free or open source. Should such instructor

input be discounted, unnecessary problems and

faculty resistance to the use of the system or tool

will likely arise.

2.

Offer Faculty Professional Development.

Provide faculty members a development program in which

they (1) obtain information about the available

technology tools, (2) share experiences on their

use, and (3) acquire the necessary skills and

knowledge to use a tool or system. The program

should focus on technological skills as well as

pedagogical ones, thereby equipping them with

appropriate approaches for online teaching. The

supports for design, technology, and pedagogy must

be sustained continuously until instructors

gradually become accustomed to effective ways of

teaching with synchronous tools and systems.

3.

We hope that these suggestions will help online instructors

and administrators better plan their synchronous

courses and programs as well as allow future users

to consider the instructional conditions that

synchronous tools and systems offer whenever using

the guidelines. When such events and conditions

occur, perhaps online life will be a bit of a

Breeze!

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elizabeth Boling at Indiana

University for providing continued support and the

sharing of her expertise throughout the process of

this project. We would also like to express our

thanks to all the participants (both instructors and

students) who were willing to share their

experiences and insights with us.

Appendix

Interview Questions for Online Instructors

1.

How many years have you taught online or/and

face-to-face courses?

2.

Did you ever use any synchronous tools for

instructional purposes before this course?

3.

How many synchronous sessions did you hold in

this course? What tools did you use - Breeze voice,

telephone, or text chat?

4.

What instructional value did you see in the

synchronous critique? Did you have any difficulties

in the use of this method?

5.

Before each meeting, did you remind students

to read the critique guidelines included in the

syllabus?

6.

Did you provide critique materials to the

students before the discussion?

7.

What strategies did you use to facilitate

meaningful critique?

8.

How did the Breeze system work for this

synchronous activity?

9.

How often did you use telephone, online voice

chat, or text chat? Tell us about advantages and

disadvantages of each tool. How is Breeze different

from other communication tools you ever used?

10.

What suggestions would you make to improve

the synchronous use?

References

Anderson, J. F. (1979). Teacher immediacy as a

predictor of teaching effectiveness. In D. Nimmo

(Ed.), Communication Yearbook (pp. 543-559).

Thousand Oaks, CA:Sage.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2001), How instructor immediacy

behaviors affect student satisfaction and learning

in web-based courses. Business Communication

Quarterly, 64, 42-54.

Berge, Z.L. (1997). Characteristics of online

teaching in post-secondary, formal education.

Educational Technology, 37(3), 35-47.

Betts, K. (1998). An institutional overview: Factors

influencing faculty participation in distance

education in postsecondary education in the United

States: An institutional study. Online Journal of

Distance Learning Administration, 1 (3).

Retrieved July 29, 2006, from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/betts13.html.

Bonk, C. J., & Dennen, V. (2003).

Frameworks for research, design, benchmarks,

training, and pedagogy in Web-based distance

education. In M. G. Moore & W. Anderson (Eds.),

Handbook of Distance Education (pp. 331-348).

Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bonk, C. J., & Reynolds, T. H. (1997).

Learner-centered Web instruction for higher-order

thinking, teamwork, and apprenticeship. In B. H.

Khan (Eds.), Web-Based Instruction

(pp.167-178). Educational Technology Publications,

Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Booth-Butterfield, S., Mosher, N., & Mollish, D.

(1992). Teacher immediacy and student involvement: A

dual process analysis. Communication Research

Reports, 9, 13-21.

Christopher, D. M. (1990). The relationships among

teacher immediacy behaviors, student motivation, and

learning. Communication Education, 39,

323-340.

Dennen, V. P. (2003). Designing peer feedback

opportunities into online learning experiences.

19th Annual Conference on Distance

Teaching and Learning. Retrieved May 06, 2006,

from

http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/.

Dillon, C. L., & Walsh, S. M. (1992). Faculty: The

neglected resource in distance education. The

American Journal of Distance Education, 6(3),

5-21.

Doherty, W. (2006). An analysis of multiple factors

affecting retention in Web-based community college

courses. Internet and Higher Education. 9,

245-255.

Freitas, A. F., Myers, S. A., & Avtgis, T. A.

(1998).

Students perceptions of instructor immediacy in

conventional and distributed classroom.

Communication Education, 47, 366-372.

Gorham, J. (1988). The relationship between verbal

teacher immediacy behaviors and student learning.

Communication Education, 37, 40-53.

Lobel, M., Neubauer, M., & Swedburg, R. (2002).

Elements of group interaction in a real-time

synchronous online learning-by-doing classroom

without F2F participation. USDLA Journal,

16(4). Retrieved May 06, 2006, from http://www.usdla.org/html/journal/APR02_Issue/article01.html.

Marjanovic, O. (1999). Learning and teaching in a

synchronous collaborative environment. Journal of

Computer Assisted Learning, 14, 129-138.

Melrose, S., & Bergeron, K. (2006). Online graduate

study of health care learners’ perceptions of

instructional immediacy. International Review of

Research in Open and Distance Learning, 7(1).

Retrieved May 07, 2006, from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/255/477

Mullen, G. E., & Tallent-Runnels, M. K. (2006).

Student outcomes and perceptions of instructors’ demands and

support in online and traditional classrooms.

Internet and Higher Education. 9,

257-266.

Murphy, E. (2005). Issues in the adoption of

broadband-enabled learning. British Journal of

Educational Technology, 36(3), 525-536.

Nipper, S. (1989). Third generation distance

learning and computer conferencing. In R. Mason & A.

Kaye (Eds.), Mindweave: Communication, Computers

and Distance Education. Oxford: Pergamon.

Olcott, D. J., & Wright, S. J. (1995). An

institutional support framework for increasing

faculty participation in postsecondary education.

The American Journal of Distance Education, 9(3),

5-17.

Oliver, R. (2000). When teaching meets learning:

design principles and strategies for Web-based

learning environments that support knowledge

construction. In R. Sims, M. O’Reilly & S. Sawkins (Eds).

Learning to choose: Choosing to learn.

Proceedings of the 17th Annual ASCILITE Conference,

17-28.

Oren, A., Mioduser, D., & Nachmias, R. (2002).

The development social climate in virtual learning

discussion groups. International Review of

Research in Open and Distance Learning, 3 (1),

1-19.

Orvis, K. L., Wisher, R. A., Bonk, C. J., & Olson,

T. (2002). Communication patterns during synchronous

Web-based military training in problem solving.

Computers in Human Behavior, 18(6),

783-795.

Park, Y. J., & Bonk, C. J. (in press). Synchronous

learning experiences: Distance and residential

learners’ perspectives in a blended graduate course.

The Journal of Interactive Online Learning.

6(3).

Pfister, H., & Muhlpfordt, M. (2002). Supporting

discourse in a synchronous learning environment: The

learning protocol approach. In G.. Stahl (Ed.)

(2002). Computer support for collaborative

learning: Foundations for a CSCL Community

Proceedings of CSCL2002. Retrieved May 06, 2006,

from http://newmedia.colorado.edu/cscl/178.html

Rogers, P. C., Graham, C. R., Rasmussen, R.,

Campbell, J. O., & Ure, D. M. (2003). Blending

face-to-face and distance learners in a synchronous

class: Instructor and learner experiences. The

Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 4(3),

245-251.

Shi, S., Mishra, P., Bonk, C.J., Tan, S., & Zhao Y.

(2006). Thread theory: A framework applied to

content analysis of synchronous computer mediated

communication data. International Journal of

Instructional Technology & Distance learning. 3

(3). Retrieved December 31, 2006, from

http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Mar_06/article02.htm

Shi, S., & Morrow, B. V. (2006). E-conferencing for

instruction: What works. Educause Quarterly.

29(4). Retrieved February 20, 2007, from http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/eqm0646.pdf

Song, L., Singleton, E. S., Hill, J. R., & Koh, M.

H. (2004). Improving online learning: Student

perceptions of useful and challenging

characteristics. Internet and Higher Education,

7, 59-70.

Veerman, A.L., Andriessen, J.E.B., & Kanselaar, G.

(2000).

Learning through synchronous electronic discussion,

Computers & Education, 34, 269-290.

Wang, Y., & Chen, N. (2007). Online synchronous

language learning: SLMS over the Internet.

Innovate, 3(3). Retrieved February 20,

2007, from http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=337

|